Freedom and Destiny by Rollo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

February 26, 2021 Amazon Warehouse Workers In

February 26, 2021 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama are voting to form a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). We are the writers of feature films and television series. All of our work is done under union contracts whether it appears on Amazon Prime, a different streaming service, or a television network. Unions protect workers with essential rights and benefits. Most importantly, a union gives employees a seat at the table to negotiate fair pay, scheduling and more workplace policies. Deadline Amazon accepts unions for entertainment workers, and we believe warehouse workers deserve the same respect in the workplace. We strongly urge all Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer to VOTE UNION YES. In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Chris Abbott (LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE; CAGNEY AND LACEY; MAGNUM, PI; HIGH SIERRA SEARCH AND RESCUE; DR. QUINN, MEDICINE WOMAN; LEGACY; DIAGNOSIS, MURDER; BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL; YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS; CLOSE ENOUGH; A FUTILE AND STUPID GESTURE; CHILDRENS HOSPITAL; PENGUINS OF MADAGASCAR; LEVERAGE) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; GROWING PAINS; THE HOGAN FAMILY; THE PARKERS) David Abramowitz (HIGHLANDER; MACGYVER; CAGNEY AND LACEY; BUCK JAMES; JAKE AND THE FAT MAN; SPENSER FOR HIRE) Gayle Abrams (FRASIER; GILMORE GIRLS) 1 of 72 Jessica Abrams (WATCH OVER ME; PROFILER; KNOCKING ON DOORS) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Nick Adams (NEW GIRL; BOJACK HORSEMAN; -

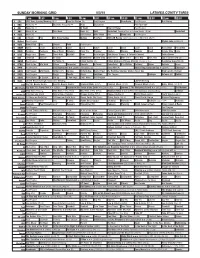

Sunday Morning Grid 5/3/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 5/3/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face the Nation (N) Paid Program NewsRadio Paid Program Bull Riding 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Equestrian PGA Tour Golf 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) NBA Basketball Brooklyn Nets at Atlanta Hawks. (N) Å Basketball 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday Midday Pre-Race NASCAR Racing Sprint Cup Series: GEICO 500. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Afghan Luke (2011) (R) 18 KSCI Breast Red Paid Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Cosas Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local RescueBot RescueBot 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Fresh Simply Ming Lidia 28 KCET Raggs Fast. Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Insight Rick Steves’ Europe: A Cultural Carnival Father Brown 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY7) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly Taxi › (2004) (PG-13) 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División: Pumas vs Azul República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program 101 Dalmatians ›› (1996) Glenn Close. -

Planetary Science Division Status Report

Planetary Science Division Status Report Jim Green NASA, Planetary Science Division January 26, 2017 Astronomy and Astrophysics Advisory CommiBee Outline • Planetary Science ObjecFves • Missions and Events Overview • Flight Programs: – Discovery – New FronFers – Mars Programs – Outer Planets • Planetary Defense AcFviFes • R&A Overview • Educaon and Outreach AcFviFes • PSD Budget Overview New Horizons exploresPlanetary Science Pluto and the Kuiper Belt Ascertain the content, origin, and evoluFon of the Solar System and the potenFal for life elsewhere! 01/08/2016 As the highest resolution images continue to beam back from New Horizons, the mission is onto exploring Kuiper Belt Objects with the Long Range Reconnaissance Imager (LORRI) camera from unique viewing angles not visible from Earth. New Horizons is also beginning maneuvers to be able to swing close by a Kuiper Belt Object in the next year. Giant IcebergsObjecve 1.5.1 (water blocks) floatingObjecve 1.5.2 in glaciers of Objecve 1.5.3 Objecve 1.5.4 Objecve 1.5.5 hydrogen, mDemonstrate ethane, and other frozenDemonstrate progress gasses on the Demonstrate Sublimation pitsDemonstrate from the surface ofDemonstrate progress Pluto, potentially surface of Pluto.progress in in exploring and progress in showing a geologicallyprogress in improving active surface.in idenFfying and advancing the observing the objects exploring and understanding of the characterizing objects The Newunderstanding of Horizons missionin the Solar System to and the finding locaons origin and evoluFon in the Solar System explorationhow the chemical of Pluto wereunderstand how they voted the where life could of life on Earth to that pose threats to and physical formed and evolve have existed or guide the search for Earth or offer People’sprocesses in the Choice for Breakthrough of thecould exist today life elsewhere resources for human Year forSolar System 2015 by Science Magazine as exploraon operate, interact well as theand evolve top story of 2015 by Discover Magazine. -

