National Treasure 3: the Lost Colony

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cherokees in Arkansas

CHEROKEES IN ARKANSAS A historical synopsis prepared for the Arkansas State Racing Commission. John Jolly - first elected Chief of the Western OPERATED BY: Cherokee in Arkansas in 1824. Image courtesy of the Smithsonian American Art Museum LegendsArkansas.com For additional information on CNB’s cultural tourism program, go to VisitCherokeeNation.com THE CROSSING OF PATHS TIMELINE OF CHEROKEES IN ARKANSAS Late 1780s: Some Cherokees began to spend winters hunting near the St. Francis, White, and Arkansas Rivers, an area then known as “Spanish Louisiana.” According to Spanish colonial records, Cherokees traded furs with the Spanish at the Arkansas Post. Late 1790s: A small group of Cherokees relocated to the New Madrid settlement. Early 1800s: Cherokees continued to immigrate to the Arkansas and White River valleys. 1805: John B. Treat opened a trading post at Spadra Bluff to serve the incoming Cherokees. 1808: The Osage ceded some of their hunting lands between the Arkansas and White Rivers in the Treaty of Fort Clark. This increased tension between the Osage and Cherokee. 1810: Tahlonteeskee and approximately 1,200 Cherokees arrived to this area. 1811-1812: The New Madrid earthquake destroyed villages along the St. Francis River. Cherokees living there were forced to move further west to join those living between AS HISTORICAL AND MODERN NEIGHBORS, CHEROKEE the Arkansas and White Rivers. Tahlonteeskee settled along Illinois Bayou, near NATION AND ARKANSAS SHARE A DEEP HISTORY AND present-day Russellville. The Arkansas Cherokee petitioned the U.S. government CONNECTION WITH ONE ANOTHER. for an Indian agent. 1813: William Lewis Lovely was appointed as agent and he set up his post on CHEROKEE NATION BUSINESSES RESPECTS AND WILL Illinois Bayou. -

Trailword.Pdf

NPS Form 10-900-b OMB No. 1024-0018 (March 1992) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form This form is used for documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in How to Complete the Multiple Property Documentation Form (National Register Bulletin 16B). Complete each item by entering the requested information. For additional space, use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items. _X___ New Submission ____ Amended Submission ======================================================================================================= A. Name of Multiple Property Listing ======================================================================================================= Historic and Historical Archaeological Resources of the Cherokee Trail of Tears ======================================================================================================= B. Associated Historic Contexts ======================================================================================================= (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period for each.) See Continuation Sheet ======================================================================================================= C. Form Prepared by ======================================================================================================= -

Great Cloud of Witnesses.Indd

A Great Cloud of Witnesses i ii A Great Cloud of Witnesses A Calendar of Commemorations iii Copyright © 2016 by The Domestic and Foreign Missionary Society of The Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America Portions of this book may be reproduced by a congregation for its own use. Commercial or large-scale reproduction for sale of any portion of this book or of the book as a whole, without the written permission of Church Publishing Incorporated, is prohibited. Cover design and typesetting by Linda Brooks ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-962-3 (binder) ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-966-1 (pbk.) ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-963-0 (ebook) Church Publishing, Incorporated. 19 East 34th Street New York, New York 10016 www.churchpublishing.org iv Contents Introduction vii On Commemorations and the Book of Common Prayer viii On the Making of Saints x How to Use These Materials xiii Commemorations Calendar of Commemorations Commemorations Appendix a1 Commons of Saints and Propers for Various Occasions a5 Commons of Saints a7 Various Occasions from the Book of Common Prayer a37 New Propers for Various Occasions a63 Guidelines for Continuing Alteration of the Calendar a71 Criteria for Additions to A Great Cloud of Witnesses a73 Procedures for Local Calendars and Memorials a75 Procedures for Churchwide Recognition a76 Procedures to Remove Commemorations a77 v vi Introduction This volume, A Great Cloud of Witnesses, is a further step in the development of liturgical commemorations within the life of The Episcopal Church. These developments fall under three categories. First, this volume presents a wide array of possible commemorations for individuals and congregations to observe. -

