Dramatizing Dido, Circe, and Griselda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On Behalf of the Members and the Board of Directors of the Southern California Genealogical Society, Welcome to Today's Sessio

On behalf of the members and the Board of Directors of the Southern California Genealogical Society, welcome to today’s session! We hope that you enjoy it and that you’ll learn a new aspect of family history research from our speaker. Please spread the word about the Jamboree Extension Series. Tell your cousins and fellow genealogists. Upcoming presentations are listed at http://www.scgsgenealogy.com/JamboreeExtensionSeries2011.htm. Announcements of new sessions will be made through the SCGS blog at www.scgsgenealogy.blogspot.com. You can register to receive updates by email. Remember all these sessions are free and the original webcast is open to the public. All of the Jamboree Extension Series sessions will be archived and available for viewing 24/7 on the members-only portion of the SCGS website. This is only one of many benefits available for members of SCGS. You can join online at http://www.scgsgenealogy.com/catalog/index.php?cPath=30. Can you imagine what it would be among 1800 fellow genealogists and family historians, all of whom are enjoying informative sessions by knowledgeable and professional speakers? That’s the description of the Southern California Genealogy Jamboree, which will be held June 10-12, 2011, in Burbank. Keep updated on all things Jamboree by subscribing to email updates from the conference blog at www.genealogyjamboree.blogspot.com. If you have suggestions for improvement or ideas for future sessions, please contact us at [email protected]. Southern California Genealogical Society & Family Research Library Southern California Genealogy Jamboree 417 Irving Drive Burbank, CA 91504-2408 Office – 818.843.7247 • Fax – 818.688.3253 • [email protected] www.scgsgenealogy.com www.scgsgenealogy.blogspot.com www.genealogyjamboree.blogspot.com Tracing Your Immigrant Ancestors Presented by Lisa A. -

Jeudi 8 Juin 2017 Hôtel Ambassador

ALDE Hôtel Ambassador jeudi 8 juin 2017 Expert Thierry Bodin Syndicat Français des Experts Professionnels en Œuvres d’Art Les Autographes 45, rue de l’Abbé Grégoire 75006 Paris Tél. 01 45 48 25 31 - Facs 01 45 48 92 67 [email protected] Arts et Littérature nos 1 à 261 Histoire et Sciences nos 262 à 423 Exposition privée chez l’expert Uniquement sur rendez-vous préalable Exposition publique à l’ Hôtel Ambassador le jeudi 8 juin de 10 heures à midi Conditions générales de vente consultables sur www.alde.fr Frais de vente : 22 %T.T.C. Abréviations : L.A.S. ou P.A.S. : lettre ou pièce autographe signée L.S. ou P.S. : lettre ou pièce signée (texte d’une autre main ou dactylographié) L.A. ou P.A. : lettre ou pièce autographe non signée En 1re de couverture no 96 : [André DUNOYER DE SEGONZAC]. Ensemble d’environ 50 documents imprimés ou dactylographiés. En 4e de couverture no 193 : Georges PEREC. 35 L.A.S. (dont 6 avec dessins) et 24 L.S. 1959-1968, à son ami Roger Kleman. ALDE Maison de ventes spécialisée Livres-Autographes-Monnaies Lettres & Manuscrits autographes Vente aux enchères publiques Jeudi 8 juin 2017 à 14 h 00 Hôtel Ambassador Salon Mogador 16, boulevard Haussmann 75009 Paris Tél. : 01 44 83 40 40 Commissaire-priseur Jérôme Delcamp EALDE Maison de ventes aux enchères 1, rue de Fleurus 75006 Paris Tél. 01 45 49 09 24 - Facs. 01 45 49 09 30 - www.alde.fr Agrément n°-2006-583 1 1 3 3 Arts et Littérature 1. -

The Search for Lady Rose. Jeff Lewy Discusses the Mystery of His Titled Relative, Lady Rose, and How His Research Found the Answer

