Stony Brook University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

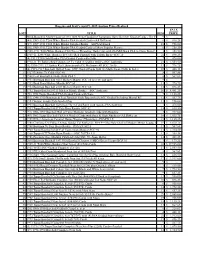

Lot# Title Bids Sale Price 1

Huggins and Scott'sAugust 7, 2014 Auction Prices Realized SALE LOT# TITLE BIDS PRICE 1 Ultimate 1974 Topps Baseball Experience: #1 PSA Graded Master, Traded & Team Checklist Sets with (564) PSA12 10,$ Factory82,950.00 Set, Uncut Sheet & More! [reserve met] 2 1869 Peck & Snyder Cincinnati Red Stockings (Small) Team Card SGC 10—First Baseball Card Ever Produced!22 $ 16,590.00 3 1933 Goudey Baseball #106 Napoleon Lajoie—PSA Authentic 21 $ 13,035.00 4 1908-09 Rose Co. Postcards Walter Johnson SGC 45—First Offered and Only Graded by SGC or PSA! 25 $ 10,072.50 5 1911 T205 Gold Border Kaiser Wilhelm (Cycle Back) “Suffered in 18th Line” Variation—SGC 60 [reserve not met]0 $ - 6 1915 E145 Cracker Jack #30 Ty Cobb PSA 5 22 $ 7,702.50 7 (65) 1909-11 T206 White Border Singles with (40) Graded Including (4) Hall of Famers 16 $ 2,370.00 8 (37) 1909-11 T206 White Border PSA 1-4 Graded Cards with Willis 8 $ 1,125.75 9 (5) 1909-11 T206 White Borders PSA Graded Cards with Mathewson 9 $ 711.00 10 (3) 1911 T205 Gold Borders with Mordecai Brown, Walter Johnson & Cy Young--All SGC Authentic 12 $ 711.00 11 (3) 1909-11 T206 White Border Ty Cobb SGC Authentic Singles--Different Poses 14 $ 1,777.50 12 1909-11 T206 White Borders Walter Johnson (Portrait) & Christy Mathewson (White Cap)--Both SGC Authentic 9 $ 444.38 13 1909-11 T206 White Borders Ty Cobb (Green Portrait) SGC 55 12 $ 3,555.00 14 1909-11 T205 & T206 Hall of Famers with Lajoie, Mathewson & McGraw--All SGC Graded 12 $ 503.63 15 (4) 1887 N284 Buchner Gold Coin SGC 60 Graded Singles 4 $ 770.25 16 (6) -

* Text Features

The Boston Red Sox Wednesday, July 1, 2020 * The Boston Globe College lefties drafted by Red Sox have small sample sizes but big hopes Julian McWilliams There was natural anxiety for players entering this year’s Major League Baseball draft. Their 2020 high school or college seasons had been cut short or canceled because of the COVID-19 pandemic. They lost that chance at increasing their individual stock, and furthermore, the draft had been reduced to just five rounds. Lefthanders Shane Drohan and Jeremy Wu-Yelland felt some of that anxiety. The two were in their junior years of college. Drohan attended Florida State and Wu-Yelland played at the University of Hawaii. There was a chance both could have gone undrafted and thus would have been tasked with the tough decision of signing a free agent deal capped at $20,000 or returning to school for their senior year. “I didn’t know if I was going to get drafted,” Wu-Yelland said in a phone interview. “My agent was kind of telling me that it might happen, it might not. Just be ready for anything.” Said Drohan, “I knew the scouting report on me was I have the stuff to shoot up on draft boards but I haven’t really put it together yet. I felt like I was doing that this year and then once [the season] got shut down, that definitely played into the stress of it, like, ‘Did I show enough?’ ” As it turned out, both players showed enough. The Red Sox selected Wu-Yelland in the fourth round and Drohan in the fifth. -

Toss-Up Questions 1. His Message in the Kind Keeper That Having Mistresses Is a "Crying Shame" Made It Very Badly Received

