Volume 61, 2018 – Online Excavation Reports

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alex R. Knodell, Sylvian Fachard, Kalliopi Papangeli

ALEX R. KNODELL, SYLVIAN FACHARD, KALLIOPI PAPANGELI THE MAZI ARCHAEOLOGICAL PROJECT 2016: SURVEY AND SETTLEMENT INVESTIGATIONS IN NORTHWEST ATTICA (GREECE) offprint from antike kunst, volume 60, 2017 10_Separatum_Fachard.indd 3 23.08.17 11:22 THE MAZI ARCHAEOLOGICAL PROJECT 2016: SURVEY AND SETTLEMENT INVESTIGATIONS IN NORTHWEST ATTICA (GREECE) Alex R Knodell, Sylvian Fachard, Kalliopi Papangeli Introduction Digital initiatives in high-resolution mapping and three-dimensional recording of archaeological features The 2016 field season of the Mazi Archaeological Pro- continued through the investigation of several sites Tar- ject (MAP) involved multiple components: intensive and geted cleaning at the prehistoric site of Kato Kastanava extensive pedestrian survey, digital and traditional meth- yielded ambiguous results, especially in terms of the ods of documenting archaeological features, cleaning op- architectural remains, some of which are clearly early erations at sites of particular significance, geophysical modern; however, the analysis of the pottery and the lith- survey, and artifact analysis and study1 The intensive ics confirmed the presence of a Neolithic/Early Helladic survey expanded upon the 2014–2015 work of the project occupation at the site Cleaning at the Eleutherai fortress to focus on the middle of the plain (Area d) and the allowed for the production of the first comprehensive Kastanava Valley, yielding new information regarding the plan of the site; further investigations confirmed the ex- main periods of occupation -

NEW EOT-English:Layout 1

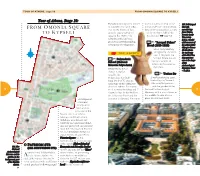

TOUR OF ATHENS, stage 10 FROM OMONIA SQUARE TO KYPSELI Tour of Athens, Stage 10: Papadiamantis Square), former- umental staircases lead to the 107. Bell-shaped FROM MONIA QUARE ly a garden city (with villas, Ionian style four-column propy- idol with O S two-storey blocks of flats, laea of the ground floor, a copy movable legs TO K YPSELI densely vegetated) devel- of the northern hall of the from Thebes, oped in the 1920’s - the Erechteion ( page 13). Boeotia (early 7th century suburban style has been B.C.), a model preserved notwithstanding 1.2 ¢ “Acropol Palace” of the mascot of subsequent development. Hotel (1925-1926) the Athens 2004 Olympic Games A five-story building (In the photo designed by the archi- THE SIGHTS: an exact copy tect I. Mayiasis, the of the idol. You may purchase 1.1 ¢Polytechnic Acropol Palace is a dis- tinctive example of one at the shops School (National Athens Art Nouveau ar- of the Metsovio Polytechnic) Archaeological chitecture. Designed by the ar- Resources Fund – T.A.P.). chitect L. Kaftan - 1.3 tzoglou, the ¢Tositsa Str Polytechnic was built A wide pedestrian zone, from 1861-1876. It is an flanked by the National archetype of the urban tra- Metsovio Polytechnic dition of Athens. It compris- and the garden of the 72 es of a central building and T- National Archaeological 73 shaped wings facing Patision Museum, with a row of trees in Str. It has two floors and the the middle, Tositsa Str is a development, entrance is elevated. Two mon- place to relax and stroll. -

Networking UNDERGROUND Archaeological and Cultural Sites: the CASE of the Athens Metro

ing”. Indeed, since that time, the archaeological NETWORKING UNDERGROUND treasures found in other underground spaces are very often displayed in situ and in continu- ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND ity with the cultural and archaeological spaces of the surface (e.g. in the building of the Central CULTURAL SITES: THE CASE Bank of Greece). In this context, the present paper presents OF THE ATHENS METRO the case of the Athens Metro and the way that this common use of the underground space can have an alternative, more sophisticated use, Marilena Papageorgiou which can also serve to enhance the city’s iden- tity. Furthermore, the case aims to discuss the challenges for Greek urban planners regarding the way that the underground space of Greece, so rich in archaeological artifacts, can become part of an integrated and holistic spatial plan- INTRODUCTION: THE USE OF UNDERGROUND SPACE IN GREECE ning process. Greece is a country that doesn’t have a very long tradition either in building high ATHENS IN LAYERS or in using its underground space for city development – and/or other – purposes. In fact, in Greece, every construction activity that requires digging, boring or tun- Key issues for the Athens neling (public works, private building construction etc) is likely to encounter an- Metropolitan Area tiquities even at a shallow depth. Usually, when that occurs, the archaeological 1 · Central Athens 5 · Piraeus authorities of the Ministry of Culture – in accordance with the Greek Archaeologi- Since 1833, Athens has been the capital city of 2 · South Athens 6 · Islands 3 · North Athens 7 · East Attica 54 cal Law 3028 - immediately stop the work and start to survey the area of interest. -