An "Authentic Wholeness" Synthesis of Jungian and Existential Analysis

Modern Psychological Studies Volume 5 Number 2 Article 3 1997 An "authentic wholeness" synthesis of Jungian and existential analysis Samuel Minier Wittenberg University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.utc.edu/mps Part of the Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Minier, Samuel (1997) "An "authentic wholeness" synthesis of Jungian and existential analysis," Modern Psychological Studies: Vol. 5 : No. 2 , Article 3. Available at: https://scholar.utc.edu/mps/vol5/iss2/3 This articles is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals, Magazines, and Newsletters at UTC Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Modern Psychological Studies by an authorized editor of UTC Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. An "Authentic Wholeness" Synthesis of Jungian and Existential Analysis Samuel Minier Wittenberg University Eclectic approaches to psychotherapy often lack cohesion due to the focus on technique and procedure rather than theory and wholeness of both the person and of the therapy. A synthesis of Jungian and existential therapies overcomes this trend by demonstrating how two theories may be meaningfully integrated The consolidation of the shared ideas among these theories reveals a notion of "authentic wholeness' that may be able to stand on its own as a therapeutic objective. Reviews of both analytical and existential psychology are given. Differences between the two are discussed, and possible reconciliation are offered. After noting common elements in these shared approaches to psychotherapy, a hypothetical therapy based in authentic wholeness is explored. Weaknesses and further possibilities conclude the proposal In the last thirty years, so-called "pop Van Dusen (1962) cautions that the differences among psychology" approaches to psychotherapy have existential theorists are vital to the understanding of effectively demonstrated the dangers of combining existentialism, that "[when] existential philosophy has disparate therapeutic elements. -

Npmarch-April12

THE NATIONAL Psychologist Vol. 21 No. 2 The Independent Newspaper for Practitioners March/April 2012 behavioral research and non-pharmacologi- Alzheimer’s plan emphasizes biology over behavior cal interventions, but it is still woefully inad- equate in many things such as the area of By Paula E. Hartman-Stein, Ph.D. that is open through March 30. Alzheimer’s Association barely acknowl- neuropsychological assessment, research NAPA established an advisory council edged mental health and non-pharmacologi- beyond biomarkers, the proposed public The most recent draft released Feb. 22 to develop an ambitious national plan with- cal interventions and made no mention of the education campaign addressing risk factors for a massive federal plan to address out waiting for Congress to act, and the most role of psychology in research, practice or and geriatric workforce funding.” Alzheimer’s disease is considered “woefully recent draft of the plan includes five goals diagnosing of Alzheimer’s. According to Michael Friedman, inadequate” in incorporating psychology and for preventing and effectively treating In response, APA CEO Norman B. LMSW, co-founder of the Geriatric Mental behavioral health into prevention and treat- Alzheimer’s by 2025, optimizing the quality Anderson, Ph.D., sent 13 pages of comments Health Alliance of New York, “The revised ment. The national plan stems from the and efficiency of care, expanding support for to HHS. He wrote, “It is surprising that there national plan acknowledges that mental National Alzheimer’s Project Act (NAPA) people with Alzheimer’s as well as their is no mention of the role of psychology in health problems occur in dementia, but the signed into law in January of last year. -

