Harold Frederic's the Damnation of Theron Ware: a Study Guide with Annotated Bibliography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Super Satan: Milton’S Devil in Contemporary Comics

Super Satan: Milton’s Devil in Contemporary Comics By Shereen Siwpersad A Thesis Submitted to Leiden University, Leiden, the Netherlands in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MA English Literary Studies July, 2014, Leiden, the Netherlands First Reader: Dr. J.F.D. van Dijkhuizen Second Reader: Dr. E.J. van Leeuwen Date: 1 July 2014 Table of Contents Introduction …………………………………………………………………………... 1 - 5 1. Milton’s Satan as the modern superhero in comics ……………………………….. 6 1.1 The conventions of mission, powers and identity ………………………... 6 1.2 The history of the modern superhero ……………………………………... 7 1.3 Religion and the Miltonic Satan in comics ……………………………….. 8 1.4 Mission, powers and identity in Steve Orlando’s Paradise Lost …………. 8 - 12 1.5 Authority, defiance and the Miltonic Satan in comics …………………… 12 - 15 1.6 The human Satan in comics ……………………………………………… 15 - 17 2. Ambiguous representations of Milton’s Satan in Steve Orlando’s Paradise Lost ... 18 2.1 Visual representations of the heroic Satan ……………………………….. 18 - 20 2.2 Symbolic colors and black gutters ……………………………………….. 20 - 23 2.3 Orlando’s representation of the meteor simile …………………………… 23 2.4 Ambiguous linguistic representations of Satan …………………………... 24 - 25 2.5 Ambiguity and discrepancy between linguistic and visual codes ………... 25 - 26 3. Lucifer Morningstar: Obedience, authority and nihilism …………………………. 27 3.1 Lucifer’s rejection of authority ………………………..…………………. 27 - 32 3.2 The absence of a theodicy ………………………………………………... 32 - 35 3.3 Carey’s flawed and amoral God ………………………………………….. 35 - 36 3.4 The implications of existential and metaphysical nihilism ……………….. 36 - 41 Conclusion ……………………………………………………………………………. 42 - 46 Appendix ……………………………………………………………………………… 47 Figure 1.1 ……………………………………………………………………… 47 Figure 1.2 ……………………………………………………………………… 48 Figure 1.3 ……………………………………………………………………… 48 Figure 1.4 ………………………………………………………………………. -

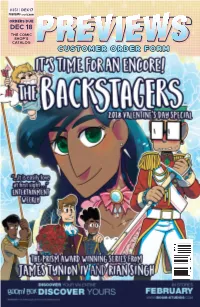

Customer Order Form

#351 | DEC17 PREVIEWS world.com ORDERS DUE DEC 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM CUSTOMER 601 7 Dec17 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 11/9/2017 3:19:35 PM Dec17 Dark Horse.indd 1 11/9/2017 9:27:19 AM KICK-ASS #1 (2018) INCOGNEGRO: IMAGE COMICS RENAISSANCE #1 DARK HORSE COMICS GREEN LANTERN: EARTH ONE VOLUME 1 HC DC ENTERTAINMENT MATA HARI #1 DARK HORSE COMICS VS. #1 IMAGE COMICS PUNKS NOT DEAD #1 IDW ENTERTAINMENT THE BRAVE AND THE BOLD: BATMAN AND WONDER DOCTOR STRANGE: WOMAN #1 DAMNATION #1 DC ENTERTAINMENT MARVEL COMICS Dec17 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 11/9/2017 3:15:13 PM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Jimmy’s Bastards Volume 1 TP l AFTERSHOCK COMICS Dreadful Beauty: The Art of Providence HC l AVATAR PRESS INC 1 Jim Henson’s Labyrinth #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS WWE #14 l BOOM! STUDIOS Dejah Thoris #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT 1 Pumpkinhead #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Is This Guy For Real? GN l :01 FIRST SECOND Battle Angel Alita: Mars Chronicle Volume 1 GN l KODANSHA COMICS Dead of Winter Volume 1: Good Good Dog GN l ONI PRESS INC. Devilman: The Classic Collection Volume1 GN l SEVEN SEAS ENTERTAINMENT LLC Your Black Friend and Other Strangers HC l SILVER SPROCKET Bloodborne #1 l TITAN COMICS Robotech Archive Omnibus Volume 1 GN l TITAN COMICS Disney·Pixar Wall-E GN l TOKYOPOP Bloodshot: Salvation #6 l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT LLC BOOKS Doorway to Joe: The Art of Joe Coleman HC l ART BOOKS Neon Visions: The Comics of Howard Chaykin SC l COMICS Drawing Cute With Katie Cook SC l HOW-TO 2 Action Presidents -

