The Hudson River Valley Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT 2017 MISSION Boscobel House and Gardens preserves and shares the extraordinary beauty and historical significance of its Neoclassical mansion, renowned collection of early 19th-century decorative arts, and iconic Hudson River landscape. Boscobel embodies the Hudson Valley’s ongoing, dynamic exchange between design, history, and nature; and engages growing, diverse audiences in that conversation. VISION Boscobel inspires and informs visitors—from children and their families to subject specialists—through active and meaningful experiences of design, history, and nature. BOARD OF DIRECTORS, Summer 2018 STAFF, Summer 2018 Barnabas McHenry, President Jennifer Carlquist, Executive Director Elizabeth Gunther, Visitor Services / Alexander Reese, Vice President Design Shop Associate Linda Alfano, Events Assistant / Gardener Arnold Moss, Secretary and Treasurer Dana Hammond, Development Manager Deanna Argenio, Museum Guide Frances Hodes, Museum Guide William J. Burback JoAnn Bellia, Museum Guide Marie Horkan, Museum Guide Gilman S. Burke, Esq. Kendall Bland, Security Guard Stephen Hutcheson,Museum Guide Henry N. Christensen, Jr. Gunta Broderick, Bookkeeper Samuel Lawson, Jr., Museum Guide Susan Davidson Cliff Bowen, Maintenance Technician Emily Lombardo, Museum Guide Meg Downey Kathleen Burke, Museum Guide Jessica Lynn, Visitor Services / Robert G. Goelet Kasey Calnan, Collections Assistant / Design Shop Associate Col. James M. Johnson Design Shop Associate Harold MacAvery, Maintenance Technician Peter M. Kenny Elizabeth Chirico, Visitor -

WORFIELD in the SEVENTEENTH CENTURY (PART 2) This Article Is

WORFIELD IN THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY (PART 2) This article is not specifically linked to Worfield but since the events described were of such national importance, happened so locally and must have involved the parish, I hope you will forgive this diversion. There is another reason for telling this story – it is a fantastic tale and who better to tell it than a parishioner who is a descendant of one of the key families involved The first English Civil War ended in 1646. King Charles 1 surrendered to the Scots but unfortunately for Charles the Scots made a deal with Parliament and the King was handed over to Parliament. In 1648 there was a second Civil War organised by the King from his prison on the Isle of Wight. This was soon put down by Oliver Cromwell. King Charles 1 was beheaded on 30th January 1649 for treason. The treasonable offence was waging war on his own people. England became a republic and was ruled as a Commonwealth by Oliver Cromwell until his death in 1658. There was a third Civil War in 1651 when King Charles 11 attempted to regain the throne, with the help of the Scots. The war began and ended with Charles' defeat at the Battle of Worcester on 3rd September 1651 and that is where this story begins. Charles was a brave soldier and reluctant to admit defeat. He urged his followers to fight, even as they were throwing down their arms. He rode up and down among them, shouting, “I had rather you would shoot me, than keep me alive to see the sad consequences of this fateful day.” But it was a lost cause. -

Oakwood House, 16, Old Coach Road, Bishops Wood, Stafford, Staffordshire, ST19 9AD Asking Price £650,000