The Catastrophic Fire of July 2018 in Greece and the Report of the Independent Committee That Was Appointed by the Government To

First General Assembly & 2nd MC meeting October 8-9, 2018, Sofia, Bulgaria The catastrophic fire of July 2018 in Greece and the Report of the Independent Committee that was appointed by the government to investigate the reasons for the worsening wildfire trend in the country Gavriil Xanthopoulos1, Ioannis Mitsopoulos2 1Hellenic Agricultural Organization "Demeter“, Institute of Mediterranean Forest Ecosystems Athens, Greece, e-mail: [email protected] 2Hellenic Ministry of Environment and Energy Athens, Greece, e-mail: [email protected] The forest fire disaster in Attica, Greece, on 23 July, 2018 The situation on July 13, 2018 in Attica • On 13 July 2018, at 16:41, a wildfire broke out on the eastern slopes of Penteli mountain, 20 km NE of the center of Athens and 5.2 km from the eastern coast of Attica. • This happened on a day with very high fire danger predicted for Attica due to an unusually strong westerly wind, and while another wildfire, that had started earlier near the town of Kineta in west Attica, 50 km west of the center of Athens, was burning in full force, spreading through the town and threatening the largest refinery in the country. The smoke of the fire of Kineta as seen in the center of Athens at 13:08 Fire weather and vegetation condition • According to weather measurements at the National Observatory of Athens on Mt. Penteli, upwind of the fire, the prevailing wind was WNW with speeds ranging from 32 to 56 km/h for the first two hours after the fire start, with gusts of 50 to 89 km/h. -

Prevalence of Toxocara Canis Ova in Soil Samples Collected from Public Areas of Attica Prefecture, Greece»

«PREVALENCE OF TOXOCARA CANIS OVA IN SOIL SAMPLES COLLECTED FROM PUBLIC AREAS OF ATTICA PREFECTURE, GREECE». Vasilios Papavasilopoulos, Ioannis Elefsiniotis, Konstantinos Birbas, Vassiliki Pitiriga, Corresp. Author: Papavasilopoulos Vasilios, National School of Public Health, 196 L. Alexandras Ampelokipoi Athens, PC Athanasios Tsakris, Gerasimos Bonatsos. 11521, Greece. E-mail: [email protected] Introduction Methods Results Conclusions From March 2013 to May 2013, soil samples Toxocariasis is a parasitic zoonosis caused A total of 1510 soil sample were collected. All Attica Prefecture exhibited a high T. canis soil were collected from 33 most popular public six regions of Attica were contaminated with contamination rate, therefore individuals and by the larvae stage of roundworm Toxocara places of six large regions throughout the sp. The genus Toxocara includes more than T. canis ova. Of the total 1510 examined especially children might be at great risk for total area of Attica prefecture: (A) Central samples, T. canis ova were recovered from toxocariasis when exposed in public areas. 30 species, of which two are significant for Athens area, (B) West Attica area (C) North human infections: Toxocara canis 258 samples, suggesting an overall Preventive measures should be implemented suburbs area (D) Southern suburbs area (E) contamination proportion in Attica of 17.08%. in order to control the spread of this parasitic andToxocara cati. Toxocara canis (T. canis) Piraeus area (F) Elefsina area. The number are common inhabitants of the intestines of a (Table 2). infection. of soil samples taken from each place was high percentage of new-born puppies and analogous to its dimensions (Table 1). TOXOCARA SP. -

Cultural Heritage in the Realm of the Commons: Conversations on the Case of Greece

