New Cinema in Turkey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Big World – Reha Erdem and the Magic of Cinema

Markets, Globalization & Development Review Volume 2 Article 8 Number 2 Popular Culture and Markets in Turkey 2017 The iB g World – Reha Erdem and the Magic of Cinema Andreas Treske Bilkent University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/mgdr Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Treske, Andreas (2017) "The iB g World – Reha Erdem and the Magic of Cinema," Markets, Globalization & Development Review: Vol. 2: No. 2, Article 8. DOI: 10.23860/MGDR-2017-02-02-08 Available at: http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/mgdr/vol2/iss2/8http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/mgdr/vol2/iss2/8 This Media Review is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Markets, Globalization & Development Review by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This media review is available in Markets, Globalization & Development Review: http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/mgdr/vol2/iss2/8 The iB g World – Reha Erdem and the Magic of Cinema Andreas Treske Abstract Reha Erdem’s latest film Big Big World (Koca Dünya) was selected for the “Horizons” (“Orizzonti”) section at the 73rd Venice International Film Festival in 2016 and won a prestigious special jury award. The eV nice selection is standing for a tendency to hold on, and celebrate the so-called “World Cinema” along with Hollywood blockbusters and new experimental arthouse films in a festival programming mix, insisting to stop for a moment in time a cinema that is already on the move. -

Antiochia As a Cinematic Space and Semir Aslanyürek As a Film Director from Antiochia

Antiochia As A Cinematic Space and Semir Aslanyürek as a Film Director From Antiochia Selma Köksal, Düzce University, [email protected] Volume 8.2 (2020) | ISSN 2158-8724 (online) | DOI 10.5195/cinej.2020.279 | http://cinej.pitt.edu Abstract This study will look at cinematic representation of Antiochia, a city with multiple identities, with a multi- cultural, long and deep historical background in Turkish director Semir Aslanyürek’s films. The article will focus on Aslanyürek’s visual storytelling through his beloved city, his main characters and his main conflicts and themes in his films Şellale (2001), Pathto House (2006), 7 Yards (2009), Lal (2013), Chaos (2018). Semir Aslanyürek was born in Antiochia in 1956. After completing his primary and secondary education in Antiochia (Hatay), he went to Damascus and began his medical training. As an amateur sculptor, he won an education scholarship with one of his statues for art education in Moscow. After a year, he decided to study on cinema instead of art. Semir Aslanyürek studied Acting, Cinema and TV Film from 1980 to 1986 in the Russian State University of Cinematography (VGIK), Faculty of Film Management, and took master's degree. While working as a professor at Marmara University, Aslanyürek directed feature films and wrote many screenplays. This article will also base its arguments on Aslanyürek's cinematic vision as multi-cultural and as a multi- disciplinary visual artist. Keywords: Antiochia; cinematic space; blind; speechless; war; ethnic conflicts; Semir Aslanyürek New articles in this journal are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 United States License. -

A Reframing of Metin Erksan's Time to Love

Auteur and Style in National Cinema: A Reframing of Metin Erksan's Time to Love Murat Akser University of Ulster, [email protected] Volume 3.1 (2013) | ISSN 2158-8724 (online) | DOI 10.5195/cinej.2013.57 | http://cinej.pitt.edu Abstract This essay will hunt down and classify the concept of the national as a discourse in Turkish cinema that has been constructed back in 1965, by the film critics, by filmmakers and finally by today’s theoretical standards. So the questions we will be constantly asking throughout the essay can be: Is what can be called part of national film culture and identity? Is defining a film part of national heritage a modernist act that is also related to theories of nationalism? Is what makes a film national a stylistic application of a particular genre (such as melodrama)? Does the allure of the film come from the construction of a hero-cult after a director deemed to be national? Keywords: Turkish cinema, national cinema, nation state, Metin Erksan, Yeşilçam New articles in this journal are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 United States License. This journal is published by the University Library System of the University of Pittsburgh as part of its D-Scribe Digital Publishing Program and is cosponsored by the University of Pittsburgh Press. Auteur and Style in National Cinema: A Reframing of Metin Erksan's Time to Love Murat Akser Twenty-five years after its publication in 1989, Andrew Higson’s conceptualization of national cinema in his seminal Screen article has been challenged by other film scholars. -