The Journal of the San Francisco Bay Area Jewish Genealogical Society Volume XXVIII, Number 2 May 2008 The Search for Lady Rose. Jeff Lewy discusses the mystery of his titled relative, Lady Rose, and how his research found the answer. See page 5. Also Inside this Issue SFBAJGS Counts Prominent Experts Among its Members....................................................3 All That Jazz, Genealogy Style.....................11 Departments Wedding of Basil Henriques and Rose Loewe, England, 1916. See page 7. Calendar.....................................................4, 12 President’s Message....................................... 2 Society News....................................................3 Family Finder Update.....................................10 Contributors to this Issue Jerry Delson, Beth Galleto, Jeremy Frankel, Excitement is building for the annual conference in Jeff Lewy. Chicago. See page 11. ZichronNote Journal of the San Francisco Bay Area Jewish Genealogical Society President’s Message ZichronNote Thoughts on Journal of the San Francisco Bay Area Jewish Genealogical Society Passover and Genealogy By Jeremy Frankel, SFBAJGS President © 2008 San Francisco Bay Area Jewish Genealogical Society I am writing this message at the time of year we celebrate Passover, when we recall the time our ZichronNote is published four times per year, in February, ancestors left the land of Mitzraim and spent 40 May, August and November. The deadline for contributions years wandering around the desert before entering is the first of the month preceding publication. The editor reserves the right to edit all submittals. Submissions may the Promised Land. Some people might view our be made by hard copy or electronically. Please email to passion for genealogy the same way; we take leave [email protected]. of our senses, spend many years lost in thought, and eventually (hopefully) we reach a satisfactory Reprinting of material in ZichronNote is hereby granted conclusion. -

Herminie a Performer's Guide to Hector Berlioz's Prix De Rome Cantata Rosella Lucille Ewing Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2009 Herminie a performer's guide to Hector Berlioz's Prix de Rome cantata Rosella Lucille Ewing Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Ewing, Rosella Lucille, "Herminie a performer's guide to Hector Berlioz's Prix de Rome cantata" (2009). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2043. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2043 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. HERMINIE A PERFORMER’S GUIDE TO HECTOR BERLIOZ’S PRIX DE ROME CANTATA A Written Document Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music and Dramatic Arts by Rosella Ewing B.A. The University of the South, 1997 M.M. Westminster Choir College of Rider University, 1999 December 2009 DEDICATION I wish to dedicate this document and my Lecture-Recital to my parents, Ward and Jenny. Without their unfailing love, support, and nagging, this degree and my career would never have been possible. I also wish to dedicate this document to my beloved teacher, Patricia O’Neill. You are my mentor, my guide, my Yoda; you are the voice in my head helping me be a better teacher and singer. -

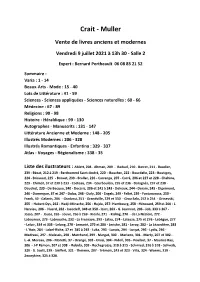

Crait - Muller

Crait - Muller Vente de livres anciens et modernes Vendredi 9 juillet 2021 à 13h 30 - Salle 2 Expert : Bernard Portheault 06 08 83 21 52 Sommaire : Varia : 1 - 14 Beaux-Arts - Mode : 15 - 40 Lots de Littérature : 41 - 59 Sciences - Sciences appliquées - Sciences naturelles : 60 - 66 Médecine : 67 - 89 Religions : 90 - 98 Histoire - Héraldique : 99 - 130 Autographes - Manuscrits : 131 - 147 Littérature Ancienne et Moderne : 148 - 205 Illustrés Modernes : 206 - 328 Illustrés Romantiques - Enfantina : 329 - 337 Atlas - Voyages - Régionalisme : 338 - 35 Liste des ilustrateurs : Ablett, 208 - Altman, 209 - Baduel, 210 - Barret, 211 - Baudier, 239 - Bécat, 212 à 219 - Berthommé Saint-André, 220 - Boucher, 222 - Bourdelle, 223 - Boutigny, 224 - Brissaud, 225 - Brouet, 239 - Bruller, 226 - Carrange, 207 - Carré, 206 et 227 et 228 - Chahine, 229 - Chimot, 37 et 230 à 233 - Cocteau, 234 - Courbouleix, 235 et 236 - Daragnès, 237 et 238 - Dauchot, 239 - De Becque, 240 - Decaris, 206 et 241 à 243 - Delvaux, 244 - Derain, 245 - Dignimont, 246 - Domergue, 37 et 247 - Dulac, 248 - Dufy, 206 - Engels, 249 - Falké, 239 - Fontanarosa, 250 - Frank, 40 - Galanis, 206 - Gradassi, 251 - Grandville, 329 et 330 - Grau Sala, 252 à 254 - Grinevski, 255 - Habert-Dys, 262 - Hadji-Minache, 256 - Hajdu, 257- Hambourg, 258 - Hérouard, 259 et 260 - L. Hervieu, 206 - Huard, 262 - Iacocleff, 348 et 350 - Icart, 263 - G. Jeanniot, 206 - Job, 333 à 367 - Josso, 207 - Jouas, 265 - Jouve, 266 à 269 - Kioshi, 271 - Kisling, 270 - de La Nézière, 272 - Laboureur, 273 - Labrouche, 232 - La Fresnaye, 293 - Lalau, 274 - Lalauze, 275 et 276 - Lebègue, 277 - Leloir, 334 et 335 - Lelong, 278 - Lemarié, 279 et 280 - Leriche, 281 - Leroy, 282 - La Lézardière, 283 - L’Hoir, 284 - Lobel-Riche, 37 et 285 à 292 - Luka, 293 - Lunois, 294 - Lurçat, 295 - Lydis, 296 - Madrassi, 297 - Malassis, 298 - Marchand, 299 - Margat, 300 - Mariano, 301 - Marty, 207 et 302 - L.-A. -

