Undermining the Resource Super Profits Tax

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

14 June 2012 the Hon Tony Burke MP Minister for Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities Parliament House

14 June 2012 The Hon Tony Burke MP Minister for Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Dear Minister Burke On behalf of the Reference Group of Signatories under the Tasmanian Forests Intergovernmental Agreement, we are writing to provide a report on our progress to date and to formally request a short extension of time to enable us to conclude our negotiations. Over the last month the Signatories have been working intensively and in good spirit in an attempt to reach an agreement which optimises wood supply, conservation and community outcomes. Significant progress has been made but there are still a number of difficult issues to work through. The attached report, which is provided in accordance with Clause 45 of the Tasmanian Forests Intergovernmental Agreement, gives further detail on these issues. As set out in the report, the Signatories believe that a short extension until 23 July 2012 is both necessary and valuable to enable us to complete some additional analysis and finalise our negotiations. We have written in similar terms to the Tasmanian Deputy Premier, the Hon Bryan Green MP. Yours sincerely Don Henry Terry Edwards Chief Executive Officer Chief Executive Australian Conservation Foundation Forest Industries Association of Tasmania On behalf of the environmental organisation On behalf of the industry Signatories Signatories cc. Prime Minister, the Hon Julia Gillard MP Minister for Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry, Senator the Hon Joe Ludwig Minister for Regional Australia, Local Government and the Arts, the Hon Simon Crean MP Parliamentary Secretary for Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry, the Hon Sid Sidebottom MP . -

WEEKLY HANSARD Hansard Home Page: E-Mail: [email protected] Phone: (07) 3406 7314 Fax: (07) 3210 0182

PROOF ISSN 1322-0330 WEEKLY HANSARD Hansard Home Page: http://www.parliament.qld.gov.au/hansard/ E-mail: [email protected] Phone: (07) 3406 7314 Fax: (07) 3210 0182 51ST PARLIAMENT Subject CONTENTS Page Tuesday, 28 September 2004 ASSENT TO BILLS ........................................................................................................................................................................ 2349 OFFICE OF GOVERNOR ............................................................................................................................................................... 2349 FILMING OF PARLIAMENTARY PROCEEDINGS ........................................................................................................................ 2349 PHOTOGRAPHING IN CHAMBER ................................................................................................................................................ 2350 EMERGENCY EVACUATION DRILL ............................................................................................................................................. 2350 PETITIONS ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 2350 PAPERS ......................................................................................................................................................................................... 2350 MINISTERIAL STATEMENT ......................................................................................................................................................... -

The Foreign Minister Who Never Was

The foreign minister who never was BY:DENNIS SHANAHAN, POLITICAL EDITOR The Australian March 02, 2012 12:00AM Cartoon by Peter Nicholson. Source: The Australian JULIA Gillard's ability to turn good news - a brilliant political strategy, a poignant moment, or an opportunity to become strong, credible and assertive - into bad news and dumb politics appears to be boundless. And, when the Prime Minister has a brain snap, makes an error of judgment or gets into trouble for a reflexive and ill-considered denial the finger is pointed towards staff, speech writers, the hate media, Tony Abbott, or most of all, Kevin Rudd. The mistakes she's admitted are those where she neglected to publicly apportion blame to Rudd as a dysfunctional, pathological leader, and this being the reason for her taking over as prime minister in June 2010. On Monday morning, after three politically debilitating months of unforced errors, media disasters and a destabilising campaign to gather support for a Rudd leadership challenge, Gillard was finally in the clear. After a brilliant political strategy to force Rudd's hand early, at least two weeks before he was prepared to go, Gillard was able to crush him in the Labor caucus ballot 71 to 31 votes. Although there was a strong element of voting against Rudd rather than for Gillard in the ballot, it saw off Rudd's chances for this parliamentary term at least and gave Labor a chance to regather its thoughts and try to redeem a seemingly hopeless position. Gillard set out her intentions, addressing the public: "I can assure you that this political drama is over and now you are back at centre stage where you should properly be and you will be the focus of all of our efforts." On the issue of reshuffling her ministry and whether she would be punishing Rudd supporters, Gillard declared: "My focus will be on having a team based on merit and the ability to take the fight up on behalf of Labor to our conservative opponents. -

