Economic Significance of Alaska Railroad

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alberta-To-Alaska-Railway-Pre-Feasibility-Study

Alberta to Alaska Railway Pre-Feasibility Study 2015 Table of Content Executive Summary ...................................................................................................... i Infrastructure and Operating Requirements................................................................ ii Environmental Considerations and Permitting Requirements .................................... ii Capital and Operating Cost Estimates ......................................................................... iii Business Case .............................................................................................................. iii Mineral Transportation Potential ................................................................................ iii First Nations/Tribes and Other Contacts ..................................................................... iv Conclusions .................................................................................................................. iv 1 | Introduction ........................................................................................................ 1 This Assignment............................................................................................................ 1 This Report ................................................................................................................... 2 2 | Infrastructure and Operating Requirements ........................................................ 3 Route Alignment .......................................................................................................... -

A Tale of Perseverance and Ingenuity Perseverance of a Tale by Ben Traylor

A Tale of Perseverance and Ingenuity Perseverance of A Tale by Ben Traylor Through excellent customer service and sound business management practices, provide safe, efficient, and economical transportation and real estate services that support and grow economic development opportunities for the State of Alaska. by Scott Adams Scott by TABLE OF CONTENTS Alaska Railroad Leadership 1 Leadership Year in Review 2 Business Highlights 8 Financial Highlights 10 Transmittal Letter 12 AUDITED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS SECTION Contact Information and Office Locations Back by Judy Patrick Judy by MANAGEMENT TEAM Clark Hopp Jim Kubitz Chief Operating Officer VP Real Estate Barbara Amy Brian Lindamood Chief Financial Officer VP Engineering Andy Behrend Dale Wade Chief Counsel VP Marketing and Bill O’Leary Customer Service President & CEO Jennifer Haldane Chief Human Resources Officer BOARD OF DIRECTORS Craig Campbell Judy Petry Julie Anderson John Binkley Chair Vice Chair Commissioner Director Gov. Mike Dunleavy appointed Bill Sheffield as by Ken Edmier Ken by Chair Emeritus Jack Burton John MacKinnon John Shively Director Commissioner Director 1 YEAR IN REVIEW A Tale of Perseverance and Ingenuity Once upon a time, in a world not yet steeped in pandemic, the Alaska Railroad Corporation (ARRC) began the year 2020 with optimism, ready to share a story of emergence from fiscal uncertainty. Yet, when the last page turned on 2020, our tale didn’t end with happily-ever-after; nor did it conclude as a tragedy. Instead, 2020’s narrative featured everyday heroes, brandishing their perseverance and ingenuity to fight common foes — the villain Pandemic and its sidekick Recession. Just two months into a promising new year, the rogue novel coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) appeared on scene, soon spreading throughout the land. -

WSK Commuter Rail Study

Oregon Department of Transportation – Rail Division Oregon Rail Study Appendix I Wilsonville to Salem Commuter Rail Assessment Prepared by: Parsons Brinckerhoff Team Parsons Brinckerhoff Simpson Consulting Sorin Garber Consulting Group Tangent Services Wilbur Smith and Associates April 2010 Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.......................................................................................................... 1 INTRODUCTION................................................................................................................... 3 WHAT IS COMMUTER RAIL? ................................................................................................... 3 GLOSSARY OF TERMS............................................................................................................ 3 STUDY AREA....................................................................................................................... 4 WES COMMUTER RAIL.......................................................................................................... 6 OTHER PASSENGER RAIL SERVICES IN THE CORRIDOR .................................................................. 6 OUTREACH WITH RAILROADS: PNWR AND BNSF .................................................................. 7 PORTLAND & WESTERN RAILROAD........................................................................................... 7 BNSF RAILWAY COMPANY ..................................................................................................... 7 ROUTE CHARACTERISTICS.................................................................................................. -

