Marshall Stone in Latin America

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transactions American Mathematical Society

TRANSACTIONS OF THE AMERICAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY EDITED BY A. A. ALBERT OSCAR ZARISKI ANTONI ZYGMUND WITH THE COOPERATION OF RICHARD BRAUER NELSON DUNFORD WILLIAM FELLER G. A. HEDLUND NATHAN JACOBSON IRVING KAPLANSKY S. C. KLEENE M. S. KNEBELMAN SAUNDERS MacLANE C. B. MORREY W. T. REID O. F. G. SCHILLING N. E. STEENROD J. J. STOKER D. J. STRUIK HASSLER WHITNEY R. L. WILDER VOLUME 62 JULY TO DECEMBER 1947 PUBLISHED BY THE SOCIETY MENASHA, WIS., AND NEW YORK 1947 Reprinted with the permission of The American Mathematical Society Johnson Reprint Corporation Johnson Reprint Company Limited 111 Fifth Avenue, New York, N. Y. 10003 Berkeley Square House, London, W. 1 First reprinting, 1964, Johnson Reprint Corporation PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA TABLE OF CONTENTS VOLUME 62, JULY TO DECEMBER, 1947 Arens, R. F., and Kelley, J. L. Characterizations of the space of con- tinuous functions over a compact Hausdorff space. 499 Baer, R. Direct decompositions. 62 Bellman, R. On the boundedness of solutions of nonlinear differential and difference equations. 357 Bergman, S. Two-dimensional subsonic flows of a compressible fluid and their singularities. 452 Blumenthal, L. M. Congruence and superposability in elliptic space.. 431 Chang, S. C. Errata for Contributions to projective theory of singular points of space curves. 548 Day, M. M. Polygons circumscribed about closed convex curves. 315 Day, M. M. Some characterizations of inner-product spaces. 320 Dushnik, B. Maximal sums of ordinals. 240 Eilenberg, S. Errata for Homology of spaces with operators. 1. 548 Erdös, P., and Fried, H. On the connection between gaps in power series and the roots of their partial sums. -

Publications of Members, 1930-1954

THE INSTITUTE FOR ADVANCED STUDY PUBLICATIONS OF MEMBERS 1930 • 1954 PRINCETON, NEW JERSEY . 1955 COPYRIGHT 1955, BY THE INSTITUTE FOR ADVANCED STUDY MANUFACTURED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BY PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS, PRINCETON, N.J. CONTENTS FOREWORD 3 BIBLIOGRAPHY 9 DIRECTORY OF INSTITUTE MEMBERS, 1930-1954 205 MEMBERS WITH APPOINTMENTS OF LONG TERM 265 TRUSTEES 269 buH FOREWORD FOREWORD Publication of this bibliography marks the 25th Anniversary of the foundation of the Institute for Advanced Study. The certificate of incorporation of the Institute was signed on the 20th day of May, 1930. The first academic appointments, naming Albert Einstein and Oswald Veblen as Professors at the Institute, were approved two and one- half years later, in initiation of academic work. The Institute for Advanced Study is devoted to the encouragement, support and patronage of learning—of science, in the old, broad, undifferentiated sense of the word. The Institute partakes of the character both of a university and of a research institute j but it also differs in significant ways from both. It is unlike a university, for instance, in its small size—its academic membership at any one time numbers only a little over a hundred. It is unlike a university in that it has no formal curriculum, no scheduled courses of instruction, no commitment that all branches of learning be rep- resented in its faculty and members. It is unlike a research institute in that its purposes are broader, that it supports many separate fields of study, that, with one exception, it maintains no laboratories; and above all in that it welcomes temporary members, whose intellectual development and growth are one of its principal purposes. -