Cinema and Politics

Cinema and Politics Cinema and Politics: Turkish Cinema and The New Europe Edited by Deniz Bayrakdar Assistant Editors Aslı Kotaman and Ahu Samav Uğursoy Cinema and Politics: Turkish Cinema and The New Europe, Edited by Deniz Bayrakdar Assistant Editors Aslı Kotaman and Ahu Samav Uğursoy This book first published 2009 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2009 by Deniz Bayrakdar and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-0343-X, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-0343-4 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Images and Tables ......................................................................... viii Acknowledgements .................................................................................... ix Preface ........................................................................................................ xi Introduction ............................................................................................. xvii ‘Son of Turks’ claim: ‘I’m a child of European Cinema’ Deniz Bayrakdar Part I: Politics of Text and Image Chapter One ................................................................................................ -

The Honorable Mentions Movies- LIST 1

The Honorable mentions Movies- LIST 1: 1. A Dog's Life by Charlie Chaplin (1918) 2. Gone with the Wind Victor Fleming, George Cukor, Sam Wood (1940) 3. Sunset Boulevard by Billy Wilder (1950) 4. On the Waterfront by Elia Kazan (1954) 5. Through the Glass Darkly by Ingmar Bergman (1961) 6. La Notte by Michelangelo Antonioni (1961) 7. An Autumn Afternoon by Yasujirō Ozu (1962) 8. From Russia with Love by Terence Young (1963) 9. Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors by Sergei Parajanov (1965) 10. Stolen Kisses by François Truffaut (1968) 11. The Godfather Part II by Francis Ford Coppola (1974) 12. The Mirror by Andrei Tarkovsky (1975) 13. 1900 by Bernardo Bertolucci (1976) 14. Sophie's Choice by Alan J. Pakula (1982) 15. Nostalghia by Andrei Tarkovsky (1983) 16. Paris, Texas by Wim Wenders (1984) 17. The Color Purple by Steven Spielberg (1985) 18. The Last Emperor by Bernardo Bertolucci (1987) 19. Where Is the Friend's Home? by Abbas Kiarostami (1987) 20. My Neighbor Totoro by Hayao Miyazaki (1988) 21. The Sheltering Sky by Bernardo Bertolucci (1990) 22. The Decalogue by Krzysztof Kieślowski (1990) 23. The Silence of the Lambs by Jonathan Demme (1991) 24. Three Colors: Red by Krzysztof Kieślowski (1994) 25. Legends of the Fall by Edward Zwick (1994) 26. The English Patient by Anthony Minghella (1996) 27. Lost highway by David Lynch (1997) 28. Life Is Beautiful by Roberto Benigni (1997) 29. Magnolia by Paul Thomas Anderson (1999) 30. Malèna by Giuseppe Tornatore (2000) 31. Gladiator by Ridley Scott (2000) 32. The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring by Peter Jackson (2001) 33. -

