Ministerial Speech

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

14 June 2012 the Hon Tony Burke MP Minister for Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities Parliament House

14 June 2012 The Hon Tony Burke MP Minister for Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Dear Minister Burke On behalf of the Reference Group of Signatories under the Tasmanian Forests Intergovernmental Agreement, we are writing to provide a report on our progress to date and to formally request a short extension of time to enable us to conclude our negotiations. Over the last month the Signatories have been working intensively and in good spirit in an attempt to reach an agreement which optimises wood supply, conservation and community outcomes. Significant progress has been made but there are still a number of difficult issues to work through. The attached report, which is provided in accordance with Clause 45 of the Tasmanian Forests Intergovernmental Agreement, gives further detail on these issues. As set out in the report, the Signatories believe that a short extension until 23 July 2012 is both necessary and valuable to enable us to complete some additional analysis and finalise our negotiations. We have written in similar terms to the Tasmanian Deputy Premier, the Hon Bryan Green MP. Yours sincerely Don Henry Terry Edwards Chief Executive Officer Chief Executive Australian Conservation Foundation Forest Industries Association of Tasmania On behalf of the environmental organisation On behalf of the industry Signatories Signatories cc. Prime Minister, the Hon Julia Gillard MP Minister for Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry, Senator the Hon Joe Ludwig Minister for Regional Australia, Local Government and the Arts, the Hon Simon Crean MP Parliamentary Secretary for Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry, the Hon Sid Sidebottom MP . -

Legal and Constitutional Affairs References Committee

The Senate Legal and Constitutional Affairs References Committee Incident at the Manus Island Detention Centre from 16 February to 18 February 2014 December 2014 Commonwealth of Australia 2014 ISBN 978-1-76010-103-9 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License. The details of this licence are available on the Creative Commons website: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/au/. This document was produced by the Senate Legal and Constitutional Affairs Committee secretariat and printed by the Senate Printing Unit, Department of the Senate, Parliament House, Canberra. ii Members of the committee Members Senator Penny Wright (AG, SA) (Chair) Senator the Hon Ian Macdonald (LP, QLD) (Deputy Chair from 10.07.2014) Senator Catryna Bilyk (ALP, TAS) (from 01.07.2014) Senator Jacinta Collins (ALP, VIC) (from 01.07.2014) Senator the Hon Joe Ludwig (ALP, QLD) Senator Linda Reynolds (LP, WA) (from 01.07.2014) Former members Senator Zed Seselja (LP, ACT) (Deputy Chair until 30.06.2014) Senator Gavin Marshall (ALP, VIC) (until 30.06.2014) Senator the Hon Lisa Singh (ALP, TAS) (until 30.06.2014) Participating members Senator Sarah Hanson-Young (AG, SA) Secretariat Ms Sophie Dunstone, Committee Secretary Mr Matthew Corrigan, Principal Research Officer Ms Zoe Hutchinson, Principal Research Officer Mr CJ Sautelle, Acting Principal Research Officer Mr Jarrod Jolly, Senior Research Officer Mr Josh Wrest, Research Officer Ms Jo-Anne Holmes, Administrative Officer Suite S1.61 Telephone: (02) 6277 3560 Parliament House Fax: (02) 6277 5794 CANBERRA ACT 2600 Email: [email protected] iii iv Table of Contents Members of the committee .............................................................................. -

24 September 2009 5:47Pm

Workplace Express - The source for IR/HR news. Page 1 of 3 Express Search TWG Delay for politicians' pay rise; Ex-CEO can't pursue claims in England; SDP Lacy off to Christmas & Cocos Islands; and more 24 September 2009 5:47pm Three month delay on politicians' 3% pay increase Former CEO can't serve claims in England: Federal Court SDP Lacy off to Christmas and Cocos Islands Full bench statement on award modernisation Three month delay on politicians' 3% pay increase The Remuneration Tribunal has awarded federal politicians a 3% wage increase but with a three- month lag before it is paid. It is their first rise since July 2007 after Prime Minister Kevin Rudd last year instigated a 12-month freeze. The increase is lower than the average 3.9% delivered in federal agreements for the June quarter this year (see see Related Article yesterday), but still comes at a time when the AFPC in its final decision before being abolished froze the rates of minimum wage earners. While the Tribunal usually makes its determinations effective from July 1, it has this year delayed the increase until October, reducing its value over the 12 months to 2.25%. The rise will take backbenchers' base salary to $131,040 from $127,060. Rudd will now earn $340,704, and Deputy Prime Minister Julia Gillard $268,632. Under the pay freeze Rudd put in place, there was no catch-up capacity. The parliamentary base salary is linked to the Remuneration Tribunal's executive office structure, and the increase applies to other public offices in its jurisdiction. -

