Faces of a Sðd+U

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Great Mahayogi Devraha Baba's Biography-His Divine Sports and Lilas

SHRI DEVRAHA BABA LILA DARSHAN GREAT MAHAYOGI DEVRAHA BABA’S BIOGRAPHY-HIS DIVINE SPORTS AND LILAS ORIGINALLY WRITTEN IN HINDI BY COMPILED AND PUBLISHED ON THE INTERNET BY TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH BY MS/ HEENA A. KAPADIA (M.Sc., M.Phil) 1/168 SHRI DEVRAHA BABA LILA DARSHAN INDEX INDIA’S FUTURE SEER SAINT SHRI DEVRAHA BABA SARKAR ........................................................................ 7 BHAKTI BHAKT BHAGWANT GURU CHATURNAM VAPU EK ....................................................................... 10 INKE PADA VANDAN KIYE NASAI VIGHAN ANEK ......................................................................................... 10 CHAPTER 1 .................................................................................................................................................. 20 AN EPISODE RELATED TO INDIA’S FIRST PRESIDENT-DR RAJENDRA PRASAD ............................................ 20 CHAPTER 2 .................................................................................................................................................. 22 SPIRITUAL MESSAGE GIVEN BY HH MAHAYOGI DEVRAHA BABA TO INDIA’S FIRST MUSLIM PRESIDENT . 22 CHAPTER 3 .................................................................................................................................................. 25 THE OMNISCIENT MAYAYOGI HH DEVRAHA BABA AND A BRITISH SPY ..................................................... 25 CHAPTER 4 ................................................................................................................................................. -

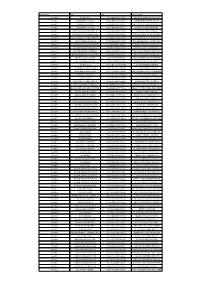

Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name 01600009 GHOSH JAYA

Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name 01600009 GHOSH JAYA U72200WB2005PTC104166 ANI INFOGEN PRIVATE LIMITED 01600031 KISHORE RAJ YADAV U24230BR1991PTC004567 RENHART HEALTH PRODUCTS 01600031 KISHORE RAJ YADAV U00800BR1996PTC007074 ZINNA CAPITAL & SAVING PRIVATE 01600031 KISHORE RAJ YADAV U00365BR1996PTC007166 RAWATI COMMUNICATIONS 01600058 ARORA KEWAL KUMAR RITESH U80301MH2008PTC188483 YUKTI TUTORIALS PRIVATE 01600063 KARAMSHI NATVARLAL PATEL U24299GJ1966PTC001427 GUJARAT PHENOLIC SYNTHETICS 01600094 BUTY PRAFULLA SHREEKRISHNA U91110MH1951NPL010250 MAHARAJ BAG CLUB LIMITED 01600095 MANJU MEHTA PRAKASH U72900MH2000PTC129585 POLYESTER INDIA.COM PRIVATE 01600118 CHANDRASHEKAR SOMASHEKAR U55100KA2007PTC044687 COORG HOSPITALITIES PRIVATE 01600119 JAIN NIRMALKUMAR RIKHRAJ U00269PN2006PTC022256 MAHALAXMI TEX-CLOTHING 01600119 JAIN NIRMALKUMAR RIKHRAJ U29299PN2007PTC130995 INNOVATIVE PRECITECH PRIVATE 01600126 DEEPCHAND MEHTA VALCHAND U52393MH2007PTC169677 DEEPSONS JEWELLERS PRIVATE 01600133 KESARA MANILAL PATEL U24299GJ1966PTC001427 GUJARAT PHENOLIC SYNTHETICS 01600141 JAIN REKHRAJ SHIVRAJ U00269PN2006PTC022256 MAHALAXMI TEX-CLOTHING 01600144 SUNITA TULI U65993DL1991PLC042580 TULI INVESTMENT LIMITED 01600152 KHANNA KUMAR SHYAM U65993DL1991PLC042580 TULI INVESTMENT LIMITED 01600158 MOHAMED AFZAL FAYAZ U51494TN2005PTC056219 FIDA FILAMENTS PRIVATE LIMITED 01600160 CHANDER RAMESH TULI U65993DL1991PLC042580 TULI INVESTMENT LIMITED 01600169 JUNEJA KAMIA U32109DL1999PTC099997 JUNEJA SALES PRIVATE LIMITED 01600182 NARAYANLAL SARDA SHARAD U00269PN2006PTC022256 -

