Ajmer- Banaras-Pandharpur*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Narrating North Gujarat: a Study of Amrut Patel's

NARRATING NORTH GUJARAT: A STUDY OF AMRUT PATEL’S CONTRIBUTION TO FOLK LITERATURE A MINOR RESEARCH PROJECT :: SUBMITTED TO :: UNIVERSITY GRANTS COMMISSION :: SUBMITTED BY :: DR.RAJESHKUMAR A. PATEL ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR SMT.R.R.H.PATEL MAHILA ARTS COLLEGE, VIJAPUR DIST.MEHSANA (GUJARAT) 2015 Preface Literature reflects human emotions, thoughts and expressions. It’s a record of activities and abstract ideas of human beings. The oral tradition of literature is the aspect of literature passing ideas and feelings mouth to mouth. I’ve enjoyed going through the precious and rare pieces of folk literature collected and edited by Amrut Patel. I congratulate and salute Amrut Patel for rendering valuable service to this untouchable, vanishing field of civilization. His efforts to preserve the vanishing forms of oral tradition stand as milestone for future generation and students of folk literature. I am indebted to UGC for sanctioning the project. The principal of my college, Dr.Sureshbhai Patel and collegues have inspired me morally and intellectually. I thank them. I feel gratitude to Nanabhai Nadoda for uploding my ideas and making my work easy. Shaileshbhai Paramar, the librarian has extended his time and help, I thank him. Shri Vishnubhai M.Patel, Shri R.R.Ravat, Shri.D.N.Patel, Shri S.M.Patel, Shri R.J.Brahmbhatt, Shri J.J.Rathod., Shri D.S.Kharadi, B.L.Bhangi and Maheshbhai Limbachiya have suppoted me morally. I thank them all. DR.Rajeshkumar A.Patel CONTENTS 1. Introduction: 1.1 North Gujarat 1.2 Life and Works of Dr.Amrut Patel 1.3 Folk Literature-An Overview 2. -

District Taluka Center Name Contact Person Address Phone No Mobile No

District Taluka Center Name Contact Person Address Phone No Mobile No Mhosba Gate , Karjat Tal Karjat Dist AHMEDNAGAR KARJAT Vijay Computer Education Satish Sapkal 9421557122 9421557122 Ahmednagar 7285, URBAN BANK ROAD, AHMEDNAGAR NAGAR Anukul Computers Sunita Londhe 0241-2341070 9970415929 AHMEDNAGAR 414 001. Satyam Computer Behind Idea Offcie Miri AHMEDNAGAR SHEVGAON Satyam Computers Sandeep Jadhav 9881081075 9270967055 Road (College Road) Shevgaon Behind Khedkar Hospital, Pathardi AHMEDNAGAR PATHARDI Dot com computers Kishor Karad 02428-221101 9850351356 Pincode 414102 Gayatri computer OPP.SBI ,PARNER-SUPA ROAD,AT/POST- 02488-221177 AHMEDNAGAR PARNER Indrajit Deshmukh 9404042045 institute PARNER,TAL-PARNER, DIST-AHMEDNAGR /221277/9922007702 Shop no.8, Orange corner, college road AHMEDNAGAR SANGAMNER Dhananjay computer Swapnil Waghchaure Sangamner, Dist- 02425-220704 9850528920 Ahmednagar. Pin- 422605 Near S.T. Stand,4,First Floor Nagarpalika Shopping Center,New Nagar Road, 02425-226981/82 AHMEDNAGAR SANGAMNER Shubham Computers Yogesh Bhagwat 9822069547 Sangamner, Tal. Sangamner, Dist /7588025925 Ahmednagar Opposite OLD Nagarpalika AHMEDNAGAR KOPARGAON Cybernet Systems Shrikant Joshi 02423-222366 / 223566 9763715766 Building,Kopargaon – 423601 Near Bus Stand, Behind Hotel Prashant, AHMEDNAGAR AKOLE Media Infotech Sudhir Fargade 02424-222200 7387112323 Akole, Tal Akole Dist Ahmadnagar K V Road ,Near Anupam photo studio W 02422-226933 / AHMEDNAGAR SHRIRAMPUR Manik Computers Sachin SONI 9763715750 NO 6 ,Shrirampur 9850031828 HI-TECH Computer -

