Considering Joseph's Limited Formal Education, It Is Highly Unlikely He Invented the 188 Unique Names Found in the Book of Mo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Our World with One Step to the Side”: YALSA Teen's Top Ten Author

Shannon Hale “Our World with One Step to the Side”: YALSA Teen’s Top Ten Author Shannon Hale Talks about Her Fiction TAR: This quotation in the Salt Lake City Deseret News the workshopping experience is helpful because I would probably be of interest to inspiring creative learned to accept feedback on my own work, even writing majors: “Hale found the creative-writing if ultimately it didn’t take me where I want to go program at Montana to be very structured. ‘You get (it’s all for practice at that point!). As well, reading in a room with 15 people and they come at you and giving feedback on early drafts of other with razors. I became really tired of the death- people’s work was crucial for training me to be a oriented, drug-related, hopeless, minimalist, better editor of my own writing. existential terror stories people were writing.’” This What I don’t like (and I don’t think this is a seems to be the fashion in university creative writing program-specific problem) is the mob mentality programs, but it is contrary to the philosophy of that springs from a workshop-style setting. Any secondary English ed methods of teaching composi thing experimental, anything too different, is going tion classes (building a community of writers to get questioned or criticized. I found myself where the environment is trusting and risk-taking is changing what I wrote, trying to find what I encouraged as opposed to looking for a weakness thought would please my professors and col and attempting to draw blood). -

Princess Academy Teacher Guide.Indd

CLASSROOM DISCUSSION GUIDE Princess Academy by Shannon Hale 978-1-59990-073-5 ∙ PB $7.95 U.S./$9.00 Can. Fourteen-year-old Miri feels unimportant because she is not permitted to mine linder in the quarry alongside her father, her sister, and her peers on Mount Eskel. Instead, Miri is left to tend the goats, do housekeeping chores, and bargain with traders who carry goods from the lowlands to the mountain. When the Chief Delegate of Danland arrives on the moun- tain and announces that the priests of the creator god read the omens and divined Mount Eskel the home of the bride of the future king, the lives of all girls, ages twelve to seventeen, be- gin to change. Required to attend the princess academy that is governed by a stern teacher, Olana Mansdaughter, the girls learn both academics and social skills. Knowing the chosen bride’s family will have a good life, Miri is torn between being chosen by the prince and returning to her beloved home on Mount Eskel. Adventure, intrigue, and danger await the girls, and Miri has the opportunity to become group leader, rescuer, and friend. Princess Academy is a stimulating examination of the power of literacy and bigotry. The book explores such additional themes as heroism, courage, leadership, family and com- munity. Rich in purposeful setting, the book is an excellent conversation piece for discussing story structure and the writer’s craft. ABOUT THE AUTHOR Shannon Hale is the New York Times bestselling author of six young adult novels, including the Newbery Honor book Princess Academy and its sequel Palace of Stone (Au- gust 2012), two award-winning books for adults, and Mid- night in Austenland. -

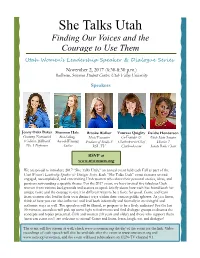

She Talks Utah Finding Our Voices and the Courage to Use Them

She Talks Utah Finding Our Voices and the Courage to Use Them Utah Women’s Leadership Speaker & Dialogue Series November 2, 2017 (6:30-8:30 p.m.) Ballroom, Sorensen Student Center, Utah Valley University Speakers Jenny Oaks Baker Shannon Hale Brooke Walker Vanessa Quigley Deidre Henderson Grammy Nominated Best-Selling, Host/Executive Co-Founder & Utah State Senator Violinist, Billboard Award-Winning Producer of Studio 5 Chatbooker-in-Chief District 7 No. 1 Performer Author KSL TV Chatbooks.com Senate Rules Chair RSVP at www.utwomen.org We are proud to introduce 2017 “She Talks Utah,” an annual event held each Fall as part of the Utah Women’s Leadership Speaker & Dialogue Series. Each “She Talks Utah” event features several engaged, accomplished, and entertaining Utah women who share their personal stories, ideas, and passions surrounding a specific theme. For the 2017 event, we have invited five fabulous Utah women from various backgrounds and sectors to speak briefly about how each has found both her unique voice and the courage to use it in different ways to be a force for good. Come and learn from women who lead in their own distinct ways within their various public spheres. As you listen, think of how you can also influence and lead both informally and formally in meaningful and authentic ways as well. The speeches will be filmed, so prepare to be a lively audience! For the last 30 minutes, attendees will pick up some light refreshments and find dialogue groups to discuss the concepts and topics presented. Girls and women (10 years and older) and those who support them (men can come too!) are welcome to attend! Come and listen, learn, laugh, eat, and dialogue! The event will live stream as well; check www.utwomen.org the day of the event for the link. -