National Police Service Medal

THE HISTORY OF THE ESTABLISHMENT OF THE NATIONAL POLICE SERVICE MEDAL 1 Almost since the Police Long Service and Good Conduct Medal was replaced by the National Medal in 1975 police associations and unions have been advocating the reintroduction of a police specific service award. At the 2006 Australasian Police Commissioners’ Conference, Commissioners received a submission and presentation from the Police Federation of Australia (PFA) regarding a proposal for a police-specific national medal to be awarded under the Australian Honours and Awards System. The underpinning argument of the PFA was that the awarding of a specific medal to sworn police officers would be a substantial acknowledgement of the unique role that sworn police officers play in the preservation of peace, the protection of life and property and the maintenance of law and order throughout Australia and overseas. The Commissioners’ Conference supported the PFA’s proposal and undertook to progress the award by setting up a Working Party with representatives from all jurisdictions, as well as the PFA. In the lead up to the 2007 Federal Election the PFA sought the following commitment from all political parties – “The PFA seeks your commitment to replacing the current National Medal with a new National Police Service Medal specifically for sworn members of Australia’s police forces.” The ALP won that election and incoming Prime Minister Kevin Rudd made the commitment that his government would support the proposal and enter into discussions with State and Territory Governments to seek an agreement. A submission was subsequently provided to the Prime Minister, which he endorsed. -

LETTER from CANBERRA TASMANIAN VIEWPOINT: GREG BARNS Saving You Time

7 June to 19 July 2011 LETTER FROM CANBERRA TASMANIAN VIEWPOINT: GREG BARNS Saving you time. Three years on. After Letter from Melbourne, established 1994. A monthly newsletter distilling public policy and government decisions which affect business opportunities in Australia and beyond. LETTER TheFROM Tasmanian Parliament’s CANBERRA upper house, the Legislative Council, is a unique beast in Australian politics. It is controlled by Independents and its electoral system and cycle Carbon Edition 7 June to 19 July 2011 Issue 35 Letter from Canberra is a monthly newsletterbears distilling no relationship public to thatpolicy of the and lower government house, LETTERthe House decisions FROMof Assembly. that CANBERRA effect business opportunities in Australia and beyond. You only need to be on a trip to miss out on the context of important stories. In a world of wall-to-wallThe information Legislative Council overload, is arguably we have Australia’s been onlysummarizing genuine house the of media review. and In classic Westminster constitutional theory, the upper house is not controlled by the executive and OUR MISSING GEOGRAPHY coffee-shop gossip for 18 years now, alongoperates with Letter to scrutinise from andMelbourne reviews bills.. This is the Tasmanian experience. !"#$%$#"&'()$*($+,-./01#,2)$'")(/1"3$ '/(,-!!"#4)/1 LESSONS... Letter)56789:6;$6;<=9;$>?$/8@=6;9$%A?A$BCD$E=$:C@=$@F;$D9BG$@=$G:C$%$C:EF@7H$:C8I5D:CE$69;BJ<B7@$<=9$@G=H$B@$(F;$'=@;I$!:CD7=9K from Canberra is focused on the interfaceThe Legislative of business Council and consists government, of 15 MPs. with They enoughrepresent politics single member and policy background to enable you to grasp anyconstituencies. -

Additional Estimates 2010-11 (February 2011)