New Comics & TP's for the Week of 3/07/18

Infinity Countdown #1 Lim Wraparound Var New Comics & TP's Injustice 2 #21 Jetsons #5 for the Week of 3/07/18 Justice League #40 Justice League of America TP Vol 03 Panic Microverse Rebirth /13 Action / Adventure Koshchei the Deathless #3 Abbott #1 2nd Ptg Marvel's Ant-Man and Wasp Prelude #1 Assassinistas #3 Nightwing #40 Assassins Creed Origins #1 Rasputin Voice of Dragon #5 Dodge City #1 Rise of Black Panther #3 East of West #36 Rogue & Gambit #3 Elsewhere #5 Shade the Changing Woman #1 Fix #11 Shadow Batman #6 Galaktikon #5 She-Hulk #163 Ghostbusters Annual 2018 Spider-Man #238 Giant Days #36 Super Sons TP Vol 02 Planet of the Capes Rebirth Gravediggers Union #5 Superman #42 Highest House #1 Thanos #13 3rd Ptg Highest House #1 Var Ed True Believers Venom Sybiosis #1 I Hate Fairyland #17 True Believers Venom vs. Spider-Man #1 Incognegro Renaissance #2 Venom #163 Jem & the Holograms Dimensions #4 Wild Storm #12 Monstro Mechanica #4 X-Men Gold #23 nd Rick & Morty Presents the Vindicators #1 X-Men Red #1 2 Ptg Scales & Scoundrels #7 X-Men Red #2 Spider King #1 Strangers in Paradise XXV #2 Horror Tick 2018 #3 Frankenstein Alive Alive #4 Über Invasion #12 Gideon Falls #1 Wicked & Divine #34 Jughead the Hunger #4 October Faction Supernatural Dreams #1 Superhero Van Helsing vs. Robyn Hood #3 Amazing Spider-Man #795 2nd Ptg Walking Dead #177 Amazing Spider-Man #797 Walking Dead TP Vol 29 Amazing Spider-Man #797 Kuder Young Guns Var Atomic Robo Spectre of Tomorrow #5 Kid’s Avengers #683 Adventure Time #74 Bane Conquest #10 Archie and Me Comics -

NEW THIS WEEK from MARVEL... Infinity Countdown Prime #1 Amazing Spider-Man #796 Avengers #681 Mighty Thor #704 Daredevil #599

NEW THIS WEEK FROM MARVEL... Infinity Countdown Prime #1 Amazing Spider-Man #796 Avengers #681 Mighty Thor #704 Daredevil #599 Punisher Platoon #6 (of 6) Doctor Strange Damnation #1 (of 4) Astonishing X-Men #8 X-Men Gold #22 Star Wars Doctor Aphra #17 Deadpool vs. Old Man Logan #5 (of 5) Incredible Hulk #713 Defenders #10 Venom #162 Tales of Suspense #102 Black Panther Annual #1 Avengers #676 (2nd print) Generation X #87 Luke Cage #170 Old Man Hawkeye #1 (of 12) 2nd PTG Monsters Unleashed #11 NEW THIS WEEK FROM DC... Batman #41 Brave & the Bold Batman & Wonder Woman #1 (of 6) Justice League #39 Damage #2 Superman #41 Batman / Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles II #4 (of 6) Batman and the Signal #2 (of 3) Super Sons #13 Nightwing #39 Batman Sins of the Father #1 (of 6) Trinity #18 Cave Carson / Swamp Thing Special #1 Aquaman #33 Green Lanterns #41 Wonder Woman / Conan #6 (of 6) Harley Quinn #38 Batwoman #12 Deathbed #1 (Vertigo) DC Universe by Neil Gaiman GN Injustice 2 #20 Mother Panic Vol. 2 GN Young Justice Vol. 2 GN Bombshells United #12 Future Quest Presents #7 NEW THIS WEEK FROM IMAGE... Hit-Girl #1 Monstress #14 Moonshine #7 Ice Cream Man #2 Eternal Empire #7 Birthright #30 Descender #27 Evolution #4 Sex Criminals #22 Twisted Romance #3 (of 4) Maestros #5 Family Trade #5 Further Adventures of Nick Wilson #2 (of 5) Multiple Warheads Ghost Throne One-Shot Postal Mark #1 (One-Shot) Redlands #6 NEW FROM OTHER PUBLISHERS... Quantum & Woody #3 Ninjak vs. -

