The Ingenious Pen: American Writing Implements from the Eighteenth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boxes, Inkwells, Speech and Formulas DRAFT

Boxes, Inkwells, Speech and Formulas DRAFT Richard J. Fateman March 10, 2006 1 Introduction This paper sets out some designs for entering mathematical formulas into a computer system. An initial approach to this task suggests that the previous model, namely writing mathematics on paper or chalkboard, should lead to a natural computer system using a stylus for writing on a tablet. For feedback and for presentation such as in this paper, we use the typesetting capabilities of Knuth’s TEX system to show how “properly typeset” expressions might appear. We use TEX here to show our design for an interactive input scheme, under implementation. For this to work, an interactive system must make expressions appear approximately in the same sequences as illustrated, on a computer display. The solid color boxes that appear in the incomplete forms are intended as invitations for the user to continue writing out a formula, continuing from within one of those boxes. Think of them as “virtual inkwells.” For example, an attempt to write a superscript must begin by dipping the stylus (or mouse) in the superscript inkwell. An attempt to write an operand adjacent to an existing must begin in that inkwell. Initiating writing elsewhere on the screen will have no proper ink and will not contribute to the formula entry. We also point out that speaking the terms, rather than writing them, may provide more accurate communication. At this point we suggest you look ahead a page or two to see some pictures of inkwells. 1.1 Why Inkwells? This ink-well-based constrained input provides an obvious basis for cooperation between the human entering a formula and the supporting computer program. -

A Study of Kufic Script in Islamic Calligraphy and Its Relevance To

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 1999 A study of Kufic script in Islamic calligraphy and its relevance to Turkish graphic art using Latin fonts in the late twentieth century Enis Timuçin Tan University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Tan, Enis Timuçin, A study of Kufic crs ipt in Islamic calligraphy and its relevance to Turkish graphic art using Latin fonts in the late twentieth century, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, Faculty of Creative Arts, University of Wollongong, 1999. http://ro.uow.edu.au/ theses/1749 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact Manager Repository Services: [email protected]. A Study ofKufic script in Islamic calligraphy and its relevance to Turkish graphic art using Latin fonts in the late twentieth century. DOCTORATE OF PHILOSOPHY from UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG by ENiS TIMUgiN TAN, GRAD DIP, MCA FACULTY OF CREATIVE ARTS 1999 CERTIFICATION I certify that this work has not been submitted for a degree to any university or institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by any other person, expect where due reference has been made in the text. Enis Timucin Tan December 1999 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I acknowledge with appreciation Dr. Diana Wood Conroy, who acted not only as my supervisor, but was also a good friend to me. I acknowledge all staff of the Faculty of Creative Arts, specially Olena Cullen, Liz Jeneid and Associate Professor Stephen Ingham for the variety of help they have given to me. -

Ballpoint Basics 2017, Ballpoint Pen with Watercolor Wash, 3 X 10

Getting the most out of drawing media MATERIAL WORLD BY SHERRY CAMHY Israel Sketch From Bus by Angela Barbalance, Ballpoint Basics 2017, ballpoint pen with watercolor wash, 3 x 10. allpoint pens may have been in- vented for writing, but why not draw with them? These days, more and more artists are decid- Odyssey’s Cyclops by Charles Winthrop ing to do so. Norton, 2014, ballpoint BBallpoint is a fairly young medium, pen, 19½ x 16. dating back only to the 1880s, when John J. Loud, an American tanner, Ballpoint pens offer some serious patented a crude pen with a rotat- advantages to artists who work with ing ball at its tip that could only make them. To start, many artists and collec- marks on rough surfaces such as tors disagree entirely with Koschatzky’s leather. Some 50 years later László disparaging view of ballpoint’s line, Bíró, a Hungarian journalist, improved finding the consistent width and tone Loud’s invention using quick-drying of ballpoint lines to be aesthetically newspaper ink and a better ball at pleasing. Ballpoint drawings can be its tip. When held perpendicular to composed of dense dashes, slow con- its surface, Bíró’s pen could write tour lines, crosshatches or rambling smoothly on paper. In the 1950s the scribbles. Placing marks adjacent to one Frenchman Baron Marcel Bich pur- another can create carefully modu- chased Bíró’s patent and devised a lated areas of tone. And if you desire leak-proof capillary tube to hold the some variation in line width, you can ink, and the Bic Cristal pen was born. -

