Rap As a Reflection of Reality for Inner City Youth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Virtuoso, Beatdown

Virtuoso, Beatdown (Virtuoso) Yo, I be attestin' bad you soon discover I'm the best around Virtuoso omnipotent medulla rule the extra crowds Step in battles weapon-rals give ya chest a pound 'til ya breast is ground meat Pharaohs Army sound fleet Snatch ahold of half ya soul make, casserole Crack a pole on ya back and roll you in the blackest hole The winter brewed, enter nude Amazonian jungle warfare Silver back guerilla I'm covered in more hair than four chairs in a barber shop Vocals hard as rocks and the beat's on smash Make ya veto, jigga weak foe Cause my machete unique flow fuckin' beat yo ass I got the key to sense or hear a deer sharp as fox Sound as when carver chop, galaxies and stars'll drop You know Virt, run with ogres who throw dirt Stomp ya ass 'til ya bones squirt like yogurt (T-Ruckus) Aiyyo rush extreme pervert, I'm undercover covert You need to put in work, and get ya games out my face Let the flames in the place, you fuckin' wid Ruck's a fatal move You stand in disgrace yo my brain's in outerspace Taste the toxic, improved reflexes like shadowboxin' Sternum crack, extreme force applied to ya back Pick ya torture that's the rack I'll scortch ya with the lift And word style I clash like, (woof) with full clips Guerilla war I killed ya core Atilla the Hun don't want none I rap shit, into the floors Spittin' shots through ya door, and kick that bitch down From the bowel, where Ruck throws the mic to the ground In discussin' Ruck you trust, word to us You spittin' the shit we flush time to bust And crack the earth's crust -

EXTENSIONS of REMARKS December 4, 1973 Port on S

39546 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS December 4, 1973 port on S. 1443, the foreign aid author ADJOURNMENT TO 11 A.M. Joseph J. Jova, of Florida, a Foreign Serv ization bill. ice officer of the class of career minister, to Mr. ROBERT C. BYRD. Mr. Presi be Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipo There is a time limitaiton thereon. dent, if there be no further business to tentiary of the United States of America to There will be at least one yea-and-nay come before the Senate, I move, in ac Mexico. vote, I am sure, on the adoption of the cordance with the previous order, that Ralph J. McGuire, of the District of Colum. bia, a Foreign Service officer of class 1, to be conference report, and there may be the Senate stand in adjournment until Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipoten other votes. the hour of 11 o'clock a.m. tomorrow. t iary cf the United States of America to the On the disposition of the conference The motion was agreed to; and at 6: 45 Republic of Mali. report on the foreign aid authorization p.m., the Senate adjourned until tomor Anthony D. Marshall, of New York, to be row, Wednesday, December 5, 1973, at Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipoten bill, S. 1443, the Senate will take up tiary of the United States of America to the Calendar Order No. 567, S. 1283, the so lla.m. Republic of Kenya. called energy research and development Francis E. Meloy, Jr., of the District of bill. I am sure there will be yea and Columbia, a Foreign Service officer of the NOMINATIONS class of career minister, to be Amb1ssador nay votes on amendments thereto to Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of the morrow. -

I Make This Pledge to You Alone, the Castle Walls Protect Our Back That I Shall Serve Your Royal Throne

AMERA M. ANDERSEN Battlefield of Life “I make this pledge to you alone, The castle walls protect our back that I shall serve your royal throne. and Bishops plan for their attack; My silver sword, I gladly wield. a master plan that is concealed. Squares eight times eight the battlefield. Squares eight times eight the battlefield. With knights upon their mighty steed For chess is but a game of life the front line pawns have vowed to bleed and I your Queen, a loving wife and neither Queen shall ever yield. shall guard my liege and raise my shield Squares eight times eight the battlefield. Squares eight time eight the battlefield.” Apathy Checkmate I set my moves up strategically, enemy kings are taken easily Knights move four spaces, in place of bishops east of me Communicate with pawns on a telepathic frequency Smash knights with mics in militant mental fights, it seems to be An everlasting battle on the 64-block geometric metal battlefield The sword of my rook, will shatter your feeble battle shield I witness a bishop that’ll wield his mystic sword And slaughter every player who inhabits my chessboard Knight to Queen’s three, I slice through MCs Seize the rook’s towers and the bishop’s ministries VISWANATHAN ANAND “Confidence is very important—even pretending to be confident. If you make a mistake but do not let your opponent see what you are thinking, then he may overlook the mistake.” Public Enemy Rebel Without A Pause No matter what the name we’re all the same Pieces in one big chess game GERALD ABRAHAMS “One way of looking at chess development is to regard it as a fight for freedom. -

