National Register of Historic Places OCT 1 7 Multiple Property

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plans Call for Castleman Statue to Be Moved to Cave Hill Cemetery In

Volume XXVII Issue IV Page Volume XXVII Issue IV Winter 2018 www.cherokeetriangle.com Plans Call For Castleman Statue to be Moved to Cave Hill Cemetery in early 2019 By Leslie Millar President David Dowdell, Secretary Leslie Millar, Deputy Mayor Ellen Hesen reported that the city has Treasurer Amy Wells and Trustees Jennifer Schulz and been in a dialogue with Cave Hill Cemetery about plac- Clay Cockerham attended a meeting on Oct. 22, 2018 at ing the statue in the Castleman family plot. The city cur- the Mayor’s office in Louisville Metro Hall to discuss rently plans a long-term loan to the cemetery and expects the future of the Castleman statue and the roundabout that the relocation will likely take place in early 2019. site. Sarah Lindgren, Public Art Administrator, spoke about Mayor Fischer expressed a nuanced view of the monu- the process that the Committee on Public Art uses to ment in the aftermath of the 2017 riots in Charlottesville, evaluate proposals for commissions. Many models, in- Virginia. After an almost year-long public input process, cluding the rolling program of the Fourth Plinth in Tra- Mayor Fischer concluded that the statue would not be falgar Square (which displays unique sculpture from welcome in every part of the city. The Mayor ultimately around the world on a temporary display basis), exist that feels that the monument does not accurately reflect Lou- could provide fruitful paths for the Cherokee Triangle isville in its current cultural context. moving forward. Continued on page 7 CTA Fall Cocktail Party Helps Make The Triangle “a Little Village” Neighborhood Events By Peggie Elgin and Nick Morris Annual Judging to take Outdoor Holiday place the Party time in the Cherokee Trian- neighbors Decorating weekend. -

How Welfare Farms of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints Create Spiritual Communities

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Plan B and other Reports Graduate Studies 5-2012 Finding the Soul in the Soil: How Welfare Farms of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints Create Spiritual Communities Matthew L. Maughan Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/gradreports Recommended Citation Maughan, Matthew L., "Finding the Soul in the Soil: How Welfare Farms of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints Create Spiritual Communities" (2012). All Graduate Plan B and other Reports. 116. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/gradreports/116 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Plan B and other Reports by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Plan B and other Reports Graduate Studies 2012 Finding the Soul in the Soil: How Welfare Farms of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints Create Spiritual Communities Matthew L. Maughan Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.usu.edu/gradreports Recommended Citation Maughan, Matthew L., "Finding the Soul in the Soil: How Welfare Farms of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints Create Spiritual Communities" (2012). All Graduate Plan B and other Reports. Paper 116. This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Plan B and other Reports by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. -

Louisville Women and the Suffrage Movement 100 Years of the 19Th Amendment on the COVER: Kentucky Governor Edwin P

Louisville Women and the Suffrage Movement 100 Years of the 19th Amendment ON THE COVER: Kentucky Governor Edwin P. Morrow signing the 19th Amendment. Kentucky became the 23rd state to ratify the amendment. Library of Congress, Lot 5543 Credits: ©2020 Produced by Cave Hill Heritage Foundation in partnership with the Louisville Metro Office for Women, the League of Women Voters, Frazier History Museum, and Filson Historical Society Funding has been provided by Kentucky Humanities and the National Endowment for the Humanities. Any views, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this program do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities or Kentucky Humanities. Writing/Editing: Writing for You (Soni Castleberry, Gayle Collins, Eva Stimson) Contributing Writers and Researchers: Carol Mattingly, Professor Emerita, University of Louisville Ann Taylor Allen, Professor Emerita, University of Louisville Alexandra A. Luken, Executive Assistant, Cave Hill Heritage Foundation Colleen M. Dietz, Bellarmine University, Cave Hill Cemetery research intern Design/Layout: Anne Walker Studio Drawings: ©2020 Jeremy Miller Note about the artwork: The pen-and-ink drawings are based on photos which varied in quality. Included are portraits of all the women whose photos we were able to locate. Suff•rage, sŭf’•rĭj, noun: the right or privilege of voting; franchise; the exercise of such a right; a vote given in deciding a controverted question or electing a person for an office or trust The Long Road to Voting Rights for Women In the mid-1800s, women and men came together to advocate for women’s rights, with voting or suffrage rights leading the list. -