Pencil Eraser (Edited from Wikipedia)

Pencil Eraser (Edited from Wikipedia) SUMMARY An eraser, (also called a rubber outside America, from the material first used) is an article of stationery that is used for removing writing from paper. Erasers have a rubbery consistency and come in a variety of shapes, sizes and colors. Some pencils have an eraser on one end. Less expensive erasers are made from synthetic rubber and synthetic soy-based gum, but more expensive or specialized erasers are vinyl, plastic, or gum-like materials. Erasers were initially made for pencil markings, but more abrasive ink erasers were later introduced. The term is also used for things that remove writing from chalkboards and whiteboards. HISTORY Before rubber erasers, tablets of wax were used to erase lead or charcoal marks from paper. Bits of rough stone such as sandstone or pumice were used to remove small errors from parchment or papyrus documents written in ink. Crustless bread was used as an eraser in the past; a Meiji-era (1868-1912) Tokyo student said: "Bread erasers were used in place of rubber erasers, and so they would give them to us with no restriction on amount. So we thought nothing of taking these and eating a firm part to at least slightly satisfy our hunger." In 1770 English engineer Edward Nairne is reported to have developed the first widely marketed rubber eraser, for an inventions competition. Until that time the material was known as gum elastic or by its Native American name (via French) caoutchouc. Nairne sold natural rubber erasers for the high price of three shillings per half-inch cube. -

19Th Century Writing Activity: Pen &

Lesson Plan: #NoyesArtatHome 19th Century Writing Activity: Pen & Ink Activity based on letters on display in the Noyes Museum’s Estell Empire Exhibition For ages 12 & up Experience with cursive* writing not necessary Assistance from an adult would be helpful. Overview: Round Hand Script: This was the dominant cursive* writing style among 19th century writing “masters,” whose An account book from John Estell’s general store models were engraved on metal. Letters Circa 1836 – 1837 sloped to the right, and thick lines were © Collection of Stockton University produced on the downstrokes using a flexible, straight-edged (not pointed) pen nib (tip). Thin lines were made by using the corner of the nib. Round hand included decorative swirls referred to as “command of hand.” Copperplate: This type of writing was made with a flexible, pointed metal pen. Copperplate script differs from round hand in the gradual swelling of the broad strokes on curved forms and the narrowness of the backstrokes of b, e, and o. Definitions from Britannica.com: https://www.britannica.com/topic/black-letter Project Description: This lesson provides a brief overview of handwriting in the 19th century and a hands-on writing activity. First, paint with a teabag to make “old” looking paper. To write, use a quill** pen with black ink or watered-down paint, or a marker. Try to read and copy the example of 19th century writing. Can you write your own name, or a whole letter to a friend? Supplies: 8.5 x 11” piece of paper A tea bag; preferably a darker tea such as black tea (Lipton, Red Rose) A watercolor brush Your choice of: a quill** pen and black ink, watered-down black paint with a fine-tipped brush, or a black marker (for example: Crayola – “broad line” or Sharpie – “fine point,” the newer, the better) *Cursive writing is a style of writing in which all of the letters in a word are connected. -

WANDA: a Measurement Tool for Forensic Document Examiners Measurement Science and Standards in Forensic Handwri�Ng Analysis, NIST Campus, Conference & Webcast 4./5