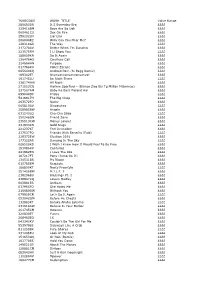

Chart: Top50 AUDIO URBAN

Chart: Top50_AUDIO_URBAN Report Date (TW): 2012-11-18 --- Previous Report Date(LW): 2012-11-11 TW LW TITLE ARTIST GENRE RECORD LABEL 1 1 Ball (clean) T.i. Ft Lil Wayne Hip Hop Grand Hustle Records / Atlantic 2 3 Poetic Justice (dirty) Kendrick Lamar Ft Drake Hip Hop Interscope Records 3 2 Ball (dirty) T.i. Ft Lil Wayne Hip Hop Grand Hustle Records / Atlantic 4 4 Ball (instrumental) T.i. Ft Lil Wayne Hip Hop Grand Hustle Records / Atlantic 5 6 Adorn (dj Tedsmooth Remix) Miguel Ft Diddy & French Montana Hip Hop RCA Records 6 5 911 (clean) Rick Ross Ft 2 Chainz Hip Hop MayBach Music 7 7 Adorn (dj Tedsmooth Remix) (clean) Miguel Ft Puff Daddy And French Montana R&b RCA Records 8 8 Birthday Song Remix (clean) 2 Chainz Ft Diddy & Rick Ross Hip Hop Island Def Jam Records 9 13 Poetic Justice (clean) Kendrick Lamar Ft Drake Hip Hop Interscope Records 10 15 F_ckin Problems (dirty) Asap Rocky Ft Drake, 2 Chainz And Kendrick LamarHip Hop RCA Records 11 9 911 (dirty) Rick Ross Ft 2 Chainz Hip Hop MayBach Music 12 10 Birthday Song Remix (dirty) 2 Chainz Ft Diddy & Rick Ross Hip Hop Island Def Jam Records 13 11 Believe It (dirty) Meek Mill Ft Rick Ross Hip Hop Maybach Music Group 14 12 Dont Make Em Like You (clean) Neyo Ft Wiz Khalifa R&b Island Def Jam Records 15 17 Get Right (clean) Young Jeezy Hip Hop Island Def Jam Records 16 18 Bands A Make Her Dance (dirty) Trey Songz Hip Hop Atlantic Records 17 20 Dump Truck (clean) E 40 And Too Short Ft Travis Porter Hip Hop Sick Wit It Records 18 32 Guap (dirty) Big Sean Hip Hop island Def Jam Records 19 30 Poetic Justice (instrumental) Kendrick Lamar Ft Drake Hip Hop Interscope Records 20 22 Bandz A Make Her Dance (instrumental) Juicy J Ft Lil Wayne And 2 Chainz Hip Hop Hypnotize Minds 21 21 Compton (dirty) Kendrick Lamar Ft Dr. -

Hip-Hop's Diversity and Misperceptions

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Honors College Summer 8-2020 Hip-Hop's Diversity and Misperceptions Andrew Cashman Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors Part of the Music Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HIP-HOP’S DIVERSITY AND MISPERCEPTIONS by Andrew Cashman A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for a Degree with Honors (Anthropology) The Honors College University of Maine August 2020 Advisory Committee: Joline Blais, Associate Professor of New Media, Advisor Kreg Ettenger, Associate Professor of Anthropology Christine Beitl, Associate Professor of Anthropology Sharon Tisher, Lecturer, School of Economics and Honors Stuart Marrs, Professor of Music 2020 Andrew Cashman All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT The misperception that hip-hop is a single entity that glorifies wealth and the selling of drugs, and promotes misogynistic attitudes towards women, as well as advocating gang violence is one that supports a mainstream perspective towards the marginalized.1 The prevalence of drug dealing and drug use is not a picture of inherent actions of members in the hip-hop community, but a reflection of economic opportunities that those in poverty see as a means towards living well. Some artists may glorify that, but other artists either decry it or offer it as a tragic reality. In hip-hop trends build off of music and music builds off of trends in a cyclical manner. -

