Women's Colleges and the Worlds We've Made of Them

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seven Sisters

SEVEN SISTERS 2012 SQUASH CHAMPIONSHIP From the Director of Athletics and Physical Education Welcome to the 2012 Seven Sisters Squash Championship!! Vassar College and the Department of Athletics & Physical Education, are very honored to be hosting the 2012 Seven Sisters Squash Championship! It is a particular distinction to be hosting this prestigious event on the eve of celebrating the 40th Anniversary of the enactment of Title IX. Recognizing the values of competition and sport has long been an integral part of the Seven Sisters relationship and honors the athletic capabilities and attributes of women. Enjoy your time at Vassar! We hope you have a chance to walk our beautiful campus, visit our local restaurants such as Baccio’s, Baby Cakes and the Beech Tree. Have a safe trip back home. Best Wishes, Sharon R. Beverly, Ph.D. Director of Athletics & Physical Education 2012 SEVEN SISTERS SQUASH CHAMPIONSHIPS SEVEN SISTERS CHAMPIONSHIP SCHEDULE --FEBRUARY 4, 2012 - KENYON HALL-- 10:30 AM VASSAR COLLEGE [24] VS. SMITH COLLEGE [25] 12:00 PM WELLESLEY COLLEGE [26] VS. MOUNT HOLYOKE COLLEGE [13] 1:30 PM COURTS 1,3,5 VASSAR COLLEGE [24] VS. WELLESLEY COLLEGE [26] COURTS 2,4,6 SMITH COLLEGE [25] VS. MOUNT HOLYOKE COLLEGE [13] 4:00 PM COURTS 1,3,5 VASSAR COLLEGE [24] VS. MOUNT HOLYOKE COLLEGE [13] COURTS 2,4,6 SMITH COLLEGE [25] VS. WELLESLEY COLLEGE [26] [College Squash Association Rankings as of 1/22/12] Scan for results and tournament page. VASSAR COLLEGE BREWers QUICK FACTS LOCATION: Poughkeepsie, NY FOUNDED: 1861 ENROLLMENT: 2,400 NICKNAME: Brewers COLORS: Burgundy and Gray AFFILIATION: NCAA Division III CONFERENCE: Liberty League PRESIDENT: Catharine Bond Hill DIRECTOR OF ATHLETICS & PHYSICAL EDUCATION: Dr. -

As Sex Discrimination in College Admissions

\\jciprod01\productn\H\HLC\51-2\HLC206.txt unknown Seq: 1 20-SEP-16 14:23 “Gender Balancing” as Sex Discrimination in College Admissions Shayna Medley* As women continue to apply to college in greater numbers than men and, on average, put forth stronger applications, many colleges have been engaging in “gender balancing” to ensure relatively even representation of the sexes on their campuses. This Note aims to call attention to the practice of gender bal- ancing and situate it in the context of the historic exclusion of women from higher education. Preference for male applicants is an open secret in the admis- sions world, but it remains relatively unknown to the majority of students and scholars alike. Those who have addressed the issue have often framed it as “affirmative action for men.” This Note takes issue with this characterization and proposes reconceptualizing “gender balancing” for what it really is — sex discrimination and an unspoken cap on female enrollment. Further, this Note argues that the “affirmative action for men” framework is detrimental both to the conception of race-based affirmative action and to sex discrimination. Af- firmative action attempts to counterbalance systemic educational inequalities and biased metrics that favor white, upper- and middle-class men. “Gender balancing,” on the other hand, finds no basis in either of the two rationales traditionally recognized by the Supreme Court as legitimate interests for affirm- ative action programs: remedying identified discrimination and promoting edu- cational diversity. Gender balancing cannot be legitimately grounded in either of these justifications, and thus should not be characterized as affirmative action at all. -