Sadhanayatra

SADHANA YATRA December 23, 2012~ January 1o, 2013 {option to start on December 27, 2012} {optional extension January 11 - 12, 2013} JOIN NĀMARŪPA & FRIENDS ON A PILGRIMAGE TO INDIA Chennai Beach Resort ~ Tiruvannamalai Retreat with Swamijis from Himalayas Chidambaram Festival ~ Puducherry ~ Kanchipuram ~ Tirupati ~ Govardhan Eco ~ Village Retreat ~ Ashta Vinayaka ~ Pandharpur ~ Trimbakeshwar ~ Mumbai Sunday December 23, 2012 ~ Chennai MGM Beach Resort Prithivi (earth) lingam and Varadharaja Perumal (Lord Vishnu). Arrive in Chennai no later than the night of December 22 or early Tuesday January 1, 2013 ~ Tirupati morning on December 23. Check into MGM Beach Resort. Relax. Depart for Sri Kalahasthi and darshan of Vayu (air) Lingam, and then Meet the group & discuss the Yatra, daily programs, & local customs. on to Tirupati. Monday December 24 ~ Tiruvannamalai Retreat Wednesday January 2 ~ Tirupati After a late morning's rest we will travel through the beautiful South Climb 4000 steps in 4 hours (optional travel by bus) to have darshan Indian rice paddies and ancient boulder formations to the temple of Lord Venkateswara (Balaji). We will take the bus back down! town of Tiruvannamalai and check into the Sparsha Eco-Resort. Thursday January 3 ~ Fly to Mumbai ~ Govardhan Eco Village Tuesday December 25 ~ Tiruvannamalai Retreat A short flight north to Mumbai and then on to the Govardhan Eco During our stay here we will gather together for informal discussions Village for a Bhakti Retreat. with Swamijis from the Himalayas. The swamis are specially gather- Friday January 4 ~ Govardhan Eco Village ing here to greet and talk with us. We will also go for darshan of the Take a well earned rest in the quiet natural setting of the Sahyadri Agni (fire) lingam in the great temple of Arunachaleswara and climb mountains. -

Ecosystem : an Ecosystem Is a Complete Community of Living Organisms and the Nonliving Materials of Their Surroundings

Solapur: Introduction: Solapur District is a district in Maharashtra state of India. The city of Solapur is the district headquarters. It is located on the south east edge of the state and lies entirely in the Bhima and Seena basins. Facts District - Solapur Area - 14886 km² Sub-divisions - Solapur, Madha (Kurduwadi), Pandharpur Talukas - North Solapur, Barshi, Akkalkot, South Solapur, Mohol,Mangalvedha, Pandharpur, Sangola, Malshiras, Karmala, Madha. Proposal for a separate Phandarpur District The Solapur district is under proposal to be bifurcated and a separate Phandarpur district be carved out of existing Solapur district. Distance from Mumbai - 450 km Means of transport - Railway stations -Solapur, Mohol, Kurduwadi, Madha, Akkalkot Road ST Buses, SMT (Solapur Municipal Transportation, Auto- Rikshaws. Solapur station has daily train service to Mumbai via Pune known as Siddheshwar Express Also, daily shuttle from Solapur to Pune known as Hutatma Express Population Total - 3,849,543(District) The district is 31.83% urban as of 2001. Area under irrigation - 4,839.15 km² Irrigation projects Major-1 Medium-2 Minor-69 Imp. Projs.- Bhima Ujjani Industries Big-98 Small-8986 Languages/dialects - Marathi, Kannada, Telagu Folk-Arts - Lavani, Gondhal, Dhangari,Aradhi and Bhalari songs Weather Temperature Max: 44.10 °C Min: 10.7 °C Rainfall-759.80 mm (Average) Main crops - Jowar, wheat, sugarcane Solapur district especially Mangalwedha taluka is known for Jowar. Maldandi Jowar is famous in all over Maharashtra. In December - January agriculturists celebrates Hurda Party. This is also famous event in Solapur. Hurda means pre-stage of Jowar. Agriculturists sow special breed of Hurda, named as Dudhmogra, Gulbhendi etc. -

