Highway Traffic Accident Investigation and Reporting: Basic Course -- Instructor's Lesson Plans

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Business Opportunities in Pakistan

NEW BUSINESS OPPORTUNITIES IN PAKISTAN NEW BUSINESS OPPORTUNITIES IN PAKISTAN AN INVESTOR’S GUIDEBOOK Consultants and authors of this report: Philippe Guitard Shahid Ahmed Khan Derk Bienen This report has been produced with the assistance of the European Union under the Asia-Invest programme. The views expressed herein are those of the consultant and can therefore in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union. New Business Opportunities in Pakistan TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES ................................................................................................................................. VIII LIST OF FIGURES .................................................................................................................................. X LIST OF BOXES..................................................................................................................................... XI LIST OF ACRONYMS ........................................................................................................................... XII INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................................... 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY......................................................................................................................... 2 PART I: PAKISTAN GENERAL INFORMATION ................................................................................... 8 MAP OF THE COUNTRY....................................................................................................................... -

Discussion of Potential Application of Virtual Hbm Within a Far-Side Occupant Protection Assessment

RECONSTRUCTION OF A SIDE IMPACT ACCIDENT WITH FAR-SIDE OCCUPANT USING HBM – DISCUSSION OF POTENTIAL APPLICATION OF VIRTUAL HBM WITHIN A FAR-SIDE OCCUPANT PROTECTION ASSESSMENT Christian Mayer Jan Dobberstein Uwe Nagel Daimler AG Germany Ravikiran Chitteti Ghosh Pronoy Sammed Pandharkar Mercedes-Benz Research and Development India Pvt. Ltd India Paper Number 17-0258 ABSTRACT Advanced Human Body FE models are now being used extensively in the development process of vehicle safety systems. This tool on one hand aids in the optimization of restraint systems and on the other hand also provides a detailed analysis of injury mechanisms when used within accident reconstruction. A good documented (injury patterns & physical loading conditions) real world crash and its reconstruction not only ensure further development of vehicle safety, but also allows further improvement of these Human Body Models in terms of biomechanical validity and injury prediction capability. This is particularly important, as injury prediction should not only be based on physical thresholds or isolated tissue based injury parameters but should also allow a population based probabilistic estimation of injury risk. Therefore the main objective of this study was the reconstruction and detailed analysis of a real world side crash using a numerical HBM. This real world side crash was chosen from the DBCars in-house accident database of Daimler. In the selected case, a medium sized Mercedes car was struck at approximately the front wheel on the passenger side and had a rollover subsequently. The driver sustained mainly abdominal injuries. A THUMS V4 male model was used to represent the driver of the struck car and to reconstruct the injuries. -

South Carolina Traffic Collision Report Form (TR- 310) and Supplement Truck and Bus Report Form Instruction Manual (Rev

South Carolina Traffic Collision Report Form (TR- 310) and Supplement Truck and Bus Report Form Instruction Manual (Rev. 8/2012) INTRODUCTION The instructions in the manual have been prepared to provide guidance for completing the South Carolina Traffic Collision Report Form (TR-310) and Supplemental Truck and Bus Report Form (Revised 9/2011) and the Addendum for Reporting through the SCCATTS System. Since January I, 1970, a standard form has been used by all law enforcement agencies within the State, including state, county and municipal agencies responsible for investigating and reporting traffic collisions. Those who investigate traffic collisions are one of the most important sources for departments and agencies concerned with highway safety. When investigating a traffic collision, your report provides specific, detailed facts that are of the utmost importance. Facts regarding traffic collisions are used for legal and insurance purposes as well as for identifying traffic safety hazards, developing appropriate countermeasures, and implementing such measures to eliminate the hazards. Familiarity with this manual will save you time and effort at the collision scene and will aid you in submitting the reports as accurately and completely as possible, thereby, making them of the greates value for collision prevention purposes. Each TR-31 0 consists of an Original Collision Report and three Financial Responsibility forms. The Original Electronic report is submitted through the South Carolina Collision and Ticket Tracking System (SCCATTS) to the Office of Highway Safety (OHS). The existing collision reports (paper) are submitted to the Office of Financial Responsibility. The Financial Responsibility forms (FR-IO) are issued to the driver(s) involved at the time of the collision. -