An Overview of U.S. Commuter Rail

AN OVERVIEW OF U.S. COMMUTER RAIL Timothy J. Brock, MA Reginald R. Souleyrette, PhD, PE KTC-13-18/UTCNURAIL1-12-1F This research was sponsored by: The NuRail Center National University Transportation Center and The Kentucky Transportation Center University of Kentucky Cover Photo: Tri-Rail System in Miami, Florida By: Timothy J. Brock Date: April, 2011 Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank Dr. Ted Grossardt and Dr. Len O’Connell for their comments on earlier drafts. They would also like to thank the participants in the Cities, Transportation and Sustainability session at the Association of American Geographers annual meeting for the thoughtful discussion and comments on this research. Disclaimer: The contents of this report reflect the views of the authors who are responsible for the facts and accuracy of the data presented herein. The contents do not necessarily reflect the official views or policies of the Kentucky Transportation Center or of the NuRail Center. This report does not constitute a standard, specification or regulation. ii AN OVERVIEW OF U.S. COMMUTER RAIL Timothy J. Brock, M.A. Research Associate Kentucky Transportation Center University of Kentucky and Reginald R. Souleyrette, Ph.D., P.E. Professor of Transportation Engineering and Commonwealth Chair College of Engineering University of Kentucky FINAL REPORT May 2nd, 2013 © 2013 University of Kentucky, Kentucky Transportation Center Information may not be used, reproduced, or republished without our written consent. iii 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient’s Catalog No KTC-13-18/UTCNURAIL1-12-1F 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date May 2013 AN OVERVIEW OF U.S. -

Annotated Bibliography of Alaska Railroad & Related Timber Bridges

ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY OF ALASKA RAILROAD & RELATED TIMBER BRIDGES November 2008 Prepared for: Alaska Railroad Corporation Anchorage, Alaska http://www.akrr.com Historical Consultant: Alaska Railroad Annotated Bibliography Page 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page I. General Historical Works: Timber and Trestle Bridges 2 II. General Engineering and Technical Works 5 III. Railroad Periodicals and Engineering Trade Journals: 9 Key (Historical Articles on Trestles IV. Railroad Periodicals and Engineering Trade Journals: 10 Articles on Alaska Railroad and Trestle Construction V. Illustrated Publications and Rail Enthusiast Periodicals 11 VI. Drawings, Maps and Photographs 12 VII. Unpublished Technical Reports and Surveys 13 VIII. Unpublished Historical Reports, National Register Surveys 14 and Historical Documentation IX. General Historical Works: Alaska Railroad 18 APPENDIX: Examples of Illustrations and Documentary 20 Materials from Sources Cited in Bibliography Alaska Railroad Annotated Bibliography Page 2 Annotated Bibliography of Alaska Railroad and Related Timber Bridges November 21, 2008 I. General Historical Works: Timber and Trestle Bridges Austill, H. “Use of Wood on American Railroads.” Transactions of the American Society of Civil Engineers. (New York: ASCE, 1953): pp. 797-804. As part of its 100th anniversary celebration, the American Society of Civil Engineers issued a special centennial edition of its Transactions, featuring papers on the major sub-fields of the profession. Within structural engineering, four papers were published encompassing various aspects of wooden bridges and trestles, and timber construction technology. Austill’s paper, on the use of wood in American railroad structures, provides a concise account of both railroad trestle and truss development, including the growing use of treated timber in these wooden structures. -

Haines Rail Access Report

HAINES RAIL ACCESS REPORT APRIL 2014 April 18, 2014 HAINES RAIL ACCESS REPORT Prepared for: The Borough of Haines and The State of Alaska Prepared By: ALCAN RaiLink Inc. Operating as PROLOG Canada Inc. HAINES RAIL ACCESS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report provides a business case assessment for rail access to tidewater at Haines, Alaska for Yukon mineral exports, and to bridge Alaska Railroad traffic from the south. Haines, Alaska is in a regionally unique position of having a well protected, deep water port with substantial back-up lands available to support high volume rail operations that may be required to fully develop Yukon resources. In turn Yukon mineral resources are the principal traffic source available for a Haines railway project. As summarized in the following chart, this report has updated the full resource development potential, as well as Alaska Railroad bridge traffic, that would support, and be supported by, Haines Rail Access over a 30 year investment life-cycle. Potential Haines Rail Access traffic peaks at over 6 million tons/year excluding Crest Iron Ore traffic, which is 28 million tons/year. Haines Rail Access Traffic Forecast 7,000,000 Min (Total Producing) 6,000,000 Near (Producing+Advancing) 5,000,000 Mid (Producing+Advancing 4,000,000 +Probable) 3,000,000 Max (Prod.+Adv.+Prob. Tons/Year +Possible+Alaska) 2,000,000 Max+Undiscovered 1,000,000 Alaska Rail Bridge Traffic 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 Total All Traffic Period (year) Haines Rail Access Report Page i HAINES RAIL ACCESS REPORT Four scenarios for Haines Rail Access are analyzed including potential synergies with a proposed Alberta Oil Sands Railway connecting to the Alaska Railroad Northern Extension Project at Delta Junction, Alaska. -