A FISH called WANDA, 2013 A FISH called WANDA! WANDA: A Measurement Tool for Forensic Document Examiners Measurement Science and Standards in Forensic HandwriCng Analysis, NIST Campus, Conference & Webcast 4./5. June 2013 Katrin Franke, Department of Computer Science and Media Technology, Gjøvik University College hp://www.nislab.no Forensics Lab 1 A FISH called WANDA, 2013 Katrin Franke, PhD, Professor § Professor of Computer Science, 2010 PhD in ArCficial Intelligence, 2005 MSc in Electrical Engineering, 1994 § Industrial Research and Development (19+ years) Financial Services and Law Enforcement Agencies § Courses, Tutorials and post-graduate Training: Law Enforcement, BSc, MSc, PhD § Chair IAPR/TC6 – Computaonal Forensics, 2008-2012 § IAPR Young InvesCgator Award, 2009 Internaonal Associaon of Paern RecogniCon Forensics Lab 2 kyfranke.com A FISH called WANDA, 2013 Current Affilia7on § Norwegian Information Security Laboratory (NISlab) Department of Computer Science and Media Technology, Gjøvik University College, P.O. Box 191, N-2802 Gjøvik, Norway. § http://www.nislab.no Forensics Lab 3 KyFranke - ICDAR 2007 - Tutorial - Computational Forensics 3 A FISH called WANDA, 2013 Disclaimer § The following slides have been published previously, i.e. § Franke, K., Schomaker, L., Vuurpijl, L., Giesler, S. (2003). FISH-New: A common ground for computer-based forensic writer identification (Abstract). Forensic Science International, Volume 136(S1-S432) p. 84, Proc. 3rd European Academy of Forensic Science Triennial Meeting, Istanbul, Turkey. § Franke, K. (2004). Digital image processing and pattern recognition in the forensic analysis of handwriting (Abstract). In Proc. 6th International Congress of the Gesellschaft für Forensischen Schriftenuntersuchung (GFS), Heidelberg, Germany. § Franke, K., Rose, S. (2004). Ink-deposition model: The relation of writing and ink deposition processes. -

CL4500 - Installation Instructions

Home (/) > Knowledge Base - Home (/knowledgebase/) > KA-01048 Print CL4500 - Installation Instructions Views: 169 Box Contents Check the contents of the box are correct according to the model 4510 4520 1 Front Plate 2 Back Plate 3 Lever Handles 4 Gaskets 5 Sprung Spindle (x1) 6 Spring Spindle (x3) 15/26/60mm (⁄”/ ⁄”/ ⁄”) 7 1.5vAA Batteries (x4) 8 Mortice Latch, Strike and 4 screws 9 Fixing Bolts x 3 incl. spare 10Latch Support Post 11Allen Keys 12Euro profile cylinder escutcheons (x2) 13Double euro profile cylinder & 3 keys 14Cable Connections for REM1 and REM2 15Front Plate Cylinder Keys 16Front Plate Cylinder Cover 17Classroom Function Tailpiece 18Mortice Lock This box should also contain the installation template and getting started guide. Tools Required Power Drill Drill bits CL4510 10mm (⁄”) & 25mm (1”) Drill bits CL4520 10mm (⁄”), 12mm (⁄”), 16mm (⁄”) & 20mm (⁄”) Hammer / mallet Philips screwdriver Chisel 25mm (1") Stanley knife Adhesive tape, pencil, bradawl, tape measure Pliers and hacksaw for cutting bolts Operations Check You should familiarise yourself with the operation of the lock and check that all the parts work properly. Remove the battery cover from the back plate and install the 4 x AA cells supplied. Connect the cables from the front plate and back plate. A BEEP should be heard when you do this. If no BEEP is heard then check that the batteries are correctly installed. Place the long spindle in the front plate socket and using finger grip only, test that the spindle is easily moved 80° in both directions. Leave socket in the centred position. Enter the factory Master Code #12345678. -