Toss-up Questions 1. His message in The Kind Keeper that having mistresses is a "crying shame" made it very badly received. His Spanish Fryar attacked both England's ancient enemy and Catholicism and Religio Laici was an exposition of the Protestant creed. His Heroic Stanzas commemorate the death of Oliver Cromwell, while his Astraea Redux celebrates the restoration of Charles II. FTP, name this English poet laureate who is known for Pindaric odes such as Alexander's Feast and for his long poem on the Dutch War, Annus Mirabalis. John Dryden 2. Allowed by Einstein's results, their creation requires only the use of "exotic matter" with negative energy that is thought to arise when quantum fluctuations in vacuum are suppressed. Perhaps appearing spontaneously right now on a . minute scale, Stephen Hawking says they are useless because even a single particle brings their destabilization, but we may be able to peer through them into other universes. FTP, name these theoretical shortcuts from one area of space time to another, one of which is now inhabited by Captain Sisko. Wormholes 3. His odd taste was cultivated by his father, who let him listen only to offbeat compositions that customers didn't want, and he paid tribute to Columbus with 1992's The Voyage. He studied with Milhaud (Mee-yo) and transcribed the music of Ravi Shankar, starting an Indian fascination which led to his Satyagraha. His recent operas include In the Penal Colony, based on the Kafka short story, as well as Galileo Galilei. FTP, name this composer famous for helping to popularize minimalist music with his opera Einstein on the Beach. -

Ba Mss 100 Bl-2966.2001

GUIDE TO THE BOWIE K KUHN COLLECTION National Baseball Hall of Fame Library National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum 25 Main Street Cooperstown, NY 13326 www.baseballhall.org Collection Number BA MSS 100 BL-2966.2001 Title Bowie K Kuhn Collection Inclusive Dates 1932 – 1997 (1969 – 1984 bulk) Extent 48.2 linear feet (109 archival boxes) Repository National Baseball Hall of Fame Library 25 Main Street Cooperstown, NY 13326 Abstract This is a collection of correspondence, meeting minutes, official trips, litigation files, publications, programs, tributes, manuscripts, photographs, audio/video recordings and a scrapbook relating to the tenure of Bowie Kent Kuhn as commissioner of Major League Baseball. Preferred Citation Bowie K Kuhn Collection, BA MSS 100, National Baseball Hall of Fame & Museum, Cooperstown, NY. Provenance This collection was donated to the National Baseball Hall of Fame by Bowie Kuhn in 1997. Kuhn’s system of arrangement and description was maintained. Access By appointment during regular business hours, email [email protected]. Property Rights This National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum owns the property rights to this collection. Copyright For information about permission to reproduce or publish, please contact the library. Processing Information This collection was processed by Claudette Scrafford, Manuscript Archivist and Catherine Mosher, summer student, between June 2010 and February 2012. Biography Bowie Kuhn was the Commissioner of Major League Baseball for three terms from 1969 to 1984. A lawyer by trade, Kuhn oversaw the introduction of free agency, the addition of six clubs, and World Series games played at night. Kuhn was born October 28, 1926, a descendant of famous frontiersman Jim Bowie. -

Major League Baseball and the Antitrust Rules: Where Are We Now???

MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL AND THE ANTITRUST RULES: WHERE ARE WE NOW??? Harvey Gilmore, LL.M, J.D.1 INTRODUCTION This essay will attempt to look into the history of professional baseball’s antitrust exemption, which has forever been a source of controversy between players and owners. This essay will trace the genesis of the exemption, its evolution through the years, and come to the conclusion that the exemption will go on ad infinitum. 1) WHAT EXACTLY IS THE SHERMAN ANTITRUST ACT? The Sherman Antitrust Act, 15 U.S.C.A. sec. 1 (as amended), is a federal statute first passed in 1890. The object of the statute was to level the playing field for all businesses, and oppose the prohibitive economic power concentrated in only a few large corporations at that time. The Act provides the following: Every contract, combination in the form of trust or otherwise, or conspiracy, in restraint of trade or commerce among the several states, or with foreign nations, is declared to be illegal. Every person who shall make any contract or engage in any combination or conspiracy hereby declared to be illegal shall be deemed guilty of a felony…2 It is this statute that has provided a thorn in the side of professional baseball players for over a century. Why is this the case? Because the teams that employ the players are exempt from the provisions of the Sherman Act. 1 Professor of Taxation and Business Law, Monroe College, the Bronx, New York. B.S., 1987, Accounting, Hunter College of the City University of New York; M.S., 1990, Taxation, Long Island University; J.D., 1998 Southern New England School of Law; LL.M., 2005, Touro College Jacob D. -