Legal and Constitutional Affairs References Committee

The Senate Legal and Constitutional Affairs References Committee Incident at the Manus Island Detention Centre from 16 February to 18 February 2014 December 2014 Commonwealth of Australia 2014 ISBN 978-1-76010-103-9 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License. The details of this licence are available on the Creative Commons website: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/au/. This document was produced by the Senate Legal and Constitutional Affairs Committee secretariat and printed by the Senate Printing Unit, Department of the Senate, Parliament House, Canberra. ii Members of the committee Members Senator Penny Wright (AG, SA) (Chair) Senator the Hon Ian Macdonald (LP, QLD) (Deputy Chair from 10.07.2014) Senator Catryna Bilyk (ALP, TAS) (from 01.07.2014) Senator Jacinta Collins (ALP, VIC) (from 01.07.2014) Senator the Hon Joe Ludwig (ALP, QLD) Senator Linda Reynolds (LP, WA) (from 01.07.2014) Former members Senator Zed Seselja (LP, ACT) (Deputy Chair until 30.06.2014) Senator Gavin Marshall (ALP, VIC) (until 30.06.2014) Senator the Hon Lisa Singh (ALP, TAS) (until 30.06.2014) Participating members Senator Sarah Hanson-Young (AG, SA) Secretariat Ms Sophie Dunstone, Committee Secretary Mr Matthew Corrigan, Principal Research Officer Ms Zoe Hutchinson, Principal Research Officer Mr CJ Sautelle, Acting Principal Research Officer Mr Jarrod Jolly, Senior Research Officer Mr Josh Wrest, Research Officer Ms Jo-Anne Holmes, Administrative Officer Suite S1.61 Telephone: (02) 6277 3560 Parliament House Fax: (02) 6277 5794 CANBERRA ACT 2600 Email: [email protected] iii iv Table of Contents Members of the committee .............................................................................. -

Shadow Ministry

Shadow Ministry 26 October 2004 - 28 January 2005 Leader of the Opposition Mark Latham Deputy Leader of the Opposition Shadow Minister for Education, Training, Science & Research Jenny Macklin, MP Leader of the Opposition in the Senate Shadow Minister for Social Security Senator Chris Evans Deputy Leader of the Opposition in the Senate Shadow Minister for Communications and Information Technology Senator Stephen Conroy Shadow Minister Health and Manager of Opposition Business in the House Julia Gillard, MP Shadow Treasurer Wayne Swan, MP Shadow Minister Industry, Infrastructure and Industrial Relations Stephen Smith, MP Shadow Minister Foreign Affairs and International Security Kevin Rudd, MP Shadow Minister Defence and Homeland Security Robert McClelland, MP Shadow Minister Trade The Hon Simon Crean, MP Shadow Minister for Primary Industries, Resources and Tourism Martin Ferguson, MP Shadow Minister for Environment and Heritage Deputy Manager of Opposition Business in the House Anthony Albanese, MP Shadow Minister for Public Administration and Open Government Shadow Minister for Indigenous Affairs and Reconciliation Shadow Minister for the Arts Senator Kim Carr Shadow Minister Regional Development and Roads, Housing and Urban Development Kelvin Thomson, MP Shadow Minister for Finance and Superannuation Senator Nick Sherry Shadow Minister for Work, Family and Community Shadow Minister for Youth and Early Childhood Education Shadow Minister Assisting the Leader on the Status of Women Tanya Plibersek, MP Shadow Minister Employment and Workplace -