Stelios Lekakis Stelios Lekakis Edited by Edited by CulturalCultural heritageheritage waswas inventedinvented inin thethe realmrealm ofof nation-states,nation-states, andand fromfrom EditedEdited byby anan earlyearly pointpoint itit waswas consideredconsidered aa publicpublic good,good, stewardedstewarded toto narratenarrate thethe SteliosStelios LekakisLekakis historichistoric deedsdeeds ofof thethe ancestors,ancestors, onon behalfbehalf ofof theirtheir descendants.descendants. NowaNowa-- days,days, asas thethe neoliberalneoliberal rhetoricrhetoric wouldwould havehave it,it, itit isis forfor thethe benefitbenefit ofof thesethese tax-payingtax-paying citizenscitizens thatthat privatisationprivatisation logiclogic thrivesthrives inin thethe heritageheritage sector,sector, toto covercover theirtheir needsneeds inin thethe namename ofof socialsocial responsibilityresponsibility andand otherother truntrun-- catedcated viewsviews ofof thethe welfarewelfare state.state. WeWe areare nownow atat aa criticalcritical stage,stage, wherewhere thisthis doubledouble enclosureenclosure ofof thethe pastpast endangersendangers monuments,monuments, thinsthins outout theirtheir socialsocial significancesignificance andand manipulatesmanipulates theirtheir valuesvalues inin favourfavour ofof economisticeconomistic horizons.horizons. Conversations on the Case of Greece Conversations on the Case of Greece Cultural Heritage in the Realm of Commons: Cultural Heritage in the Realm of Commons: ThisThis volumevolume examinesexamines whetherwhether wewe cancan placeplace -

Kythera Summer Edition 2016

τυ KYTHERA ISSUEΰ Summer Edition 2016 FOUNDERρΙΔΡΥΤΗΣό ©METAXIA POULOS • PUBLISHERό DIMITRIOS KYRIAKOPOULOS •ΰEDITORό DEBORAH PARSONS •ΰWRITERSό ELIAS ANAGNOSTOUν DIONYSIS ANEMOGIANNISν ASPASIA BEYERν JEAN BINGENν ANNA COMINOSν MARIA DEFTEREVOSν MARIANNA HALKIAν PAULA KARYDISν GEORGE LAMPOGLOUν KIRIAKI ORFANOSν PIA PANARETOSν ASPASIA PATTYν HELEN TZORTξ ZOPOULOSν CAMERON WEBB • ARTWORKό DAPHNE PETROHILOS• PHOTOGRAPHYόΰDIMITRIS BALTZISν CHRISSA FATSEASν VENIA KAROLIDOUν JAMES PRINEASν VAGELIS TSIGARIDASν STELLA ZALONI • PROOF READINGό JOY TATARAKIν PAULA CASSIMATIS •ΰLAYOUT & DESIGNό MYRTO BOLOTA • EDITORIALρADVERTISINGξΣΥΝΤΑΞΗρΔΙΑΦΗΜΙΣΕΙΣό ψ9φφξχχσωτςν eξmailό kseοσ99υ@yahooοgr FREE COMMUNITY PAPER • ΕΛΛΗΝΟξΑΓΓΛΙΚΗ ΕΚΔΟΣΗ • ΑΝΕΞ ΑΡΤΗΤΗ ΠΟΛΙΤΙΣΤΙΚΗ ΕΦΗΜΕΡΙΔΑ • ΔΙΑΝΕΜΕΤΑΙ ΔΩΡΕΑΝ George & Viola Haros and family wish everyone a Happy Summer in Kythera GOLD CASTLE JEWELLERY WE BELIEVE IN TAKING CARE OF OUR CUSTOMERS, Unbeatable prices for gold and silver SO THAT THEY CAN TAKE CARE OF THEIRS. A large selection of jewellery in ττKν σ8K & σ4K gold Traditional handξmade Byzantine icons wwwοstgeorgefoodserviceοcomοau Αμαλαμβάμξσμε ειδικέπ παοαγγελίεπ καςαρκεσήπ κξρμημάςωμ και εικϊμωμ All the right ingredients CHORA Kythera: 27360-31954 6945-014857 With a view of the Mediterranean EnjoyEnjoy restingresting inin anan idyllicidyllic environment that would make the gods jealous Νιώστε στιγμές πολύτιμης ξεκούρασης Nowhere but Porto Delfino Νιόρςε ρςιγμέπ πξλϋςιμεπ νεκξϋοαρηπ σε ρεένα έμα ειδυλλιακό ιδαμικϊ πεοιβάλλξμ περιβάλλον t. +30 27360 31940 +30 -