Curriculum Vitae

Shannon Hale www.shannonhale.com @haleshannon PROFILE Best-selling, award-winning author of over thirty books for early readers, middle grade readers, young adults, and adults, translated into twenty-five languages and studied in classrooms from elementary schools to universities EDUCATION University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah — B.A. English, 1998 University of Montana, Missoula, Montana —M.F.A. Creative Writing, 2000 BOOKS The Goose Girl, Bloomsbury — 2003 Josette Frank Award, ALA Teen Top Ten, Texas Lone Star Book, Utah Children’s Book Award, Humpty Dumpty Chapter Book Award, NPR 100 Best-Ever Teen Novel Enna Burning, Bloomsbury — 2004 ALM Young Adult Fiction Award, New York Library Book for the Teen Age, Association of Booksellers for Children “Best Book” Princess Academy, Bloomsbury — 2005 Newbery Honor Award winner, New York Times best seller, Publisher’s Weekly best seller, Book Sense Pick, ALA Notable Children’s Book, Beehive Award, Utah Children’s Book Award, a New York Public Library Book for the Teen Age selection, a Bank Street College Best Children’s Books of the Year (starred entry), a YALSA Popular Paperback for Young Adults, on seven state awards lists River Secrets, Bloomsbury — 2006 ALA Teen Top Ten, Booklist Top 10 Fantasy Book for Youth, YALSA Popular Paperback for Young Adults, four professional starred reviews Book of a Thousand Days, Bloomsbury — 2007 ALA Best Book for Young Adults, winner of the Cybils Award for best Young Adult Science Fiction and Fantasy Novel of the Year, A School Library Journal Best Book -

Letter from the Chair Symposium Committee

Letter from the Chair Hello and welcome to another year of LTUE! Every year While I am the head of this year’s event, I am only one at LTUE, we strive to bring you an amazing experience of of many, many people who make this possible each year. learning about creating science fiction and fantasy, and I I would first like to thank our panelists. You are the ones am excited to be presenting to you this year’s rendition! who come and share your knowledge and insights with us. We as a committee have been working hard all year to Without you there would be no symposium, no point in our make it an excellent symposium for you, and I hope coming! Second, I would like to profusely thank our com- that you find something (or many somethings) that you mittee members and volunteers. You are the ones who put enjoy. If you are new to the symposium, welcome and everything together throughout the year and make things come discover something amazing! If you are returning, run smoothly through our three intense days together. welcome back and I hope you build on what you learned Third, I would like to thank all of our attendees. You are in the past. why we all do the work to create this amazing symposium! For me, LTUE has been a great land of discovery. I have Enjoy your time here, whatever your role may be. Find learned how to do many things. I have learned about something to take with you when you leave, and try to myself as a creator. -

Princess Academy That Is Governed by a Stern Teacher, Olana Mansdaughter, the Girls Learn Both Academics and Social Skills

Teacher’s Guide Princess Acadamy by Shannon Hale **These notes may be reproduced free of charge for use and study within schools, but they may not be reproduced (either in whole or in part) and offered for commercial sale** SYNOPSIS Fourteen-year-old Miri feels unimportant because she is not permitted to mine linder in the quarry alongside her father, her sister, and her peers on Mount Eskel. Instead, Miri is left to tend the goats, do housekeeping chores, and bargain with traders who carry goods from the lowlands to the mountain. When the Chief Delegate of Danland arrives on the mountain and announces that the priests of the creator god read the future king, the lives of all girls, ages twelve to seventeen, begin to change. Required to attend the princess academy that is governed by a stern teacher, Olana Mansdaughter, the girls learn both academics and social skills. Knowing the chosen bride’s family will have a good life, Miri is torn between being chosen by the prince and returning to her beloved home on Mount Eskel. Adventure, intrigue, and danger await the girls, and Miri has the opportunity to become group leader, rescuer, and friend. Princess Academy is a stimulating examination of the power of literacy and bigotry. The book explores such additional themes as heroism, courage, leadership, family and community. Rich in purposeful setting, the book is an excellent conversation piece for discussing story structure and the writer’s craft. ABOUT THE AUTHOR Shannon Hale is the New York Times bestselling author of six young adult novels, including the Newbery Honor book Princess Academy and its sequel Palace of Stone (August 2012), two award-winning books for adults, and Midnight in Austenland. -