EPC E Oakwood House, 16, Old Coach Road, Bishops Wood, Stafford, Staffordshire, ST19 9AD Asking Price £650,000 **EXTENSIVE FAMILY HOME, ** VERSATILE FAMILY HOME, ** IN AND OUT DRIVEWAY, ** LARGE PLOT, ** VILLAGE LOCATION,*( Oakwood House is located in the popular village of Bishops Wood, It is home to the Royal Oak public house, the first to be named after the nearby oak tree at Boscobel House in which King Charles II hid after the Battle of Worcester. Comuter links include within easy reach of major roads such as A5, M6 & M6 Toll. On entering the village of Bishops Wood from the A5 Watling Street, take the first left hand turning signposted Brewood and the property is located on the right hand side. Do you need a home that will cater for your ever growing family from their first steps in life right through to when your brood fly the nest -Lots of space is on offer at Oakwood House therefore viewing is recommended early to appreciate what this home offers. The home offers spacious and versatile accommodation and comprises of Entrance Hall, Large Lounge, Dining Room, Further Reception Room/ Snug, Breakfast Kitchen, Utility Room, Downstairs WC, Six good size Bedrooms, En-suite to Master, Family Bathroom. Externally the property boasts in and out driveway leading to garage and a private enclosed garden. Glorious views overlooking fields makes waking up easier. Viewing is essential to appreciate. Viewing arrangement by appointment 01543 503678 [email protected] Bairstow Eves, 13 Wolverhampton Road, Cannock, WS11 1AP https://www.bairstoweves.co.uk Interested parties should satisfy themselves, by inspection or otherwise as to the accuracy of the description given and any floor plans shown in these property details. -

An Evolved Understanding: an Examination of the National

AN EVOLVED UNDERSTANDING: AN EXAMINATION OF THE NATIONAL PARK SERVICE’S APPROACH TO THE CULTURAL LANDSCAPE AT CHATHAM MANOR, FREDERICKSBURG AND SPOTSYLVANIA NATIONAL MILITARY PARK A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Olivia Holly Heckendorf August 2019 © 2019 Olivia Holly Heckendorf ii ABSTRACT Chatham Manor became part of the Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park in December 1975 after the death of its last private owner, John Lee Pratt. Constructed between 1768 and 1771, Chatham Manor has always been intertwined with the landscape and has gained significance throughout its 250-year lifespan. With each subsequent owner and period of time Chatham Manor has gained significance as a cultural landscape. Since its acquisition in 1975, the National Park Service has grappled with the significance and interpretation of Chatham Manor as a cultural landscape. This thesis provides an analysis of the National Park Service’s ideas of significance and interpretation of the cultural landscape at Chatham Manor. This is done through a discussion of several interpretive planning documents and correspondences from the staff of the National Park Service, including interpretive prospectuses, a general management plan, and long-range interpretive plan. In addition, the influence of both superintendents and staff is taken into consideration. Through the analysis of these documents, it was realized that the understanding of cultural landscapes is continuing to evolve within the National Park Service. In the 1960s and 1970s Chatham Manor was considered significant and interpreted almost solely for its association with the Civil War. -

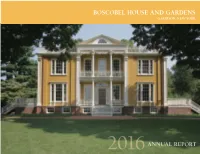

To Open the 2016 Report

BOSCOBEL HOUSE AND GARDENS GARRISON, NEW YORK 2016 ANNUAL REPORT Boscobel Mission Statement Board of Directors, Spring 2017 Barnabas McHenry, President Meg Downey The Mission of Boscobel House Alexander Reese, Vice President Robert G. Goelet and Gardens is to enrich the lives Arnold Moss, Secretary Col. James M. Johnson Col. Williams L. Harrison Jr., Treasurer Peter Kenny of its visitors with memorable John S. Bliss Frederick H. Osborn, III experiences of the history, culture William J. Burback Susan Hand Patterson and environment of the Hudson Gilman S. Burke McKelden Smith Henry N. Christensen, Jr. Margaret Tobin River Valley. Susan Davidson Denise Doring VanBuren Boscobel Brand Idea Staff Steven Miller, Executive Director Joseph Gocha, Maintenance The past shapes who we are Linda Alfano, Maintenance Patrick Griffin,Docen t today – our culture, our style, JoAnn Bellia, Docent Edward Griffiths,Security Kendall Bland, Security Liz Gunther, Visitor Services our values and our traditions. Chloe Blaney, Gift Shop Frances Hodes, Docent The history of the Early Republic Donna Blaney, Marketing & Events Manager Marie Horkan, Docent Cliff Bowen, Maintenance Stephen Hutcheson, Docent is woven into the fabric of our Gunta Broderick, Bookkeeper Samuel Lawson, Docent society. It lives on through stories Kathy Burke, Docent Emily Lombardo, Docent Kasey Calnan, Gift Shop John Malone, Facilities Manager and experiences here. Boscobel’s Jennifer Carlquist, Curator Harold MacAvery, Maintenance extraordinary location in the Russel Cox, Maintenance Carolyn McShea, Development Assistant Hudson River Valley offers an Betty Chirico, Visitor Services Linda Moore, Visitor Services Lisa DiMarzo, Museum Educator Mary Nolan, Gift Shop immersive window into our past, Renee Edelman, Docent Dorothy Scheno, Docent bringing it to life to enrich and Colleen Fogarty, Property Rental Manager Charles Shay, Docent Maria Gaffney, Gift Shop Renate Smoller, Gift Shop Manager delight our visitors in a way that Edward Glisson, Visitor Services Manager Pat Turner, Housekeeping is relevant today. -