Alaska Roads Historic Overview

Alaska Roads Historic Overview Applied Historic Context of Alaska’s Roads Prepared for Alaska Department of Transportation and Public Facilities February 2014 THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK Alaska Roads Historic Overview Applied Historic Context of Alaska’s Roads Prepared for Alaska Department of Transportation and Public Facilities Prepared by www.meadhunt.com and February 2014 Cover image: Valdez-Fairbanks Wagon Road near Valdez. Source: Clifton-Sayan-Wheeler Collection; Anchorage Museum, B76.168.3 THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK Table of Contents Table of Contents Page Executive Summary .................................................................................................................................... 1 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 3 1.1 Project background ............................................................................................................. 3 1.2 Purpose and limitations of the study ................................................................................... 3 1.3 Research methodology ....................................................................................................... 5 1.4 Historic overview ................................................................................................................. 6 2. The National Stage ........................................................................................................................ -

The Bachelors' NRHS Convention Adventure, Pt. 2

BSRA Entertainment Report for October 3, 2015 LONG FORM (for historical record) Entertainment Report for October 3, 2015 October 3, 2015. The Bachelder's NRHS Convention Adventure Part 2. Leonard and Nancy Bachelder attended the 2013 NRHS convention in Alaska, making a 6-week trip through Canada and Alaska, of which we saw part 1 in March. Part 2 picked up as Len and Nancy rode in a 15 passenger van from the Yukon Territory into Alaska. The first photo was of the customs house at Poker Creek, Alaska, the most northerly land border port in the USA. Then we saw Chicken, Alaska, once somewhat populous as a Gold Rush town, but now of estimated population 10 to 20 (7 according to the US Census of 2010); it was supposed to be named Ptarmigan, but people could not agree on the spelling, so the US Post Office had good reason to believe that people in general would not be able to spell the proposed name, and refused to accept it; thus, the town wound up with its current name. Gold mining still takes place in the surrounding area, but the population of Chicken is occupied with operating the town as a tourist trap. Next stop was Fairbanks, with still over a week before the convention, so Len and Nancy went to the University of Alaska, where they found out about removal of Aleutian Islanders during World War II. We also saw a monument in downtown Fairbanks to American pilots who brought airplanes to Fairbanks for Russian pilots to pick up for use during World War II. -

WINTEK VIEW of MOUNT Mckinley from the NORTHWEST. UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT of the INTERIOR Harold L

GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 907 FRONTISPIECE WINTEK VIEW OF MOUNT McKINLEY FROM THE NORTHWEST. UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Harold L. Ickes, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY W. C. Mendenhall, Director Bulletin 907 GEOLOGY OF THE ALASKA RAILROAD REGION BY STEPHEN R. CAPPS UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1940 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents. Washington, D. C. ..... Price $1.25 (paper) ft 3 -vu> CONTENTS Page Abstract. _._._.-._.._.___._______-_---.--_--__------_--..-.-.-__._ 1 Introduction.._.._..._..__-__-__-------l---_._-...--.-.---_-__.-_. 1 History., of, exploration. _..__._.._._-----..--_.___-____.-_-____.-__.. 4 Present report__....--..-__._-.--------.----...----_----_----.-._ 21 Geography.. .-...._-.___-_--.-------_------_-__--.-_-----___.._ 23- Geographic provinces._______----_--_----_-_._---.---_.--...._. 23' Chugach-Kenai Mountains._----_---_.__--_--_---.---...-.. 24 Talkeetna Mountains._-_-------_---__--._.____._-..._-._.. 25 Cook Inlet-Susitna lowland.-----_----__--_---.-_---_-,-_-__ 26 Copper-Susitna lowland._------------..___-..._.--_.-.-.-._ 27 Alaska Range.______.___------__----_-_-__--_-_-__________ 27 Tanana-Kuskokwim lowland.._-..__.__._.__._._____.__.____ 29 Yukon-Tanana'upland. __--_------------__--------------.-- 30 Climate. _-_-__-------_---_-_-----------_-----------._-_-_-_--_ 31 Vegetation... _._._.__._-:___-.._.---.___.--._----__-_-__--._-__ 33 Animal life.___-_---_-_--_----_-----------_-------__.-__.---._ 35 Population..................----.-.----I.-.-..--.-.-......... -