ANSAMBL ( [email protected] ) Umelec

ANSAMBL (http://ansambl1.szm.sk; [email protected] ) Umelec Názov veľkosť v MB Kód Por.č. BETTER THAN EZRA Greatest Hits (2005) 42 OGG 841 CURTIS MAYFIELD Move On Up_The Gentleman Of Soul (2005) 32 OGG 841 DISHWALLA Dishwalla (2005) 32 OGG 841 K YOUNG Learn How To Love (2005) 36 WMA 841 VARIOUS ARTISTS Dance Charts 3 (2005) 38 OGG 841 VARIOUS ARTISTS Das Beste Aus 25 Jahren Popmusik (2CD 2005) 121 VBR 841 VARIOUS ARTISTS For DJs Only 2005 (2CD 2005) 178 CBR 841 VARIOUS ARTISTS Grammy Nominees 2005 (2005) 38 WMA 841 VARIOUS ARTISTS Playboy - The Mansion (2005) 74 CBR 841 VANILLA NINJA Blue Tattoo (2005) 76 VBR 841 WILL PRESTON It's My Will (2005) 29 OGG 841 BECK Guero (2005) 36 OGG 840 FELIX DA HOUSECAT Ft Devin Drazzle-The Neon Fever (2005) 46 CBR 840 LIFEHOUSE Lifehouse (2005) 31 OGG 840 VARIOUS ARTISTS 80s Collection Vol. 3 (2005) 36 OGG 840 VARIOUS ARTISTS Ice Princess OST (2005) 57 VBR 840 VARIOUS ARTISTS Lollihits_Fruhlings Spass! (2005) 45 OGG 840 VARIOUS ARTISTS Nordkraft OST (2005) 94 VBR 840 VARIOUS ARTISTS Play House Vol. 8 (2CD 2005) 186 VBR 840 VARIOUS ARTISTS RTL2 Pres. Party Power Charts Vol.1 (2CD 2005) 163 VBR 840 VARIOUS ARTISTS Essential R&B Spring 2005 (2CD 2005) 158 VBR 839 VARIOUS ARTISTS Remixland 2005 (2CD 2005) 205 CBR 839 VARIOUS ARTISTS RTL2 Praesentiert X-Trance Vol.1 (2CD 2005) 189 VBR 839 VARIOUS ARTISTS Trance 2005 Vol. 2 (2CD 2005) 159 VBR 839 HAGGARD Eppur Si Muove (2004) 46 CBR 838 MOONSORROW Kivenkantaja (2003) 74 CBR 838 OST John Ottman - Hide And Seek (2005) 23 OGG 838 TEMNOJAR Echo of Hyperborea (2003) 29 CBR 838 THE BRAVERY The Bravery (2005) 45 VBR 838 THRUDVANGAR Ahnenthron (2004) 62 VBR 838 VARIOUS ARTISTS 70's-80's Dance Collection (2005) 49 OGG 838 VARIOUS ARTISTS Future Trance Vol. -

Karaoke Book

10 YEARS 3 DOORS DOWN 3OH!3 Beautiful Be Like That Follow Me Down (Duet w. Neon Hitch) Wasteland Behind Those Eyes My First Kiss (Solo w. Ke$ha) 10,000 MANIACS Better Life StarStrukk (Solo & Duet w. Katy Perry) Because The Night Citizen Soldier 3RD STRIKE Candy Everybody Wants Dangerous Game No Light These Are Days Duck & Run Redemption Trouble Me Every Time You Go 3RD TYME OUT 100 PROOF AGED IN SOUL Going Down In Flames Raining In LA Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 3T 10CC Here Without You Anything Donna It's Not My Time Tease Me Dreadlock Holiday Kryptonite Why (w. Michael Jackson) I'm Mandy Fly Me Landing In London (w. Bob Seger) 4 NON BLONDES I'm Not In Love Let Me Be Myself What's Up Rubber Bullets Let Me Go What's Up (Acoustative) Things We Do For Love Life Of My Own 4 PM Wall Street Shuffle Live For Today Sukiyaki 110 DEGREES IN THE SHADE Loser 4 RUNNER Is It Really Me Road I'm On Cain's Blood 112 Smack Ripples Come See Me So I Need You That Was Him Cupid Ticket To Heaven 42ND STREET Dance With Me Train 42nd Street 4HIM It's Over Now When I'm Gone Basics Of Life Only You (w. Puff Daddy, Ma$e, Notorious When You're Young B.I.G.) 3 OF HEARTS For Future Generations Peaches & Cream Arizona Rain Measure Of A Man U Already Know Love Is Enough Sacred Hideaway 12 GAUGE 30 SECONDS TO MARS Where There Is Faith Dunkie Butt Closer To The Edge Who You Are 12 STONES Kill 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER Crash Rescue Me Amnesia Far Away 311 Don't Stop Way I Feel All Mixed Up Easier 1910 FRUITGUM CO. -