24 September 2009 5:47Pm

Workplace Express - The source for IR/HR news. Page 1 of 3 Express Search TWG Delay for politicians' pay rise; Ex-CEO can't pursue claims in England; SDP Lacy off to Christmas & Cocos Islands; and more 24 September 2009 5:47pm Three month delay on politicians' 3% pay increase Former CEO can't serve claims in England: Federal Court SDP Lacy off to Christmas and Cocos Islands Full bench statement on award modernisation Three month delay on politicians' 3% pay increase The Remuneration Tribunal has awarded federal politicians a 3% wage increase but with a three- month lag before it is paid. It is their first rise since July 2007 after Prime Minister Kevin Rudd last year instigated a 12-month freeze. The increase is lower than the average 3.9% delivered in federal agreements for the June quarter this year (see see Related Article yesterday), but still comes at a time when the AFPC in its final decision before being abolished froze the rates of minimum wage earners. While the Tribunal usually makes its determinations effective from July 1, it has this year delayed the increase until October, reducing its value over the 12 months to 2.25%. The rise will take backbenchers' base salary to $131,040 from $127,060. Rudd will now earn $340,704, and Deputy Prime Minister Julia Gillard $268,632. Under the pay freeze Rudd put in place, there was no catch-up capacity. The parliamentary base salary is linked to the Remuneration Tribunal's executive office structure, and the increase applies to other public offices in its jurisdiction. -

An Examination of Australians of Hellenic Descent in the State Parliament of Victoria

LOUCA.qxd 15/1/2001 3:19 ìì Page 115 Louca, Procopis 2003. An Examination of Australians of Hellenic Descent in the State Parliament of Victoria. In E. Close, M. Tsianikas and G. Frazis (Eds.) “Greek Research in Australia: Proceedings of the Fourth Biennial Conference of Greek Studies, Flinders University, September 2001”. Flinders University Department of Languages – Modern Greek: Adelaide, 115-132. An Examination of Australians of Hellenic Descent in the State Parliament of Victoria Procopis Louca Victoria, the second most populated State in Australia, is widely claimed to include as its capital the third largest Grecophone city in the world, after Athens and Thessaloniki. The Victorian State Parliament has more members of Greek and Cypriot (Hellenic) background, than any other jurisdiction in the Commonwealth of Australia. Continuing a series of analyses of the role of elected State and Federal representatives of Hellenic descent in Australia (Louca, 2001), this paper will focus on the Victorian State Parliament, but with reference also to current and former Victorian Federal parliamentarians. There is an exploration of the cultural, political, social and personal influ- ences that guided these individuals to seek election to Parliament and their experiences as politicians with a Hellenic background. As at the beginning of 2002, six sitting members in the Victorian Parliament have a Hellenic background. Four represent the Australian Labor Party (ALP), two the Liberal Party. They are: Alex Andrianopoulos ALP Peter Katsambanis Liberal Nicholas Kotsiras Liberal Jenny Mikakos ALP John Pandazopoulos ALP Theo Theophanous ALP In addition to these current members, there are also two others who have re- tired from Parliament, or are deceased, Theo Sidiropoulos ALP (deceased) 115 Archived at Flinders University: dspace.flinders.edu.au LOUCA.qxd 15/1/2001 3:19 ìì Page 116 PROCOPIS LOUCA and Dimitri Dollis ALP (retired). -

National Police Service Medal

THE HISTORY OF THE ESTABLISHMENT OF THE NATIONAL POLICE SERVICE MEDAL 1 Almost since the Police Long Service and Good Conduct Medal was replaced by the National Medal in 1975 police associations and unions have been advocating the reintroduction of a police specific service award. At the 2006 Australasian Police Commissioners’ Conference, Commissioners received a submission and presentation from the Police Federation of Australia (PFA) regarding a proposal for a police-specific national medal to be awarded under the Australian Honours and Awards System. The underpinning argument of the PFA was that the awarding of a specific medal to sworn police officers would be a substantial acknowledgement of the unique role that sworn police officers play in the preservation of peace, the protection of life and property and the maintenance of law and order throughout Australia and overseas. The Commissioners’ Conference supported the PFA’s proposal and undertook to progress the award by setting up a Working Party with representatives from all jurisdictions, as well as the PFA. In the lead up to the 2007 Federal Election the PFA sought the following commitment from all political parties – “The PFA seeks your commitment to replacing the current National Medal with a new National Police Service Medal specifically for sworn members of Australia’s police forces.” The ALP won that election and incoming Prime Minister Kevin Rudd made the commitment that his government would support the proposal and enter into discussions with State and Territory Governments to seek an agreement. A submission was subsequently provided to the Prime Minister, which he endorsed. -