Instructions to Conform Legal Name of an Adult

INSTRUCTIONS TO CONFORM LEGAL NAME OF AN ADULT A person desiring to file an Application to Conform Legal Name of an Adult must have been a bona fide resident of Hamilton County for at least 60 days immediately prior to the filing of said application. You must present a certified copy of the adult’s birth certificate at the time of the Application as well as proof and support documentation showing the name that the applicant has been using. The support documentation must include an Official Identity Document (e.g., Driver’s License, passport, social security card, Medicaid/Medicare Card, Military ID, certified copy of Marriage License, etc.). The conformed name must be one of the names used on at least one Official Identity Document. Fill in all blanks except Case No. and hearing dates. A fee is required at the time of filing. Current Court Costs are posted at: https://www.probatect.org/about/general-resources. This fee must be paid in cash, money order, certified check (made payable to PROBATE COURT), MasterCard, Discover, American Express, or Visa. No personal checks will be accepted. The forms may be obtained from the Information Desk on the 9th floor of the Probate Court, 230 East 9th Street, Cincinnati, Ohio or by downloading the forms from our Web site, http://www.probatect.org. STEP 1: COMPLETE THE FOLLOWING FORMS Application to Conform Legal Name of Adult (Form 121.00) - Be sure to state your full legal name (first, middle and last) and full name requested after the name is conformed (first, middle and last). -

Travestis and Caractères in the Early Modern French Theatre

Early Theatre 15.1 (2012) Virginia Scott Conniving Women and Superannuated Coquettes: Travestis and Caractères in the Early Modern French Theatre In his 1651 Roman comique that depicts the adventures of an itinerant theat- rical troupe in the French provinces, Paul Scarron describes a conventional representation of older female characters in French comedy: ‘Au temps qu’on était réduit aux pièces de Hardy, il [La Rancune] jouait en fausset et, sous les masques, les roles de nourrice’ [In the period when troupes were reduced to the plays of Hardy, he played in falsetto, wearing a mask, the roles of the nurse].1 The nourrice was a character type from Roman and Italian Renais- sance comedy, often an entremetteuse or go-between as well as a confidant. Juliet’s Nurse in Romeo and Juliet, although she participates in a story that ends tragically, is an essentially comic character and a familiar example from the English repertory. La Rancune, an actor of the second rank, also played confidents, ambas- sadors, kidnappers, and assassins. This mixed emploi — confidents et nour- rices — was not an unusual line of business for an actor in the early years of the seventeenth century. A comparable emploi at the end of that century would be known as confidentes et caractères. The difference is that the former was an emploi for men while the latter was for women. Female character roles became more and more important in the last decades of the seventeenth century, when comedy dominated the Paris repertory and the bourgeoisie dominated the Paris theatre audience. When the professional theatre was established in Paris in the 1630s, no women specialized in comic charac- ter roles; by the end of that century, the troupe of the Comédie-Française included Mlles Desbrosses, Godefroy, Champvallon, and Du Rieu in the emploi of caractères. -

FOI/EIR FOI Section/Regulation S.8 Issue Pseudonyms Line to Take

FOI/EIR FOI Section/Regulation s.8 Issue Pseudonyms Line to take: Section 8 states that a request for information should state the name of the applicant. This means the applicant’s real name. Therefore a request made by an applicant using a pseudonym is not valid and the public authori ty would not be obliged to deal with the request. Similarly the Commissioner is not obliged to deal with a complaint made using a pseudonym as technically he has no legal authority to consider such complaints. However, it is the Commissioner’s position th at it would be contrary to the spirit of the Act to routinely or randomly check a complainant’s identity. Therefore the Commissioner will only decline to issue decision notices where the name used by the applicant is an obvious pseudonym or it comes to lig ht during the course of an investigation that the request was made using a pseudonym. Where the applicant has used what seems to be an obvious pseudonym, the onus is on the applicant to prove that they are in fact known by that name and thus that they have made a valid request. Where the requestor has used a name other than an obvious pseudonym, the Commissioner will assume that the applicant has provided his/her real name and expects public authorities to do likewise. If however a public authority suspect s the name given is false and refuses to deal with the request on that basis, it will then be up to the public authority to provide evidence to show that they have good reason to believe that the name used is a pseudonym and thus is an invalid request. -