Creating a Sense of Communityamong the Capital City Cherokees

CREATING A SENSE OF COMMUNITYAMONG THE CAPITAL CITY CHEROKEES by Pamela Parks Tinker A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of George Mason University in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Interdisciplinary Studies Committee: ____________________________________ Director ____________________________________ ____________________________________ ____________________________________ Program Director ____________________________________ Dean, College of Humanities and Social Sciences Date:________________________________ Spring 2016 George Mason University Fairfax, VA Creating a Sense Of Community Among Capital City Cherokees A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Interdisciplinary Studies at George Mason University By Pamela Parks Tinker Bachelor of Science Medical College of Virginia/Virginia Commonwealth University 1975 Director: Meredith H. Lair, Professor Department of History Spring Semester 2016 George Mason University Fairfax, Virginia Copyright 2016 Pamela Parks Tinker All Rights Reserved ii Acknowledgements Thanks to the Capital City Cherokee Community for allowing me to study the formation of the community and for making time for personal interviews. I am grateful for the guidance offered by my Thesis Committee of three professors. Thesis Committee Chair, Professor Maria Dakake, also served as my advisor over a period of years in planning a course of study that truly has been interdisciplinary. It has been a joyful situation to be admitted to a variety of history, religion and spirituality, folklore, ethnographic writing, and research courses under the umbrella of one Master of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies program. Much of the inspiration for this thesis occurred at George Mason University in Professor Debra Lattanzi Shutika’s Folklore class on “Sense of Place” in which the world of Ethnography opened up for me. -

Chickamauga Names

Chickamaugas / Dragging Canoe Submitted by Nonie Webb CHICKAMAUGAS Associated with Dragging Canoe ARCHIE, John Running Water Town – trader in 1777. BADGER “Occunna” Said to be Attakullakullas son. BENGE, Bob “Bench” b. 1760 Overhills. D. 1794 Virginia. Son of John Benge. Said to be Old Tassels nephew. Worked with Shawnees, and Dragging Canoe. BENGE, John Father of Bob Benge. White trader. Friend of Dragging Canoe. BENGE, Lucy 1776-1848 Wife of George Lowry. BIG FELLOW Worked with John Watts ca. 1792. BIG FOOL One of the head men of Chicamauga Town. BLACK FOX “Enola” Principal Headman of Cherokee Nation in 1819. Nephew to Dragging Canoe. BLOODY FELLOW “Nentooyah” Worked with Dragging Canoe BOB Slave Owner part of Chicamaugas. (Friend of Istillicha and Cat) BOOT “Chulcoah” Chickamauga. BOWL “Bold Hunter” or “Duwali” Running Water Town. b. 1756l- Red hair – blue eyes. Father was Scott. Mother was Cherokee.1768 d, Texas. (3 wives) Jennie, Oolootsa, & Ootiya. Headman Chickamaugas. BREATH “Untita” or Long Winded. Headman of Nickajack Town. d. Ore’s raid in 1794. 1 Chickamaugas / Dragging Canoe Submitted by Nonie Webb BROOM. (see Renatus Hicks) BROWN, James Killed by Chickamaugas on [Murder of Brown Family]….Tennessee River in 1788. Wife captured. Some of Sons and Son in Laws Killed. Joseph Brown captured. Later Joseph led Ore’s raid on Nickajack & Running Water Town in 1794. (Brown family from Pendleton District, S. C.) BROWN, Thomas Recruited Tories to join Chickamaugas. Friend of John McDonald. CAMERON, Alexander. “Scotchee” Dragging Canoe adopted him as his “brother”. Organized band of Torries to Work with the Chicamaugas. CAMPBELL, Alexander. -

Hclassification

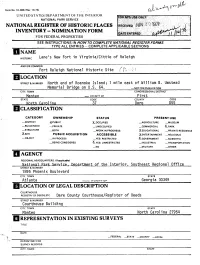

Form No. 10-306 (Rev. 10-74) J, UN1TEDSTATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR FEDERAL PROPERTIES SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ____________TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS___________ | NAME HISTORIC Lane's New Fort in Virginia/Cittie of Raleigh AND/OR COMMON ~ Fort Raleigh National Historic Site ( \\ ^f I____________ LOCATION STREETS.NUMBER North end of Roanoke Island; 1 mile east of William B. Umstead Memorial Bridge on U.S. 64. —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Manteo — VICINITY OF First STATE CODE COUNTY CODE North Carolina 37 Dare 055 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT ^.PUBLIC X-OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM _BUILDING(S) —PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED _ COMMERCIAL 2L.PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS -^.EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE XsiTE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE JCENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _ IN PROCESS —YES. RESTRICTED X.GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED X_YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: [AGENCY REGIONAL HEADQUARTERS: (If applicable) National Park Service. Department of the Interior, Southeast Regional Office STREET 8» NUMBER 1895 Phoenix Boulevard CITY. TOWN STATE Atlanta VICINITY OF Georgia 30349 LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC. Dare County Courthouse/Register of Deeds STREET & NUMBER Courthouse Building CITY, TOWN STATE Manteo North Carolina 27954 TITLE DATE —FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL CITY. TOWN STATE DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —XEXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X.ORIGINALSITE —GOOD —RUINS JCALTERED —MOVED DATE- —FAIR —UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The boundaries of Fort Raleigh National Historic Site include 159 acres. However, most of this acreage is either developed area, being managed as a natural area or the Elizabethan Gardens maintained by the Garden Club of North Carolina. -