Senate Finance and Public Administration Legislation Committee ANSWERS TO QUESTIONS ON NOTICE ADDITIONAL ESTIMATES 2010-2011 Prime Minister and Cabinet Portfolio Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet Question: PM23 Topic: Government Staffing Committee/Code of Conduct for Ministerial Staff Asked By: Senator Ryan Type of Question: Written Date set by the committee for the return of answer: 15 April 2011 Number of pages: 2 1. Who are the members of the Government Staffing Committee? 2. Does it have specific guidelines or remit? 3. Is there a Government Staffing Committee Secretariat? 4. Have any Ministerial Staff or electorate officers been sanctioned under the Code of Conduct for Ministerial Staff? 5. How many times has the government staffing committee met? If so when did they meet? Answer: 1. The members of the Government Staffing Committee are: a. the Deputy Prime Minister, the Hon Wayne Swan MP b. the Special Minister of State, the Hon Gary Gray MP c. the Minister for Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry (and the previous Special Minister of State) Senator the Hon Joe Ludwig, and d. the Prime Minister’s Chief of Staff, Mr Ben Hubbard (previously Ms Amanda Lampe). 2. The Committee makes recommendations to the Prime Minister on staffing matters requiring her decision and approves senior ministerial staff appointments. Senate Finance and Public Administration Legislation Committee ANSWERS TO QUESTIONS ON NOTICE ADDITIONAL ESTIMATES 2010-2011 Prime Minister and Cabinet Portfolio Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet 3. The Governance and Administration Unit in the Prime Minister’s Office provides the secretariat services for the Committee. -

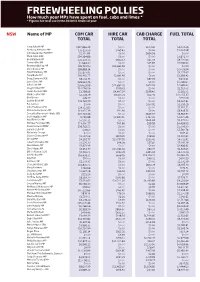

Freewheeling Pollies How Much Your Mps Have Spent on Fuel, Cabs and Limos * * Figures for Total Use in the 2010/11 Financial Year

FREEWHEELING POLLIES How much your MPs have spent on fuel, cabs and limos * * Figures for total use in the 2010/11 financial year NSW Name of MP COM CAR HIRE CAR CAB CHARGE FUEL TOTAL TOTAL TOTAL TOTAL Tony Abbott MP $217,866.39 $0.00 $103.42 $4,559.36 Anthony Albanese MP $35,123.59 $265.43 $0.00 $1,394.98 John Alexander OAM MP $2,110.84 $0.00 $694.56 $0.00 Mark Arbib SEN $34,164.86 $0.00 $0.00 $2,806.77 Bob Baldwin MP $23,132.73 $942.53 $65.59 $9,731.63 Sharon Bird MP $1,964.30 $0.00 $25.83 $3,596.90 Bronwyn Bishop MP $26,723.90 $33,665.56 $0.00 $0.00 Chris Bowen MP $38,883.14 $0.00 $0.00 $2,059.94 David Bradbury MP $15,877.95 $0.00 $0.00 $4,275.67 Tony Burke MP $40,360.77 $2,691.97 $0.00 $2,358.42 Doug Cameron SEN $8,014.75 $0.00 $87.29 $404.41 Jason Clare MP $28,324.76 $0.00 $0.00 $1,298.60 John Cobb MP $26,629.98 $11,887.29 $674.93 $4,682.20 Greg Combet MP $14,596.56 $749.41 $0.00 $1,519.02 Helen Coonan SEN $1,798.96 $4,407.54 $199.40 $1,182.71 Mark Coulton MP $2,358.79 $8,175.71 $62.06 $12,255.37 Bob Debus $49.77 $0.00 $0.00 $550.09 Justine Elliot MP $21,762.79 $0.00 $0.00 $4,207.81 Pat Farmer $0.00 $0.00 $177.91 $1,258.29 John Faulkner SEN $14,717.83 $0.00 $0.00 $2,350.51 Mr Laurie Ferguson MP $14,055.39 $90.91 $0.00 $3,419.75 Concetta Fierravanti-Wells SEN $20,722.46 $0.00 $649.97 $3,912.97 Joel Fitzgibbon MP 9,792.88 $7,847.45 $367.41 $2,675.46 Paul Fletcher MP $7,590.31 $0.00 $464.68 $2,475.50 Michael Forshaw SEN $13,490.77 $95.86 $98.99 $4,428.99 Peter Garrett AM MP $39,762.55 $0.00 $0.00 $1,009.30 Joanna Gash MP $78.60 $0.00 -

