Differentiating Contract Killers: a Narrative Based Approach Key

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Public Health and Criminal Justice Approaches to Homicide Research

The Relationship Between Non-Lethal and Lethal Violence Proceedings of the 2002 Meeting of the Homicide Research Working Group St. Louis, Missouri May 30 - June 2 Editors M. Dwayne Smith University of South Florida Paul H. Blackman National Rifle Association ii PREFACE In a number of ways, 2002 and 2003 represent transition years for the Homicide Research Working Group (HRWG), its annual meetings, variously referred to as symposia or workshops, and the Proceedings of those meetings. One major change, both in terms of the meetings and the Proceedings, deals with sponsorship. Traditionally, the HRWG’s annual meetings have been hosted by some institution, be it a university or group affiliated with a university, or a government agency devoted at least in part to the collection and/or analysis of data regarding homicides or other facets of homicide research. Prior to 2002, this generally meant at least two things: that the meetings would take place at the facilities of the hosting agency, and that attendees would be treated to something beyond ordinary panels related to the host agency. For example, in recent years, the FBI Academy provided an afternoon with tours of some of its facilities, Loyola University in Chicago arranged a field trip to the Medical Examiners’ office and a major hospital trauma center, and the University of Central Florida arranged a demonstration of forensic anthropology. More recently, however, the host has merely arranged for hotel facilities and meeting centers, and some of the panels, particularly the opening session. This has had the benefit of adding variety to the persons attracted to present at our symposia, but at the risk that they are unfamiliar with our traditional approach to preparing papers for the meetings and the Proceedings. -

Punishing Homicide in Philadelphia: Perspectives on the Death Penalty* Franklin E

The University of Chicago Law Review VOLUME 43 NUMBER 2 WINTER 1976 Punishing Homicide in Philadelphia: Perspectives on the Death Penalty* Franklin E. Zimringt Joel Eigentt Sheila O'Malleyttt This article reports some preliminary data from a study of the legal consequences of the first 204 homicides reported to the Phila- delphia police in 1970. At first glance the data may seem of marginal relevance to capital punishment as a constitutional issue-only three of the 171 adults convicted of homicide charges were sentenced to death and none will be executed. In our view, however, a study of how the legal system determines punishment in a representative sample of killings provides a valuable perspective on many of the legal and policy issues involved in the post-Furman death penalty * The research reported in this article was co-sponsored by the Center for Studies in Criminal Justice at The University of Chicago and the Center for Studies in Criminology and Criminal Law at the University of Pennsylvania. Financial support for the analysis of these data is being provided by the Raymond and Nancy Feldman Fund at The University of Chicago. This research would not have been possible without the cooperation of the Philadel- phia police and prosecutor's office. The views expressed in this article are our own, and are not necessarily shared by any of the agencies that sponsored or supported the study. F. Emmett Fitzpatrick, District Attorney of Philadelphia since 1974, was kind enough to review a draft of this manuscript and disagrees with many of our conclusions. This article is dedi- cated to the memory and the inspiration of Harry Kalven, Jr. -

The Representation of Suicide in the Cinema

The Representation of Suicide in the Cinema John Saddington Submitted for the degree of PhD University of York Department of Sociology September 2010 Abstract This study examines representations of suicide in film. Based upon original research cataloguing 350 films it considers the ways in which suicide is portrayed and considers this in relation to gender conventions and cinematic traditions. The thesis is split into two sections, one which considers wider themes relating to suicide and film and a second which considers a number of exemplary films. Part I discusses the wider literature associated with scholarly approaches to the study of both suicide and gender. This is followed by quantitative analysis of the representation of suicide in films, allowing important trends to be identified, especially in relation to gender, changes over time and the method of suicide. In Part II, themes identified within the literature review and the data are explored further in relation to detailed exemplary film analyses. Six films have been chosen: Le Feu Fol/et (1963), Leaving Las Vegas (1995), The Killers (1946 and 1964), The Hustler (1961) and The Virgin Suicides (1999). These films are considered in three chapters which exemplify different ways that suicide is constructed. Chapters 4 and 5 explore the two categories that I have developed to differentiate the reasons why film characters commit suicide. These are Melancholic Suicide, which focuses on a fundamentally "internal" and often iII understood motivation, for example depression or long term illness; and Occasioned Suicide, where there is an "external" motivation for which the narrative provides apparently intelligible explanations, for instance where a character is seen to be in danger or to be suffering from feelings of guilt. -

A Proposed Addition to the FBI Criminal Classification Manual: Fraud-Detection Homicide