2011 Community Ties Archive

Printed on Member & recycled Supporter paper Alaska Railroad Ongoing Projects: Alaska Railroad Corporation Northern Rail Extension 1st Quarter, 2011 and Tanana River Crossing www.AlaskaRailroad.com • (907) 265-2300 Fairbanks Intermodal “RAILROAD DAYS” OPEN HOUSES RETURN Improvements ARRC schedules popular springtime community events North Pole Road/Rail The Alaska Railroad Corporation (ARRC) invites the public to two Railroad Days open Crossing Reduction house events in late spring. The Anchorage event is 11:00 a.m. to 3:00 p.m. on Saturday, May 7, at the Anchorage Historic Depot. The Fairbanks event is 10:00 a.m. to 2:00 p.m. on Saturday, May 14, at the Fairbanks Depot. Positive Train Control The last ARRC community open houses were held in 2008 and were suspended in 2009 Port MacKenzie Rail Extension and 2010 due to capital project construction and cost-cutting measures. Railroad Days events provide Alaskans with a unique opportunity to learn about the state’s railroad. Healy Canyon Safety and TThe events will feature ever-popular free train rides and static displays of locomotives, railcars and Reliability Improvements other equipment that afford an up-close, hands-on experience. Events will also include live band entertainment and several activities geared toward children, such as railroad balloons and tattoos. Hot dogs and beverages will be available for purchase and the railroad’s depot gift shops and rail ticket Ship Creek Intermodal Center counters will also be open. These events have drawn several thousand people to participate in years past and there is every Chugach Forest Whistle Stop indication that attendance will be similar in 2011. -

State Historic Preservation Officer Certification the Evaluated Significance of This Property Within the State Is

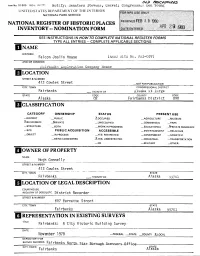

:ormNO. 10-300 REV. 0/77) Notifyj Senators Stevens, Gravel; Congressman Don Young UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS [NAME HISTORIC Falcon Joslin House ^o tflTi; NO. FAl-03?) AND/OR COMMON _______Fairbanks Exploration Company House LOCATION STREET & NUMBER 413 Cowles Street _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Fairbanks __ VICINITYOF Alaska at large STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Alaska 02 Fairbanks District 090 CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE .DISTRICT _PUBLIC —^.OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM LBUILDING(S) —XPRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK .STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL -^PRIVATE RESIDENCE -SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS -OBJECT _IN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED AYES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER: [OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Huah Connellv STREET & NUMBER 413 Cowles Street CITY. TOWN STATE Fairbanks _ VICINITYOF Alaska 99701 HLOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEED^ETC. District Recorder STREET & NUMBER 607 Barnette Street CITY, TOWN STATE Fairbanks Alaska 99701 H REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Fairbanks: A City Historic Building Survey DATE November 1978 —FEDERAL _STATE —COUNTY X.LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEYRECORDS Fairbanks North Star Borough Ac^nr. (if fir*.. CITY, TOWN _ . „ STATE Fairbanks Alaska DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED JtORIGINALSITE —GOOD —RUINS JLALTERED —MOVED DATE- X.FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Located within the original Fairbanks townsite, the Falcon Joslin house is a two-and-a-half story detached, "square-built" wood-frame structure with a single-story room built onto the east gable facade. -

The Historic Preservation Plan

Commission on Historic Preservation City of Fairbanks & the Fairbanks North Star Borough The Historic Preservation Plan A Guide To Preservation Management THE HISTORIC PRESERVATION PLAN Prepared by COMMISSION ON HISTORIC PRESERVATION CITY OF FAIRBANKS & THE FAIRBANKS NORTH STAR BOROUGH Jim Whitaker, Mayor, Fairbanks North Star Borough Steve M. Thompson, Mayor, City of Fairbanks Commission on Historic Preservation Claus-M. Naske Dr. LaJuana K. Williams Allan Renfroe James Johnson Jim Allan Robert Kilborn Patricia Sackinger Fairbanks North Star Borough Department of Community Planning Bernardo Hernandez, Director Jeff Bouton, Planner III Adopted July 13, 2006 Ordinance No. 2006-42 Revised February 22, 2007 Ordinance No. 2007-11 CONTENTS Executive Summary …………………………………………………………………………………… Page 1 Goals A Vision of Preservation Recommendations & Implementation Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………………………… Page 3 Why Historic Preservation? Why Preservation Planning? Trends Affecting Historic Resources Overview Purpose Public Involvement Historic Context ………………………………………………………………………………………… Page 6 Physical Setting & History. Prehistoric & Early Native Settlement Settlement Commerce & Economic Development Military & Government Transportation & Communication Social Institutions Recommendation for Further Surveys FNSB Historic Landmarks & National Register of Historic Places Bibliography Preservation Issues ………………………………………………………………………………….. Page 19 Preservation Opportunities ………………………………………………………………………… Page 20 Vision, Goals & Objectives ………………………………………………………………………….