J´Ozef Marcinkiewicz

JOZEF¶ MARCINKIEWICZ: ANALYSIS AND PROBABILITY N. H. BINGHAM, Imperial College London Pozna¶n,30 June 2010 JOZEF¶ MARCINKIEWICZ Life Born 4 March 1910, Cimoszka, Bialystok, Poland Student, 1930-33, University of Stefan Batory in Wilno (professors Stefan Kempisty, Juliusz Rudnicki and Antoni Zygmund) 1931-32: taught Lebesgue integration and trigono- metric series by Zygmund MA 1933; military service 1933-34 PhD 1935, under Zygmund 1935-36, Fellowship, U. Lw¶ow,with Kaczmarz and Schauder 1936, senior assistant, Wilno; dozent, 1937 Spring 1939, Fellowship, Paris; o®ered chair by U. Pozna¶n August 1939: in England; returned to Poland in anticipation of war (he was an o±cer in the reserve); already in uniform by 2 September Second lieutenant, 2nd Battalion, 205th In- fantry Regiment Defence of Lwo¶w12 - 21 September 1939; Lwo¶wsurrendered to Red (Soviet) Army Prisoner of war 25 September ("temporary in- ternment" by USSR); taken to Starobielsk Presumed executed Starobielsk, or Kharkov, or Kozielsk, or Katy¶n;Katy¶nMassacre commem- orated on 10 April Work We outline (most of) the main areas in which M's influence is directly seen today, and sketch the current state of (most of) his areas of in- terest { all in a very healthy state, an indication of M's (and Z's) excellent mathematical taste. 55 papers 1933-45 (the last few posthumous) Collaborators: Zygmund 15, S. Bergman 2, B. Jessen, S. Kaczmarz, R. Salem Papers (analysed by Zygmund) on: Functions of a real variable Trigonometric series Trigonometric interpolation Functional operations Orthogonal systems Functions of a complex variable Calculus of probability MATHEMATICS IN POLAND BETWEEN THE WARS K. -

Emil Artin in America

MATHEMATICAL PERSPECTIVES BULLETIN (New Series) OF THE AMERICAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY Volume 50, Number 2, April 2013, Pages 321–330 S 0273-0979(2012)01398-8 Article electronically published on December 18, 2012 CREATING A LIFE: EMIL ARTIN IN AMERICA DELLA DUMBAUGH AND JOACHIM SCHWERMER 1. Introduction In January 1933, Adolf Hitler and the Nazi party assumed control of Germany. On 7 April of that year the Nazis created the notion of “non-Aryan descent”.1 “It was only a question of time”, Richard Brauer would later describe it, “until [Emil] Artin, with his feeling for individual freedom, his sense of justice, his abhorrence of physical violence would leave Germany” [5, p. 28]. By the time Hitler issued the edict on 26 January 1937, which removed any employee married to a Jew from their position as of 1 July 1937,2 Artin had already begun to make plans to leave Germany. Artin had married his former student, Natalie Jasny, in 1929, and, since she had at least one Jewish grandparent, the Nazis classified her as Jewish. On 1 October 1937, Artin and his family arrived in America [19, p. 80]. The surprising combination of a Roman Catholic university and a celebrated American mathematician known for his gnarly personality played a critical role in Artin’s emigration to America. Solomon Lefschetz had just served as AMS president from 1935–1936 when Artin came to his attention: “A few days ago I returned from a meeting of the American Mathematical Society where as President, I was particularly well placed to know what was going on”, Lefschetz wrote to the president of Notre Dame on 12 January 1937, exactly two weeks prior to the announcement of the Hitler edict that would influence Artin directly. -

Right Ideals of a Ring and Sublanguages of Science

RIGHT IDEALS OF A RING AND SUBLANGUAGES OF SCIENCE Javier Arias Navarro Ph.D. In General Linguistics and Spanish Language http://www.javierarias.info/ Abstract Among Zellig Harris’s numerous contributions to linguistics his theory of the sublanguages of science probably ranks among the most underrated. However, not only has this theory led to some exhaustive and meaningful applications in the study of the grammar of immunology language and its changes over time, but it also illustrates the nature of mathematical relations between chunks or subsets of a grammar and the language as a whole. This becomes most clear when dealing with the connection between metalanguage and language, as well as when reflecting on operators. This paper tries to justify the claim that the sublanguages of science stand in a particular algebraic relation to the rest of the language they are embedded in, namely, that of right ideals in a ring. Keywords: Zellig Sabbetai Harris, Information Structure of Language, Sublanguages of Science, Ideal Numbers, Ernst Kummer, Ideals, Richard Dedekind, Ring Theory, Right Ideals, Emmy Noether, Order Theory, Marshall Harvey Stone. §1. Preliminary Word In recent work (Arias 2015)1 a line of research has been outlined in which the basic tenets underpinning the algebraic treatment of language are explored. The claim was there made that the concept of ideal in a ring could account for the structure of so- called sublanguages of science in a very precise way. The present text is based on that work, by exploring in some detail the consequences of such statement. §2. Introduction Zellig Harris (1909-1992) contributions to the field of linguistics were manifold and in many respects of utmost significance. -