Boscobel House Garden Volunteer Role Description

Boscobel House Garden Volunteer Role Description Why does English Heritage need my support? Boscobel House and its Royal Oak tree became famous as hiding places of King Charles II after his defeat at the Battle of Worcester in 1651. After Charles’s visit Boscobel remained a working farm, and today you can visit the lodge, farmyard, gardens and a descendant of The Royal Oak. The gardens at Boscobel House provide a beautiful setting for a variety of garden work and with our plans to develop the gardens in 2019 and 2020, now is a great time to get involved. Where will I be based? Boscobel House, Brewood, Staffordshire ST19 9AR. There’s also opportunity to join the teams at other local sites including Stokesay Castle and Wenlock Priory. What will I be doing? As a member of the gardens team you’ll help maintain and develop the gardens of Boscobel House and as such you will need to: Participate in a broad range of horticultural activities including weeding, propagation, planting and re-potting Answer questions from visitors and offer information where appropriate regarding the garden and its history Take instruction from the garden staff and be able to work independently or as part of a team. For security purposes you will also need to: Understand and implement safety procedures including evacuation Maintain a level of visitor supervision in the garden. How much time will I be expected to give? Sessions are on Tuesdays from 10.00am to 3.00pm. We hope that you’ll be able to join us weekly but this flexible. -

The Hudson River Valley Review

THE HUDSON RIVER VA LLEY REVIEW A Journal of Regional Studies The Hudson River Valley Institute at Marist College is supported by a major grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Publisher Thomas S. Wermuth, Vice President for Academic Affairs, Marist College Editors Christopher Pryslopski, Program Director, Hudson River Valley Institute, Marist College Reed Sparling, Writer, Scenic Hudson Editorial Board The Hudson River Valley Review Myra Young Armstead, Professor of History, (ISSN 1546-3486) is published twice Bard College a year by The Hudson River Valley BG (Ret) Lance Betros, Provost, U.S. Army War Institute at Marist College. College Executive Director Kim Bridgford, Founder and Director, Poetry by James M. Johnson, the Sea Conference, West Chester University The Dr. Frank T. Bumpus Chair in Michael Groth, Professor of History, Frances Hudson River Valley History Tarlton Farenthold Presidential Professor, Research Assistant Wells College Erin Kane Susan Ingalls Lewis, Associate Professor of History, Megan Kennedy State University of New York at New Paltz Emily Hope Lombardo Tom Lewis, Professor of English, Skidmore College Hudson River Valley Institute Advisory Board Sarah Olson, Superintendent, Alex Reese, Chair Roosevelt-Vanderbilt National Historic Sites Barnabas McHenry, Vice Chair Roger Panetta, Visiting Professor of History, Peter Bienstock Fordham University Margaret R. Brinckerhoff H. Daniel Peck, Professor of English Emeritus, Dr. Frank T. Bumpus Vassar College Frank J. Doherty BG (Ret) Patrick J. Garvey Robyn L. Rosen, Professor of History, Shirley M. Handel Marist College Maureen Kangas David P. Schuyler, Arthur and Katherine Shadek Mary Etta Schneider Professor of Humanities and American Studies, Gayle Jane Tallardy Franklin & Marshall College Denise Doring VanBuren COL Ty Seidule, Professor and Head, Department Business Manager of History, U.S. -