Super Power Yajna Is Our Divine Father and Super Energy Gayatri Is Our Divine Mother

SUPER POWER YAJNA IS OUR DIVINE FATHER AND SUPER ENERGY GAYATRI IS OUR DIVINE MOTHER ORIGINALLY WRITTEN IN HINDI BY LATE YUGA RISHI SHRIRAM SHARMA ACHARYA (FOUNDER OF THE ALL WORLD GAYATRI FAMILY, WEBSITE: WWW.AWGP.ORG ) COMPILED AND PUBLISHED ON THE INTERNET BY MR ASHOK N. RAWAL TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH BY MS/ HEENA A. KAPADIA (M.Sc., M.Phil) CONTENTS INTRODUCTION TO SUPER POWER YAJNAS INTRODUCING VEDMURTI TAPONISHTHA YUGA RISHI PANDIT SHRIRAM SHARMA ACHARYA CHAPTER 1 WHAT EXACTLY ARE SUPER POWER YAJNAS? CHAPTER 2 WHY ARE SUPER ENERGY YAJNAS EXECUTED BY HUMAN BEINGS ONLY? CHAPTER 3 TRUE SACRED YAJNA SENTIMENTS ARE GOD WORSHIP AND PHILANTHROPHY CHAPTER 4 AUGMENTING AND AMPLYING GREAT DIVINE PRINCIPLES IN A MANIFOLD MANNER CHAPTER 5 MATERIAL BENEFITS ATTAINED VIA SUPER ENERGY SUPER POWER YAJNAS CHAPTER 6 AUGMENTING GOOD HEALTH AND WARDING OFF VARIOUS DISEASES VIA SUPER POWER YAJNAS CHAPTER 7 A DESCRIPTION OF SUPER POWER YAJNAS THAT ARE SPECIAL IN NATURE CHAPTER 8 GODDESS MOTHER GAYATRI WHO IMBUES HER DEVOTEES’ SOUL WITH SUPER DIVINE POWERS CHAPTER 9 TRIPADA OR 3 LEGGED SUPER ENERGY GAYATRI CHAPTER 10 THE PROFOUND MEANING OF SUPER POWER GAYATRI CHAPTER 11 SOLAR BASED SPIRITUAL PRACTICES CALLED SURYA SADHANA CHAPTER 12 REMAINING ALIVE VIA SOLAR ENERGY FOR 411 DAYS WITHOUT FOOD AND WATER CHAPTER 13 SOLAR BASED SPIRITUAL PRACTICES OR SURYA SADHANA-ITS TECHNIQUE AND METHODOLOGY CHAPTER 14 THE BRILLIANT SUN IS OUR VERY LIFE AND OUR PRANA ENERGY CHAPTER 15 THE BRILLIANT SUN BESTOWS ON US OUR VERY LIFE FORCE OR PRANA ENERGY CHAPTER 16 THE SHINING -

Government of India Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF ENVIRONMENT, FOREST AND CLIMATE CHANGE LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO. 1432 TO BE ANSWERED ON 25.07.2017 Grant to NGOs 1432. SHRI A. ANWHAR RAAJHAA: Will the Minister of ENVIRONMENT, FOREST AND CLIMATE CHANGE be pleased to state: (a) whether the Union Government has granted/sanctioned financial assistance to any social organization to carry out activities relating to welfare of animals in the country; and (b) if so, the details thereof, organization and State-wise? ANSWER MINISTER FOR ENVIRONMENT, FOREST AND CLIMATE CHANGE (DR. HARSH VARDHAN) a) Government provides financial assistance to eligible Animal Welfare Organizations under animal welfare schemes through Animal Welfare Board of India (AWBI), Chennai. Details of the schemes are as under:- i. AWBI Plan Scheme: Under the scheme financial assistance is provided to animal welfare organizations for maintaining the stray animal in distress and their treatment, human education programmes for welfare of animals, etc. ii. Scheme for Provision of Shelter House for Animals: Under the scheme financial assistance is provided to NGOs/AWOs for establishment and maintenance of shelter houses for care and protection of uncared animals. iii. Scheme for Animal Birth Control and Immunization of Stray Dogs: The scheme aims to facilitate sterilization and immunization of stray dogs through the NGOs/Society for Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (SPCAs) throughout the country. iv. Scheme for Ambulance Services to Animals in Distress: Under this scheme, ambulance/rescue vehicles are provided to the NGOs/AWOs/ Gaushalas working in the field of animal welfare. v. Scheme for Relief to Animals during Natural Calamity and Unforeseen circumstances: Under this scheme, financial assistance is extended to AWOs, State Governments/ UTs, local bodies working in the affected areas for providing relief to the animals affected during natural calamities and for relief of animals rescued from illegal transportation, slaughter, circuses etc. -