2019 20 Catalog

20 ◆ 2019 Catalog S MITH C OLLEGE 2 019–20 C ATALOG Smith College Northampton, Massachusetts 01063 S MITH C OLLEGE C ATALOG 2 0 1 9 -2 0 Smith College Northampton, Massachusetts 01063 413-584-2700 2 Contents Inquiries and Visits 4 Advanced Placement 36 How to Get to Smith 4 International Baccalaureate 36 Academic Calendar 5 Interview 37 The Mission of Smith College 6 Deferred Entrance 37 History of Smith College 6 Deferred Entrance for Medical Reasons 37 Accreditation 8 Transfer Admission 37 The William Allan Neilson Chair of Research 9 International Students 37 The Ruth and Clarence Kennedy Professorship in Renaissance Studies 10 Visiting Year Programs 37 The Academic Program 11 Readmission 37 Smith: A Liberal Arts College 11 Ada Comstock Scholars Program 37 The Curriculum 11 Academic Rules and Procedures 38 The Major 12 Requirements for the Degree 38 Departmental Honors 12 Academic Credit 40 The Minor 12 Academic Standing 41 Concentrations 12 Privacy and the Age of Majority 42 Student-Designed Interdepartmental Majors and Minors 13 Leaves, Withdrawal and Readmission 42 Five College Certificate Programs 13 Graduate and Special Programs 44 Advising 13 Admission 44 Academic Honor System 14 Residence Requirements 44 Special Programs 14 Leaves of Absence 44 Accelerated Course Program 14 Degree Programs 44 The Ada Comstock Scholars Program 14 Nondegree Studies 46 Community Auditing: Nonmatriculated Students 14 Housing and Health Services 46 Five College Interchange 14 Finances 47 Smith Scholars Program 14 Financial Assistance 47 Study Abroad Programs 14 Changes in Course Registration 47 Smith Programs Abroad 15 Policy Regarding Completion of Required Course Work 47 Smith Consortial and Approved Study Abroad 16 Directory 48 Off-Campus Study Programs in the U.S. -

NEWSLETTER Spring 2010 Volume LX, No

kosciuszko foundation T H E A M E R I C A N C EN T ER OF POLISH C UL T URE NEWSLETTER Spring 2010 Volume LX, No. 1 April 24, 2010 ISSN 1081-2776 at the Inside... Waldorf -Astoria Message from the 2 President and Executive Director Message from the 3 Chairman National Polish Center 4 Joins Forces with the KF “Spirit of Polonia” 5 Sculpture Exhibition Professor Smialowski 6 Award KF 75th Anniversary 6 Dinner and Ball 7 New Exchange Program Tribute to Warsaw 8 Uprising Teaching English in 9 Poland Exchange Fellowships 10 and Grants Scholarships and 13 Grants for Americans The Year Abroad Program 16 in Poland Graduate Studies and 16 Research in Poland 17 Summer Sessions Awards Kosciuszko Foundation 18 Chapters Children’s Programs 21 at the KF 22 Contributors 23 Giving to the Kosciuszko Foundation For full details 24 Calendar of Events turn to page 6 Message from the President and Executive Director Alex Storozynski As the President of the Kosciuszko Foundation, I often get was undeniably anti-PRL. Additionally, in June 1986, during unusual requests for money from people who think that a customs control while crossing the border, it was revealed that the Foundation is sitting on piles of cash, just waiting to be he tried to smuggle illegal newsletters out of the country. Having handed out on a whim. That’s not the case. considered all of the activities of A.S. during his stay in the PRL while on scholarship, he was entered into the registry of The scholarship endowment governed by the Foundation’s individuals considered undesirable in the PRL. -

The Right to Education in the United States: Beyond the Limits of the Lore and Lure of Law Roger J.R

Annual Survey of International & Comparative Law Volume 4 | Issue 1 Article 10 1997 The Right to Education in the United States: Beyond the Limits of the Lore and Lure of Law Roger J.R. Levesque Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.ggu.edu/annlsurvey Part of the Other Law Commons Recommended Citation Levesque, Roger J.R. (1997) "The Right to Education in the United States: Beyond the Limits of the Lore and Lure of Law," Annual Survey of International & Comparative Law: Vol. 4: Iss. 1, Article 10. Available at: http://digitalcommons.law.ggu.edu/annlsurvey/vol4/iss1/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Academic Journals at GGU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Annual Survey of International & Comparative Law by an authorized administrator of GGU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Levesque: The Right to Education THE RIGHT TO EDUCATION IN THE UNITED STATES: BEYOND THE LIMITS OF THE LORE AND LURE OF LAW ROGER J.R. LEVESQUE· The author argues that U.S. as well as international law on educational rights needs to incorporate an important, but heretofore neglected, dimension. U.S. legislation and court decisions, as well as existing international instruments on educational rights focus chiefly on educational access and assign responsibility and authority over educational content and methods almost exclusively to the state and parents. The ideas, concerns and wishes of the young people being educated remain largely unacknowledged and disregarded. The author maintains that only to the extent our understanding of educational rights is rethought to include "youth's self determination of education for citizenship" can we expect to improve academic performance, overcome negative attitudes toward school, and adequately prepare children and youth for life in a democratic, pluralistic society and an increasingly interdependent world. -