LETTER from CANBERRA TASMANIAN VIEWPOINT: GREG BARNS Saving You Time

7 June to 19 July 2011 LETTER FROM CANBERRA TASMANIAN VIEWPOINT: GREG BARNS Saving you time. Three years on. After Letter from Melbourne, established 1994. A monthly newsletter distilling public policy and government decisions which affect business opportunities in Australia and beyond. LETTER TheFROM Tasmanian Parliament’s CANBERRA upper house, the Legislative Council, is a unique beast in Australian politics. It is controlled by Independents and its electoral system and cycle Carbon Edition 7 June to 19 July 2011 Issue 35 Letter from Canberra is a monthly newsletterbears distilling no relationship public to thatpolicy of the and lower government house, LETTERthe House decisions FROMof Assembly. that CANBERRA effect business opportunities in Australia and beyond. You only need to be on a trip to miss out on the context of important stories. In a world of wall-to-wallThe information Legislative Council overload, is arguably we have Australia’s been onlysummarizing genuine house the of media review. and In classic Westminster constitutional theory, the upper house is not controlled by the executive and OUR MISSING GEOGRAPHY coffee-shop gossip for 18 years now, alongoperates with Letter to scrutinise from andMelbourne reviews bills.. This is the Tasmanian experience. !"#$%$#"&'()$*($+,-./01#,2)$'")(/1"3$ '/(,-!!"#4)/1 LESSONS... Letter)56789:6;$6;<=9;$>?$/8@=6;9$%A?A$BCD$E=$:C@=$@F;$D9BG$@=$G:C$%$C:EF@7H$:C8I5D:CE$69;BJ<B7@$<=9$@G=H$B@$(F;$'=@;I$!:CD7=9K from Canberra is focused on the interfaceThe Legislative of business Council and consists government, of 15 MPs. with They enoughrepresent politics single member and policy background to enable you to grasp anyconstituencies. -

Additional Estimates 2010-11 (February 2011)

Senate Finance and Public Administration Legislation Committee ANSWERS TO QUESTIONS ON NOTICE ADDITIONAL ESTIMATES 2010-2011 Prime Minister and Cabinet Portfolio Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet Question: PM23 Topic: Government Staffing Committee/Code of Conduct for Ministerial Staff Asked By: Senator Ryan Type of Question: Written Date set by the committee for the return of answer: 15 April 2011 Number of pages: 2 1. Who are the members of the Government Staffing Committee? 2. Does it have specific guidelines or remit? 3. Is there a Government Staffing Committee Secretariat? 4. Have any Ministerial Staff or electorate officers been sanctioned under the Code of Conduct for Ministerial Staff? 5. How many times has the government staffing committee met? If so when did they meet? Answer: 1. The members of the Government Staffing Committee are: a. the Deputy Prime Minister, the Hon Wayne Swan MP b. the Special Minister of State, the Hon Gary Gray MP c. the Minister for Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry (and the previous Special Minister of State) Senator the Hon Joe Ludwig, and d. the Prime Minister’s Chief of Staff, Mr Ben Hubbard (previously Ms Amanda Lampe). 2. The Committee makes recommendations to the Prime Minister on staffing matters requiring her decision and approves senior ministerial staff appointments. Senate Finance and Public Administration Legislation Committee ANSWERS TO QUESTIONS ON NOTICE ADDITIONAL ESTIMATES 2010-2011 Prime Minister and Cabinet Portfolio Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet 3. The Governance and Administration Unit in the Prime Minister’s Office provides the secretariat services for the Committee. -