Three Monkeys

THREE MONKEYS (Üç Maymun) Directed by Nuri Bilge Ceylan Winner Best Director Prize, Cannes 2008 Turkey / France/ Italy 2008 / 109 minutes / Scope Certificate: 15 new wave films Three Monkeys Director : Nuri Bilge Ceylan Producer : Zeynep Özbatur Co-producers: Fabienne Vonier Valerio De Paolis Cemal Noyan Nuri Bilge Ceylan Scriptwriters : Ebru Ceylan Ercan Kesal Nuri Bilge Ceylan Director of Photography : Gökhan Tiryaki Editors : Ayhan Ergürsel Bora Gökşingöl Nuri Bilge Ceylan Art Director : Ebru Ceylan Sound Engineer : Murat Şenürkmez Sound Editor : Umut Şenyol Sound Mixer : Olivier Goinard Production Coordination : Arda Topaloglu ZEYNOFILM - NBC FILM - PYRAMIDE PRODUCTIONS - BIM DISTRIBUZIONE In association with IMAJ With the participation of Ministry of Culture and Tourism Eurimages CNC COLOUR – 109 MINUTES - HD - 35mm - DOLBY SR SRD - CINEMASCOPE TURKEY / FRANCE / ITALY new wave films Three Monkeys CAST Yavuz Bingöl Eyüp Hatice Aslan Hacer Ahmet Rıfat Şungar İsmail Ercan Kesal Servet Cafer Köse Bayram Gürkan Aydın The child SYNOPSIS Eyüp takes the blame for his politician boss, Servet, after a hit and run accident. In return, he accepts a pay-off from his boss, believing it will make life for his wife and teenage son more secure. But whilst Eyüp is in prison, his son falls into bad company. Wanting to help her son, Eyüp’s wife Hacer approaches Servet for an advance, and soon gets more involved with him than she bargained for. When Eyüp returns from prison the pressure amongst the four characters reaches its climax. new wave films Three Monkeys Since the beginning of my early youth, what has most intrigued, perplexed and at the same time scared me, has been the realization of the incredibly wide scope of what goes on in the human psyche. -

The Space Between: a Panorama of Cinema in Turkey

THE SPACE BETWEEN: A PANORAMA OF CINEMA IN TURKEY FILM LIST “The Space Between: A Panorama of Cinema in Turkey” will take place at the Walter Reade Theater at Lincoln Center from April 27 – May 10, 2012. Please note this list is subject to change. AĞIT a week. Subsequently, Zebercet begins an impatient vigil Muhtar (Ali Şen), a member of the town council, sells a piece and, when she does not return, descends into a psychopathic of land in front of his home to Haceli (Erol Taş), a land ELEGY breakdown. dispute arises between the two families and questions of Yılmaz Güney, 1971. Color. 80 min. social and moral justice come into play. In Ağıt, Yılmaz Güney stars as Çobanoğlu, one of four KOSMOS smugglers living in a desolate region of eastern Turkey. Reha Erdem, 2009. Color. 122 min. SELVİ BOYLUM, AL YAZMALIM Greed, murder and betrayal are part of the everyday life of THE GIRL WITH THE RED SCARF these men, whose violence sharply contrasts with the quiet Kosmos, Reha Erdem’s utopian vision of a man, is a thief who Atıf Yılmaz, 1977. Color. 90 min. determination of a woman doctor (Sermin Hürmeriç) who works miracles. He appears one morning in the snowy border attends to the impoverished villagers living under constant village of Kars, where he is welcomed with open arms after Inspired by the novel by Kyrgyz writer Cengiz Aytmatov, Selvi threat of avalanche from the rocky, eroded landscape. saving a young boy’s life. Despite Kosmos’s curing the ill and Boylum, Al Yazmalım tells the love story of İlyas (Kadir İnanır), performing other miracles, the town begins to turn against a truck driver from Istanbul, his new wife Asya (Türkan Şoray) him when it is learned he has fallen in love with a local girl. -