Alex R. Knodell, Sylvian Fachard, Kalliopi Papangeli

ALEX R. KNODELL, SYLVIAN FACHARD, KALLIOPI PAPANGELI THE 2015 MAZI ARCHAEOLOGICAL PROJECT: REGIONAL SURVEY IN NORTHWEST ATTICA (GREECE) offprint from antike kunst, volume 59, 2016 THE 2015 MAZI ARCHAEOLOGICAL PROJECT: REGIONAL SURVEY IN NORTHWEST ATTICA (GREECE) Alex R. Knodell, Sylvian Fachard, Kalliopi Papangeli The Mazi Archaeological Project (MAP) is a dia- Survey areas and methods chronic regional survey of the Mazi Plain (Northwest Attica, Greece), operating as a synergasia between the In 2015 we conducted fieldwork in three zones: Areas Ephorate of Antiquities of West Attika, Pireus, and b, c, and e (fig. 1). Area a was the focus during the 2014 Islands and the Swiss School of Archaeology in Greece. field season3, between Ancient Oinoe and the Mazi This small mountain plain is characterized by its critical Tower on the eastern outskirts of Modern Oinoe. Area b location on a major land route between central and corresponds to the Kouloumbi Plain, just south of the southern Greece, and on the Attic-Boeotian borders. Mazi Plain and connected to it via a short passage named Territorial disputes in these borderlands are attested from Bozari. Area c is immediately north of Area a, in the the Late Archaic period1 and the sites of Oinoe and northeastern part of the survey area, immediately adja- Eleutherai have marked importance for the study of cent to the modern delimitation between Attica and Boe- Attic-Boeotian topography, mythology, and religion. otia. Area e is the western end of the Mazi Plain, and in- Our approach to regional history extends well beyond cludes the settlement and fortress of Eleutherai, at the the Classical past to include prehistoric precursors, as mouth of the Kaza Pass, as well as the small Prophitis well as the later history of this part of Greece. -

Social Activities Impact and Covid 19 Second Wave

Social Activities Impact and Covid 19 Presented at the FIG e-WorkingSecond Week 2021, Wave: the Case of Thessaloniki, 21-25 June 2021 in Virtually in the Netherlands Greece Dionysia - Georgia Perperidou, University of West Attica, Athens, Greece Georgios Moschopoulos, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, Greece & Dimitrios Ampatzidis, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, Greece FIG e-Working Week 2021 Smart Surveyors for Land and Water Management - Challenges in a New Reality Virtual, 21–25 June 2021 SARS - CoV-2 & COVID-19 first wave, Spring 2020 SARS - CoV-2 & COVID-19 global pandemic forced governments all around the word to take strict measures to reduce the spread of the virus from early 2020 Suspension of all face-to-face educational activities in Greece on 10 March 2020 On 22 March 2020 Greece was in total lockdown and all non-essential activities e.g. retail, entertainment, sports, religion activities were suspended along with suspensions to travels, travels between prefectures and travels for visits to family/ friends houses. For emergency purposes – daily shopping, doctor – visits, help to elders – and for personal training or dog walk, travels were allowed (first a text message ought to be sent or a personal declaration statement should be carried out and demonstrated in case of authorities control). From early March Greece’s authorities gradually suspended international air-flights. Strict border controls at border crossing took place as there was also suspension of international road travels. Only commercial international travels were permitted after justification to the authorities. Greece’s March 2020 total lockdown shield the Country from SARS - CoV-2 & COVID-19. -

Maternal and Neonatal Factors Associated with Successful Breastfeeding in Preterm Infants

International Journal of Caring Sciences January– April 2020 Volume 13 | Issue 1| Page 152 Original Article Maternal and Neonatal Factors Associated with Successful Breastfeeding in Preterm Infants Maria Daglas, RM, MSc, MPH, PhD Assistant Professor, Department of Midwifery, University of West Attica, Athens, Greece Charikleia Sidiropoulou, RM, MSc 2nd Department of Pediatrics, National & Kapodistrian University of Athens School of Medicine, 'P. & A. Kyriakou' Children's Hospital, Athens, Greece Petros Galanis, RN, MPH, PhD Department of Nursing, Center for Health Services Management and Evaluation, National & Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens, Greece Angeliki Bilali, RN, MSc, PhD 2nd Department of Pediatrics, National & Kapodistrian University of Athens School of Medicine, 'P. & A. Kyriakou' Children's Hospital, Athens, Greece Evangelia Antoniou, RM, MPH, PhD Assistant Professor, Department of Midwifery, University of West Attica, Athens, Greece Georgios Iatrakis, MD, PhD Professor, Head of Midwifery Department, University of West Attica, Athens, Greece Correspondence: Maria Daglas, Address: 38, Paradeisou Street 17123, Nea Smyrni, Athens, Greece E- mail: [email protected] Abstract Background: The nutritional value and superiority of breast milk against the commercial infant formula has been confirmed by studies results, particularly for premature neonates. Aims: The aims of this study was to: a) explore the factors that are significantly associated and affect the breastfeeding of preterm newborns after their exit from the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) and during their stay at home and b) to explore the prevalence and duration of breastfeeding (exclusive or not) in the population of premature neonates in Greece. Methodology: A cross-sectional study was conducted in 2014. A hundred mothers participated via telephone interviews in the study. -