Updatedrecognised Awos-05.09.2019

Sl No Code No Name of the AWO Address Place State Tel_No AP002/1964 Peela Ramakrishna Memorial Jeevraksha Guntur 522003 ANDHRA PRADESH 1 Sangham 2 AP003/1971 Animal Welfare Society 27 & 37 Main Road Visakapattinam 530 002 ANDHRA PRADESH 560501 3 AP004/1972 SPCA Kakinada SPCA Complex, Ramanayyapeta, Kakinada 533 003 ANDHRA PRADESH 0884-2375163 AP005/1985 Vety. Hospital Campus, Railway Feeders 4 District Animal Welfare Committee Rd Nellore 524 004 ANDHRA PRADESH 0861-331855 5 AP006/1985 District Animal Welfare Committee Guttur 522 001 ANDHRA PRADESH 6 AP007/1988 Eluru Gosamrakshana Samiti Ramachandra Rao Pet Elluru 534 002 ANDHRA PRADESH 08812-235518 7 AP008/1989 District Animal Welfare Committee Kurnool 518 001 ANDHRA PRADESH AP010/1991 55,Bajana Mandir,Siru Gururajapalam T.R Kandiga PO, Chitoor Dt. 8 Krishna Society for Welfare of Animals Vill. 517571 ANDHRA PRADESH 9 AP013/1996 Shri Gosamrakshana Punyasramam Sattenapalli - 522 403 Guntur Dist. ANDHRA PRADESH 08641-233150 AP016/1998 Visakha Society for Protection and Care of 10 Animals 26-15-200 Main Road Visakapattinam 530 001 ANDHRA PRADESH 0891-2716124 AP017/1998 International Animal & Birds Welfare Teh.Penukonda,Dist.Anantapur 11 Society 2/152 Main Road, Guttur 515 164 ANDHRA PRADESH 08555-284606 12 AP018/1998 P.S.S. Educational Development Society Pamulapadu, Kurnool Dist. Erragudur 518 442 ANDHRA PRADESH 13 AP019/1998 Society for Animal Protection Thadepallikudem ANDHRA PRADESH AP020/1999 Chevela Rd, Via C.B.I.T.R.R.Dist. PO Enkapalli, Hyderabad 500 14 Shri Swaminarayan Gurukul Gaushala Moinabad Mandal 075 ANDHRA PRADESH AP021/1999 Royal Unit for Prevention of Cruelty to 15 Animals Jeevapranganam, Uravakonda-515812 Dist. -

Taxation of Charitable Trusts and Institutions - a Study

TAXATION OF CHARITABLE TRUSTS AND INSTITUTIONS - A STUDY [Based on the law as amended by the Finance Act, 2008] Direct Taxes Committee The Institute of Chartered Accountants of India (Set up by an Act of Parliament) New Delhi THE INSTITUTE OF CHARTERED ACCOUNTANTS OF INDIA All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior permission in writing, from the publisher. Website : www.icai.org E-mail : [email protected] First Edition : January, 1978 Reprinted : July, 1978 Second Revised Edition : October, 1980 Third Revised Edition : March, 1984 Fourth Revised Edition : May, 1999 Fifth Revised Edition : January, 2002 Sixth Edition : February, 2009 Price : Rs. 300/- ISBN No : 978-81-8441-213-0 Published by : The Publication Department on behalf of CA. Mukta K. Verma, Secretary, Direct Taxes Committee, The Institute of Chartered Accountants of India, A-94/4, Sector-58 Noida -201 301. Printed by : Sahitya Bhawan Publications, Hospital Road, Agra 282 003. February/2009/1000 Copies ii FOREWORD TO THE SIXTH EDITION Taxation of “Charitable trusts and Institutions” is an important area in the Income-tax Act. Since the medium of charitable trusts is widely perceived as a toll of tax planning, the government has progressively made the law relating to taxation of charitable trust very strict. In the recent past there have been many amendments in the law through which the Government has tried to bring the anonymous donations made to these trusts under the tax net. -