Princess Academy

Princess Academy What would you do if all the girls in your village had to attend an academy to become the future princess? This is what happens to Miri. She is thrust into a new life without any say because the prince is suppose to pick his princess from Miri’s village. Come along with Miri on her journey through the princess academy. Shannon Hale lives close to Salt Lake City, Utah. She started writing when she was nine years old and she has been writing ever since. Her first book was The Goose Girl. She has received many awards for her different novels. One of her adult novels even became a movie! Pre-Reading Activities Post-Reading Activities 1. Make a curriculum that you think would be 1. After reading the story make a brochure used at a princess academy. about Miri’s village to get people to visit. 2. Separate into groups and each group read a 2. Set up a trading center and let students barter princess story. for their supplies. Related Books Princess Academy: Palace of Stone by Shannon Hale Princess Academy: The Forgotten Sister by Shannon Hale Fairest by Gale Carson Levine Discussion Questions 1. Miri’s father tells her the story of how she got her name. Find the meaning of your name. Do you know why that name was special to your parents? 2. Does Princess Academy remind you of another novel? If so, what novel? 3. How did you feel about Prince Steffen’s final choice? 4. Miri and the other girls range in age from twelve to eighteen. -

GRAPHIC NOVELS Real Friends by Shannon Hale, Illustrated By

CPL Librarian Emily’s 2017 Upper School Book Recs! GRAPHIC NOVELS Real Friends by Shannon Hale, illustrated by LeUyen Pham Memoir-style like Raina Telgemeier’s books, this book is by the author of the Princess Academy books and the Ever After High series. Shannon portrays her experience in middle school when her best friend Adrienne became friends with Jen, the leader of the popular girls. Shannon doesn’t know if Jen likes her, she doesn’t know if Adrienne still likes her, and she isn’t sure she even wants to be part of the popular group. Great comic about bullies, losing friends, gaining friends, and finding out who you are. Goldie Vance by Hope Larson, illustrated by Britney Williams Goldie is a sassy, awesome, Nancy Drew-type detective who lives at a Florida resort with her dad. She’s super smart, is an awesome drag car racer, and has a great crew of friends, including her cute actress crush, who help her solve mysteries. The Adventures of John Blake by Philip Pullman, illustrated by Fred Fordham This book is by the author of The Golden Compass (His Dark Materials series) and has a little bit of everything: an evil billionaire trying to take over the world, cool new technology, time travel, pirates, daring rescues at sea, and a teen named John Blake who knows a dangerous secret. Shattered Warrior by Sharon Shinn, illustrated by Molly Knox Ostertag An Earth-like planet has been invaded and colonized by aliens, called the Derichets. They have enslaved the humans native to that planet to mine for them. -

20S Macm Kids Add-Ons

20S Macm Kids Add-ons Bleak House by G. A. Henty and Charles Dickens Author Bio Considered by many to be the greatest novelist of the English language, Charles John Huffam Dickens was born February 7, 1812, in Portsmouth, England. Some of his most popular works include Oliver Twist, David Copperfield, Nicholas Nickleby, A Tale of Two Citiesand Great Expectations Alma Books On Sale: Aug 18/20 5.04 x 7.8 • 992 pages line illustrations 9781847496713 • $13.50 • pb Fiction / Classics • Ages 9-11 years Series: Evergreens Notes Promotion Page 1 of 21 20S Macm Kids Add-ons Dark Skies by Danielle L. Jensen Unwanted betrothals, assassination attempts, and a battle for the crown converge in Danielle L. Jensen's Dark Skies , a new series starter set in the universe of the YA fantasy Sarah J. Maas called everything I look for in a fantasy novel." A RUNAWAY WITH A HIDDEN PAST Lydia is a scholar, but books are her downfall when she meddles in the plots of the most powerful man in the Celendor Empire. Her life in danger, she flees west to the far side of the Endless Seas and finds herself entangled in a foreign war where her burgeoning powers are sought by both sides. A COMMANDER IN DISGRACE Killian is Marked by the God of War, but his gifts fail him when the realm under the dominion of the Corrupter invades Mudamora. Disgraced, he swears his sword to the kingdom's only hope: the crown princess. But the choice sees him caught up in a web of political intrigue that will put his oath - and his heart - to the test. -