Constructing Womanhood: the Influence of Conduct Books On

CONSTRUCTING WOMANHOOD: THE INFLUENCE OF CONDUCT BOOKS ON GENDER PERFORMANCE AND IDEOLOGY OF WOMANHOOD IN AMERICAN WOMEN’S NOVELS, 1865-1914 A dissertation submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Colleen Thorndike May 2015 Copyright All rights reserved Dissertation written by Colleen Thorndike B.A., Francis Marion University, 2002 M.A., University of North Carolina at Charlotte, 2004 Ph.D., Kent State University, 2015 Approved by Robert Trogdon, Professor and Chair, Department of English, Doctoral Co-Advisor Wesley Raabe, Associate Professor, Department of English, Doctoral Co-Advisor Babacar M’Baye, Associate Professor, Department of English Stephane Booth, Associate Provost Emeritus, Department of History Kathryn A. Kerns, Professor, Department of Psychology Accepted by Robert Trogdon, Professor and Chair, Department of English James L. Blank, Interim Dean, College of Arts and Sciences TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments .......................................................................................................................... iv Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1: Conduct Books ............................................................................................................ 11 Chapter 2 : Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women and Advice for Girls .......................................... 41 Chapter 3: Bands of Women: -

The Need for Early Childhood Remedies in School Finance Litigation, 70 Ark

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Law Faculty Publications School of Law 2017 Why Kindergarten is Too Late: The eedN for Early Childhood Remedies in School Finance Litigation Kevin Woodson University of Richmond, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.richmond.edu/law-faculty-publications Part of the Education Law Commons Recommended Citation Kevin Woodson, Why Kindergarten is Too Late: The Need for Early Childhood Remedies in School Finance Litigation, 70 Ark. L. Rev. 87 (2017). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Why Kindergarten Is Too Late: The Need for Early Childhood Remedies in School Finance Litigation Kevin Woodson- I. INTRODUCTION In 2006, Jim Ryan, then a law professor, now dean of Harvard University's School of Education, published A ConstitutionalRight to Preschool,' a seminal article that argued that courts should require states to fund public preschools as a means of abiding by their constitutional obligations to provide all children adequate educational opportunities.2 Though very few courts have ever imposed such a requirement,3 and all but one of these rulings have been eliminated on appeal,' Ryan noted the political popularity of universal preschool and a growing trend among states to provide free pre-kindergarten as grounds for optimism that courts might be more open to ordering preschool remedies in future litigation.' . Associate Professor, Drexel University, Thomas R. -