Club Add Form

O GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY: EARTH O CAPTAIN TRIPS PREMIERE HC SHALL OVERCOME PREMIERE HC Collects Collecting THE STAND: CAPTAIN TRIPS #1-5. MARVEL SUPER-HEROES #18, MARVEL TWO-IN- 160 PGS...$24.99 ONE #4-5, GIANT-SIZE DEFENDERS #5 and DE- O MARVEL MASTERWORKS: FANTASTIC FENDERS #26-29.176 PGS./Rated A ...$19.99 FOUR VOL. 1 TPB Collecting THE FANTASTIC O MARVEL ADVENTURES THE AVENGERS STAR WARS ADVENTURES VOL.1 Digest on-going FOUR #1-10. 272 PGS...$24.99 VOL. 8: THE NEW RECRUITS DIGEST O MARVEL MASTERWORKS: GOLDEN AGE Collecting MARVEL ADVENTURES THE AVEN- Before they ever met Luke Skywalker or Princess Leia, Han Solo and Chewbacca had MARVEL COMICS VOL. 4 HC Collecting MARVEL GERS #28-31. 96 PGS./All Ages ...$9.99 already lived a lifetime of adventures. In this action-packed tale, Han and Chewie are MYSTERY COMICS #13-16. O SKRULLS VS. POWER PACK DIGEST caught between gangsters and the Empire, and their only help is Han's former partner- 280 PGS ...$59.99 Collecting SKRULLS VS. POWER PACK #1-4 O MARVEL MASTERWORKS: THE INCREDI- 96 PGS./All Ages ...$9.99 -who may be worse than either! This is a new series of GNs designed for of all ages! BLE HULK VOL. 5 HCCollecting THE INCREDIBLE O MINI MARVELS: SECRET INVASION DIGEST HULK #111-121.240 PGS..$54.99 96 PGS./All Ages ...$9.99 SOUL KISS #1 (of 5) O WOLVERINE OMNIBUS VOL. 1 HC Collecting O SECRET INVASION: FRONT LINE TPB $14.99 STEVEN T. SEAGLE comes to Image for SOUL KISS - the story of a woman with MARVEL COMICS PRESENTS #1-10, #72-84; IN- O SECRET INVASION: BLACK PANTHER $12.99 vengeance on her mind and damnation on her lips. -

Marvel January – April 2021

MARVEL Aero Vol. 2 The Mystery of Madame Huang Zhou Liefen, Keng Summary THE MADAME OF MYSTERY AND MENACE! LEI LING finally faces MADAME HUANG! But who is Huang, and will her experience and power stop AERO in her tracks? And will Aero be able to crack the mystery of the crystal jade towers and creatures infiltrating Shanghai before they take over the city? COLLECTING: AERO (2019) 7-12 Marvel 9781302919450 Pub Date: 1/5/21 On Sale Date: 1/5/21 $17.99 USD/$22.99 CAD Paperback 136 Pages Carton Qty: 40 Ages 13 And Up, Grades 8 to 17 Comics & Graphic Novels / Superheroes CGN004080 Captain America: Sam Wilson - The Complete Collection Vol. 2 Nick Spencer, Daniel Acuña, Angel Unzueta, Paul Re... Summary Sam Wilson takes flight as the soaring Sentinel of Liberty - Captain America! Handed the shield by Steve Rogers himself, the former Falcon is joined by new partner Nomad to tackle threats including the fearsome Scarecrow, Batroc and Baron Zemo's newly ascendant Hydra! But stepping into Steve's boots isn't easy -and Sam soon finds himself on the outs with both his old friend and S.H.I.E.L.D.! Plus, the Sons of the Serpent, Doctor Malus -and the all-new Falcon! And a team-up with Spider-Man and the Inhumans! The headline- making Sam Wilson is a Captain America for today! COLLECTING: CAPTAIN AMERICA (2012) 25, ALL-NEW CAPTAIN AMERICA: FEAR HIM (2015) 1-4, ALL-NEW CAPTAIN AMERICA (2014) 1-6, AMAZING SPIDERMAN SPECIAL (2015) 1, INHUMAN SPECIAL (2015) 1, Marvel ALL-NEW CAPTAIN AMERICA SPECIAL (2015) 1, CAPTAIN AMERICA: SAM WILSON (2015) 1-6 9781302922979 Pub Date: 1/5/21 On Sale Date: 1/5/21 $39.99 USD/$49.99 CAD Paperback 504 Pages Carton Qty: 40 Ages 13 And Up, Grades 8 to 17 Comics & Graphic Novels / Superheroes CGN004080 Marvel January to April 2021 - Page 1 MARVEL Guardians of the Galaxy by Donny Cates Donny Cates, Al Ewing, Tini Howard, Zac Thompson, .. -