Bhoga-Bhaagya-Yogyata Lakshmi

BHOGA-BHAAGYA-YOGYATA LAKSHMI ( FULFILLMENT AS ONE DESERVES) Edited, compiled, and translated by VDN Rao, Retd. General Manager, India Trade Promotion Organization, Ministry of Commerce, Govt. of India, Pragati Maidan, New Delhi, currently at Chennai 1 Other Scripts by the same Author: Essence of Puranas:-Maha Bhagavata, Vishnu Purana, Matsya Purana, Varaha Purana, Kurma Purana, Vamana Purana, Narada Purana, Padma Purana; Shiva Purana, Linga Purana, Skanda Purana, Markandeya Purana, Devi Bhagavata;Brahma Purana, Brahma Vaivarta Purana, Agni Purana, Bhavishya Purana, Nilamata Purana; Shri Kamakshi Vilasa Dwadasha Divya Sahasranaama: a) Devi Chaturvidha Sahasra naama: Lakshmi, Lalitha, Saraswati, Gayatri; b) Chaturvidha Shiva Sahasra naama-Linga-Shiva-Brahma Puranas and Maha Bhagavata; c) Trividha Vishnu and Yugala Radha-Krishna Sahasra naama-Padma-Skanda-Maha Bharata and Narada Purana. Stotra Kavacha- A Shield of Prayers Purana Saaraamsha; Select Stories from Puranas Essence of Dharma Sindhu Essence of Shiva Sahasra Lingarchana Essence of Paraashara Smtiti Essence of Pradhana Tirtha Mahima Dharma Bindu Essence of Upanishads : Brihadaranyaka , Katha, Tittiriya, Isha, Svetashwara of Yajur Veda- Chhandogya and Kena of Saama Veda-Atreya and Kausheetaki of Rig Veda-Mundaka, Mandukya and Prashna of Atharva Veda ; Also ‘Upanishad Saaraamsa’ (Quintessence of Upanishads) Essence of Virat Parva of Maha Bharata Essence of Bharat Yatra Smriti Essence of Brahma Sutras Essence of Sankhya Parijnaana- Also Essence of Knowledge of Numbers Essence of Narada Charitra; Essence Neeti Chandrika-Essence of Hindu Festivals and Austerities- Essence of Manu Smriti*- Quintessence of Manu Smriti* - *Essence of Pratyaksha Bhaskara- Essence of Maha Narayanopanishad*-Essence of Vidya-Vigjnaana-Vaak Devi* Note: All the above Scriptures already released on www. -