World Stage Curriculum

World Stage Curriculum Washington Irving’s Tour 1832 TEACHER You have been given a completed world stage and a world stage that your students can complete. This world stage is a snapshot of the world with Oklahoma, Cherokee Nation and Muscogee Creek Nation, at its center. The Pawnee, Comanche, and Kiowa were out to the west. Europe is to the north and east. Africa is to the south and east. South America is south and a bit east. Asia and the Pacific are to the west. Use a globe to show your students that these directions are accurate. Students - Directions 1. Your teacher will assign one of these actors to you. 2. After research, note the age of the actor in 1832, the year that Irving, Ellsworth, Pourtalès, and Latrobe took a Tour on the Oklahoma prairies. 3. Place the name and age of the actor in the right place on the World Stage. 4. Write a biographical sketch about the actor. 5. Make a report to the class, sharing the biographical sketch, the age of the actor in 1832, and the place the actor was at that time. 6. Listen to all the other reports and place all of the actors in their correct locations with their correct ages in 1832. Students - Information 1. The majority of the characters can be found in your public library in biographies and encyclopedia. You will need a library card to access this information. There is enough information about each actor for a biographical sketch. 2. Other actors can be found on the Internet. -

Tar Heel Junior Historian

by Sandra Boyd* More than four hundred years ago, and children. Also aboard were two Indians, Europeans wanted to set up Manteo and Wanchese, who had gone to colonies in the New World. For England with Raleigh's previous expedition them, the New World meant the present- and were returning to their home. The pilot day continents of North was a Spaniard, Simon Fernando, and the and South America. What challenging times those must have been! Sir Walter Raleigh, an adventurous English gentleman, sent a group of men to explore the New World. A later expedition established a settlement on Roanoke Island, on the North Carolina coast. In 1586, after enduring winter hardships, lack of food, and disagreements with the Indians, survivors of this colony returned home to England with Sir Francis Drake. Then Raleigh decided to send a second group of colonists. On The baptism of Virginia Dare. April 26,1587, a small fleet set sail from England, hoping to establish governor of the new colony was John White. the first permanent English settlement in the Among the colonists were Governor White's New World. daughter, Eleanor, and her husband, This second group of colonists differed Ananias Dare. The voyage took longer than from the first because it included not only the usual six weeks, and the ships finally men but also women and children. It would anchored off Roanoke Island on July 22. be a permanent colony. The little fleet Once the colonists landed, they began consisted of the ship Lyon, a flyboat (a fast, repairing the houses already there and flat-bottomed boat capable of maneuvering started building new homes. -

Manteo Harbor Report

A CULTURAL RESOURCE EVALUATION OF SUBMERGED LANDS AFFECTED BY THE 400TH ANNIVERSARY CELEBRATION Manteo, North Carolina Conducted By Underwater Archaeology Branch North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources Richard W. Lawrence, Head Leslie S. Bright Mark Wilde-Ramsing Report Prepared by Mark Wilde-Ramsing November, 1983 Abstract Field investigations of the submerged bottom lands at Manteo, North Carolina were carried out by the Underwater Archaeology Branch, Division of Archives and History, Department of Cultural Resources. The purpose of these investigations was to identify historically and/or archaeologically significant cultural materials lying within the area to be affected by construction of a bridge and canal system and berthing area proposed for the 400th Anniversary Celebration (1984 to 1987) on Roanoke Island. Initially, a systematic survey of the project area was performed using a proton precession magnetometer to isolate magnetic disturbances, any of which might be generated by cultural material. Following this, a diving and probing search was conducted on isolated magnetic targets to determine the source. With the exception of the remains of a sunken vessel, Underwater Site #0001ROS, all magnetic disturbances were attributed to cultural debris of recent origin (twentieth century) and were determined historically and archaeologically insignificant. Recommendations for the sunken vessel located on the south side of the proposed berthing area are (1) complete avoidance of the site during construction activities, or (2) further -