University Microfilms International 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 USA St

HAROLD FREDERIC AS A PURVEYOR OF AMERICAN MYTH: AN APPROACH TO HIS NOVELS Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Witt, Stanley Pryor, 1938- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 11/10/2021 06:56:39 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/290424 INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. -

WILLIAM STYRON and JOSEPH HELLER William

r\c». ñ TRAGIC AND COMIC MODES IN TWENTIETH CENTURY AMERICAN LITERATURE: WILLIAM STYRON AND JOSEPH HELLER William Luttrell A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY June 1969 Approved by Doctoral Committee /»í J Adviser Dg$artment of English Graduate School Representative ABSTRACT William Styron and Joseph Heller are important contemporary American writers who can be associated with a certain "climate of opin ion" in the twentieth century. The intellectual basis for this climate of opinion is that the world we know today, metaphysically, historical ly, scientifically, and socially, is one that does not admit to a secure and stable interpretation. Within such a climate of opinion one hesi tates to enumerate metaphysical truths about the universe; one doubts historical eschatology, except perhaps in a diabolical sense; one speaks scientifically in terms of probability and the statistics of randomness rather than absolute order; and one analyzes social problems in terms of specific values in specific situations rather than from an unchanging and absolute frame of reference. Indeed, it is because of a diminishing hope of achieving an absolute or even satisfying control over the world that many have come to live with contingency as a way of life, and have little reason to believe that their partially articulated values rever berate much beyond themselves. Through their fictional characters William Styron and Joseph Heller are contemporary observers of this climate of opinion. Styron reveals in his novels a vision of man separated from his familiar values and unable to return to them. -

Reasonable Damnation: How Jonathan Edwards Argued for the Rationality of Hell

JETS 38/1 (March 1995) 47-56 REASONABLE DAMNATION: HOW JONATHAN EDWARDS ARGUED FOR THE RATIONALITY OF HELL BRUCE W. DAVIDSON* Controversy about the existence and nature of hell is not new, but recent years have seen a revival of it, such that even U.S. News and World Report carried a cover story on the topic.1 It is especially surprising to see some prominent evangelicals coming forward to dispute the traditional, orthodox understanding of this doctrine, among them J. R. W. Stott and C. Pinnock. Accordingly various popular volumes have appeared, some of which Chris- tianity Today reviewed under the title "A Kinder, Gentler Damnation."2 En- countering these discussions, the student of theological history experiences something like déjà vu. He has heard it all before. As in many great theo- logical controversies, including the free-will/predestination debate, oppo- nents have once again appeared to wage the same ideological battles, making use of many of the same arguments. Modern controversialists may have little new to add to a very old debate. That becomes clear when we ex- amine the thorough treatment of the doctrine of damnation by the American theologian Jonathan Edwards, whose incisive defense of the traditional view has perhaps never been successfully answered. New England pastor, theologian, and a leader of the great awakening, Edwards (1703-1758) is probably best known for his sermon Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God. An excerpt from this sermon is often found in American literature textbooks and anthologies, the selected passage usually being his comparison of the sinner to a spider being held precari- ously over the flames of hell.3 As a result, most people who know Edwards probably think of him as a crude fanatic trying to terrify his poor parish- ioners with lurid images of eternal fire. -