A Century of Mathematics in America, Peter Duren Et Ai., (Eds.), Vol

Garrett Birkhoff has had a lifelong connection with Harvard mathematics. He was an infant when his father, the famous mathematician G. D. Birkhoff, joined the Harvard faculty. He has had a long academic career at Harvard: A.B. in 1932, Society of Fellows in 1933-1936, and a faculty appointmentfrom 1936 until his retirement in 1981. His research has ranged widely through alge bra, lattice theory, hydrodynamics, differential equations, scientific computing, and history of mathematics. Among his many publications are books on lattice theory and hydrodynamics, and the pioneering textbook A Survey of Modern Algebra, written jointly with S. Mac Lane. He has served as president ofSIAM and is a member of the National Academy of Sciences. Mathematics at Harvard, 1836-1944 GARRETT BIRKHOFF O. OUTLINE As my contribution to the history of mathematics in America, I decided to write a connected account of mathematical activity at Harvard from 1836 (Harvard's bicentennial) to the present day. During that time, many mathe maticians at Harvard have tried to respond constructively to the challenges and opportunities confronting them in a rapidly changing world. This essay reviews what might be called the indigenous period, lasting through World War II, during which most members of the Harvard mathe matical faculty had also studied there. Indeed, as will be explained in §§ 1-3 below, mathematical activity at Harvard was dominated by Benjamin Peirce and his students in the first half of this period. Then, from 1890 until around 1920, while our country was becoming a great power economically, basic mathematical research of high quality, mostly in traditional areas of analysis and theoretical celestial mechanics, was carried on by several faculty members. -

Toward a New Science of Information

Data Science Journal, Volume 6, Supplement, 7 April 2007 TOWARD A NEW SCIENCE OF INFORMATION D Doucette1*, R Bichler 2, W Hofkirchner2, and C Raffl2 *1 The Science of Information Institute, 1737 Q Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20009, USA Email: [email protected] 2 ICT&S Center, University of Salzburg - Center for Advanced Studies and Research in Information and Communication Technologies & Society, Sigmund-Haffner-Gasse 18, 5020 Salzburg, Austria Email: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] ABSTRACT The concept of information has become a crucial topic in several emerging scientific disciplines, as well as in organizations, in companies and in everyday life. Hence it is legitimate to speak of the so-called information society; but a scientific understanding of the Information Age has not had time to develop. Following this evolution we face the need of a new transdisciplinary understanding of information, encompassing many academic disciplines and new fields of interest. Therefore a Science of Information is required. The goal of this paper is to discuss the aims, the scope, and the tools of a Science of Information. Furthermore we describe the new Science of Information Institute (SOII), which will be established as an international and transdisciplinary organization that takes into consideration a larger perspective of information. Keywords: Information, Science of Information, Information Society, Transdisciplinarity, Science of Information Institute (SOII), Foundations of Information Science (FIS) 1 INTRODUCTION Information is emerging as a new and large prospective area of study. The notion of information has become a crucial topic in several emerging scientific disciplines such as Philosophy of Information, Quantum Information, Bioinformatics and Biosemiotics, Theory of Mind, Systems Theory, Internet Research, and many more. -