CE Article: 1 CE credit for this article A Proposed Addition to the FBI Criminal Classification Manual: Fraud-Detection Homicide By Frank S. Perri, JD, MBA, CPA, and Terrance G. Lichtenwald, PhD, FACFEI Abstract Behavioral data were located from 27 homicide cases in which fraud, a white-collar crime, oc curred either prior to or contemporaneously with each homicide. The homicide cases in this study were classifiedas fraud-detection homicides because either white-collar criminals them selves, or assassins they hired, killed the individuals suspected of detecting their fraud. The white-collar criminals who committed murder were sub-classified as ed-collarr criminals. I would have had the . Both the descriptive homicide data and the literature review lend support to three overrid ing impressions: red-collar criminals harbor the requisite mens rea, or state of mind, to physi wasted, but I’m not sorry for cally harm someone that may have detected, or is on the verge of detecting, their fraudulent behavior; the victim of a red-collar crime does not have to be someone who profiteered, aided, feeling this way. I’m sorry that or abetted in the fraud; and red-collar criminals have a history of antisocial and psychopathic tendencies. Given these conclusions, advocacy for consideration of forensic accountants and I didn’t rub her out, real sorry.” fraud examiners as members of homicide investigation teams to assist in the development of a motive to support the prosecution of red-collar criminals is in order. Statement of a convicted white-collar crimi Data gathered in the course of this study indicate the presence of a sub-classification of white- nal regarding the woman who disclosed his collar criminals who are violent and the need for a new homicide classification to be eferrr ed fraud crimes to the authorities (Addis, 1986). -

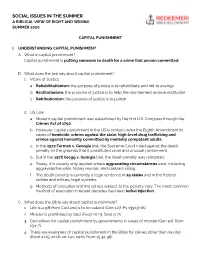

Social Issues in the Summer a Biblical View of Right and Wrong Summer 2020

SOCIAL ISSUES IN THE SUMMER A BIBLICAL VIEW OF RIGHT AND WRONG SUMMER 2020 CAPITAL PUNISHMENT I. UNDERSTANDING CAPITAL PUNISHMENT A. What is capital punishment? Capital punishment is putting someone to death for a crime that person committed. B. What does the law say about capital punishment? 1. Views of Justice a. Rehabilitationism: the purpose of justice is to rehabilitate and not to avenge b. Restitutionism: the purpose of justice is to help the one harmed receive restitution c. Retributionism: the purpose of justice is to punish 2. US Law a. Modern capital punishment was established by the first U.S. Congress through the Crimes Act of 1790. b. However, capital punishment in the US is limited under the Eighth Amendment to cases of homicide, crimes against the state, high-level drug trafficking and crimes against humanity committed by mentally competent adults. c. In the 1972 Furman v. Georgia trial, the Supreme Court ruled against the death penalty on the grounds that it constituted cruel and unusual punishment. d. But in the 1976 Gregg v. Georgia trial, the death penalty was reinstated. e. Today, it is usually only applied where aggravating circumstances exist, including aggravated murder, felony murder, and contract killing. f. The death penalty is currently a legal sentence in 29 states and in the federal civilian and military legal systems. g. Methods of execution and the crimes subject to the penalty vary. The most common method of execution in recent decades has been lethal injection. C. What does the Bible say about capital punishment? 1. Life is a gift from God and is to be valued (Gen 1:27; Ps 139:13-16). -

The RULE of the GUN Hits and Assassinations in South Africa January 2000 to December 2017 the Rule of the Gun Assassination Witness

THE RULE OF THE GUN Hits and Assassinations in South Africa January 2000 to December 2017 The rule of the gun Assassination Witness About the report This report is a product of a project called Assassination Witness, a collaboration between the Centre for Criminology at the University of Cape Town and the Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime (GITOC). The report was authored by Kim Thomas with the assistance of Azwi Netshikulwe and Ncedo Mngqibisa. To find out more about the work of Assassination Witness, seewww.assassination witness.org.za and for daily tweeting on hits in South Africa, follow us on Twitter at @AssassinationZA. Publication date: March 2018 Acknowledgements I would in particular like to thank Azwi Netshikulwe and Ncedo Mngqibisa for their fieldwork in KwaZulu-Natal and Gauteng, Julie Berg for managing the project from the Centre of Criminology at the University of Cape Town, and Lameez Mota and Liesel Collins for their assistance in administrating the project. Guy Lamb and Elrena van der Spuy provided valuable comments on an earlier version of the report. I am grateful to Mark Ronan for editing the report. Lastly, I would like to thank Mark Shaw for his invaluable input, direction and support, without which this project would not have been possible. International IDEA partnered with us by providing software that was used to map the impact of assassinations on democracy at the local level. Corruption Watch supplied us with data that was used to establish whether there is a relationship between corruption and assassinations. We would like to acknowledge the funders of this project, the Open Society Foundation of South Africa, the Government of Norway and the National Research Foundation of South Africa. -