![F 9Vcr]UVU Vize Wc`^ 7]Vve Decvve 6ZHHSLQJ VQRRSLQJ](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9226/f-9vcr-uvu-vize-wc-7-vve-decvve-6zhhslqj-vqrrslqj-4449226.webp)

F 9Vcr]UVU Vize Wc`^ 7]Vve Decvve 6ZHHSLQJ VQRRSLQJ

& C"# *.!D !D D SIDISrtVUU@IB!&!!"&#S@B9IV69P99I !%! %! ' -/&*-%0' 01212 3 +,-' ./ 0,4 .$ ":+:56"62 "/+E ;/ <+5: +,/,6":#"52: ! " # ""#$!#% %#%#% ,5, "": $5"25 :"5 </"#5;, 2#626"F6, #&#%%# G 2 +$,%- --. ?'- G : * " ! ##"#102 # ,:;#:<6 digital versions of English newspaper National Herald, n a big setback for the Hindi’s Navjivan and Urdu’s ICongress, the Delhi High Qaumi Awaz commenced pub- Court on Tuesday ordered the lication in 2016-17. The week- eviction of the publisher of ly newspaper National Herald Congress mouthpiece National resumed publication on Herald from Herald House, September 24 last year, AJL had the headquarters of the news- said, adding that the Hindi paper, within two weeks, dis- weekly newspaper Sunday missing the petition filed by the Navjivan was also being pub- publisher Associated Journals lished since October this year Limited (AJL). from the same premises. ,:;#:<6 Finding no irregularity in Later in the evening, wel- the Urban Development coming the judgment, the massive uproar erupted Ministry’s Land and Urban Development Ministry Ainside and outside Development Office (L&DO), said, “It was found by the Parliament over the the judgment said there is total inspecting team of the Ministry Government’s decision to violation of the lease agreement on April 09, 2018 that no empower several investigating by the publisher who is hold- printing press was functioning agencies to intercept and mon- " # ing the building for past 56 at any floor of the premises and itor data on computers. While $& ' ( years. no paper stock was found any- the Opposition accused the The court also said AJL’s where.” Government of turning India Ministry for the first time ever Anand Sharma is making a takeover by Sonia Gandhi and “In earlier inspection also, into a surveillance State, after the rules were framed mountain where even a mole- Rahul Gandhi’s floated firm the basement where press Finance Minister Arun Jaitley almost a decade ago. -

Regular Grant Released in 2007-2008

SL NO CODE NO NAME OF THE AWO Amout Released ANDHRA PRADESH AP004/1972 SPCA Kakinada 40000 AP007/1988 Eluru Gosamrakshana Samiti 50000 AP011/1993 Blue Cross of Hyderabad 90000 AP016/1998 Visakha SPCA 150000 AP017/1998 International Animal & Birds Welfare Society 60000 AP021/1999 Royal Unit for Prevention of Cruelty to Animals 30000 AP033/2000 Shri Mahavir Gaushala Foundation Trust 60000 AP037/2000 Foundation for Animals Trust 80000 AP038/2000 Society of Animal Welfare 10000 AP064/2002 Karuna Society for Animals and Nature 100000 AP072/2002 SHRI VIJAYAWADA GO SAMRAKSHAN SANGHAM 80000 AP088/2005 Sahayog Organisation 50000 AP093/2006 Sai Blue Cross Society 30000 AP096/2006 Social Economic for Labour and Community Training (SELECT) 60000 AP100/2007 Abhya Gau Sewa Sansthan 10000 AP101/2008 Animal Welfare Society 15000 ASSAM AS003/1993 Blue Cross Society of Assam 30000 AS006/1998 Assam Animal Husbandry & Vety. Service Association 10000 BIHAR & JHARKHAND BH003/1991 Shri Tatanagar Gaushala 125000 BH010/1999 Shri Ganga Gaushala 50000 BH014/1999 Jamshedpur Animal Welfare Society 10000 BH017/2000 Rashtriya Goraksha Sangh 40000 BH037/2007 Helping Organisation for Environment & Animal Trust (Hope & Animal Tru 10000 GUJARAT GJ007/1987 Smt.Sheni Memorial Charitable Trust 30000 GJ009/1991 Shri Dhrol Gaushala & Panjrapole 50000 GJ010/1991 Shri Dhrangadhara Panjrapole 150000 GJ013/1991 Seth Aanandji Kushalchandji Khodo Dhol Panjrapole Sansthan 50000 GJ016/1991 Shri Vrindhavan Gaushala Jivdaya Trust 100000 GJ019/1991 Shri Sidhpur Mahajan Panjarapole 70000 -