The Honorable Mentions Movies – LIST 3

The Honorable mentions Movies – LIST 3: 1. Modern Times by Charles Chaplin (1936) 2. Pinocchio by Hamilton Luske et al. (1940) 3. Late Spring by Yasujirō Ozu (1949) 4. The Virgin Spring by Ingmar Bergman (1960) 5. Charade by Stanley Donen (1963) 6. The Soft Skin by François Truffaut (1964) 7. Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? by Mike Nichols (1966) 8. Dog Day Afternoon by Sidney Lumet (1975) 9. Love Unto Death by Alain Resnais (1984) 10. Kiki's Delivery Service by Hayao Miyazaki (1989) 11. Bram Stoker's Dracula by Francis Ford Coppola (1992) 12. Léon: The Professional by Luc Besson (1994) 13. Princess Mononoke by Hayao Miyazaki (1997) 14. Fight Club by David Fincher (1999) 15. Rosetta by Jean-Pierre Dardenne, Luc Dardenne (1999) 16. The Ninth Gate by Roman Polanski (1999) 17. O Brother, Where Art Thou? by Ethan Coen, Joel Coen (2000) 18. The Return Andrey Zvyagintsev (2003) 19. The Sea Inside by Alejandro Amenábar (2004) 20. Broken Flowers by Jim Jarmusch (2005) 21. Climates by Nuri Bilge Ceylan (2006) 22. The Prestige by Christopher Nolan (2006) 23. The Class by Laurent Cantet (2008) 24. Mother by Bong Joon-ho (2009) 25. Shutter Island by Martin Scorsese (2010) 26. The Tree of Life by Terrence Malick (2011) 27. The Artist by Michel Hazanavicius (2011) 28. Melancholia by Lars von Trier (2011) 29. Hugo by Martin Scorsese (2011) 30. Twice Born by Sergio Castellitto (2012) 31. August Osage county by John Wells (2013) 32. 12 Years a Slave by Steve McQueen (2013) 33. The Best Offer by Giuseppe Tornatore (2013) 34. -

Climates a Film by Nuri Bilge Ceylan

WINNER FIPRESCI PRIZE IN COMPETITION 2006 Cannes Film Festival climates a film by Nuri Bilge Ceylan A Zeitgeist Films Release climates a film by Nuri Bilge Ceylan Winner of the prestigious Fipresci Award at the 2006 Cannes Film Festival, CLIMATES is internationally acclaimed writer-director Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s sublime follow-up to his Cannes multi-award winner DISTANT. Beautifully drawn and meticulously observed, the film vividly recalls the cinema of Italian master Michelangelo Antonioni with its poetic use of landscape and the incisive, exquisitely visual rendering of loneliness, loss and the often-elusive nature of happiness. During a sweltering summer vacation on the Aegean coast, the relationship between middle-aged professor Isa (played by Ceylan himself ) and his younger, television producer girlfriend Bahar (the luminous Ebru Ceylan, Ceylan’s real-life wife) brutally implodes. Back in Istanbul that fall, Isa rekindles a torrid affair with a previous lover. But when he learns that Bahar has left the city for a job in the snowy East, he follows her there to win her back. Boasting subtly powerful performances, heart-stoppingly stunning cinematography (Ceylan’s first work in high definition) and densely textured sound design, CLIMATES is the Turkish filmmaker’s most gorgeous rumination yet on the fragility and complexity of human relationships. BIOGRAPHIES Nuri Bilge Ceylan (Isa / Director-Screenwriter) Since winning the Grand Prize at Cannes in 2003 for DISTANT (Uzak), Nuri Bilge Ceylan, the ‘Lone Wolf ’ of Turkish cinema, has been critically acclaimed for his spare and unaffected style of filmmaking, inviting comparisons to Tarkovsky, Bresson and Kiarostami. Humorous and masterful, his is a cinema that spans the modern experi- ence: examining rural life, relationships, masculinity, and urban alienation. -