Télécharger Un Extrait

TABLE DES MATIÈRES Avant-propos ..........................................................................................................................................................7 Introduction – Questionnements et contextes ................................................................................13 1. Prologues – Le Roi a la préséance ..................................................................................................49 2. Cadmus et Hermione – L’invention de la tragédie en musique ..........................................71 3. Alceste – La genèse d’un style..............................................................................................................95 4. Thésée – Omnia vincunt amor… gloriaque ......................................................................................123 5. Atys – L’accord tragique de la lyre..................................................................................................155 6. Isis – Au delà de la tragédie ..............................................................................................................179 7. Proserpine – Une prudence féministe dans un monde patriarcal ..................................207 8. Persée – Des rivalités de toutes parts ............................................................................................229 9. Phaéton – L’orgueil précède la chute ............................................................................................249 10. Amadis – Nouvelles directions et thèmes familiers..............................................................267 -

Data Standards Document

GEORGE MASON UNIVERSITY DATA STANDARDS DOCUMENT GGeeoorrggee MMaassoonn UUnniivveerrssiittyy PPaattrriioott PPrroojjeecctt DDaattaa SSttaannddaarrddss DDooccuummeenntt Last Updated: August 19, 2013 1 GEORGE MASON UNIVERSITY DATA STANDARDS DOCUMENT Table of Contents Chapter 1: Policies and Definitions ................................................................................... 4 Data Standards Development and Maintenance ........................................................................ 4 Current Committee Mission .................................................................................................... 4 Current Committee/Consultant Representation ...................................................................... 4 Committee Assignment .......................................................................................................... 5 Rules and Procedures ............................................................................................................ 5 Person Role Definitions and Assignments .................................................................................. 5 General Person Initial Entry and/or Update Responsibilities Role ................................................. 7 Chapter 2: Data Standards ................................................................................................... 8 Identification Number Standards ................................................................................................. 8 Name Standards ........................................................................................................................ -

Change of Name of an Adult

INSTRUCTIONS FOR CHANGE OF NAME OF AN ADULT A person desiring to file an Application for Change of Name of an Adult must have been a bona fide resident of Hamilton County for at least 60 days immediately prior to the filing of said application. Fill in all blanks except Case No. and hearing dates. A fee is required at the time of filing. Current Court Costs are posted at: https://www.probatect.org/about/general-resources. This fee must be paid in cash, money order, certified check (made payable to PROBATE COURT), MasterCard, Discover, American Express, or Visa. No personal checks will be accepted. IMPORTANT INFORMATION ABOUT PUBLICATION: Beginning August 17, 2021, Ohio Law no longer requires that applications to Change Name be set for formal hearing. However, a hearing may still be required in the Court’s discretion. If a hearing is requested by the Court, the application will be set for hearing at a future date and publication of notice may be required in a newspaper of general circulation in the County at least thirty (30) days before the hearing on the application. Otherwise, the application will be considered by the Magistrate who reviews the documents. If publication is required, you will use the NOTICE OF HEARING ON CHANGE OF NAME for this purpose. If you use the Cincinnati Court Index Press the NOTICE OF HEARING ON CHANGE OF NAME will be left with the cashier and the Cincinnati Court Index Press will pick up the notice. The Cincinnati Court Index Press will be paid directly by the Court from the initial filing fees for this case. -

Marketing “Proper” Names: Female Authors, Sensation

MARKETING “PROPER” NAMES: FEMALE AUTHORS, SENSATION DISCOURSE, AND THE MID-VICTORIAN LITERARY PROFESSION By Heather Freeman Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in English August, 2013 Nashville, Tennessee Approved: Carolyn Dever Jay Clayton Rachel Teukolsky James Epstein Copyright © 2013 by Heather Freeman All Rights Reserved For Sean, with gratitude for your love and unrelenting support iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation would not have been possible without the influence, patience, and feedback of a number of people, but I owe a particular debt to my committee, Professors Carolyn Dever, Jay Clayton, Rachel Teukolsky, and Jim Epstein. Their insightful questions and comments not only strengthened this project but also influenced my development as a writer and a critic over the last five years. As scholars and teachers, they taught me how to be engaged and passionate in the archive and in the classroom as well. My debt to Carolyn Dever, who graciously acted as my Director, is, if anything, compound. I cannot fully express my gratitude for her warmth, patience, incisive criticism, and unceasing willingness to read drafts, even when she didn’t really have the time. The administrative women of the English Department provided extraordinary but crucial support and encouragement throughout my career at Vanderbilt. Particular thanks go to Janis May and Sara Corbitt, and to Donna Caplan, who has provided a friendly advice, a listening ear, and much-needed perspective since the beginning. I also owe a great deal of thanks to my colleagues in the graduate program at Vanderbilt.