Ministerial Departures 1901-2017

RESEARCH PAPER SERIES, 2017–18 12 JULY 2017 That’s it—I’m leaving: ministerial departures 1901–2017 Janet Wilson and Margaret Healy Politics and Public Administration Section Contents Abbreviations .............................................................................................. 3 Introduction ................................................................................................ 4 Ministerial responsibility ............................................................................. 5 Barton Ministry (Protectionist) 1.1.1901 – 24.9.1903 .................................... 8 2nd Deakin Ministry (Protectionist) 5.7.1905 – 13.11.1908 ............................ 8 3rd Fisher Ministry (ALP) 17.9.1914 – 27.10.1915 .......................................... 9 1st Hughes Ministry (ALP) 27.10.1915 – 14.11.1916 ...................................... 9 3rd Hughes Ministry (Nationalist) 17.2.1917 – 10.1.1918 ............................. 10 4th Hughes Ministry (Nationalist) 10.1.1918 – 9.2.1923 ............................... 10 Bruce–Page Ministry (Nationalist–CP Coalition) 9.2.1923 – 22.10.1929 ......... 12 Scullin Ministry (ALP) 22.10.1929 – 6.1.1932 ................................................ 12 1st Lyons Ministry (UAP) 6.1.1932 – 9.11.1934; (UAP–CP Coalition) 9.11.1934 – 7.11.1938 ................................................................................. 13 2nd Lyons Ministry (UAP–CP Coalition) 7.11.1938 – 7.4.1939 ....................... 15 Page Ministry (CP–UAP Coalition) 7.4.1939 – 26.4.1939 .............................. -

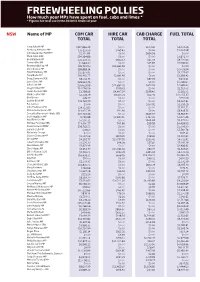

Freewheeling Pollies How Much Your Mps Have Spent on Fuel, Cabs and Limos * * Figures for Total Use in the 2010/11 Financial Year

FREEWHEELING POLLIES How much your MPs have spent on fuel, cabs and limos * * Figures for total use in the 2010/11 financial year NSW Name of MP COM CAR HIRE CAR CAB CHARGE FUEL TOTAL TOTAL TOTAL TOTAL Tony Abbott MP $217,866.39 $0.00 $103.42 $4,559.36 Anthony Albanese MP $35,123.59 $265.43 $0.00 $1,394.98 John Alexander OAM MP $2,110.84 $0.00 $694.56 $0.00 Mark Arbib SEN $34,164.86 $0.00 $0.00 $2,806.77 Bob Baldwin MP $23,132.73 $942.53 $65.59 $9,731.63 Sharon Bird MP $1,964.30 $0.00 $25.83 $3,596.90 Bronwyn Bishop MP $26,723.90 $33,665.56 $0.00 $0.00 Chris Bowen MP $38,883.14 $0.00 $0.00 $2,059.94 David Bradbury MP $15,877.95 $0.00 $0.00 $4,275.67 Tony Burke MP $40,360.77 $2,691.97 $0.00 $2,358.42 Doug Cameron SEN $8,014.75 $0.00 $87.29 $404.41 Jason Clare MP $28,324.76 $0.00 $0.00 $1,298.60 John Cobb MP $26,629.98 $11,887.29 $674.93 $4,682.20 Greg Combet MP $14,596.56 $749.41 $0.00 $1,519.02 Helen Coonan SEN $1,798.96 $4,407.54 $199.40 $1,182.71 Mark Coulton MP $2,358.79 $8,175.71 $62.06 $12,255.37 Bob Debus $49.77 $0.00 $0.00 $550.09 Justine Elliot MP $21,762.79 $0.00 $0.00 $4,207.81 Pat Farmer $0.00 $0.00 $177.91 $1,258.29 John Faulkner SEN $14,717.83 $0.00 $0.00 $2,350.51 Mr Laurie Ferguson MP $14,055.39 $90.91 $0.00 $3,419.75 Concetta Fierravanti-Wells SEN $20,722.46 $0.00 $649.97 $3,912.97 Joel Fitzgibbon MP 9,792.88 $7,847.45 $367.41 $2,675.46 Paul Fletcher MP $7,590.31 $0.00 $464.68 $2,475.50 Michael Forshaw SEN $13,490.77 $95.86 $98.99 $4,428.99 Peter Garrett AM MP $39,762.55 $0.00 $0.00 $1,009.30 Joanna Gash MP $78.60 $0.00