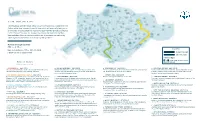

Ali's LOUISVILLE

ER RIV IO OH 7 65 71 1 11 MAIN MARKET JEFFE 264 RSON M UHAMM AD ALI 8 CH ESTNUT 5 64 B B ROAD A WAY X T 4 T E CAVE HILL LEXINGTON ROAD E R E T 3 A CEMETERY R E V T E E 2 S N R d U T n E S T 9 2 T E GR 2 h T AN t D E A E VE E NUE 5 E E E 1 R CHEROKEE V N L R A I T M R PTO K N T S O R T PARK C S T S D h t S O h d 7 t R E C n 4 J R 2 N N OAK P A A H M E L 10 O C S Y I A U W 65 RK E O A L B L P T A N AS R R C D TE Y S S N TO AUDUBON A N W E O N B R PARK O 6 P A R D E S T O KENTUCKY E N N A KINGDOM L 65 PS LI IL PH BELLARMINE UNIVERSITY 264 UNIVERSITY of LOUISVILLE ALI’S LOUISVILLE r i a L ali’S LOUISVILLE n visitor map h o when he spoke of home...he spoke of louisville. J : o t o h …tell ‘em I’m 1 Muhammad Ali Center* 7 Second Street Bridge P 2 Muhammad Ali Childhood Home 8 Muhammad Ali Boulevard from Louisville! 3 Columbia Gym 9 Smoketown Boxing 4 Cave Hill Cemetery Glove Monument I don’t want 5 Central High School 10 Kentucky Rushmore Chicago, or New 6 Freedom Hall 11 Ali’s Hometown Hero Banner “ * Denotes Fee for Admission York, or Texas to Ali’s hometown is home to other iconic attractions such as take the credit Churchill Downs – home of the Kentucky Derby® – and the Louisville Slugger Museum & Factory. -

Points of Interest Points of Interest (Lower Case Letters on the Map)

IF YOU LOSE YOUR WAY... The Broadway and Grinstead entrances are connected by a solid white line. Broken white lines intersect the solid lines which will eventually lead you to an entrance. A solid yellow line marks the road from the Grinstead entrance to Col. Harland Sanders’ lot. A green line marks the road from the Main Administration Office to Muhammad Ali’s lot. All sections are marked by cedar signs and are shown on the map by the symbol “•”. Monday through Saturday 8:00 pm - 4: 30 pm LEGEND Main Administration Office: 502-451-5630 Please call for an appointment ( ) broken line road ( ) solid line road • Section Signs a to z lower case letters indicate Points of Interest points of interest (lower case letters on the map) • MUHAMMAD ALI - SECTION U b WILDER MONUMENT - SECTION B h DOUGLASS LOT - SECTION G o CALDWELL SISTERS - SECTION 13 Humanitarian, Civil Rights Leader, Heavyweight Boxing Titleholder. Designed by Robert E. Launitz, “the father of monumental art in The family sold 49 acres to the Cemetery in 1863 with agreement that Family contributed money to build Sts. Mary & Elizabeth Hospital He championed peace and unity amongst the world. America”, and was erected in memory of Minnie, the Wilder’s only the fence around the family lot would remain. in 1872 in memory of their mother Mary Elizabeth Breckinridge child, who died at the age of seven. Caldwell. Sisters married European royalty. • SATTERWHITE MEMORIAL TEMPLE - SECTION C i TIFFANY VASE - SECTION N Preston Pope Satterwhite gave many antiques to the J.B. Speed Art c JAMES GUTHRIE - SECTION B Monument designed by Tiffany’s of New York. -

NOVEMBER 2019 (Continued from Previous Page) November Is Full of Historical Events for Us to Remember and Celebrate

15 11 number ISSUE 171 PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE TABLE OF CONTENTS October has been busy. We have President’s Message . 1 completed three of the five area Pioneer Stories . 3 trainings. Thanks to the AVP s for Membership Report . .. 4 making arrangements, providing National Calendar . 5 agendas, refreshments, and leading out 2020 Vision Trek . 6 in discussing local concerns. Thanks also Chapter News . 7 to all who have attended. The attendance Boulder Dam . 7 has been good even on the opening Box Elder . 8 weekend of the deer hunt. Centerville . 8 Cotton Mission . 9 The Pioneer Magazine issue featuring Eagle Rock . 9 articles on the transcontinental railroad; Jordan River Temple . 10 part of SUP’s celebration of the 150th Lehi . 10 anniversary of the driving of the golden Maple Mountain . 11 spike at Promontory Summit, is either in Morgan . 12 your hands or in the mail. Please enjoy. We are grateful to Bill Tanner, Mt Nebo . 12 the members of the Editorial Board and the authors for this fine issue. Porter Rockwell . 13 Portneuf . 14 Hopefully, all chapters have chosen new officers including Red Rocks . 14 presidents-elect so that chapter presidents and presidents-elect may Sevier . 14 attend the Presidents’ Christmas Dinner and Board meeting on Salt Lake Pioneer . 15 December 11 at the National Office Building. Invitations will come in Temple Quarry . .. 15 the mail with details. Timpanogos . .. 16 The July National Trek to Church history sites from Palmyra Upper Snake River Valley . 18 to Kirtland is fast filling. We are grateful to those who will be Brigham's Ball . -