List of AWBI Recognized Awos

Animal Welfare Board of India List of recognised Animal Welfare Organizations as on 12.03.2021 Sl No Code No Name of the AWO Address Place State 1 AP002/1964 Peela Ramakrishna Memorial Jeevraksha Sangham Guntur 522003 ANDHRA PRADESH 2 AP003/1971 Animal Welfare Society 27 & 37 Main Road Visakapattinam 530 002 ANDHRA PRADESH 3 AP004/1972 SPCA Kakinada SPCA Complex, Ramanayyapeta, Kakinada 533 003 ANDHRA PRADESH 4 AP005/1985 District Animal Welfare Committee Vety. Hospital Campus, Railway Feeders Rd Nellore 524 004 ANDHRA PRADESH 5 AP006/1985 District Animal Welfare Committee Guttur 522 001 ANDHRA PRADESH 6 AP007/1988 Eluru Gosamrakshana Samiti Ramachandra Rao Pet Elluru 534 002 ANDHRA PRADESH 7 AP008/1989 District Animal Welfare Committee Kurnool 518 001 ANDHRA PRADESH 8 AP010/1991 Krishna Society for Welfare of Animals 55,Bajana Mandir,Siru Gururajapalam Vill. T.R Kandiga PO, Chitoor Dt. 517571 ANDHRA PRADESH 9 AP013/1996 Shri Gosamrakshana Punyasramam Sattenapalli - 522 403 Guntur Dist. ANDHRA PRADESH 10 AP016/1998 Visakha Society for Protection and Care of Animals 26-15-200 Main Road Visakapattinam 530 001 ANDHRA PRADESH 11 AP017/1998 International Animal & Birds Welfare Society 2/152 Main Road, Guttur Teh.Penukonda,Dist.Anantapur 515 164ANDHRA PRADESH 12 AP018/1998 P.S.S. Educational Development Society Pamulapadu, Kurnool Dist. Erragudur 518 442 ANDHRA PRADESH 13 AP019/1998 Society for Animal Protection Thadepallikudem ANDHRA PRADESH 14 AP020/1999 Shri Swaminarayan Gurukul Gaushala Chevela Rd, Via C.B.I.T.R.R.Dist. Moinabad Mandal PO Enkapalli, Hyderabad 500 075 ANDHRA PRADESH 15 AP021/1999 Royal Unit for Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Jeevapranganam, Uravakonda-515812 Dist. -

Dr. Ram Manohar Lohia Avadh University, Faizabad ======Result of B.A

DR. RAM MANOHAR LOHIA AVADH UNIVERSITY, FAIZABAD ================================================ RESULT OF B.A. PART I - 2011 ( BACK PAPER ) KISAN P.G. COLLEGE,BAHRAICH REGULAR: PASSED: 301901, 301903, 301904, 301911, 301912, 301913, 301917, 301921, 301929, 301937, 301940, 301941, 301942, 301943, 301944, 301948, 301950, 301954, 301956, 301961, 301962, 301963, 301965, 301969, 301970, 301976, 301982, 301985, 301988, 301989, 301993, 301996, 301997, 301999, 302000, 302008, 302009, 302018, 302024, 302032, 302037, 302040, 302043, 302053, 302055, 302056, 302057, 302063, 302079, 302080, 302083, 302087, 302089, 302092, 302100, 302109, 302113, 302122, 302124, 302125, 302133, 302138, 302143, 302144, 302151, 302153, 302155, 302157, 302159, 302174, 302177, 302192, 302199, 302204, 302205, 302214, 302217, 302220, 302224, 302243, 302246, 302248, 302250, 302251, 302256, 302262, 302263, 302264, 302278, 302280, 302292, 302314, 302329, 302338, 302339, 302343, 302356, 302359, 302373, 302393, 302397, 302402, 302403, 302416, 302425, 302429, 302435, 302438, 302442, 302443, 302452, 302465, 302469, 302474, 302475, 302510, 302525, 302541, 302553, 302558, 302563, 302564, 302565, 302573, 302574, 302589, 302594, 302616, 302623, 302626, 302629, 302631, 302638, 302647, 302662, 302664, 302667, 302668, 302674, 302675, 302684, 302691, 302692, 302697, 302704, 302707, 302711, 302740, 302751, 302756, 302758, 302762, 302764, 302766, 302768, 302770, 302771, 302781, 302784, 302786, 302793, 302801, 302813, 302819, 302820, 302822, 302838, 302842, 302865, 302876, 302897, 302909, -