Annual Meeting Handbook Advertiser S 2011 Annual Meeting Sponsor 13

Cascadilla Press LINGUISTIC SOCIETY OF AMERICA MEETING HANDBOOK 2011 AMERICA OF LINGUISTIC SOCIETY New for 2011! Online delivery! Wyndham Grand Pittsburgh Downtown Pittsburgh, PA Surviving Linguistics: A Guide for Arboreal for Mac or Windows 6-9 January 2011 Graduate Students Second Edition With Arboreal you’ll find it easy to create syntax trees right Monica Macaulay in your word processor. Arboreal is a TrueType font which gives you branching lines, triangles, and movement lines. Surviving Linguistics offers linguistics students clear and You can put the text of the tree in any font you like, and use practical advice on how to succeed in graduate school and Arboreal to do the rest. Arboreal works with any Mac or earn a degree. The book is a valuable resource for students Windows application. at any stage of their graduate career, from learning to write linguistics papers through completing their dissertation We’ve come a long way from floppy disks. You can now and finding a job. Along the way, Macaulay explains the buy Arboreal or ArborWin through Kagi. They’ll email you Meeting Handbook process of submitting conference abstracts, speaking at a personal download link—click on the link, install the conferences, writing grant applications, publishing journal font, and you’ll be making beautiful articles, creating a CV, and much more. trees in minutes. The second edition adds a new section for undergraduates Arboreal for Mac Linguistic Society of America applying to grad school in linguistics, more information on $20.00 CD-ROM or download funding sources, preparing conference posters, and citation Arboreal for Windows (ArborWin) managers, and new book and website recommendations. -

Bibliomaniacs

THE 1511 South 1500 East Salt Lake City, UT 84105 801-484-9100 Inkslinger2009 Holiday Edition MatchMaker, MatchMaker: a holiday chorus in Books The collective voice of The King’s English booksellers In this season of thanks and gift-giving…Whether it’s a $12 no-frills paperback or a lavishly illustrated $200 hardcover, a book is, dollar for dollar, the best possible present for people of all ages and stages of life. Why? Because there is one particular book that is perfect for practically everyone. The booksellers at TKE know this because it’s our daily preoccupa- tion, this occupation that allows us the bliss of matching books to people. So scroll through this cast of characters we’ve come to know and love until you spot your own friends and family members. You’ll find the perfect book(s) to match their passions listed by category. CAST OF CHARACTERS, READERS ALL: l Bibliomaniacs Bibliomaniacs Magnus Opus For the collectors among us who value the value of books or who love Outliers particular writers with passion, a signed first edition is a treasure be- True Believers yond measure, a gift never to be forgotten. Margaret Atwood’s Year of the Flood, Sherman Alexie’s War Dances, and Richard Russo’s That Old Excellent Women Cape Magic gleam on our shelves, signed firsts Sons and Lovers one and all, waiting for homes in the libraries of our bibliophilic friends. And what better gift Naturalists for the women who loved The Time Traveler’s Photographers Wife than a chance to meet Audrey Niffenegger Artists Within and get a first edition of Her Fearful Symmetry personalized? Wrap up a first edition now, and Writers and Readers we’ll include a ticket for Niffenegger’s January Detectives of the Mysterious 20th appearance at TKE. -

REVIEWS a Survey of Mainstream Children's Books by LDS Authors. Reviewed by Stacy Whitman, an Editor at Mirrorstone, Which

REVIEWS A Survey of Mainstream Children’s Books by LDS Authors. Reviewed by Stacy Whitman, an editor at Mirrorstone, which publishes fantasy for children and young adults. She holds a master’s degree in children’s literature from Simmons College. A slightly modified version of this review was posted on By Common Consent, December 20, 2007 {http://www.bycommonconsent. com}. If you’re at all familiar with literary talk these days, you might be aware of the chatter about children’s and young adult literature1 being the hot new thing. Everyone’s wondering what will be the “next Harry Potter.” What was once a ghettoized field of study—because children are a self-perpetuat- ing lower class, and literature for children must therefore serve a purpose (teach a lesson or make kids get good grades)—is now legitimate at many institutes of higher learning. Adults are getting reading recommendations from children and teens, and vice versa. Despite frenzied reports to the contrary, reading is not dead among the younger set. When people ask what I do for a living, invariably the reaction to my answer—that I’m a children’s book editor—is “how exciting!”—espe- cially when I say that I edit children’s and young adult fantasy novels. It is exciting. We’re living in a golden age of children’s and young adult litera- ture, full of breathtaking storytelling and artistry. And some of the leading names in this golden age are authors who happen to be Mormons. When I read submissions at work, any variation on “the moral of this story is .