The Color Festival of Bikaner, Rajasthan

1 Prof. Amarika Singh Vice Chancellor Mohanlal Sukhadia University Udaipur, Rajasthan, India No.PSVC/MLSU/Message/2021 Dated 8th June, 2021 MESSAGE I am glad to know that the Department of History, Mohanlal Sukhadia University, Udaipur, in collaboration with Indus International Research Foundation, New Delhi, is organizing an Intemational Webinar on "Holi : A Custodian of Vibrant Indian Values and Culture" on 11 th and 12 th June 2021, and an E-Souvenir will be released on this occasion. I hope that the deliberation of the Webinar will help in revealing unique traditions of celebrating Holi Festival in India and by Indians living abroad. I wish the Webinar a grand success. (Prof. Amarika Singh) Vice Chancellor 2 Col. (Dr.) Vijaykant Chenji President Indus International Research Foundation New Delhi, India Dated 8th June, 2021 MESSAGE India is a multicultural nation with rich traditions and customs. Inspite of its diversity there is a common thread that runs through its multilingual, multi ethnic societies, connecting them to form a beautiful necklace. The festivals of India are celebrated each year with great deal of enthusiasm and fervour. These are associated with change of seasons and bring freshness and vibrancy to our spirit of life. One such event is Holi, the festival of colours. It is normally celebrated on the full moon day of March. Although Holi celbrated in Rajasthan, Mathura, Awadh and Varanasi are internationally known, Holi is also celebrated across other parts of India in the West, South and East too. They are known by different names and modus of celebrations vary. But at the heart, the theme remains the same - Triumph of Right over evil. -

Srirangam – Heaven on Earth

Srirangam – Heaven on Earth A Guide to Heaven – The past and present of Srirangam Pradeep Chakravarthy 3/1/2010 For the Tag Heritage Lecture Series 1 ARCHIVAL PICTURES IN THE PRESENTATION © COLLEGE OF ARTS, OTHER IMAGES © THE AUTHOR 2 Narada! How can I speak of the greatness of Srirangam? Fourteen divine years are not enough for me to say and for you to listen Yama’s predicament is worse than mine! He has no kingdom to rule over! All mortals go to Srirangam and have their sins expiated And the devas? They too go to Srirangam to be born as mortals! Shiva to Narada in the Sriranga Mahatmaya Introduction Great civilizations have been created and sustained around river systems across the world. India is no exception and in the Tamil country amongst the most famous rivers, Kaveri (among the seven sacred rivers of India) has been the source of wealth for several dynasties that rose and fell along her banks. Affectionately called Ponni, alluding to Pon being gold, the Kaveri river flows in Tamil Nadu for approx. 445 Kilometers out of its 765 Kilometers. Ancient poets have extolled her beauty and compared her to a woman who wears many fine jewels. If these jewels are the prosperous settlements on her banks, the island of Srirangam 500 acres and 13 kilometers long and 7 kilometers at its widest must be her crest jewel. Everything about Srirangam is massive – it is at 156 acres (perimeter of 10,710 feet) the largest Hindu temple complex in worship after Angkor which is now a Buddhist temple. -

Evaluation of Infrastructure Facilities and Perception of Pilgrims at Palitana

International Journal of Applied Research 2021; 7(3): 284-289 ISSN Print: 2394-7500 ISSN Online: 2394-5869 Impact Factor: 8.4 Evaluation of infrastructure facilities and perception IJAR 2021; 7(3): 284-289 of pilgrims at Palitana www.allresearchjournal.com Received: 12-01-2021 Accepted: 14-02-2021 Tanmay Choksi and Anand Kapadia Tanmay Choksi M. Plan Student, Department Abstract of Architecture, Master of Background and Objective: Religious tourism seems to be one of the most preferred tourism after Urban and Regional Planning, business tourism in Gujarat. Palitana is one of the very important pilgrimage destination among six G.C Patel Institute of religious sites in Gujarat. The main objective of this study was to assess the existing infrastructure and Architecture, interior designing institutional framework for tourism in Palitana town and identify the gaps as well as to study perception and Fine Arts, Veer Narmad South Gujarat University, of pilgrims at Palitana. Surat, Gujarat, India Methodology: Data collection was done in two phases. Primary data collection was done by using 16 item questionnaire was used to evaluate tourist perception. 100 tourists were evaluated by convenience Anand Kapadia sampling. Secondary data collection was done from the existing review of literature and various Associate Professor, government sources to find out the existing infrastructure facilities. Road network, transport facility, Department of Architecture, water supply, Sewerage and solid waste management, accommodation facilities, recreational facilities Master of Urban and Regional and tourist inflow were included in secondary data collection. Planning, G.C Patel institute Results and data analysis: 79% of tourists’ purpose was purely religious and they all were Jains. -