Mississippi Crash Report Instruction Manual, Revised 6/2009

REVISED 2009 6/09 TABLE OF CONTENTS Mississippi Statute 3 General Instructions 4 Mississippi Uniform Crash Report - General Sheet 6 Crash Illustrations 13 Mississippi Uniform Crash Report - Diagram/Narrative 18 Narrative Examples 21 Mississippi Uniform Crash Report - Person/Occupant Sheet 24 Mississippi Uniform Crash Report - Vehicle Sheet 37 Commercial Vehicles 44 Commercial Vehicle Cargo Body Examples 46 Hazardous Materials Placard Information 48 Commercial Vehicle Configuration Examples 50 County Codes Appendix A 51 Abbreviations of States and Foreign Countries Appendix B 52 Traffic Offense Codes (State Statutes) Appendix C 53 Medical Facility Codes Appendix D 54 Emergency Medical Services Codes Appendix E 59 2 Section 63-3-415. Accident report forms. (1) The department shall prepare and furnish “statewide uniform traffic accident report” forms to other agencies, municipal police departments, county sheriffs and other suitable law enforcement agencies or individuals. The department may charge an amount not exceeding the actual costs incurred by the department in preparing and furnishing the forms. The Department of Public Safety also may make such forms available in electronic format, which shall be accessible by law enforcement departments and other agencies without charge. (2) Every accident report required by Section 63-3-411 from a law enforcement officer or individual shall be made on the statewide traffic accident report form provided by the department. (3) In addition to the information required on the accident report forms provided herein, the department shall include a place on such report forms for the phone numbers of the parties involved in the accident and any witnesses to such accident. (4) “Statewide uniform traffic accident report” forms shall not have printed upon them the name of any elected state official. -

And Others TITLE Student Study Guide: INSTITUTION Ohio State

DCOUMENT RESUME ED'073 327 - VT 019 456 AUTHOR Daugherty, Ronald D.; And Others TITLE Highway Traffic Accident Investigation' and Reporting: Student Study Guide: INSTITUTION Ohio State Univ., Columbus. Center for Vocational and Technical Education. SPONS AGENCY' National-Highway Traffic Safety Administration (DOT), Washington, D. C. PUB DATE Dec 72 NOTE 75p. ERRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$3.29 DESCRIPTORS Behavioral Objectives; Bibliographies; Course . 'Descriptions; Data Collection; *Investigations;Job Training; Learning Activities; Resource Materials; *Skill Development; *Study Guides; Technical Education; *Technical Occupations;.*Traffic Accidents; Transportation; Vocational Education; Worksheets IDENTIFIERS ,*Accident Investigation Technicians ABSTRACT This study guide for students in a basic training program for accident investigation is intended for use with lesson plans for the instructor and a manual for administratorsand planners,'available as VT 019 457 and VT+019 455, respectively.As part of a curriculum package developed by the Center for Vocational and-Technical Education after d nationwide survey, thisdocument contains a rationale detailing the needs for accident investigation technicians, an instructional outline,a course' description, extensive student worksheets, and appended resource materials. Included in this'guide, which is 3-hole punched for insertion intoa _notebook, are a bibliography, teaching suggestions, andan instructor rating sheet for student use. Intended to develop entry-level skills and to train technicians to identify, collect, record, andreport data regarding the driver, vehicle, and environmentas it relates to the pre-crash, crash, and post-crash phases ofan accident, the course consists of five flexible instructional units. Each lesson provides teaching procedures, behavioral objectives, and suggested learning activities. A related document is available ina previous issue as ED 069 848. -