C:Documents and Settingsgarymy Documentswordperfect User

Gary & Myrna Lehrer’s Quarterly Illustrated Vintage Pen Catalog [email protected] Issue #54 - March 2010 See the Catalog in full color on the web site. For about a week you’ll need a password for access (be sure to also see what’s remaining from previous Catalogs). WEB SITE PAS SWORD FOR CATALOG #54: (www.gopens.com): BLUE Catalog #54 Feature: Incredible “Extraordinary Pens” Over 260 Items 35+ Manufacturers Represented Some Great Italian Pens Sheaffer, Wahl, Waterman, Parker & more A great group of Montblancs Contact Information: Tel: (203) 389-5295 email: [email protected] Fax: (859) 909-1882 Call until 10:30 PM Eastern Time; Fax anytime We check our email often Subscription Expired: A (1) on your mailing label means your subscription has expired. “Internet Only” renewal is $10. “Hard Copy” Renewal is $25 US and $35 Foreign (see website for details). Received a sample copy? Don’t forget to subscribe ! Please see inside front page for abbreviations and other important information! Gary & Myrna Lehrer 16 Mulberry Road Woodbridge, CT 06525-1717 March 2010 - CATALOG #54 Here’s Some Other Important Information : GIFT CERTIFICATES : Available in any denomination. No extra cost! No expiration! Always fully refundable! REPAIRS - CONSIGNMENT - PEN PURCHASES : We do the full array of pen repairs - very competitively priced. Ask about consignment rates for the Catalog (we reserve the right to turn down consignments), or see the web site for details. We are also always looking to purchase one pen or entire collections. ABBREVIATIONS : Mint - No sign of use Fine - Used, parts show wear Near Mint - Slightest signs of use Good - Well used, imprints may be almost Excellent - Imprints good, writes well, looks great gone, plating wear Fine+ - One of the following: some brassing, Fair - A parts pen some darkening, or some wear ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- LF - Lever Filler HR - Hard Rubber PF - Plunger Filler (ie. -

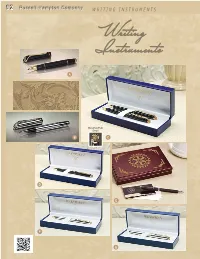

Writing Instruments 1.800.877.8908 93

92 Russell-Hampton Company WRITING INSTRUMENTS www.ruh.com 1.800.877.8908 93 Waterman Pens Detail 92 Russell-Hampton Company www.ruh.com 1.800.877.8908 93 Serving Rotarians Since 1920 A. R66032 Quill® Heritage Roller Ball Pen Features include: newly designed teardrop clip & inlaid feather band, high gloss black lacquer cap, gold accents, fine-point black Roller Ball refill, with full-color slant top Rotary International logo, & handsome display box. Lifetime guarantee. Unit Price $34.95 • Buy 3 $32.95 ea. • Buy 6 $30.95 ea. • Buy 12+ $29.95 ea. B. R66040 Quill® Heritage Roller Ball Pen Elegant teardrop clip and inlaid feather band highlight this beautiful brushed chrome, smooth writing Quill® rollerball pen. Rotary International emblem in crown. Lifetime guarantee. Gift Boxed. Unit Price $34.95 • Buy 3 $33.20 ea. • Buy 6 $31.45 ea. • Buy 12+ $29.70 ea. C. R66012 Waterman® Hemisphere Black Pen & Pencil Set • Classic high gloss black lacquer finish complimented with 23.3-karat gold electroplated clip & trim. Die-struck Rotary emblems affixed to the crowns. Ball pen is fitted with a black ink, medium point refill. Pencil is fitted with 0.5mm lead. Waterman Signature Presentation Blue Box with satin lining. Unit Price $107.95 • Buy 2 $102.50 ea. • Buy 3+ $97.25 ea. D. R66011 Waterman® Hemisphere Black Ball Pen • Same ball pen as sold in above set. Water- man Signature Presentation Blue Box with satin lining. Unit Price $51.95 • Buy 3 $49.35 ea. • Buy 6 $46.85 ea. • Buy 12+ $44.55 ea. -