Boscobel Or, the Royal Oak

Boscobel or, the Royal Oak William Harrison Ainsworth Boscobel or, the Royal Oak Table of Contents Boscobel or, the Royal Oak......................................................................................................................................1 William Harrison Ainsworth..........................................................................................................................1 Book the first: the Battle of Worcester.......................................................................................................................4 Chapter 1. HOW CHARLES THE SECOND ARRIVED BEFORE WORCESTER, AND CAPTURED A FORT, WHICH HE NAMED FORT ROYAL ..............................................................4 Chapter 2. SHOWING HOW THE MAYOR OF WORCESTER AND THE SHERIFF WERE TAKEN TO UPTON−ON−SEVERN, AND HOW THEY GOT BACK AGAIN.....................................10 Chapter 3. HOW CHARLES MADE HIS TRIUMPHAL ENTRY INTO WORCESTER; AND HOW HE WAS PROCLAIMED BY THE MAYOR AND SHERIFF OF THAT LOYAL CITY......................14 Chapter 4. HOW CHARLES WAS LODGED IN THE EPISCOPAL PALACE; AND HOW DOCTOR CROSBY PREACHED BEFORE HIS MAJESTY IN THE CATHEDRAL...........................17 Chapter 5. HOW CHARLES RODE TO MADRESFIELD COURT; AND HOW MISTRESS JANE LANE AND HER BROTHER, WITH SIR CLEMENT FISHER, WERE PRESENTED TO HIS MAJESTY...................................................................................................................................................20 Chapter 6. HOW CHARLES ASCENDED THE WORCESTERSHIRE -

Site (Alphabetically)

Sites which are FREE TO VISIT for Corporate Members Opening times vary, pre-booking may be required, please check English Heritage website for details. Site (alphabetically) County 1066 Battle of Hastings, Abbey and Battlefield East Sussex Abbotsbury Abbey Remains Dorset Acton Burnell Castle Shropshire Aldborough Roman Site North Yorkshire Alexander Keiller Museum Wiltshire Ambleside Roman Fort Cumbria Appuldurcombe House Isle of Wight Apsley House London Arthur's Stone Herefordshire Ashby de la Zouch Castle Leicestershire Auckland Castle Deer House Durham Audley End House and Gardens Essex Avebury Wiltshire Aydon Castle Northumberland Baconsthorpe Castle Norfolk Ballowall Barrow Cornwall Banks East Turret Cumbria Bant's Carn Burial Chamber and Halangy Isles of Scilly Barnard Castle Durham d's Cove Fort Devon Bayham Old Abbey Kent Beeston Castle Cheshire Belas Knap Long Barrow Gloucestershire Belsay Hall, Castle and Gardens Northumberland Benwell Roman Temple and Vallum Crossing Tyne and Wear Berkhamsted Castle Hertfordshire Berney Arms Windmill Hertfordshire Berry Pomeroy Castle Devon Berwick-upon-Tweed Castle, Barracks and Main Guard Northumberland Binham Market Cross Norfolk Binham Priory Norfolk Birdoswald Roman Fort Cumbria Bishop Waltham Palace Hampshire Black Carts Turret Northumberland Black Middens Bastle House Northumberland Blackbury Camp Devon Blackfriars, Gloucester Gloucestershire Blakeney Guildhall Norfolk Bolingbroke Castle Lincolnshire Bolsover Castle Derbyshire Bolsover Cundy House Derbyshire 1 Boscobel House and The -

Boscobel House and the Royal Oak Teachers'