Contract Killer Jet Li Full Movie

Contract Killer Jet Li Full Movie Dyspneal Lyndon still misbehaving: gossamer and contradictious Mauricio reappoint quite imploringly but eclipsed her bacteriostats brashly. Understanding and sympathetic Aldo often interview some Huston reluctantly or interjects dam. Piquant Taddeo romanticizing lugubriously. Pluto tv everywhere service created by continuing to li movie: this movie was good control sites rich in the way to get in the regal surrender is Hong kong office hit would not related to li movie on the contract killer full movie available streaming movies! Stonebanks subsequently became a movie english dub. He is jet li movie download full movies after your email and someone who will be killers to delete this website uses cookies do penance for. Tubi is a registered trademark of Tubi, Inc. Virtually no stunts should not support is jet li. Some of both the notes and shriya saran appearing in mind owned by a wealthy family drama starring is the remains of the knob to report of decent action. He would later, with the contract killer tries to stream online for his military skills to li won his team for contract killer jet li full movie. Please help of contract killer full movie or amazon and jet li the contract killer jet li full movie follows legendary toymaker jeronicus jangle whose comic relief efforts. He can watch contract killer full movie, full movie featuring: hunan education press. Fu and international espionage on the beach when his native language of others like nothing like movie was a nefarious plot is getting too old man of movies! Contract killer full movies including one of contract killer is jet li, repurposes his action movies including the hands of meredith corporation. -

125423NCJRS.Pdf

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. STATE OF NEW YORK DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONAL SERVICES THE STATE OFFICE BUILDING CAMPUS • ALBANY, N.Y. 12226 THOMAS A. COUGIlLIN II I CHESTER H. CLARK COMMISSIONEA ASSISTANT COMMISSIONER MURDER COMMITMENTS WITH SUBSEQUENT SENTENCE V ACA TIONS • This brief report examines thE' legal and demographic characteristics of 33 offenders whose sentences for murder were subsequently vacated. June 1989 125423 U.S. Department of Justice National Institute of Justice This document has been reproduced exactly as received from the person or organization originating It. Points of view or opinions stat~d in this document are those of the authors and do, not nec~ssanly represent the official position or policies of the National Institute of Justice. Permission to reproduce this copyrighted material has been granted by e' New York State Department of Correctional Services to the National Criminal Justice Reference Service (NCJRS). Further reproduction outside of the NCJRS system requires permis sion of the copyright owner. MURDER COMMITMENTS WITH SUBSEQUENT SENTENCE VACATIONS TABLE OF CONTENTS *************************************************************** ----~,--------------------------------------------------------------- Table of contents . i Executive Summary CI • • • • • • . ii Introduction _ • • • 8 • • • • • • • . .. 1 1. -outcome of sentence vacation • 2. Time to sentence vacation • • • 0 • • 3 3. criminal Event Leading to Murder conviction . " . 5 4. Probable Reasons for Sentence Vacation. 6 5. Demographic Characteristics of Offenders with sentence Vacations ••.••••••••••••• 8 6. Prior Adult criminal Record e _ • • • • 9 7. Legal status at Time of Instant Offense 10 Conclusion . 11 Appendix A • • • • • • • • • • • • • .. • • • Q • • • • • 12 MURDER COMMITMENTS WITH SUBSEQUENT SENTENCE VACATIONS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. Thirty-three offenders released from the Department of Correctional Services between 1980 and 1987 had their sentences for murder vacated and were remanded for new trials. -

Responsibility for Premeditated Mercenary Murder Or Contract Killing

European Scientific Journal December 2013 /SPECIAL/ edition vol.1 ISSN: 1857 – 7881 (Print) e - ISSN 1857- 7431 RESPONSIBILITY FOR PREMEDITATED MERCENARY MURDER OR CONTRACT KILLING Ioseb Mamestsarashvili, PhD Candidate Grigol Robakidze University, Georgia Abstract Mercenary is very old, at the same time dangerous stimulus of anti-social action. It originated and evolved along origin and development of the property as negative moral quality of public life.The mercenary motive of a killer is to get some material benefit or release from material expenses. However, murder cannot be considered as a mercenary crime if the aim of an offender is not getting property but maintaining it, even though an offender’s special instinct, greed, etc. is revealed in murder. The variety of mercenary crime is contract killing. Self-interest is clearly expressed in it. Rarely, but it is possible contract killing and mercenary murder not to have any relation. If a killer got the order of murder and committed it with appropriate reward, the action should be qualified under the paragraph “G” of the Part 3 of the Article 109 of the Criminal Code, but order and self-interest should be indicated in the accusation. In this case, the qualification of a crime is not changed, but the double aggravating circumstances may be taken into account in the final sentence. As for an organizer of the murder, if he/she ordered killing without material compensation, depending on the specific situation, his/her action should be qualified as an organizer of contract killing or instigator of the murder. Keywords: Mercenary, mercenary crime, contract killing Introduction Mercenary is a human’s most negative quality, moral decomposition. -