US History- Sweeney

©Java Stitch Creations, 2015 Part 1: The Roanoke Colony-Background Information What is now known as the lost Roanoke Colony, was actually the third English attempt at colonizing the eastern shores of the United States. Following through with his family's thirst for exploration, Queen Elizabeth I of England granted Sir Walter Raleigh a royal charter in 1584. This charter gave him seven years to establish a settlement, and allowed him the power to explore, colonize and rnle, in return for one-fifth of all the gold and silver mined in the new lands. Raleigh immediately hired navigators Philip Amadas and Arthur Barlowe to head an expedition to the intended destination of the Chesapeake Bay area. This area was sought due to it being far from the Spanish-dominated Florida colonies, and it had milder weather than the more northern regions. In July of that year, they landed on Roanoke Island. They explored the area, made contact with Native Americans, and then sailed back to England to prove their findings to Sir Walter Raleigh. Also sailing from Roanoke were two members oflocal tribes of Native Americans, Manteo (son of a Croatoan) and Wanchese (a Roanoke). Amadas' and Barlowe's positive report, and Native American assistance, earned the blessing of Sir Walter Raleigh to establish a colony. In 1585, a second expedition of seven ships of colonists and supplies, were sent to Roanoke. The settlement was somewhat successful, however, they had poor relations with the local Native Americans and repeatedly experienced food shortages. Only a year after arriving, most of the colonists left. -

Cherokee 1805-1

TREATY WITH THE CHEROKEE, 1805. Done in the presence of- B. Parke, secretary to the commissioner, Davis Floyd, John Gibson, secretary Indiana Territory, Shadrach Bond, John Griffin, a judge of the Indiana Ter- William Biggs, ritorv, John Johnson, B. Chambers, president of the council, Members house of represen- Jesse B. Thomas, Speaker of the House tatives Indiana Territory, of Representatives. W. Wells, agent of Indian affairs, .Tohn Rice Jones, Vigo, colonel of Knox County Militia, Samuel Gwathmey, John Conner, Pierre Menard, .Joseph Barron, Members legislative council Sworn interpreters. Indiana Territory, ADDITIONAL ARTICLE. It is the intention of the contracting parties, that the boundary line herein directed to be run from the north east corner of the Vincennes tract to the boundary line running from the mouth of the Kentucky river, shall not cross the Embarras or Drift Wood fork of White river, but if it should strike the said fork, such an alteration in the direction of the said line is to be made, as will leave the whole of the said fork in the Indian territory. TREATY WITH THE CHEROKEE, 1805.,.,, __0c_t. _ 25_,_1805 _·_ Articles of a treaty agreed upon between the United States of America, 7 stat., 93. by theircornm,i,Ssioners Return J. Meigs rmd Daniel Smith, appointed 2/f~~ation, Apr. to holil conferences with the Cherokee lnd1'.ans, for the JJurpose Q/' · arranqing certain interesting rnatterw with the said Clterokees, of t!ie oru, part, and the undersigned ch1'.efs and head rnen of the said nation, of the other part. · Former treaties rec- ARTICLE I. -

Newsletter of the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail Partnership • Spring 2018

Newsletter of the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail Partnership • Spring 2018 – Number 29 Leadership from the Cherokee Nation and the National Trail of Tears Association Sign Memorandum of Understanding Tahlequah, OK Principal Chief Bill John Baker expressed Nation’s Historic Preservation Officer appreciation for the work of the Elizabeth Toombs, whereby the Tribe Association and the dedication of its will be kept apprised of upcoming members who volunteer their time and events and activities happening on talent. or around the routes. The Memo encourages TOTA to engage with The agreement establishes a line for govt. and private entities and routine communications between to be an information source on the Trail of Tears Association and the matters pertaining to Trial resource CHEROKEE NATION PRINCIPAL CHIEF BILL JOHN Cherokee Nation through the Cherokee conservation and protection. BAKER AND THE TRAIL OF TEARS PRESIDENT JACK D. BAKER SIGN A MEMORANDUM OF UNDERSTANDING FORMALIZING THE CONTINUED PARTNERSHIP BETWEEN THE TRAIL OF TEARS ASSOCIATION AND THE CHEROKEE NATION TO PROTECT AND PRESERVE THE ROUTES AS WELL AS EDUCATING THE PUBLIC ABOUT THE HISTORY ASSOCIATED WITH THE TRAIL OF TEARS. Cherokee Nation Principal Chief Bill John Baker and Trail of Tears Association President Jack D. Baker, signed a Memorandum of Understanding on March 1st, continuing a long-time partnership between the association and the tribe. Aaron Mahr, Supt. of the National Trails Intermountain Region, the National Park Service office which oversees the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail said “The Trails Of Tears Association is our primary non-profit volunteer organization on the national historic trail, and the partnership the PICTURED ABOVE: (SEATED FROM L TO R) S.