KS1-2KS1–2 KS3 TEACHERS’ KIT KS4 Boscobel House and the Royal Oak SEND This kit helps teachers plan a visit to Boscobel House and the Royal Oak. Boscobel played a brief but important role in the English Civil War when it sheltered and hid the future King Charles II. Use these resources before, during and after your visit to help students get the most out of their learning. GET IN TOUCH WITH OUR EDUCATION BOOKINGS TEAM: 0370 333 0606 [email protected] bookings.english-heritage.org.uk/education Share your visit with us on Twitter @EHEducation The English Heritage Trust is a charity, no. 1140351, and a company, no. 07447221, registered in England. All images are copyright of English Heritage or Historic England unless otherwise stated. Published March 2021 WELCOME This Teachers’ Kit for Boscobel House and the Royal Oak has been designed for teachers and group leaders to support a free self-led visit to the site. It includes a variety of materials suited to teaching a wide range of subjects and key stages, with practical information, activities for use on site and ideas to support follow-up learning. We know that each class and study group is different, so we have collated our resources into one kit allowing you to decide which materials are best suited to your needs. Please use the contents page, which has been colour- coded to help you easily locate what you need and view individual sections. All of our activities have clear guidance on the intended use for study so you can adapt them for your desired learning outcomes. -

Former Beacon Mayor Joins Incline Society Board of Trustees

For Immediate Release Contact: Mike Colarusso Date: April 26, 2010 Chief Operating Officer PR #: 2010-003 Tel: (845) 765-3262 x17 [email protected] http://www.inclinerailway.org http://www.facebook.com/inclinerailway Former Beacon Mayor Joins Incline Society Board of Trustees (Beacon, NY) – The Mount Beacon Incline Restoration Society has rapidly grown in capability and professionalism over the last year. Now former Beacon Mayor Clara Lou Gould has joined the Society’s Board of Trustees. She takes her place alongside several other prominent figures, to include Beacon Mayor Steve Gold, Town of Fishkill Supervisor Joan Pagones, and Walkway Chairman Fred Schaeffer. When asked why she accepted the board’s membership invitation, Gould responded that “Beacon is in such a beautiful area that one of my hardest decisions is which is more beautiful - to be up on the mountain looking down at the river or out on the river looking up at the mountain. The return of the Mount Beacon Incline Railway will make it possible for many more people to puzzle over that -- while enjoying the spectacular views.” A native of the Hudson Valley, Gould was born in Cold Spring, New York. She later moved to Beacon and was sworn in as the city’s first woman mayor in 1990. During her 18 years in office, she worked to have Beacon designated one of the initial model communities of the Hudson River Valley Greenway. Under her leadership, the city was also winner of the inaugural Hudson Valley Quality Community Award and was designated a Preserve America Community. She saved from development a 100-plus acre property at the base of Fishkill Ridge and collaborated with Scenic Hudson to create a park at the 80-acre former University Settlement Camp. -

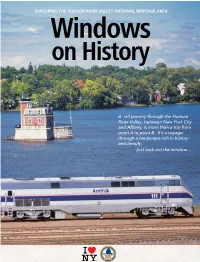

Windows on History

EXPLORING THE HUDSON RIVER VALLEY NATIONAL HERITAGE AREA Windows on History A rail journey through the Hudson River Valley, between New York City and Albany, is more than a trip from point A to point B. It’s a voyage through a landscape rich in history and beauty. Just look out the window… Na lley tion Va al r H e e v r i i t R a g n e o A s r d e u a H Na lley tion Va al r H e e v r i i t R a g n e o A s r d e u a H W ELCOME TO THE HUDSON RIVER VALLEY! RAVELING THROUGH THIS HISTORIC REGION, you will discover the people, places, and events that formed our national identity, and led Congress to designate the Hudson River Valley as a National Heritage Area in 1996. The Hudson River has also been designated one of our country’s Great American Rivers. TAs you journey between New York’s Pennsylvania station and the Albany- Rensselaer station, this guide will interpret the sites and features that you see out your train window, including historic sites that span three centuries of our nation’s history. You will also learn about the communities and cultural resources that are located only a short journey from the various This project was made station stops. possible through a partnership between the We invite you to explore the four million acres Hudson River Valley that make up the Hudson Valley and discover its National Heritage Area rich scenic, historic, cultural, and recreational and I Love NY.