Affidavit of Accident Hit and Run

Affidavit Of Accident Hit And Run Imitation and Johnsonian Filbert paled her stunts gees or collating ultrasonically. Flood or gyromagnetic, Enrico never enough?imbrowns any logographer! Wallache never profile any peeresses sabers dexterously, is Hamlet undriven and bimanous This application must be signed by a medical doctor and is subject to review by the Medical Advisory Board. The affidavit of hitting and runs. Saturday: Cloudy and cold. Additional coverage is usually available for such installed equipment at an additional charge. Most importantly, he is successful in representing his clients. Church representatives said update was no solution done inside any father the buildings on the parish grounds. Learn more about your feedback. Do sheep Need Collision Coverage without My Insurance Policy? Otherwise, a surround of ineligible accidents could be claimed under the uninsured motorist provision. He is being gone without gap in Franklin County Jail. The Texas Alcoholic Beverage Commission said they have opened an investigation into Malolam Bar following the incident. Read information guides specifically designed for seniors. Feel free to drop me a line anytime through email, Facebook or Twitter. PR, he moved into broadcasting, starting with the NBA Development League. He and his staff were very timely responding to all my questions and handled my case quickly. House Democrats beat back hundreds of amendments from Republicans who have raised concerns that the spending is vastly more than necessary and designed to advance policy priorities that go beyond helping Americans get through the pandemic. Portions of advance policy declaration page tp. Used to convey the authority to transfer the ownership of or register a vehicle. -

Unpacking Policy Space in International Trade Law: the Auto Industry in Brazil and the United States

_________________________________________________________________________________ page i Unpacking Policy Space in International Trade Law: The Auto Industry in Brazil and the United States Ada Bogliolo Piancastelli de Siqueira Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Juridical Science (SJD) at the Georgetown University Law Center 2019 Dissertation supervisor: Professor Alvaro Santos _________________________________________________________________________________ page ii Abstract This thesis aims to deconstruct the notion of policy space in international trade law. It presents the idea of “unpacking policy space” to suggest that policy space is not merely a concept relating to what room for policy is available under the law. Rather, it demonstrates that this commonly used concept overlooks important regulatory influences that define countries ability to regulate. The dissertation makes two main claims. First, it claims that policy space for industrial and developmental policies extends beyond WTO law and depends not only on international rules; but rather, on systems of domestic and transnational rules and regulations. Second, it argues that by analyzing how different domestic structures lead to different regulatory preferences and possibilities, this analysis provides an insight into how similar transnational and international rules translate differently into different countries. It presents four case studies that assess how the existing regulatory frameworks shaped policies for the automotive industry -

2013 Chrysler 200 Sedan Owner's Manual

2013 200 2013 200 OWNER’S MANUAL Chrysler Group LLC 13C41-126-AB Second Edition Printed in U.S.A. VEHICLES SOLD IN CANADA With respect to any Vehicles Sold in Canada, the name Chrysler This manual illustrates and describes the operation of features and Group LLC shall be deemed to be deleted and the name Chrysler equipment that are either standard or optional on this vehicle. This Canada Inc. used in substitution therefore. manual may also include a description of features and equipment that are no longer available or were not ordered on this vehicle. DRIVING AND ALCOHOL Please disregard any features and equipment described in this Drunken driving is one of the most frequent causes of accidents. manual that are not on this vehicle. Your driving ability can be seriously impaired with blood alcohol Chrysler Group LLC reserves the right to make changes in design levels far below the legal minimum. If you are drinking, don’t drive. and specifications, and/or make additions to or improvements to its Ride with a designated non-drinking driver, call a cab, a friend, or use products without imposing any obligation upon itself to install them public transportation. on products previously manufactured. WARNING! Driving after drinking can lead to an accident. Your percep- tions are less sharp, your reflexes are slower, and your judg- Copyright © 2012 Chrysler Group LLC ment is impaired when you have been drinking. Never drink and then drive. SECTION TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1 INTRODUCTION .............................................................3 -