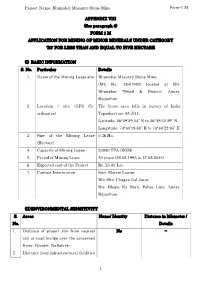

Bhunabai Masonry Stone Mine Form-1 M APPENDIX VIII

Project Name: Bhunabai Masonry Stone Mine Form-1 M APPENDIX VIII (See paragraph 6) FORM 1 M APPLICATION FOR MINING OF MINOR MINERALS UNDER CATEGORY ‘B2’ FOR LESS THAN AND EQUAL TO FIVE HECTARE (I) BASIC INFORMATION S. No. Particular Details 1. Name of the Mining Lease site Bhunabai Masonry Stone Mine (ML No.: 284/1992) located at N/v: Bhunabai, Tehsil & District: Ajmer, Rajasthan 2. Location / site (GPS Co- The lease area falls in survey of India ordinates) Toposheet no. 45 J/11. Latitude: 26°29’29.54” N to 26°29’32.29” N Longitude: 74°40’19.88” E to 74°40’22.93” E 3. Size of the Mining Lease 0.36 Ha. (Hectare) 4. Capacity of Mining Lease 20920 TPA (ROM) 5. Period of Mining Lease 50 years (28.08.1993 to 27.08.2043) 6. Expected cost of the Project Rs. 25.00 Lac 7. Contact Information Smt. Marrie Louise W/o Shri Chagan Lal Jatav R/o: Bhopo Ka Bara, Police Line, Ajmer, Rajasthan (II) ENVIRONMENTAL SENSITIVITY S. Areas Name/ Identity Distance in kilometer / No. Details 1. Distance of project site from nearest No -- rail or road bridge over the concerned River, Rivulet, Nallah etc. 2. Distance from infrastructural facilities 1 Project Name: Bhunabai Masonry Stone Mine Form-1 M Railway line Ajmer Railway ~5.15 Km towards SW Junction National Highway NH-08 ~3.4 Km towards E NH-79 ~5.0 Km towards SW State Highway -- -- Major District Road -- -- Any Other Road -- -- Electric transmission line pole or -- -- tower Canal or check dam or reservoirs or -- -- lake or ponds In-take for drinking water pump -- -- house Intake for Irrigation canal pumps -- -- 3. -

Lake Anasagar, Ajmer, Rajasthan, India

Evidence‐Based Holistic Restoration of Lake Anasagar, Ajmer, Rajasthan, India Deep Narayan Pandey1*, Brij Gopal2, K. C. Sharma3 1 Member Secretary, Rajasthan State Pollution Control Board, Jaipur – 302015; Email: [email protected] 2 Ex-Professor, Jawahar Lal Nehru University, New Delhi, currently at Centre for Inland Waters in South Asia, National Institute of Ecology, Jaipur, Rajasthan 302017; Email: [email protected] 3 Professor and Head, Department of Environmental Science Central University of Rajasthan, NH-8 Bandarsidri, Kishangarh – 305801 Ajmer, Rajasthan, Email: [email protected] Views expressed in this paper are those of the authors; they do not necessarily represent the views of RSPCB or the institutions to which authors belong. Rajasthan State Pollution Control Board 4-Jhalana Institutional Area Jaipur 302 004, Rajasthan, India www.rpcb.nic.in 1 CONTENTS 1. Introduction 3 2. Present status of Lake Anasagar 3 3. Multiple stressors degrading the Lake Anasagar 4 3.1. Disposal of raw sewage and municipal wastewater 5 3.2. Discharge of detergents 6 3.3. Discharge of residual pesticides and fertilizers 7 3.4. Sedimentation due to soil erosion 7 3.5. Challenges of land ownership and encroachment 8 4. Holistic restoration of Lake Anasagar 8 4.1. Waste and sewage management 9 4.2. Forest restoration in the watershed 11 4.3. Sequential restoration of vegetation in sand dunes 12 4.4. Management of urban green infrastructure 13 4.5. Periodic sediment removal from lake 14 4.6. Macrophyte restoration in littoral zone of lake 15 4.7. Recovery of costs and reinvestment in urban systems 16 4.8. -