HCS — History of Classical Scholarship

ISSN: 2632-4091 History of Classical Scholarship www.hcsjournal.org ISSUE 1 (2019) Dedication page for the Historiae by Herodotus, printed at Venice, 1494 The publication of this journal has been co-funded by the Department of Humanities of Ca’ Foscari University of Venice and the School of History, Classics and Archaeology of Newcastle University Editors Lorenzo CALVELLI Federico SANTANGELO (Venezia) (Newcastle) Editorial Board Luciano CANFORA Marc MAYER (Bari) (Barcelona) Jo-Marie CLAASSEN Laura MECELLA (Stellenbosch) (Milano) Massimiliano DI FAZIO Leandro POLVERINI (Pavia) (Roma) Patricia FORTINI BROWN Stefan REBENICH (Princeton) (Bern) Helena GIMENO PASCUAL Ronald RIDLEY (Alcalá de Henares) (Melbourne) Anthony GRAFTON Michael SQUIRE (Princeton) (London) Judith P. HALLETT William STENHOUSE (College Park, Maryland) (New York) Katherine HARLOE Christopher STRAY (Reading) (Swansea) Jill KRAYE Daniela SUMMA (London) (Berlin) Arnaldo MARCONE Ginette VAGENHEIM (Roma) (Rouen) Copy-editing & Design Thilo RISING (Newcastle) History of Classical Scholarship Issue () TABLE OF CONTENTS LORENZO CALVELLI, FEDERICO SANTANGELO A New Journal: Contents, Methods, Perspectives i–iv GERARD GONZÁLEZ GERMAIN Conrad Peutinger, Reader of Inscriptions: A Note on the Rediscovery of His Copy of the Epigrammata Antiquae Urbis (Rome, ) – GINETTE VAGENHEIM L’épitaphe comme exemplum virtutis dans les macrobies des Antichi eroi et huomini illustri de Pirro Ligorio ( c.–) – MASSIMILIANO DI FAZIO Gli Etruschi nella cultura popolare italiana del XIX secolo. Le indagini di Charles G. Leland – JUDITH P. HALLETT The Legacy of the Drunken Duchess: Grace Harriet Macurdy, Barbara McManus and Classics at Vassar College, – – LUCIANO CANFORA La lettera di Catilina: Norden, Marchesi, Syme – CHRISTOPHER STRAY The Glory and the Grandeur: John Clarke Stobart and the Defence of High Culture in a Democratic Age – ILSE HILBOLD Jules Marouzeau and L’Année philologique: The Genesis of a Reform in Classical Bibliography – BEN CARTLIDGE E.R. -

March 09 Newsletter

Reference NOTES A Program of the Minnesota Office of Higher Education and the University of Minnesota-Twin Cities March 2009 Minitex (not MINITEX) and MnKnows Bill DeJohn, Minitex Director Inside This Issue Over the next few months, you will be watching our migration to a new name, Minitex (upper and lower case on Minitex), and a new name for a new portal Minitex (not MINITEX) and MnKnows 1 site, MnKnows, (or, read it, Minnesota Knows, if you prefer). MnKnows will provide single-site access to Ada Comstock – Educator the MnLINK Gateway, ELM, Minnesota Reflections, and Transformer 1 AskMN, and the Research Project Calculator – the Minitex services used most by the general public. For more information about these changes, see the article Library Technology Conference “And, What’s in a Name: MINITEX to Minitex and a new one, MnKnows” in Re-cap Information Commons 2 Minitex E-NEWS #93: http://minitex.umn.edu/publications/enews/2009/093.pdf The Keynote Speech of Eric Lease Morgan 2 Ada Comstock – Educator and Transformer Library 2.0 and Google Apps 3 Carla Pfahl E-Resource Management 4 March is Women’s History Month, and we thought it What Everything Has to Do would be a good idea to highlight a Minnesotan who with Everything 4 played a part in history by reshaping the higher education system for women. Ada Comstock was born in 1876 and Library Technology Programs for raised in Moorhead, MN. After excelling in the various Baby Boomers and Beyond 4 schools Ada attended, she graduated from high school The Opposite of Linear: early and began her undergraduate career at the age of 16 Learning at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis in 1892. -

Honolulu Advertiser & Star-Bulletin Obituaries

Honolulu Advertiser & Star-Bulletin Obituaries January 1 - December 31, 2001 L LEVI LOPAKA ESPERAS LAA, 27, of Wai'anae, died April 18, 2001. Born in Honolulu. A Mason. Survived by wife, Bernadette; daughter, Kassie; sons, Kanaan, L.J. and Braidon; parents, Corinne and Joe; brothers, Joshua and Caleb; sisters, Darla and Sarah. Memorial service 5 p.m. Monday at Ma'ili Beach Park, Tumble Land. Aloha attire. Arrangements by Ultimate Cremation Services of Hawai'i. [Adv 29/4/2001] Mabel Mersberg Laau, 92, of Kamuela, Hawaii, who was formerly employed with T. Doi & Sons, died Wednesday April 18, 2001 at home. She was born in Puako, Hawaii. She is survived by sons Jack and Edward Jr., daughters Annie Martinson and Naomi Kahili, sister Rachael Benjamin, eight grandchildren, 12 great-grandchildren and a great-great-grandchild. Services: 11 a.m. Tuesday at Dodo Mortuary. Call after 10 a.m. Burial: Homelani Memorial Park. Casual attire. [SB 20/4/2001] PATRICIA ALFREDA LABAYA, 60, of Wai‘anae, died Jan. 1, 2001. Born in Hilo, Hawai‘i. Survived by husband, Richard; daughters, Renee Wynn, Lucy Evans, Marietta Rillera, Vanessa Lewi, Beverly, and Nadine Viray; son, Richard Jr.; mother, Beatrice Alvarico; sisters, Randolyn Marino, Diane Whipple, Pauline Noyes, Paulette Alvarico, Laureen Leach, Iris Agan and Rusielyn Alvarico; brothers, Arnold, Francis and Fredrick Alvarico; 17 grandchildren; four great-grandchildren. Visitation 6 to 9 p.m. Wednesday at Nu‘uanu Mortuary, service 7 p.m. Visitation also 8:30 to 10:30 a.m. Thursday at the mortuary; burial to follow at Hawai‘i State Veterans Cemetery. -