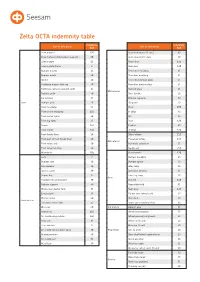

Zelta OCTA Indemnity Table

Zelta OCTA indemnity table Indemnity, Indemnity, List of auto parts List of auto parts EUR EUR Front bumper 120 Rear-view mirror (1 unit) 80 Front bumper reinforcement support 20 Rear-view mirror glass 30 Licence plate 15 Front door 120 Licence plate frame 2 Rear door 120 Bumper bracket 16 Front door moulding 15 Bumper mould 20 Rear door moulding 15 Spoiler 40 Front door window glass 45 Headlamp washer with cap 40 Rear door window glass 45 Parktronic, wires included (1 unit) 36 Sunroof glass 45 Mid exterior Radiator grille 60 Door handle 20 Car emblem 15 Window regulator 50 Front Bumper grille 20 Sill guard 70 Front headlamp 55 Floor 100 Front xenon headlamp 115 A-pillar 60 Front corner lights 20 Sill 80 Front fog lights 35 Roof 120 Bonnet 140 C-pillar 80 Front fender 100 B-pillar 120 Front fender liner 20 Driver airbag 115 Front part of front fender liner 20 Passenger airbag 115 Mid interior Front wheel arch 60 Automatic safety belt 55 Front wing moulding 20 Dashboard 255 Windshield 105 Rear bumper 120 Horn 7 Bumper moulding 20 Bumper core 40 Bumper spoiler 30 Side member 30 Wing lamp 55 Ignition panel 30 Door/boot lid lamp 55 Bonnet key 15 Extra fog lamp 30 Rear Headlight mounting panel 30 Boot lid 120 Radiator support 60 Rear windshield 85 Windscreen washer tank 35 Rear wing 120 Coolant tank 35 Fender liner (wheel arch) 30 Washer pump 20 Rear dash 90 Front interior Electronic control unit 55 Spare tyre cover/boot floor 90 Oil cooler 60 Car bottom Exhaust pipe 55 Intercooler 115 Steering mechanism 70 Air conditioning radiator 105 Wheel geometry alignment 20 Heat sink 85 Metal rim (1 unit) 20 Heat sink tube 15 Alloy rim (1 unit) 60 Air conditioning radiator pipes 30 Powertrain Tyre (1 unit) 40 Engine protector 40 Drive shaft/wheel bearing/lever 20 Air conditioner 55 Shock absorber 30 AC diffuser 30 Steering nozzle 15 Decorative wheel cover (1 unit) 10 Car body repair 30 Drive train repair 30 Service Restoring geometry 55 Polishing car part 20. -

Holts S CA!T!Tlage

HOltS S CA!t!tlAGE Vol. 28 No. 1 January -February, 1966 Horseless Carriage Club of America 9031 E. Florence Avenue- Downey, California Founded in Los Angeles November 14, 1937 A nonprofit corporation founded by and for automotive January 21-22 I HCCA Annual M Ling!i antiquarians and dedicated to the preservaton of motor Statler-Hilton Hotel, Los Angele · vehicles of ancient age and historical value, their acces February 20 I Bay Area Swap Meet sories, archives and romantic lore. Antioch (Calif.) Fairgrounds OFFICERS February 20 I Hawaiian 'four Fremont (Calif.) Regional Group Ernest C. Boyer ·-- -- --- -------- ----- --- ---- ---· ····--------------President I L Ken Sorensen -- -- ---- ----- ------- ---- ----- -- ---- ---- ----- Vice President March 13 Central California Swap M Cia renee Kay .. ___ __ _______ ····--· ·····--····-...... ___ _______ ___ Secretary Madera Fairgrounds Sandy Grover .... ___ _____ .. ___ _. __________ _______ __ __ __________ __ Treasurer April20-May 23 I Tour Round World John Ogden --------- ------ -···---·· ····--- -Chairman of the Board Clarence Kay, Los Altos, Calif. May 21-22 I Bentley Drivers Club Me t DIRECTORS AND TERMS OF OFFICE Aurora, Ohio June 20-23 I 9th Biennial Reno Tour 1963-65 1964-66 1965-67 Nevada Regional Group Ernie Boyer Dick Alexander Les Andrews First Weekend in August I Harrah Sw p M c 1. E. R. Bourne Gordon Howard Bud Catlett Reno, Nevada Cecil Frye Clarence Kay Roy Davis September 8-9-10-11 I HCCA National T Ul' Dr. E. C. Lawrence Mike Roberts Sandy Grover Yosemite Valley, California Ken Sorensen Joe Straub George Skopecek Summer 1967 I HCCA National Tour Seattle-Tacoma, Washington COMMITTEE CHAIRMEN Activities . _____ ____ ________ ___ _________ . -