FRANCIS MARION UNIVERSITY DESCRIPTION of PROPOSED NEW COURSE Department/School H

FRANCIS MARION UNIVERSITY DESCRIPTION OF PROPOSED NEW COURSE Department/School HONORS Date September 16, 2013 Course No. or level HNRS 270-279 Title HONORS SPECIAL TOPICS IN THE BEHAVIORAL SCIENCES Semester hours 3 Clock hours: Lecture 3 Laboratory 0 Prerequisites Membership in FMU Honors, or permission of Honors Director Enrollment expectation 15 Indicate any course for which this course is a (an) Modification N/A Substitute N/A Alternate N/A Name of person preparing course description: Jon Tuttle Department Chairperson’s /Dean’s Signature _______________________________________ Date of Implementation Fall 2014 Date of School/Department approval: September 13, 2013 Catalog description: 270-279 SPECIAL TOPICS IN THE BEHAVIORAL SCIENCES (3) (Prerequisite: membership in FMU Honors or permission of Honors Director.) Course topics may be interdisciplinary and cover innovative, non-traditional topics within the Behavioral Sciences. May be taken for General Education credit as an Area 4: Humanities/Social Sciences elective. May be applied as elective credit in applicable major with permission of chair or dean. Purpose: 1. For Whom (generally?): FMU Honors students, also others students with permission of instructor and Honors Director 2. What should the course do for the student? HNRS 270-279 will offer FMU Honors members enhanced learning options within the Behavioral Sciences beyond the common undergraduate curriculum and engage potential majors with unique, non-traditional topics. Teaching method/textbook and materials planned: Lecture, -

7'Tie;T;E ~;&H ~ T,#T1tmftllsieotog

7'tie;T;e ~;&H ~ t,#t1tMftllSieotOg, UCLA VOLUME 3 1986 EDITORIAL BOARD Mark E. Forry Anne Rasmussen Daniel Atesh Sonneborn Jane Sugarman Elizabeth Tolbert The Pacific Review of Ethnomusicology is an annual publication of the UCLA Ethnomusicology Students Association and is funded in part by the UCLA Graduate Student Association. Single issues are available for $6.00 (individuals) or $8.00 (institutions). Please address correspondence to: Pacific Review of Ethnomusicology Department of Music Schoenberg Hall University of California Los Angeles, CA 90024 USA Standing orders and agencies receive a 20% discount. Subscribers residing outside the U.S.A., Canada, and Mexico, please add $2.00 per order. Orders are payable in US dollars. Copyright © 1986 by the Regents of the University of California VOLUME 3 1986 CONTENTS Articles Ethnomusicologists Vis-a-Vis the Fallacies of Contemporary Musical Life ........................................ Stephen Blum 1 Responses to Blum................. ....................................... 20 The Construction, Technique, and Image of the Central Javanese Rebab in Relation to its Role in the Gamelan ... ................... Colin Quigley 42 Research Models in Ethnomusicology Applied to the RadifPhenomenon in Iranian Classical Music........................ Hafez Modir 63 New Theory for Traditional Music in Banyumas, West Central Java ......... R. Anderson Sutton 79 An Ethnomusicological Index to The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, Part Two ............ Kenneth Culley 102 Review Irene V. Jackson. More Than Drumming: Essays on African and Afro-Latin American Music and Musicians ....................... Norman Weinstein 126 Briefly Noted Echology ..................................................................... 129 Contributors to this Issue From the Editors The third issue of the Pacific Review of Ethnomusicology continues the tradition of representing the diversity inherent in our field. -