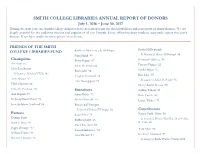

2017 Annual Report of Donors

SMITH COLLEGE LIBRARIES ANNUAL REPORT OF DONORS July 1, 2016 – June 30, 2017 During the past year, the Smith College Libraries have benefited from the thoughtfulness and generosity of many donors. We are deeply grateful for the enduring interest and support of all our Friends. Every effort has been made to accurately report this year’s donors. If we have made an error, please let us know. ______________________________________________________________________________________________________ FRIENDS OF THE SMITH Kevin McDonough COLLEGE LIBRARIES FUND Kathleen McCartney & Bill Hagen Nina Munk ’88 In Memory of Marcia McDonough ’54 Champions Betsy Pepper ’67 Elizabeth McEvoy ’96 Anonymous Sarah M. Pritchard Frances Pepper ’62 Mary-Lou Boone Ruth Solie ’64 Sandra Rippe ’67 In honor of Martha G.Tolles ’43 Virginia Thiebaud ’72 Rita Saltz ’60 Anne Brown ’62 Amy Youngquist ’74 In memory of Sarah M. Bolster ’50 Edith Dinneen ’40 Cheryl Stadel-Bevans ’90 Christine Erickson ’65 Sustainers Audrey Tanner ’91 Ann Kaplan ’67 Susan Baker ’79 Ruth Turner ’46 M. Jenny Kuntz Frost ’78 Sheila Cleworth ’55 Lynne Withey ’70 Joan Spillsbury Stockard ’53 Rosaleen D'Orsogna In honor of Rebecca D'Orsogna ’02 Contributors Patrons Susan Flint ’78 Nancy Veale Ahern ’58 Deanna Bates Barbara Judge ’46 In memory of Marian Mcmillan ’26 & Gladys Mary F. Beck ’56 B. Veale ’26 Paula Kaufman ’68 Peggy Danziger ’62 Susan Lindenauer ’61 Amy Allen ’90 Stefanie Frame ’98 Ann Mandel ’53 Kathleen Anderson ’57 Marianne Jasmine ’85 In memory of Bertha Watters Tildsley 1894 Elise Barack ’71 Kate Kelly ‘73 Sally Rand ‘47 In memory of Sylvia Goetzl ’71 Brandy King ’01 Katy Rawdon ’95 Linda Beech ’62 Claudia Kirkpatrick ’65 Eleanor Ray Sarah Bellrichard ’94 Jocelyne Kolb ’72 In memory of Eleanor B. -

Teaching About Women's Lives to Elementary School Children

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Women's Studies Quarterly Archives and Special Collections 1980 Teaching about Women's Lives to Elementary School Children Sandra Hughes How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/wsq/449 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Teaching about Women's Lives to Elementary School Children By Sandra Hughes As sixth-grade teachers with a desire to teach students about the particular surprised me, for they showed very little skepticism of historical role of women in the United States, my colleague and I a "What do we have to do this for?" nature. I found that there created a project for use in our classrooms which would was much opportunity for me to teach about the history of maximize exposure to women's history with a minimum of women in general, for each oral report would stimulate teacher effort. This approach was necessary because of the small discussion not only about the woman herself, but also about the amount of time we had available for gathering and organizing times in which she lived and the other factors that made her life material on the history of women and adapting it to the what it was. Each student seemed to take a particular pride in elementary level. the woman studied-it could be felt in the tone of their voices Since textbook material on women is practically when they began, "My woman is .