3.Hindu Websites Sorted Country Wise

Hindu Websites sorted Country wise Sl. Reference Country Broad catergory Website Address Description No. 1 Afghanistan Dynasty http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hindushahi Hindu Shahi Dynasty Afghanistan, Pakistan 2 Afghanistan Dynasty http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jayapala King Jayapala -Hindu Shahi Dynasty Afghanistan, Pakistan 3 Afghanistan Dynasty http://www.afghanhindu.com/history.asp The Hindu Shahi Dynasty (870 C.E. - 1015 C.E.) 4 Afghanistan History http://hindutemples- Hindu Roots of Afghanistan whthappendtothem.blogspot.com/ (Gandhar pradesh) 5 Afghanistan History http://www.hindunet.org/hindu_history/mode Hindu Kush rn/hindu_kush.html 6 Afghanistan Information http://afghanhindu.wordpress.com/ Afghan Hindus 7 Afghanistan Information http://afghanhindusandsikhs.yuku.com/ Hindus of Afaganistan 8 Afghanistan Information http://www.afghanhindu.com/vedic.asp Afghanistan and It's Vedic Culture 9 Afghanistan Information http://www.afghanhindu.de.vu/ Hindus of Afaganistan 10 Afghanistan Organisation http://www.afghanhindu.info/ Afghan Hindus 11 Afghanistan Organisation http://www.asamai.com/ Afghan Hindu Asociation 12 Afghanistan Temple http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hindu_Temples_ Hindu Temples of Kabul of_Kabul 13 Afghanistan Temples Database http://www.athithy.com/index.php?module=p Hindu Temples of Afaganistan luspoints&id=851&action=pluspoint&title=H indu%20Temples%20in%20Afghanistan%20. html 14 Argentina Ayurveda http://www.augurhostel.com/ Augur Hostel Yoga & Ayurveda 15 Argentina Festival http://www.indembarg.org.ar/en/ Festival of -

Magazine1-4 Final.Qxd (Page 2)

SUNDAY, MARCH 28, 2021 INTERNET EDITION : www.dailyexcelsior.com/sunday-magazine apply any colour of his choice on Radha's face. This festival is celebrated remembering this incident, and the divine love between Radha and Krishna. Shri Krishna popularized the festival in Braj where he applied colour on Radha and the gopis using water jets called pichkaris. HOLI CELEBRATIONS The celebrations gained acceptance and popularity. Slowly, the use of col- ors and pichkaris in Holi became rampant. This pastime is wonderfully brought alive each year all over India. In fact, the entire country is drenched in coloured water for Holi. On the day of Holi, people enjoy throwing colours on each other. People play Holi with great elation and spray coloured water A worldwide festival Now everywhere. People usually wear white garments on this day. Many sweets are prepared and exchanged. Traditionally, Holi colours were derived from natural sources and are either particulate powders or liquid splashes. In ancient times, when people started playing Holi, the colours used by them were made from plants like Neem, Haldi, Bilva, Palash etc. The colours with which Holi is celebrated denotes the various facets of life, moods, emotions, situations, attachments and aversions, spiritual knowledge, seasons and nature. Within India itself, Holi is celebrated in different ways in different states: the Rang Panchmi in Uttar Pradesh, the Lath-Maar Holi in Barsana and Vrindavan, Ukkuli in the Konkan region, Manjal Kuli in Kerala, Shimga in Maharashtra, Shigmo in Goa, Dola in Odisha, Dol Jatra or Dol Purnima in West Bengal, Kumaoni Holi in Uttarakhand and many other different forms throughout India.