The Howellsian, Volume 9, Number 1 (Spring 2006) Page 1

The Howellsian, Volume 9, Number 1 (Spring 2006) Page 1 New Series Volume 9, Number 1 The Howellsian Spring 2006 A Message from the Editor Inside this issue: information by Donna Campbell on the Although we can hardly believe Society’s web site, and 5) recent criticism From the Editor 1 that winter is nearly over because so little on W. D. Howells. time seems to have passed since we mailed out the Autumn issue of The How- Howells Essay Prize 1 ellsian last fall, we’re already looking to- Sanford E. Marovitz, Editor ward San Francisco. The ALA confer- ence will be held May 25-28, again at the Howells Society Business: 2 Hyatt Regency in Embarcardero Center, • Panels for ALA 2006 where the William Dean Howells Society • New Howells-l Discussion List will next meet. A program arranged by Claudia Stokes, printed below, will be Patrick K. Dooley, “William Dean 3 Howells and Harold Frederic” presented. We look forward to seeing you all there. Annotated Bibliography of Recent 9 Work on Howells Following our editorial message, this issue of The Howellsian includes:1) The W. D. Howells Society Web Site 11 the 2006 program for the Society’s two sessions at the forthcoming ALA confer- ence, 2) the announcement of an in- augural prize to be awarded annu- William Dean Howells in 1907 ally by the Society beginning this year, 3) an essay by Patrick K. Doo- In the next issue: ley (Saint Bonaventure Univ): “William • Review of Master and Dean: Dean Howells and Harold Frederic,” 4) The Literary Criticism of Henry James and William Dean Annual Howells Essay Prize to be Awarded Howells by Robert Davidson • Howells Society Business As announced last fall, this year for the first time, an annual prize will be Meeting awarded by the William Dean Howells Society for the best paper on Howells presented • Call for Papers for ALA 2007 at the ALA conference. -

Ebook Download Spider-Man 2099 Vol. 5

SPIDER-MAN 2099 VOL. 5: CIVIL WAR II PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Peter David | 136 pages | 31 Jan 2017 | Marvel Comics | 9781302902810 | English | New York, United States Spider-man 2099 Vol. 5: Civil War Ii PDF Book Though I liked seeing all the future heroes! Universal Conquest Wiki. Heather rated it it was ok Feb 04, Loading Author Notes Captain Marvel, the Avengers, and the Ultimates tracked down Tony after convincing the Inhumans to let them deal with Tony by themselves. In addition, the law stipulates that all super-beings who do not work for the government are automatically outlawed. Buy It Now. But how has his native timeline become so different from the one he left behind? Spider-Man Vol 3. A real turd, to the tee. Land Variant. Universe s. Ulysses says that Karnak has taught him how to step back from it when it happens, like when you know that you are dreaming, and is not as bad as before. Maria Hill told Iron Man and his allies that they were under arrest for attacking the Triskelion. Original Title. Tony Stark's body was taken shortly after to the Triskelion, where Beast discovered that secret biological enhancements in Tony's body were the only thing that had kept it alive. Paperback , Trade , pages. Peter Parker Variant. Fueled by grief, Iron Man infiltrated New Attilan and kidnapped the young Inhuman in order to properly study and analyse his powers, but not before entering into a brief scuffle against Queen Medusa, Crystal , and Karnak. Travel Foreman. Tony also brought into question the morality of stopping and punishing somebody for a disaster they could potentially do, and might not even know they'd do, however, Carol remained adamant in using Ulysses, considering it had worked perfectly in stopping the Celestial. -

01Dickstein Intro 1-14.Qxd

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. INTRODUCTION: A MIRROR IN THE ROADWAY Once there was a common assumption that along with everything else that gave meaning to literature—the mastery of language and form, the personal- ity of the author, the moral authority, the degree of originality, the reactions of the reader—hardly anything could be more central to it than the text’s inter- play with the “real world.” Literature, especially fiction, was unapologetically about the life we live outside of literature, the social life, the emotional life, the physical life, the specific sense of time and place. This was especially true after the growth of literary realism in England in the eighteenth century with Defoe and Richardson; in France in the early nineteenth century with Stend- hal and Balzac; in Russia at midcentury with Tolstoy; in England again with George Eliot, Dickens, and Trollope; and finally in America with Mark Twain, Henry James, and William Dean Howells, who became the tireless promoter of a whole school of younger realists. Much as we may still enjoy their work as effective storytelling, readily adaptable to other media, the main assumptions of these writers about the novel and the world around it are now completely out of fashion. That is, everywhere except among ordinary readers. Since the modernist period and especially in the last thirty years, a tremendous gap has opened up between how most readers read, if they still read at all, and how critics read, or how they theorize about reading.