Αthens and Attica in Prehistory Proceedings of the International Conference Athens, 27-31 May 2015

Αthens and Attica in Prehistory Proceedings of the International Conference Athens, 27-31 May 2015 edited by Nikolas Papadimitriou James C. Wright Sylvian Fachard Naya Polychronakou-Sgouritsa Eleni Andrikou Archaeopress Archaeology Archaeopress Publishing Ltd Summertown Pavilion 18-24 Middle Way Summertown Oxford OX2 7LG www.archaeopress.com ISBN 978-1-78969-671-4 ISBN 978-1-78969-672-1 (ePdf) © 2020 Archaeopress Publishing, Oxford, UK Language editing: Anastasia Lampropoulou Layout: Nasi Anagnostopoulou/Grafi & Chroma Cover: Bend, Nasi Anagnostopoulou/Grafi & Chroma (layout) Maps I-IV, GIS and Layout: Sylvian Fachard & Evan Levine (with the collaboration of Elli Konstantina Portelanou, Ephorate of Antiquities of East Attica) Cover image: Detail of a relief ivory plaque from the large Mycenaean chamber tomb of Spata. National Archaeological Museum, Athens, Department of Collection of Prehistoric, Egyptian, Cypriot and Near Eastern Antiquities, no. Π 2046. © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports, Archaeological Receipts Fund All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Printed in the Netherlands by Printforce This book is available direct from Archaeopress or from our website www.archaeopress.com Publication Sponsors Institute for Aegean Prehistory The American School of Classical Studies at Athens The J.F. Costopoulos Foundation Conference Organized by The American School of Classical Studies at Athens National and Kapodistrian University of Athens - Department of Archaeology and History of Art Museum of Cycladic Art – N.P. Goulandris Foundation Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports - Ephorate of Antiquities of East Attica Conference venues National and Kapodistrian University of Athens (opening ceremony) Cotsen Hall, American School of Classical Studies at Athens (presentations) Museum of Cycladic Art (poster session) Organizing Committee* Professor James C. -

NIKOLAOS A. STATHOPOULOS Professor at University of West

N.A.Stathopoulos CV NIKOLAOS A. STATHOPOULOS Professor at University of West Attica Department of Electrical and Electronics Engineering Thivon 250 & Petrou Ralli Str (Campus 2 – Building Z) 122 44 Egaleo Tel: +30 210 538-1486 Email: [email protected] Education 1995 PhD, DEPARTMENT OF ELECTRICAL AND COMPUTER ENGINEERING National Technical University of Athens (NTUA) 1984 DIPLOMA IN ELECTRICAL ENGINEERING National Technical University of Athens (NTUA) Research topics Propagation modes in nonlinear optical waveguides and fibers Simulation of microcavity effects in OLED devices. Outcoupling efficiency of organic photovoltaic devices OPVs. Microwave pulse compression systems Analysis and applications of fiber Bragg gratings Professional Experience 2018 – today University of West Attica (UNIWA) – Faculty of Engineering - Department of Electrical and Electronics Engineering Professor (2018 - today) 1999 – 2018 Piraeus University of Applied Sciences – PUAS (Technological Education Institute - TEI of Piraeus) Department of Electronics Engineering Professor (2008 – 2018) Associate Professor (2003-2008) Assistant Professor (1999-2002) 1995 – 1999 OPT Hellas SA RF Filter Design Engineer (1987-90, 1995-99). Head of design and development department (1997-1999) 1993 – 1994 INTRACΟΜ S.A Telecommunication Software Design Engineer _____________________________________________________________________________________________________ 1 N.A.Stathopoulos CV 1990 – 1992 Marine Technology Development Company SA Sensor Electronics Engineer Teaching in Undergraduate