Dialogue: a Journal of Mormon Thought Is Published Quarterly by the Dia- Logue Foundation

DIALOGUEa journal of mormon thought is an independent quarterly established to express Mormon culture and to examine the relevance of religion to secular life. It is edited by Latter-day Saints who wish to bring their faith into dialogue with the larger stream of world religious thought and with human experience as a whole and to foster artistic and scholarly achievement based on their cultural heritage. The journal encour- ages a variety of viewpoints; although every effort is made to ensure accurate scholarship and responsible judgment, the views express- ed are those of the individual authors and are not necessarily those of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints or of the editors. ii DIALOGUE: AJOURNAL OF MORMON THOUGHT, 46, no. 1 (SPRING 2014) Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought is published quarterly by the Dia- logue Foundation. Dialogue has no official connection with the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Contents copyright by the Dialogue Foundation. ISSN 0012–2157. Dialogue is available in full text in elec- tronic form at www.dialoguejournal.com and is archived by the Univer- sity of Utah Marriott Library Special Collections, available online at www.lib.utah.edu/portal/site/marriottlibrary. Dialogue is also available on microforms through University Microfilms International, www. umi.com, and online at dialoguejournal.com. Dialogue welcomes articles, essays, poetry, notes, fiction, letters to the editor, and art. Submissions should follow the current Chicago Manual of Style. All submissions should be in Word and may be submitted electroni- cally at https://dialoguejournal.com/submissions/. For submissions of visual art, please contact [email protected]. -

Irish Hill Neighborhood Plan 2002

IRISH HILL NEIGHBORHOOD PLAN FINAL OCTOBER 2002 - 1 - PDF processed with CutePDF evaluation edition www.CutePDF.com - 2 - Section I – Foreword - 3 - FOREWORD Irish Hill is perched on the east edge of downtown Louisville. Its location makes our neighborhood a key to achieving Mayor Armstrong’s plan of making Louisville a city in which to “live, work, and play.” Our neighborhood carries all these qualities: residences minutes from downtown, places of employment along the edge of downtown, and parks that anchor the ends of the neighborhood. Irish Hill carries potential for filling housing needs, preserving historical character, and being progressive in community building. However, in recent years many adverse land uses have diminished neighborhood quality of life and the character of the neighborhood’s residential fabric. The purpose of the Irish Hill Neighborhood Plan, therefore, is to: ° ensure correct and compatible land use and zoning ° to highlight and promote the neighborhood’s historical character ° to identify community needs ° to prepare a plan of action to secure the neighborhood’s future - 4 - Section II - Plan Process - 5 - PLAN PROCESS Work to develop this Irish Hill Neighborhood Plan commenced in January, 2002, following the appointment by Mayor David L. Armstrong of a neighborhood planning task force pursuant to City of Louisville ordinance No. 22, Series 19801. which guides the development of plans for City of Louisville neighborhoods. The Louisville Development Authority (LDA), the city’s principal community planning and development agency, was authorized by Mayor Armstrong to conduct the planning process. LDA, in turn, asked the Louisville Community Design Center (LCDC) to assist in plan development. -

Greater Jeffersontown Historical Society Newsletter

GREATER JEFFERSONTOWN HISTORICAL SOCIETY NEWSLETTER October 2016 Vol. 14 Number 5 October 2016 Meeting The October meeting will be held on Monday, October 3, 2016. We will meet at 7:00 P.M at the Jeffersontown Library, 10635 Watterson Trail. The Greater Jeffersontown Historical Society meetings are now held on the first Monday of the even numbered months of the year. Everyone is encouraged to attend to help guide and grow the Society. October Meeting – October 3 Catherine Bache will present a program on her Girl Scout Gold Award project, “Faces of Freedom: Preserving Underground Railroad Stories and Preventing Human Trafficking.” Underground Railroad myths and truths will be connected to myths and truths of modern day slavery, human trafficking. It is important to preserve the stories of the past so that we can better understand and address the issues that face us in the present. Locust Grove has requested that Catherine and her group present the play portion at Locust Grove on Friday, September 9. This will not be part of our program. The Girl Scout Gold Award is the equivalent to the Boy Scout Eagle Award. December Meeting We will have a luncheon at the Café on Main starting at 1:00 P.M. Possible Meeting Change – Day and Time Some members have requested we investigate changing our meeting time to the afternoon to accommodate those who have trouble coming to night meetings, especially in the winter months. I’ve talked with Deborah Anderson, Jeffersontown Branch librarian, and we would probably have to change days. It will depend on the renewals of groups that already regularly meet during the day. -

Points of Interest Points of Interest (Lower Case Letters on the Map)