As Writers of Film and Television and Members of the Writers Guild Of

July 20, 2021 As writers of film and television and members of the Writers Guild of America, East and Writers Guild of America West, we understand the critical importance of a union contract. We are proud to stand in support of the editorial staff at MSNBC who have chosen to organize with the Writers Guild of America, East. We welcome you to the Guild and the labor movement. We encourage everyone to vote YES in the upcoming election so you can get to the bargaining table to have a say in your future. We work in scripted television and film, including many projects produced by NBC Universal. Through our union membership we have been able to negotiate fair compensation, excellent benefits, and basic fairness at work—all of which are enshrined in our union contract. We are ready to support you in your effort to do the same. We’re all in this together. Vote Union YES! In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (THE DEUCE) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS) Daniel Abraham (THE EXPANSE) David Abramowitz (CAGNEY AND LACEY; HIGHLANDER; DAUGHTER OF THE STREETS) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; MR. BELVEDERE; THE PARKERS) Gayle Abrams (FASIER; GILMORE GIRLS; 8 SIMPLE RULES) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEEPER) Peter Ackerman (THINGS YOU SHOULDN'T SAY PAST MIDNIGHT; ICE AGE; THE AMERICANS) Joan Ackermann (ARLISS) 1 Ilunga Adell (SANFORD & SON; WATCH YOUR MOUTH; MY BROTHER & ME) Dayo Adesokan (SUPERSTORE; YOUNG & HUNGRY; DOWNWARD DOG) Jonathan Adler (THE TONIGHT SHOW STARRING JIMMY FALLON) Erik Agard (THE CHASE) Zaike Airey (SWEET TOOTH) Rory Albanese (THE DAILY SHOW WITH JON STEWART; THE NIGHTLY SHOW WITH LARRY WILMORE) Chris Albers (LATE NIGHT WITH CONAN O'BRIEN; BORGIA) Lisa Albert (MAD MEN; HALT AND CATCH FIRE; UNREAL) Jerome Albrecht (THE LOVE BOAT) Georgianna Aldaco (MIRACLE WORKERS) Robert Alden (STREETWALKIN') Richard Alfieri (SIX DANCE LESSONS IN SIX WEEKS) Stephanie Allain (DEAR WHITE PEOPLE) A.C. -

Volume 16 –Number 3 National Park Service • U.S

PARKARK P CIENCECIENCE SS Integrating Research and Resource Management Volume 16 –Number 3 National Park Service • U.S. Department of the Interior Summer 1996 THE NATURAL RESOURCE TRAINEE PROGRAM: PROFESSIONALIZATION TRIUMPH OF THE 1980S AND EARLY 1990S Who are they and where are they now? See the key on page 17 to identify these participants of the first Natural Resource Trainee Program and learn what they are up to now. BY THE EDITOR imparting the skills. Regional office funding allowed parks to HE NEED TO ESTABLISH AND PROFES- send staff to the training and backfill behind them to take care sionalize science and resource management func- of unfinished park work. Other superintendents soon heard tions and apply them in the management of na- about the training opportunity and wanted to be a part of it. tional parks was recognized as early as the 1930s. Wauer then prioritized individual park needs, opting for placing Then, biologist George Wright published several resource management trainees at parks that formerly didn’t have Tpapers on wildlife management and made the clear connection any resource management expertise. between science and informed park resource management ac- The program went national in the early 1980s following pub- tivities. Yet, for the next 5 decades, resource management work lication of two different conservation organization reports on continued to be done mostly by park rangers who were trained threats to national parks and a response by the National Park primarily in law enforcement and other operational areas, not Service in the form of a state-of-the-parks report. -