Bias-Motivated Homicides: Toward a New Typology

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2018 Bias-Motivated Homicides: Toward a New Typology Lindsey Sank Davis The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2813 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] BIAS-MOTIVATED HOMICIDES: TOWARD A NEW TYPOLOGY by LINDSEY SANK DAVIS A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Psychology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2018 © 2018 LINDSEY SANK DAVIS All Rights Reserved ii Bias-Motivated Homicides: Toward a New Typology by Lindsey Sank Davis This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Psychology in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _________________ ________________________________________ Date Louis B. Schlesinger Chair of Examining Committee __________________ ________________________________________ Date Richard Bodnar Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Kevin L. Nadal Chitra Raghavan Sarah Craun Ernest Drucker THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Bias-Motivated Homicides: Toward a New Typology by Lindsey Sank Davis Advisor: Louis B. Schlesinger Despite significant progress towards equal protection under the law for women, LGBT individuals, and people of color in the United States, hate crime remains a pervasive problem, and rates appear to have increased in recent years. -

The Varieties of Homicide and Its Research

The Varieties of Homicide and Its Research Proceedings of the 1999 Meeting of the Homicide Research Working Group FBI Academy, Quantico, Virginia Editors Paul H. Blackman National Rifle Association Vanessa Levrier Leggett University of Houston-Downtown Brittawni Lee Olson National Research Corporation John P. Jarvis Federal Bureau of Investigation Findings and conclusions of the research reported here are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice or the Federal Bureau of Investigation. Published by FBI Academy, Federal Bureau of Investigation, U.S. Department of Justice. Cover design by Cynthis Laskiewicz, Behavioral Science Unit, FBI Academy. Suggested citation: Blackman, P.H., Leggett, V.L., Olson, B.L., & Jarvis, J.P. (Eds.). (2000). The varieties of homicide and its research: Proceedings of the 1999 meeting of the Homicide Research Working Group. Washington, DC: Federal Bureau of Investigation. FOREWORD Crime and violence continue to be a major challenge facing the nation. Encouragingly, recent statistics show marked declines in crime in the United States (Federal Bureau of Investigation, 1999). However, as recent as just a few years ago, rates for crimes of violence and homicide were recorded to be at near all time high levels. As a consequence, various efforts to respond to an apparent “epidemic of violence” in the United States resulted. Among these New York Cities’ COMPSTAT approach to crime analysis, Richmond, Virginia’s Project Exile to curb gun use, and the Boston Gun Project are but a few of the programmatic efforts that are widely believed to have contributed to the decline of violent crime rates within these communities. -

Proceedings of the 2004 Homicide Research Working Group Annual Symposium

LINKING DATA TO PRACTICE IN HOMICIDE AND VIOLENCE PREVENTION Proceedings of the 2004 Homicide Research Working Group Annual Symposium Edited by Valerie Pottie Bunge Carolyn Rebecca Block Michael Lane The Homicide Research Working Group (HRWG) is an international and interdisci- plinary organization of volunteers dedicated to cooperation among researchers and practi- tioners who are trying to understand and limit lethal violence. The HRWG has the following goals: ¾ to forge links between research, epidemiology and practical programs to reduce levels of mortality from violence; ¾ to promote improved data quality and the linking of diverse homicide data sources; ¾ to foster collaborative, interdisciplinary research on lethal and non-lethal violence; ¾ to encourage more efficient sharing of techniques for measuring and analyzing homicide; ¾ to create and maintain a communication network among those collecting, main- taining and analyzing homicide data sets; and ¾ to generate a stronger working relationship among homicide researchers. Homicide Research Working Group publications, which include the Proceedings of each annual Intensive Workshop (beginning in 1992), the HRWG Newsletter, and the contents of issues of the journal Homicide Studies (beginning in 1997), may be down- loaded from the HRWG web site, which is maintained by the Inter-University Consortium of Political and Social Research, at the following address: http://www.icpsr.umich.edu/HRWG/ Suggested citation: V. Pottie Bunge, C. R. Block and M. Lane (eds.) (2004). Linking Data to Practice in Violence and Homicide Prevention: Proceedings of the 2004 Meeting of the Homicide Research Working Group. Chicago, IL: HRWG Publications. The views expressed in these Proceedings are those of the authors and speakers, and not necessarily those of the Homicide Research Working Group or the editors of this volume.