Ministry List

Commonwealth Government SECOND GILLARD MINISTRY 14 December 2011 TITLE MINISTER Prime Minister The Hon Julia Gillard MP Minister Assisting the Prime Minister on Digital Productivity Senator the Hon Stephen Conroy Minister for Social Inclusion The Hon Mark Butler MP Minister Assisting the Prime Minister on Mental Health Reform The Hon Mark Butler MP Minister for the Public Service and Integrity The Hon Gary Gray AO MP Minister Assisting the Prime Minister on the Centenary of ANZAC The Hon Warren Snowdon MP Cabinet Secretary The Hon Mark Dreyfus QC MP Parliamentary Secretary to the Prime Minister Senator the Hon Kate Lundy Treasurer The Hon Wayne Swan MP (Deputy Prime Minister) Minister for Financial Services and Superannuation The Hon Bill Shorten MP Assistant Treasurer Senator the Hon Mark Arbib (Manager of Government Business in the Senate) Parliamentary Secretary to the Treasurer The Hon David Bradbury MP Minister for Tertiary Education, Skills, Science and Research Senator the Hon Chris Evans (Leader of the Government in the Senate) Minister for Industry and Innovation The Hon Greg Combet AM MP Minister for Manufacturing Senator the Hon Kim Carr Minister for Small Business Senator the Hon Mark Arbib Parliamentary Secretary for Industry and Innovation The Hon Mark Dreyfus QC MP Minister for Broadband, Communications and the Digital Economy Senator the Hon Stephen Conroy (Deputy Leader of the Government in the Senate) Minister for Regional Australia, Regional Development and Local Government The Hon Simon Crean MP Minister for the Arts -

The Whistleno. 60, October 2009

“All that is needed for evil to prosper is for people of good will to do nothing”—Edmund Burke The Whistle No. 60, October 2009 Newsletter of Whistleblowers Australia Allan Kessing: read comments on his saga, pages 7–11 and 16 Media watch Let’s protect the brave Sherron Watkins, the corporate vice- The Senate committee hearing president who revealed accounting involving Godwin Grech raises ones who speak out fraud at Enron, and Toni Hoffman, important questions: whether Grech Godwin Grech’s plight puts a new who disclosed life-threatening prac- was influenced to appear; the veracity spin on “without fear or favour.” tices at the Bundaberg Hospital, are of his testimony; and whether the Kim Sawyer examples. presence of a supervisor and the The Age (Melbourne), 29 June 2009 Most whistleblowers, however, are disagreement among senators inter- not unequivocally vindicated. They fered with his testimony. THE case of Godwin Grech has often struggle for years to shore up We expect witnesses to be truthful, important implications for public their credibility and, by implication, and we also expect them to be interest disclosures in Australia. It has the credibility of their whistleblowing. protected. brought into focus whether a possible The Grech case shows how quickly the Witnesses to senate inquiries, like whistleblower was indeed a whistle- situation for a possible whistleblower whistleblowers, are on their own. blower. It has turned a government can invert. There is no room for error, They are given protections codified with a commitment to public interest and certainly no room for fraud. by parliamentary privilege, including disclosures into a government pursuing There may be uncertainty about the protection against legal action, the public service leakers. -

Opening Address Joe Ludwig Paper Prepared for Presentation at The

Opening Address Joe Ludwig Paper prepared for presentation at the “The Supermarket Revolution In Food: Good, bad or ugly for the world’s farmers, consumers and retailers?” conference conducted by the Crawford Fund for International Agricultural Research, Parliament House, Canberra, Australia, 14-16 August 2011 Copyright 2011 by Joe Ludwig. All rights reserved. Readers may make verbatim copies of this document for non-commercial purposes by any means, provided that this copyright notice appears on all such copies. Opening Address* Senator the Hon. Joe Ludwig Minister for Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry The Crawford Fund’s work in promoting and supporting international agricultural research, begun in 1987, becomes more relevant with each passing year. I congratulate the Fund on its commitment to supporting developing countries, tackling food security and alleviating rural poverty. Challenges and discussions This conference agenda covers plenty of ground in what is a very wide debate that impacts right across our community. Food and supermarkets are a universal issue. As this conference clearly is designed to discuss, we should not underestimate the impact that the supermarket revolution has had on the production, supply and management of food — and also on the understanding of food. The divide, or the gap, between the farm gate and the consumer is larger than ever, and it sits at odds with modern consumer trends. Consumers can purchase a wider range of products than ever before and are aware of foods, flavours and meals that were unheard of a generation ago. Yet the typical consumer now has much smaller knowledge of, and is much further from, the farm gate and food processor than were earlier generations. -