IF YOU LOSE YOUR WAY... The Broadway and Grinstead entrances are connected by a solid white line. Broken white lines intersect the solid lines which will eventually lead you to an entrance. A solid yellow line marks the road from the Grinstead entrance to Col. Harland Sanders’ lot. A green line marks the road from the Main Administration Office to Muhammad Ali’s lot. All sections are marked by cedar signs and are shown on the map by the symbol “•”. Monday through Saturday 8:00 AM - 4: 30 PM LEGEND Main Administration Office: 502-451-5630 Please call for an appointment ( ) broken line road ( ) solid line road • Section Signs a to z lower case letters indicate Points of Interest points of interest (lower case letters on the map) • MUHAMMAD ALI - SECTION U b WILDER MONUMENT - SECTION B h DOUGLASS LOT - SECTION G o CALDWELL SISTERS - SECTION 13 Humanitarian, Civil Rights Leader, Heavyweight Boxing Titleholder. Designed by Robert E. Launitz, “the father of monumental art in The family sold 49 acres to the Cemetery in 1863 with agreement that Family contributed money to build Sts. Mary & Elizabeth Hospital He championed peace and unity amongst the world. America”, and was erected in memory of Minnie, the Wilder’s only the fence around the family lot would remain. in 1872 in memory of their mother Mary Elizabeth Breckinridge child, who died at the age of seven. Caldwell. Sisters married European royalty. • SATTERWHITE MEMORIAL TEMPLE - SECTION C i TIFFANY VASE - SECTION N Preston Pope Satterwhite gave many antiques to the J.B. Speed Art c JAMES GUTHRIE - SECTION B Monument designed by Tiffany’s of New York. -

March Is Women's History Month

THE TRAIL MARKER ~ OFFICIAL NEWSLETTER OF THE SOCIETY OF THE SONS OF UTAH PIONEERS 16 3 number ISSUE 175 PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE TABLE OF CONTENTS President’s Message . 1 Thanks to all who attended the Presidents’ National News . 3 Council meeting. Congratulations to chapters Membership Report . 3 which earned Chapter Recognition and National Calendar . 4 National Clean Up Day . 5 Chapter Excellence Awards. Strive to have National Historic Symposium . 6 your chapter qualify for an award in 2021. Pioneer Stories . 8 National Clean-up Day at Headquarters Monument Trek . 10 Chapter News . 12 is April 18th and an excellent National Boulder Dam . 12 Symposium is on April 25th. There are Box Elder . 13 registration forms and specific information Brigham Young . 13 regarding the Symposium in this Trail Cedar City . 14 Cotton Mission . 14 Marker. Remember the upcoming National Eagle Rock . 15 election. You may submit nominations Jordan River Temple . 15 beginning April 1 and running through April 30th for National President- Lehi . 16 elect. Maple Mountain . 17 Mills . 17 July 20th is the annual SUPer DUPer Day at This Is the Place State Park. Mt Nebo . 18 Tickets are half-price for SUP and DUP members and families. The park Morgan . 18 is open from 10:00 a. m. to 5:00 p.m. At 5:30 the Devotional begins with Mt Nebo . 19 President Dallin H. Oaks, First Councilor in the First Presidency as speaker. Murray . 20 Porter Rockwell . 21 July 24th will feature the Sunrise Devotional at the Assembly Hall on Portneuf . 21 Temple Square. Elder Allan F. -

LDS Perspectives Podcast

LDS Perspectives Podcast Episode 54: The JST in the D&C with Kenneth Alford (Released September 6, 2017) This is not a verbatim transcript. Some grammar and wording has been modified for clarity. Taunalyn: Hello, this is Taunalyn Rutherford, and I’m here today with Dr. Ken Alford to discuss his work on connections between the Doctrine and Covenants and the Joseph Smith Translation of the Bible. Welcome, Ken. Ken Alford: Great, thank you. I appreciate the invitation. Taunalyn: Great to have you. Dr. Ken Alford is a professor of church history and doctrine at Brigham Young University. He served a mission in Bristol, England. He earned a Bachelor of Arts degree in political science from Brigham Young University and a Master of Arts in international relations from the University of Southern California, a master of computer science from the University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign, and a PhD in computer science from George Mason University. After serving almost thirty years on active duty in the United States Army, he retired as a colonel in 2008. During his service, his assignments included work in the Pentagon, teaching at the United States Military Academy at West Point, and working as a professor and department chair at the National Defense University in Washington, D.C. He has published and presented on a wide variety of subjects during his career. His current research focuses on Latter-day Saint military service and the Hyrum Smith Papers project. Ken and his wife, Sherilee, have four children and fourteen grandchildren. Today we’ll be focusing on another of your research interests — the connections between the Joseph Smith Translation and the Doctrine and Covenants.