Ba Mss 121 Bl-587.69 – Bl-593.69

Collection Number BA MSS 121 BL-587.69 – BL-593.69 Title Tom Meany Scorebooks Inclusive Dates 1947 – 1963 NY teams Access By appointment during regular hours, email [email protected]. Abstract These scorebooks have scored games from spring training, All-Star games, and World Series games, and a few regular season games. Volume 1 has Jackie Robinson’s first game, April 15, 1947. Biography Tom Meany was recruited to write for the new Brooklyn edition of the New York Journal in 1922. The following year he earned a byline in the Brooklyn Daily Times as he covered the Dodgers. Over the years, Meany's sports writing career saw stops at numerous papers including the New York Telegram (later the World-Telegram), New York Star, Morning Telegraph, as well as magazines such as PM and Collier's. Following his sports writing career, Meany joined the Yankees in 1958. In 1961 he joined the expansion Mets as publicity director and later served as promotions director before his untimely death in 1964 at the age of 60. He received the Spink Award in 1975. Source: www.baseballhall.org Content List Volume 1 BL-587.69 1947 - Spring training, season games April 15, Jackie Robinson’s first game World Series - Dodgers v. Yankees 1948 - Spring training Volume 2 BL-588.69 1948 – Season games World Series, Indians vs. Braves 1962 - World Series, Giants vs. Yankees Volume 3 BL-589.69 1949 -Spring training, season games 1950 - May, Jul 11 All-Star game World Series, Yankees vs. Phillies 1951 - Playoff games, Dodgers vs. Giants World Series, Giants vs. -

Postseaason Sta Rec Ats & Caps & Re S, Li Ecord Ne S Ds

Postseason Recaps, Line Scores, Stats & Records World Champions 1955 World Champions For the Brooklyn Dodgers, the 1955 World Series was not just a chance to win a championship, but an opportunity to avenge five previous World Series failures at the hands of their chief rivals, the New York Yankees. Even with their ace Don Newcombe on the mound, the Dodgers seemed to be doomed from the start, as three Yankee home runs set back Newcombe and the rest of the team in their opening 6-5 loss. Game 2 had the same result, as New York's southpaw Tommy Byrne held Brooklyn to five hits in a 4-2 victory. With the Series heading back to Brooklyn, Johnny Podres was given the start for Game 3. The Dodger lefty stymied the Yankees' offense over the first seven innings by allowing one run on four hits en route to an 8-3 victory. Podres gave the Dodger faithful a hint as to what lay ahead in the series with his complete-game, six-strikeout performance. Game 4 at Ebbets Field turned out to be an all-out slugfest. After falling behind early, 3-1, the Dodgers used the long ball to knot up the series. Future Hall of Famers Roy Campanella and Duke Snider each homered and Gil Hodges collected three of the club’s 14 hits, including a home run in the 8-5 triumph. Snider's third and fourth home runs of the Series provided the support needed for rookie Roger Craig and the Dodgers took Game 5 by a score of 5-3. -

PIIIII-IIIIIPI Covers Less Area • Nelli

ALL-CITY Caddies to Be Scarce Again DITROIT SUNDAY TUNIS C April 15, 1945—1, Page 3 Sparing Firing Line' THE GREATER GAME By Edgar Hayes ¦p „ ? ????? y * ... riHtf-• PLEA: LIGHT BAGS FOR LIGHT BOYS Set for Shoot Times Sports Writer No Pins By M. F. DRUKENBROD 'Dotte Hi' Leads Caddie superintendents and golf Awarded Silver Star Three E&B Bowlers pros are agreed there'll be no relief in the caddie situation here Hearst Entries ) on All-City Team this season. Lt. Sheldon Moyer, who wrote Michigan State sports for time, there won’t Until vacation By GILLIES The Detroit Times for four years, has been awarded the Silver to DON be enough boys go around and Star for heroism in action, it was learned in a letter from Georgt By HAROLD KAHL even then, not enough for week- Bullets will whiz south instead x. wf ends and special occasions. of north when more than 3,000 Maskin, another Times sports writer w’ho is in London. League and tournament play JOE NORRIS This means doubling up, two shooters fire their matches in the Lt. Moyer was honored for his part in saving a lot of equip- were the prime requisites in the bags for one boy, a problem in (Stroh) fifth annual llearst-Times tourna- ment for an armored division the Germans had started to shell. itself, the caddies again Wg¥ \ \ selection of the top 25 bowlers in because .aHSU-'---¦¦¦ J V Moyer was wounded in the action but has completely recovered. be and younger than ment at Olympia, April 28 and 29. -