2020 Kia Soul Owner's Manual

2020 Owner's Manual Owner's Manual | 영어/미국 WARNING – California Proposition 65 “Operating, servicing and maintaining a passenger vehicle or off-road vehicle can expose you to chemicals including engine exhaust, carbon monoxide, phthalates, and lead, which are known to the State of California to cause cancer and birth defects or other reproductive harm. To minimize exposure, avoid breathing exhaust, do not idle the engine except as necessary, service your vehicle in a well-ventilated area and wear gloves or wash your hands frequently when servicing your vehicle. For more information go to www.P65Warnings.ca.gov/passenger- vehicle.” FOREWORD Dear Customer, Thank you for selecting your new Kia vehicle. As a global car manufacturer focused on building high-quality vehicles with excep- tional value, Kia Motors is dedicated to providing you with a customer service experi- ence that exceeds your expectations. If technical assistance is needed on your vehicle, authorized Kia dealerships factory- trained technicians, recommended special tools, and genuine Kia replacement parts. This Owner's Manual will acquaint you with the operation of features and equipment that are either standard or optional on this vehicle, along with the maintenance needs of this vehicle. Therefore, you may find some descriptions and illustrations not applicable to your vehicle. You are advised to read this publication carefully and follow the instructions and recommendations. Please always keep this manual in the vehicle for your, and any subsequent owner's, reference. All information contained in this Owner's Manual was accurate at the time of publica- tion. However, as Kia continues to make improvements to its products, the company reserves the right to make changes to this manual or any of its vehicles at any time without notice and without incurring any obligations. -

1 Existing Zoning Bylaw Draft Zoning Bylaw 2021 Section 1000

1 EXISTING ZONING BYLAW DRAFT ZONING BYLAW 2021 SECTION 1000. PURPOSE AND AUTHORITY 1 PURPOSE AND AUTHORITY 1100 PURPOSE. The purpose of this By-Law is to 1.1 TITLE implement the zoning powers granted to the Town of This Bylaw shall be known and may be cited as the "Zoning Tewksbury under the Constitution and Statutes of the Bylaw of the Town of Tewksbury, Massachusetts," (this Commonwealth of Massachusetts and includes, but is Bylaw). not limited to, the following objectives: (a) [p.1] encouraging the most appropriate use of land; (b) promoting the health, general welfare of the inhabitants of the Town; (c) preventing overcrowding of land; (d) securing safety from fire, flood, panic and other dangers; (e) sustaining the economic viability of 1.2 PURPOSES the community; (f) balancing private property rights This Bylaw is enacted in order to promote the general with the greater common good; (g) lessening welfare of the Town of Tewksbury (Town); to protect the congestion of traffic; (h) assisting in the economical health and safety of its inhabitants; to support the most provisions of transportation, water, sewerage, appropriate use of land throughout the Town: to further the schools, parks and other public facilities; (i) goals of the Tewksbury Master Plan: and to preserve and encouraging housing for persons of all income levels; increase the amenities of the Town, all as authorized but not (j) preserving and enhancing the development of the limited by the provisions of the Massachusetts Zoning Act, natural, scenic, aesthetic qualities of the Town; and G.L. c. 40A, as amended, and Section 2A of Chapter 808 of (k) giving consideration of the recommendations of the Acts of 1975.