An Approach to Magnetic Cleanliness for the Psyche Mission M

An Approach to Magnetic Cleanliness for the Psyche Mission M. de Soria-Santacruz J. Ream K. Ascrizzi ([email protected]), ([email protected]), ([email protected]) M. Soriano R. Oran University of Michigan Ann Arbor ([email protected]), ([email protected]), 500 S State St O. Quintero B. P. Weiss Ann Arbor, MI 48109 ([email protected]), ([email protected]) F. Wong Department of Earth, Atmospheric, ([email protected]), and Planetary Sciences S. Hart Massachusetts Institute of Technology ([email protected]), 77 Massachusetts Avenue M. Kokorowski Cambridge, MA 02139 ([email protected]) B. Bone ([email protected]), B. Solish ([email protected]), D. Trofimov ([email protected]), E. Bradford ([email protected]), C. Raymond ([email protected]), P. Narvaez ([email protected]) Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology 4800 Oak Grove Drive Pasadena, CA 91109 C. Keys C. Russell L. Elkins-Tanton ([email protected]), ([email protected]), ([email protected]) P. Lord University of California Los Angeles Arizona State University ([email protected]) 405 Hilgard Avenue PO Box 871404 Maxar Technologies Inc. Los Angeles, CA 90095 Tempe, AZ 85287 3825 Fabian Avenue Palo Alto, CA 94303 Abstract— Psyche is a Discovery mission that will visit the fields. Limiting and characterizing spacecraft-generated asteroid (16) Psyche to determine if it is the metallic core of a magnetic fields is therefore essential to the mission. This is the once larger differentiated body or otherwise was formed from objective of the Psyche’s magnetics control program described accretion of unmelted metal-rich material. -

Existential and Humanistic Theories

Existential Theories 1 RUNNING HEAD: EXISTENTIAL THEORIES Existential and Humanistic Theories Paul T. P. Wong Graduate Program in Counselling Psychology Trinity Western University In Wong, P. T. P. (2005). Existential and humanistic theories. In J. C. Thomas, & D. L. Segal (Eds.), Comprehensive Handbook of Personality and Psychopathology (pp. 192-211). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Existential Theories 2 ABSTRACT This chapter presents the historical roots of existential and humanistic theories and then describes four specific theories: European existential-phenomenological psychology, Logotherapy and existential analysis, American existential psychology and American humanistic psychology. After examining these theories, the chapter presents a reformulated existential-humanistic theory, which focuses on goal-striving for meaning and fulfillment. This meaning-centered approach to personality incorporates both negative and positive existential givens and addresses four main themes: (a) Human nature and human condition, (b) Personal growth and actualization, (c) The dynamics and structure of personality based on existential givens, and (c) The human context and positive community. The chapter then reviews selected areas of meaning-oriented research and discusses the vital role of meaning in major domains of life. Existential Theories 3 EXISTENTIAL AND HUMANISTIC THEORIES Existential and humanistic theories are as varied as the progenitors associated with them. They are also separated by philosophical disagreements and cultural differences (Spinelli, 1989, 2001). Nevertheless, they all share some fundamental assumptions about human nature and human condition that set them apart from other theories of personality. The overarching assumption is that individuals have the freedom and courage to transcend existential givens and biological/environmental influences to create their own future. -

2. the Demonic in the Self

This PDF version is provided free of charge for personal and educational use, under the Creative Commons license with author’s permission. Commercial use requires a separate special permission. (cc) 2005 Frans Ilkka Mäyrä 2. The Demonic in the Self But ancient Violence longs to breed, new Violence comes when its fatal hour comes, the demon comes to take her toll – no war, no force, no prayer can hinder the midnight Fury stamped with parent Fury moving through the house. – Aeschylus, Agamemnon1 Demons were chasing me, trying to eat me. They were grotesque, surreal, and they just kept pursuing me wherever I went. I was fighting them with some kind of sword, hacking them to pieces. But each time I would cut one into small pieces, another would appear. – A dream of a patient; Stephen A. Diamond, Anger, Madness, and the Daimonic2 THE SELF The self is a problem. The long history of educated discussion about the human self has not succeeded in producing a consensus. Scholars working in the same discipline do not necessarily agree on the fundamentals when de- bating how a human being should be understood. This is even truer as we cross disciplinary boundaries. Some think it is not necessary to presume the existence of something like the “self,” others consider it more fruitful to ap- proach human existence from different levels of observation altogether. In the area of literature and literary studies, in psychology, as well as in other areas where individual experience is of paramount importance, the self nev- ertheless continues to raise interest.