Media Ecologies: Materialist Energies in Art and Technoculture, Matthew Fuller, 2005 Media Ecologies

M796883front.qxd 8/1/05 11:15 AM Page 1 Media Ecologies Media Ecologies Materialist Energies in Art and Technoculture Matthew Fuller In Media Ecologies, Matthew Fuller asks what happens when media systems interact. Complex objects such as media systems—understood here as processes, or ele- ments in a composition as much as “things”—have become informational as much as physical, but without losing any of their fundamental materiality. Fuller looks at this multi- plicitous materiality—how it can be sensed, made use of, and how it makes other possibilities tangible. He investi- gates the ways the different qualities in media systems can be said to mix and interrelate, and, as he writes, “to produce patterns, dangers, and potentials.” Fuller draws on texts by Félix Guattari and Gilles Deleuze, as well as writings by Friedrich Nietzsche, Marshall McLuhan, Donna Haraway, Friedrich Kittler, and others, to define and extend the idea of “media ecology.” Arguing that the only way to find out about what happens new media/technology when media systems interact is to carry out such interac- tions, Fuller traces a series of media ecologies—“taking every path in a labyrinth simultaneously,” as he describes one chapter. He looks at contemporary London-based pirate radio and its interweaving of high- and low-tech “Media Ecologies offers an exciting first map of the mutational body of media systems; the “medial will to power” illustrated by analog and digital media technologies. Fuller rethinks the generation and “the camera that ate itself”; how, as seen in a range of interaction of media by connecting the ethical and aesthetic dimensions compelling interpretations of new media works, the capac- of perception.” ities and behaviors of media objects are affected when —Luciana Parisi, Leader, MA Program in Cybernetic Culture, University of they are in “abnormal” relationships with other objects; East London and each step in a sequence of Web pages, Cctv—world wide watch, that encourages viewers to report crimes seen Media Ecologies via webcams. -

“Ready to Die” 1994–2017 MA CCC CENTRAL SAINT MARTINS

“Ready To Die” 1994–2017 MA CCC CENTRAL SAINT MARTINS 1 F.Sargentone march 2017 ed: /2 2 READY TO BE The Anti-Cinematographic eye Writing an introduction to this publication has probably been one of the most difficult things I have ever done in the recent years. I thought it could have been easy to talk about one of the most influential records of the whole music history. It turned out that this loose, A5 –sized, home printed book- let is the only existing monographic work on Notorius B.I.G.’s Ready To Die. By stating this at the beginning of the sup- posed dissertation, I want to make sure that the reader could read these lines as the raw output of a deep, although instinc- tive, research on one of the milestones of hip-hop cultural history. The research pro- cess, of which this booklet testifies the ma- terial result, has been spontaneous, in the sense that did not started as a canonical research question, but instead it happened a posteriori, being the record a very famil- iar matter for me since ages. As you will see, the lyrics of the songs contained within Ready To Die are formal- ly printed –without any additional editing– from RapGenius, a world famous website collecting lyrics and anecdotes of hip-hop songs from users. The oral history com- ponent of this platform is an essential el- ement shared with early hip-hop culture, in which realities existed and formalised themselves only via word of mouth or so- cio-cultural affinity with the hip-hop phe- nomenon. -

No Time to Chill for New Members

COMMUNITY PROFILE OPINION ENVIRONMENT BROOKLYN BOY CALLS SM HOME PAGE 3 OFFICIALS OFFER NONSENSE PAGE 4 TOO MUCH GOOD STUFF PAGE 9 Visit us online at smdp.com MONDAY, JULY 2, 2007 Volume 6 Issue 198 Santa Monica Daily Press WAXMAN ASSAILS FEDS SEE PAGE 8 Since 2001: A news odyssey THE BACK AND EVEN BETTER ISSUE No time to chill for new members raise, spurring a string of events that called into question kindergarten at Will Rogers Elementary School, working her Pye, Snell forced to acclimate the financial transparency of district officials. way through the system, serving on oversight committees and The rest is Santa Monica-Malibu history. the Community for Excellent Public Schools. quickly during time on board It wasn’t the traditional welcome for two new school They both decided to put their name in the running for board members, thrust into a situation in which the school board for the same reasons, with dreams of helping BY MELODY HANATANI I Daily Press Staff Writer board and district were facing intense scrutiny by parents a district that had been good to their kids, hoping to lend and later the City Council. their expertise — Snell an accountant and Pye with execu- SMMUSD HDQTRS The honeymoon was over quickly. “I went right to work!” Pye said. tive and managerial experience in the newspaper industry. During a Nov. 16 Board of Education meeting last year, Today, Pye and Snell say they take the past eight months on Though he comes from an accounting background, fresh faces Kelly McMahon Pye and Barry Snell sat near the Board of Education as a great learning experience and are Snell said he had very little knowledge of the inner work- the back of the City Council Chambers, watching as the pleased with the way the administration handled the criticism. -