Marshall Stone Y Las Matemáticas

MARSHALL STONE Y LAS MATEMÁTICAS Referencia: 1998. Semanario Universidad, San José. Costa Rica. Marshall Harvey Stone nació en Nueva York el 8 de abril de 1903. A los 16 años entró a Harvard y se graduó summa cum laude en 1922. Antes de ser profesor de Harvard entre 1933 y 1946, fue profesor en Columbia (1925-1927), Harvard (1929-1931), Yale (1931-1933) y Stanford en el verano de 1933. Aunque graduado y profesor en Harvard University, se conoce más por haber convertido el Departamento de Matemática de la University of Chicago -como su Director- en uno de los principales centros matemáticos del mundo, lo que logró con la contratación de los famosos matemáticos Andre Weil, S. S. Chern, Antoni Zygmund, Saunders Mac Lane y Adrian Albert. También fueron contratados en esa época: Paul Halmos, Irving Seal y Edwin Spanier. Para Saunders Mac Lane, el Departamento de Matemática que constituyó Stone en Chicago fue en su momento “sin duda el departamento de matemáticas líder en el país”., y probablemente, deberíamos añadir, en el mundo. Los méritos científicos de Stone fueron muchos. Cuando llegó a Chicago en 1946, por recomendación de John von Neumann al presidente de la Universidad de Chicago, ya había realizado importantes trabajos en varias áreas matemáticas, por ejemplo: la teoría espectral de operadores autoadjuntos en espacios de Hilbert y en las propiedades algebraicas de álgebras booleanas en el estudio de anillos de funciones continuas. Se le conoce por el famoso teorema de Stone Weierstrass, así como la compactificación de Stone Cech. Su libro más influyente fue Linear Transformations in Hilbert Space and their Application to Analysis. -

Writing the History of Dynamical Systems and Chaos

Historia Mathematica 29 (2002), 273–339 doi:10.1006/hmat.2002.2351 Writing the History of Dynamical Systems and Chaos: View metadata, citation and similar papersLongue at core.ac.uk Dur´ee and Revolution, Disciplines and Cultures1 brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector David Aubin Max-Planck Institut fur¨ Wissenschaftsgeschichte, Berlin, Germany E-mail: [email protected] and Amy Dahan Dalmedico Centre national de la recherche scientifique and Centre Alexandre-Koyre,´ Paris, France E-mail: [email protected] Between the late 1960s and the beginning of the 1980s, the wide recognition that simple dynamical laws could give rise to complex behaviors was sometimes hailed as a true scientific revolution impacting several disciplines, for which a striking label was coined—“chaos.” Mathematicians quickly pointed out that the purported revolution was relying on the abstract theory of dynamical systems founded in the late 19th century by Henri Poincar´e who had already reached a similar conclusion. In this paper, we flesh out the historiographical tensions arising from these confrontations: longue-duree´ history and revolution; abstract mathematics and the use of mathematical techniques in various other domains. After reviewing the historiography of dynamical systems theory from Poincar´e to the 1960s, we highlight the pioneering work of a few individuals (Steve Smale, Edward Lorenz, David Ruelle). We then go on to discuss the nature of the chaos phenomenon, which, we argue, was a conceptual reconfiguration as -

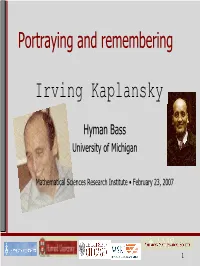

Irving Kaplansky

Portraying and remembering Irving Kaplansky Hyman Bass University of Michigan Mathematical Sciences Research Institute • February 23, 2007 1 Irving (“Kap”) Kaplansky “infinitely algebraic” “I liked the algebraic way of looking at things. I’m additionally fascinated when the algebraic method is applied to infinite objects.” 1917 - 2006 A Gallery of Portraits 2 Family portrait: Kap as son • Born 22 March, 1917 in Toronto, (youngest of 4 children) shortly after his parents emigrated to Canada from Poland. • Father Samuel: Studied to be a rabbi in Poland; worked as a tailor in Toronto. • Mother Anna: Little schooling, but enterprising: “Health Bread Bakeries” supported (& employed) the whole family 3 Kap’s father’s grandfather Kap’s father’s parents Kap (age 4) with family 4 Family Portrait: Kap as father • 1951: Married Chellie Brenner, a grad student at Harvard Warm hearted, ebullient, outwardly emotional (unlike Kap) • Three children: Steven, Alex, Lucy "He taught me and my brothers a lot, (including) what is really the most important lesson: to do the thing you love and not worry about making money." • Died 25 June, 2006, at Steven’s home in Sherman Oaks, CA Eight months before his death he was still doing mathematics. Steven asked, -“What are you working on, Dad?” -“It would take too long to explain.” 5 Kap & Chellie marry 1951 Family portrait, 1972 Alex Steven Lucy Kap Chellie 6 Kap – The perfect accompanist “At age 4, I was taken to a Yiddish musical, Die Goldene Kala. It was a revelation to me that there could be this kind of entertainment with music. -