2016 National League Championship Series - Game 6 Los Angeles Dodgers Vs

2016 NATIONAL LEAGUE CHAMPIONSHIP SERIES - GAME 6 LOS ANGELES DODGERS VS. CHICAGO CUBS Saturday, October 22 - 7:08 p.m. (CDT) - Wrigley Field, Chicago, IL LHP Clayton Kershaw (2-0, 3.72) vs. RHP Kyle Hendricks (0-1, 3.00) FS1 - ESPN Radio GAME SIX: The Cubs head into Game 6 with a 3-2 series lead. Teams up 3-2 in best-of-seven LCS play are 27-10 all-time, and 16-4 when the final two games are at home. Chicago is 6-9 all-time in postseason games with a chance to clinch a series, but 0-6 in that scenario in the NLCS. The Dodgers are 16-23 all-time in postseason games in which they face elimi- nation. The Cubs won Game 5 on Thursday in Los Angeles; of the 52 previous LCS series that have gone to five games, the winner of Game 5 is 34-18. - Elias Sports Bureau LIVE ARM: Clayton Kershaw had six strikeouts in Game 2 on Sunday, giving him 102 career postseason strikeouts. He enters tonight's start ranking third among active players, behind Justin Verlander (112) and John Lackey (106). WE HAVE A HEART BEAT: After batting just 2x32 (.063) with four RBI over the first three games of the NLCS, the Cubs 3-4-5 hitters are batting .440 (11x25) with three doubles, a home run (Anthony Rizzo) and eight RBI over the last two games. UPS AND DOWNS: The Cubs have scored 26 runs in this series despite being shut out twice in five games. -

Landis, Cobb, and the Baseball Hero Ethos, 1917 – 1947

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2020 Reconstructing baseball's image: Landis, Cobb, and the baseball hero ethos, 1917 – 1947 Lindsay John Bell Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Recommended Citation Bell, Lindsay John, "Reconstructing baseball's image: Landis, Cobb, and the baseball hero ethos, 1917 – 1947" (2020). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 18066. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/18066 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Reconstructing baseball’s image: Landis, Cobb, and the baseball hero ethos, 1917 – 1947 by Lindsay John Bell A dissertation submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Major: Rural Agricultural Technology and Environmental History Program of Study Committee: Lawrence T. McDonnell, Major Professor James T. Andrews Bonar Hernández Kathleen Hilliard Amy Rutenberg The student author, whose presentation of the scholarship herein was approved by the program of study committee, is solely responsible for the content of this dissertation. The Graduate College will ensure this dissertation is globally accessible and will not permit alterations after a degree is conferred. Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2020 Copyright © Lindsay John Bell, 2020. All rights reserved. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ............................................................................................................. iii ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................................... vi CHAPTER 1. -