October 2010 Newsletter

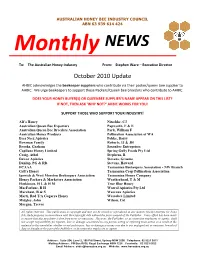

AUSTRALIAN HONEY BEE INDUSTRY COUNCIL ABN 63 939 614 424 NEWS Monthly To: The Australian Honey Industry From:D StephenS Ware – Executive Director October 2010 Update AHBIC acknowledges the beekeeper suppliers who contribute via their packer/queen bee supplier to AHBIC. We urge beekeepers to support those Packers/Queen bee breeders who contribute to AHBIC. DOES YOUR HONEY BUYER(S) OR QUEENBEE SUPPLIER’S NAME APPEAR ON THIS LIST? IF NOT, THEN ASK ‘WHY NOT?’ AHBIC WORKS FOR YOU! SUPPORT THOSE WHO SUPPORT YOUR INDUSTRY! AB’s Honey Nitschke, CJ Australian Queen Bee Exporters Papworth, F & E Australian Queen Bee Breeders Association Park, William F Australian Honey Products Pollination Association of WA Bees Neez Apiaries Pobke, Barry Bowman Family Roberts, IJ & JH Brooks, Graham Saxonbee Enterprises Capilano Honey Limited Spring Gully Foods Pty Ltd Craig, Athol Stephens, R Dewar Apiaries Stevens, Graeme Dunlop, PG & RD Stevens, Howard FCAAA Tasmanian Beekeepers Association - NW Branch Gell’s Honey Tasmanian Crop Pollination Association Ipswich & West Moreton Beekeepers Association Tasmanian Honey Company Honey Packers & Marketers Association Weatherhead, T & M Hoskinson, H L & H M True Blue Honey MacFarlane, R H Warral Apiaries Pty Ltd Marchant, R & S Weerona Apiaries Marti, Rod T/A Gagarra Honey Wescobee Limited Midgley, John Wilson, Col Morgan, Trevor All rights reserved. This publication is copyright and may not be resold or reproduced in any manner (except excerpts for bona fide study purposes in accordance with the Copyright Act) without the prior consent of the Publisher. Every effort has been made to ensure that this newsletter is free from error or omissions. -

The Gillard Government's New Ministry - an Overview of Government Priorities

The Gillard government's new Ministry - An overview of government priorities Parliamentary Total Cabinet Minister Cabinet Portfolio Outer Minister Outer Ministry Portfolio Topic area secretary People Julia Gillard MP • Prime Minister 1 2 Wayne Swan MP • Deputy Prime Minister Bill Shorten MP • Assistant Treasurer 2 4 Economics • Treasurer • Minister for Financial Services and Superannuation Kevin Rudd MP • Minister for Foreign Affairs 1 2 Diplomacy Senator Chris Evans • Minister for Tertiary Education, Jobs, Skills and Workplace Tanya Plibersek MP • Minister for Human Services 0.5 2.5 Social Inclusion / Jobs Relations • Minister for Social Inclusion Kate Ellis MP • Minister for the Status of Women 0.5 Jobs • Minister for Employment Participation and Childcare Senator Mark Arbib • Minister for Indigenous Employment and Economic 0.5 Indigenous jobs Development Simon Crean MP • Minister for Regional Australia, Regional Development and All Cabinet Ministers Economic services Local Government • Minister for the Arts Stephen Smith MP • Minister for Defence Warren Snowdon MP • Minister for Veterans' Affairs .5 +1 3.5 Defence • Minister for Defence Science and Personnel Jason Clare MP • Minister for Defence Materiel Nicola Roxon MP • Minister for Health and Ageing Mark Butler MP • Minister for Mental Health and Ageing 0.5 3 Human services Warren Snowdon MP • Minister for Indigenous Health 0.5 Jenny Macklin MP • Minister for FaHCSIA Senator Mark Arbib • Minister for Sport .25 + 2 3.25 Human services • Minister for Social Housing and Homelessness