Considering the Worthy Sacrifice Hip Hop Artists May Need to Make to Reclaim the Heart of Hip Hop, Its People

It’s Not Me, It’s You: Considering the Worthy Sacrifice Hip Hop Artists May Need to Make to Reclaim the Heart of Hip Hop, its People by Sharieka Shontae Botex April, 2019 Director of Thesis: Dr. Wendy Sharer Major Department: English The origins of Hip Hop evidence that the art form was intended to provide more than music to listen to, but instead offer art that delivers messages on behalf of people who were not always listened to. My thesis offers an analysis of Jay-Z and J. Cole’s lyrical content and adds to an ongoing discussion of the potential Hip Hop artists have to be effective leaders for the Black community, whose lyrical content can be used to make positive change in society, and how this ability at times can be compromised by creating content that doesn’t evidence this potential or undermines it. Along with this, my work highlights how some of Jay-Z and J. Cole’s lyrical content exhibits their use of some rhetorical strategies and techniques used in social movements and their use of some African American rhetorical practices and strategies. In addition to this, I acknowledge and discuss points in scholarship that connect with my discussion of their lyrical content, or that aided me in proposing what they could consider for future lyrical content. I analyzed six Jay-Z songs and six J. Cole songs, including one song from their earliest released studio album and one from their most recently released studio album. I examined their lyrical content to document responses to the following questions: What issues and topics are discussed in the lyrics; Is money referenced? If so, how; Is there a message of uplift or unity?; What does the artist speak out against?; What lifestyles and habits are promoted?; What guidance is provided?; What problems are mentioned? and What solutions are offered? In my thesis, I explored Jay-Z and J. -

TUNECODE WORK TITLE Value Range 289693DR

TUNECODE WORK_TITLE Value Range 289693DR It S Everyday Bro ££££ 329418BM Boys Are So Ugh ££££ 060461CU Sex On Fire ££££ 258202LN Liar Liar ££££ 2680048Z Willy Can You Hear Me? ££££ 128318GR The Way ££££ 217278AV Better When I'm Dancing ££££ 223575FM I Ll Show You ££££ 188659KN Do It Again ££££ 136476HS Courtesy Call ££££ 224684HN Purpose ££££ 017788KU Police Escape ££££ 065640KQ Android Porn (Si Begg Remix) ££££ 189362ET Nyanyanyanyanyanyanya! ££££ 191745LU Be Right There ££££ 236174HW All Night ££££ 271523CQ Harlem Spartans - (Blanco Zico Bis Tg Millian Mizormac) ££££ 237567AM Baby Ko Bass Pasand Hai ££££ 099044DP Friday ££££ 5416917H The Big Chop ££££ 263572FQ Nasty ££££ 065810AV Dispatches ££££ 258985BW Angels ££££ 031243LQ Cha-Cha Slide ££££ 250248GN Friend Zone ££££ 235513CW Money Longer ££££ 231933KN Gold Slugs ££££ 221237KT Feel Invincible ££££ 237537FQ Friends With Benefits (Fwb) ££££ 228372EW Election 2016 ££££ 177322AR Dancing In The Sky ££££ 006520KS I Wish I Knew How It Would Feel To Be Free ££££ 153086KV Centuries ££££ 241982EN I Love The 90s ££££ 187217FT Pony (Jump On It) ££££ 134531BS My Nigga ££££ 015785EM Regulate ££££ 186800KT Nasty Freestyle ££££ 251426BW M.I.L.F. $ ££££ 238296BU Blessings Pt. 1 ££££ 238847KQ Lovers Medley ££££ 003981ER Anthem ££££ 037965FQ She Hates Me ££££ 216680GW Without You ££££ 079929CR Let's Do It Again ££££ 052042GM Before He Cheats ££££ 132883KT Baraka Allahu Lakuma ££££ 231618AW Believe In Your Barber ££££ 261745CM Ooouuu ££££ 220830ET Funny ££££ 268463EQ 16 ££££ 043343KV Couldn't Be The Girl