The Intellectual Journey of Hua Loo-Keng from China to the Institute for Advanced Study: His Correspondence with Hermann Weyl

ISSN 1923-8444 [Print] Studies in Mathematical Sciences ISSN 1923-8452 [Online] Vol. 6, No. 2, 2013, pp. [71{82] www.cscanada.net DOI: 10.3968/j.sms.1923845220130602.907 www.cscanada.org The Intellectual Journey of Hua Loo-keng from China to the Institute for Advanced Study: His Correspondence with Hermann Weyl Jean W. Richard[a],* and Abdramane Serme[a] [a] Department of Mathematics, The City University of New York (CUNY/BMCC), USA. * Corresponding author. Address: Department of Mathematics, The City University of New York (CUN- Y/BMCC), 199 Chambers Street, N-599, New York, NY 10007-1097, USA; E- Mail: [email protected] Received: February 4, 2013/ Accepted: April 9, 2013/ Published: May 31, 2013 \The scientific knowledge grows by the thinking of the individual solitary scientist and the communication of ideas from man to man Hua has been of great value in this respect to our whole group, especially to the younger members, by the stimulus which he has provided." (Hermann Weyl in a letter about Hua Loo-keng, 1948).y Abstract: This paper explores the intellectual journey of the self-taught Chinese mathematician Hua Loo-keng (1910{1985) from Southwest Associ- ated University (Kunming, Yunnan, China)z to the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton. The paper seeks to show how during the Sino C Japanese war, a genuine cross-continental mentorship grew between the prolific Ger- man mathematician Hermann Weyl (1885{1955) and the gifted mathemati- cian Hua Loo-keng. Their correspondence offers a profound understanding of a solidarity-building effort that can exist in the scientific community. -

Mathematicians Fleeing from Nazi Germany

Mathematicians Fleeing from Nazi Germany Mathematicians Fleeing from Nazi Germany Individual Fates and Global Impact Reinhard Siegmund-Schultze princeton university press princeton and oxford Copyright 2009 © by Princeton University Press Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW All Rights Reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Siegmund-Schultze, R. (Reinhard) Mathematicians fleeing from Nazi Germany: individual fates and global impact / Reinhard Siegmund-Schultze. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-691-12593-0 (cloth) — ISBN 978-0-691-14041-4 (pbk.) 1. Mathematicians—Germany—History—20th century. 2. Mathematicians— United States—History—20th century. 3. Mathematicians—Germany—Biography. 4. Mathematicians—United States—Biography. 5. World War, 1939–1945— Refuges—Germany. 6. Germany—Emigration and immigration—History—1933–1945. 7. Germans—United States—History—20th century. 8. Immigrants—United States—History—20th century. 9. Mathematics—Germany—History—20th century. 10. Mathematics—United States—History—20th century. I. Title. QA27.G4S53 2008 510.09'04—dc22 2008048855 British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available This book has been composed in Sabon Printed on acid-free paper. ∞ press.princeton.edu Printed in the United States of America 10 987654321 Contents List of Figures and Tables xiii Preface xvii Chapter 1 The Terms “German-Speaking Mathematician,” “Forced,” and“Voluntary Emigration” 1 Chapter 2 The Notion of “Mathematician” Plus Quantitative Figures on Persecution 13 Chapter 3 Early Emigration 30 3.1. The Push-Factor 32 3.2. The Pull-Factor 36 3.D.