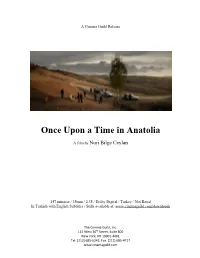

Once Upon a Time in Anatolia

A Cinema Guild Release Once Upon a Time in Anatolia A film by Nuri Bilge Ceylan 157 minutes / 35mm / 2.35 / Dolby Digital / Turkey / Not Rated In Turkish with English Subtitles / Stills available at: www.cinemaguild.com/downloads The Cinema Guild, Inc. 115 West 30th Street, Suite 800 New York, NY 10001‐4061 Tel: (212) 685‐6242, Fax: (212) 685‐4717 www.cinemaguild.com Once Upon a Time in Anatolia Synopsis Late one night, an array of men- a police commissioner, a prosecutor, a doctor, a murder suspect and others- pack themselves into three cars and drive through the endless Anatolian country side, searching for a body across serpentine roads and rolling hills. The suspect claims he was drunk and can’t quite remember where the body was buried; field after field, they dig but discover only dirt. As the night draws on, tensions escalate, and individual stories slowly emerge from the weary small talk of the men. Nothing here is simple, and when the body is found, the real questions begin. At once epic and intimate, Ceylan’s latest explores the twisted web of truth, and the occasional kindness of lies. About the Film Once Upon a Time in Anatolia was the recipient of the Grand Prix at the Cannes film festival in 2011. It was an official selection of New York Film Festival and the Toronto International Film Festival. Once Upon a Time in Anatolia Biography: Born in Bakırköy, Istanbul on 26 January 1959, Nuri Bilge Ceylan spent his childhood in Yenice, his father's hometown in the North Aegean province of Çanakkale. -

Türk Sinema Tarihi

TÜRK SİNEMA TARİHİ RADYO TELEVİZYON VE SİNEMA BÖLÜMÜ DOÇ. DR. ŞÜKRÜ SİM İSTANBUL ÜNİVERSİTESİ AÇIK VE UZAKTAN EĞİTİM FAKÜLTESİ Yazar Notu Elinizdeki bu eser, İstanbul Üniversitesi Açık ve Uzaktan Eğitim Fakültesi’nde okutulmak için hazırlanmış bir ders notu niteliğindedir. İÇİNDEKİLER 1. SİNEMANIN TÜRKİYE'YE GELİŞİ VE TÜRKİYE'DE YAPILAN İLK FİLMLER ..................................................................................................................... 3 2. SİNEMACILAR DÖNEMİ-2(1950-1970) ......................................................... 27 3. SİNEMACILAR DÖNEMİ(1950-1970) ............................................................ 53 4. KARŞITLIKLAR DÖNEMİ(1970-1980) .......................................................... 78 5. HAFTA DERS NOTU ........................................................................................... 98 6. VİZE ÖNCESİ GENEL DEĞERLENDİRME ................................................. 117 7. VİZE ÖNCESİ TEKRAR ................................................................................. 143 8. 1980 DÖNEMİ TÜRK SİNEMASI(1980-1990) .............................................. 158 9. 1980 DÖNEMİ TÜRK SİNEMASI(1980-1990) .............................................. 175 10. YENİ DÖNEM TÜRKİYE SİNEMASI ............................................................ 191 11. TÜRK SİNEMASINDA SANSÜR ................................................................... 201 12. MİLLİ SİNEMA ............................................................................................... -

New Turkish Cinema – Some Remarks on the Homesickness of the Turkish Soul

New Turkish Cinema – Some Remarks on the Homesickness of the Turkish Soul Agnieszka Ayşen KAIM, University of Lodz, [email protected] Abstract Contemporary cinematography reflects the dualism in modern Turkish society. The heart of every inhabitant of Anatolia is dominated by homesickness for his little homeland. This overpowering feeling affects common people migrating in search of work as well as intellectuals for whom Istanbul is a place for their artistic development but not the place of origin. The city and “the rest” have been considered in opposition to each other. The struggle between “the provincial” and “the urban” has even created its own film genre in Turkish cinematography described as “homeland movies”. They paint the portrait of a Turkish middle class intellectual on the horns of a dilemma, the search for a modern identity and a place to belong in a modern world where values are constantly shifting. Special Issue: 1 (2011) | ISSN 2158-8724 (online) | DOI 10.5195/cinej.2011.23 | http://cinej.pitt.edu This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License. This journal is published by the University Library System of the University of Pittsburgh as part of its D-Scribe Digital Publishing Program and is cosponsored by the University of Pittsburgh Press. New Turkish Cinema – Some Remarks on the Homesickness of the Turkish Soul For decades „It„s like a Turkish film” has been an expression with negative associations, being synonymous with kitch and banal. Over the last 10 years, Turkish cinematography has become recognised as the “New cinema of Turkey” thanks to appearances in festivals in Rotterdam, Linz, New York and Wrocław, Poland (“Era New Horizons”, 2010).