Technical Description Mechanical Pencil Portfolio

The Mechanical Pencil A Technical Description The mechanical pencil is a reusable wri�ng instrument that uses a lead-advance mechanism to extend rods of graphite lead forward. The mechanical pencil is most commonly used for drawing pictures, designs or symbols, and wri�ng text on paper. Tombow Pencil Co. is recognized for high-quality mechanical pencils, and mul�farious erasers. This document uses the Tombow Mono Graph pencil (as a model) to describe the features and components of a mechanical pencil. Features The mechanical pencil is a precision wri�ng instrument more commonly used for drawing than wooden pencils and uses either dra�ing lead or thin leads. Graphic art, technical drawing, and wri�ng professionals use the mechanical pencil to create a line of constant thickness. (see fig. 1) • Life�me reusable holder • Individual replacemtn of graphite lead rods • Pencil never decreases in size or need to be sharpened • Rubber gripping prevents callus buildup under the middle finger joint The mechanical pencil combines the features of a wooden pencil and a ballpoint pen. It can be held in the palm of a hand and is made of hi-impact plas�c or metal. Approximately one-third of the mechanical pencil is wrapped with so� black rubber for gripping between the thumb, index, and middle finger while wri�ng or drawing. The clamp holder (or clip), located at the top, can slide into a T-shirt breast pocket allowing for hands-free carrying and easy access. Types There are three basic types of mechanisms used to extend the graphite lead in the mechanical pencil. -

Stylos Writing Instruments Since 1981 a Fountain Pen Is One of Those Rare Objects Which Connects with Us on So Many Levels

stylos writing instruments since 1981 A fountain pen is one of those rare objects which connects with us on so many levels. In our most creative mode, it is an extension of our mind which through gestures of our hand convert random thoughts into intelligible concepts, ideas or expressions. Every time we use a writing instrument - we write code. Sometimes people understand it. Sometimes there are layers in the meaning of the words we write. Often, we give away more in the style and stroke of our writing than in the actual words themselves. In many cultures, the written letter and word is considered “art”. I take every opportunity to infuse art into everyday objects. With pens it’s even more tactile sensual and very personal. STYLOS is sculpture. It’s a little “kiss of art” you can carry with you. kostas metaxas the heart of a great pen is the nib... Introducing the world’s first universal nib system - change from a premium German “BOCK” , “SCHMIDT” [YOWO] steel, titanium, gold or palladium nib, or rollerball, fineliner in a few seconds. stylos titanium stylos titanium stylos titanium set stylos titanium set - red capsule stylos titanium a precious nib housed in a sensual sculpture STYLOS TITANIUM is about simplicity and movement. There is a French saying which best explains it: “Faire vivre le trait.” - Make a line come alive. STYLOS TITANIUM is the sublime “body” of a fine writing instrument. The heart of a fine writing instrument is the nib. Made from different noble materials, it has the ability to influence your relationship between mind, hand and paper. -

New Summary Report - 26 June 2015

New Summary Report - 26 June 2015 1. How did you find out about this survey? Other 17% Email from Renaissance Art 83.1% Email from Renaissance Art 83.1% 539 Other 17.0% 110 Total 649 1 2. Where are you from? Australia/New Zealand 3.2% Asia 3.7% Europe 7.9% North America 85.2% North America 85.2% 553 Europe 7.9% 51 Asia 3.7% 24 Australia/New Zealand 3.2% 21 Total 649 2 3. What is your age range? old fart like me 15.4% 21-30 22% 51-60 23.3% 31-40 16.8% 41-50 22.5% Statistics 21-30 22.0% 143 Sum 20,069.0 31-40 16.8% 109 Average 36.6 41-50 22.5% 146 StdDev 11.5 51-60 23.3% 151 Max 51.0 old fart like me 15.4% 100 Total 649 3 4. How many fountain pens are in your collection? 1-5 23.3% over 20 35.8% 6-10 23.9% 11-20 17.1% Statistics 1-5 23.3% 151 Sum 2,302.0 6-10 23.9% 155 Average 5.5 11-20 17.1% 111 StdDev 3.9 over 20 35.8% 232 Max 11.0 Total 649 4 5. How many pens do you usually keep inked? over 10 10.3% 7-10 12.6% 1-3 40.7% 4-6 36.4% Statistics 1-3 40.7% 264 Sum 1,782.0 4-6 36.4% 236 Average 3.1 7-10 12.6% 82 StdDev 2.1 over 10 10.3% 67 Max 7.0 Total 649 5 6.