Guru Et Politique En Inde. Des Éminences Grises À Visage Découvert ? In: Politix

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by SPIRE - Sciences Po Institutional REpository Christophe Jaffrelot Guru et politique en Inde. Des éminences grises à visage découvert ? In: Politix. Vol. 14, N°54. Deuxième trimestre 2001. pp. 75-94. Citer ce document / Cite this document : Jaffrelot Christophe. Guru et politique en Inde. Des éminences grises à visage découvert ?. In: Politix. Vol. 14, N°54. Deuxième trimestre 2001. pp. 75-94. doi : 10.3406/polix.2001.1155 http://www.persee.fr/web/revues/home/prescript/article/polix_0295-2319_2001_num_14_54_1155 Résumé Guru et politique en Inde : des éminences grises à visage découvert ? Christophe Jaffrelot La configuration classique du pouvoir en Inde associe au souverain un conseiller spirituel de caste brahmane. Ce schéma traditionnel a perdu tout droit de cité dans le cadre de la sécularisation de l'Etat après 1947. Néanmoins, des hommes politiques, comme Indira Gandhi, ont continué d'entretenir d'étroites relations avec leur guru et ont volontiers rendues publiques ces relations lorsque cela améliorait leur popularité. En fait, de telles relations se révélaient illégitimes lorsque les guru en question étaient des tantriques ou lorsqu'ils entretenaient des liens illicites avec le monde criminel. Le rapport au pouvoir qu'entretient le RSS (Rashtriya swayamsevak sangh, Association des volontaires nationaux) est calqué sur le modèle traditionnel puisque cette organisation se veut le guru du pouvoir. L'accès de « son » parti politique, le BJP, au gouvernement lui en donne la possibilité depuis 1998. Après s'être contenté de conseiller le pouvoir en coulisses, le RSS sort de plus en plus de l'ombre en partie parce que le premier ministre Vajpayee peut trouver avantage à se prévaloir de ses liens privilégiés avec une organisation connue pour sa pureté doctrinale et son intégrité. -

UZR Cv[`Ztvd Re 4YR F¶D Wvre

, - G6 + *& H % & H H /,0/)1234 ?, *. @A'//! ? %: + '"#()* !+(%% !"#$%& !"#$ $% E::667,6C8 :<679 9C::6D7 %#& %' '%#! 6C6;6#;9 '% ' !%#(%' 733,9,# 799:7: '% # )'%% *+%) %% % 56%57518& 1494F , ., R (+ + O P & 9:;:,# & 9:;:,# silver medal and Saikhom Q Ongbi Tombi Leima has strug- s fighting rages in historic silver medal and a gled to stop her tears from AAfghanistan, the Indian Aradiant smile were not the flowing ever since. embassy there on Saturday only eye-catching things about “I saw the earrings on TV, said the situation “remains R Mirabai Chanu on Saturday, I gave them to her in 2016 dangerous” and advised all her gold earrings shaped like before the (Rio) Olympics. I Indian nationals there to exer- Olympic rings were as striking, have made it for her from the cise caution. a gift from her mother who gold pieces and savings I have The advisory came days sold her own jewellery for so that it brings luck and suc- after the IAF planes evacuated them five years ago. cess,” Leima told PTI from her more than 50 diplomatic staff The hope was that the ear- home in Manipur where a of the Indian consulate in rings would bring her “good considerable number of rela- Kandhar . luck”. It didn’t happen in the tives, friends and well-wishers The note of caution by the Rio 2016 Games but Chanu gathered to watch Chnau script embassy in Kabul on Saturday made the little sacrifice count history in Tokyo. urged Indians staying, visiting, in Tokyo this morning with a Continued on Page 9 and working in Afghanistan to exercise utmost vigilance at all times and avoid all non-essen- confused she had felt during * tial travel as security situation her debut at the biggest stage.