Official Game Information

Official Game Information Yankee Stadium • One East 161st Street • Bronx, NY 10451 Media Relations Phone: (718) 579-4460 • [email protected] • Twitter: @yankeespr YANKEES BY THE NUMBERS NOTE 2012 (Postseason) 2012 AMERICAN LEAGUE CHAMPIONSHIP SERIES – GAME 1 Home Record: . 51-30 (2-1) NEW YORK YANKEES (3-2/95-67) vs. DETROIT TIGERS (3-2/88-74) Road Record: . 44-37 (1-1) Day Record: . .. 32-20 (---) LHP ANDY PETTITTE (0-1, 3.86) VS. RHP DOUG FISTER (0-0, 2.57) Night Record: . 63-47 (3-2) Saturday, OctOber 13 • 8:07 p.m. et • tbS • yankee Stadium vs . AL East . 41-31 (3-2) vs . AL Central . 21-16 (---) vs . AL West . 20-15 (---) AT A GLANCE: The Yankees will play Game 1 of the 2012 American League Championship Series vs . the Detroit Tigers tonight at Yankee Stadium…marks the Yankees’ 15th ALCS YANKEES IN THE ALCS vs . National League . 13-5 (---) (Home Games in Bold) vs . RH starters . 58-43 (3-0) all-time, going 11-3 in the series, including a 7-2 mark in their last nine since 1996 – which vs . LH starters . 37-24 (0-2) have been a “best of seven” format…is their third ALCS in five years under Joe Girardi (also YEAR OPP W L Detail Yankees Score First: . 59-27 (2-1) 2009 and ‘10)…are 34-14 in 48 “best-of-seven” series all time . 1976** . KC . 3 . 2 . WLWLW Opp . Score First: . 36-40 (1-1) This series is a rematch of the 2011 ALDS, which the Tigers won in five games . -

PDF of Apr 15 Results

Huggins and Scott's April 9, 2015 Auction Prices Realized SALE LOT# TITLE BIDS PRICE 1 Mind-Boggling Mother Lode of (16) 1888 N162 Goodwin Champions Harry Beecher Graded Cards - The First Football9 $ Card - in History! [reserve not met] 2 (45) 1909-1911 T206 White Border PSA Graded Cards—All Different 6 $ 896.25 3 (17) 1909-1911 T206 White Border Tougher Backs—All PSA Graded 16 $ 956.00 4 (10) 1909-1911 T206 White Border PSA Graded Cards of More Popular Players 6 $ 358.50 5 1909-1911 T206 White Borders Hal Chase (Throwing, Dark Cap) with Old Mill Back PSA 6--None Better! 3 $ 358.50 6 1909-11 T206 White Borders Ty Cobb (Red Portrait) with Tolstoi Back--SGC 10 21 $ 896.25 7 (4) 1911 T205 Gold Border PSA Graded Cards with Cobb 7 $ 478.00 8 1910-11 T3 Turkey Red Cabinets #9 Ty Cobb (Checklist Offer)--SGC Authentic 21 $ 1,553.50 9 (4) 1910-1911 T3 Turkey Red Cabinets with #26 McGraw--All SGC 20-30 11 $ 776.75 10 (4) 1919-1927 Baseball Hall of Fame SGC Graded Cards with (2) Mathewson, Cobb & Sisler 10 $ 448.13 11 1927 Exhibits Ty Cobb SGC 40 8 $ 507.88 12 1948 Leaf Baseball #3 Babe Ruth PSA 2 8 $ 567.63 13 1951 Bowman Baseball #253 Mickey Mantle SGC 10 [reserve not met] 9 $ - 14 1952 Berk Ross Mickey Mantle SGC 60 11 $ 776.75 15 1952 Bowman Baseball #101 Mickey Mantle SGC 60 12 $ 896.25 16 1952 Topps Baseball #311 Mickey Mantle Rookie—SGC Authentic 10 $ 4,481.25 17 (76) 1952 Topps Baseball PSA Graded Cards with Stars 7 $ 1,135.25 18 (95) 1948-1950 Bowman & Leaf Baseball Grab Bag with (8) SGC Graded Including Musial RC 12 $ 537.75 19 1954 Wilson Franks PSA-Graded Pair 11 $ 956.00 20 1955 Bowman Baseball Salesman Three-Card Panel with Aaron--PSA Authentic 7 $ 478.00 21 1963 Topps Baseball #537 Pete Rose Rookie SGC 82 15 $ 836.50 22 (23) 1906-1999 Baseball Hall of Fame Manager Graded Cards with Huggins 3 $ 717.00 23 (49) 1962 Topps Baseball PSA 6-8 Graded Cards with Stars & High Numbers--All Different 16 $ 1,015.75 24 1909 E90-1 American Caramel Honus Wagner (Throwing) - PSA FR 1.5 21 $ 1,135.25 25 1980 Charlotte O’s Police Orange Border Cal Ripken Jr.