Bird-Banding Records Reveal Changes in Avian Spring and Autumn Migration Timing in a Coastal Forest Near Niigata

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Efficacy and Safety of Prunus Mume and Choline in Patients with Abnormal Level of Liver Function Test

International Journal of Clinical Trials Aslam MN et al. Int J Clin Trials. 2020 Aug;7(3):170-175 http://www.ijclinicaltrials.com pISSN 2349-3240 | eISSN 2349-3259 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18203/2349-3259.ijct20203103 Original Research Article Efficacy and safety of Prunus mume and choline in patients with abnormal level of liver function test Muhammad N. Aslam1, Anwar Ali2, Suresh Kumar3* 1Department of Gastroenterology, Mayo Hospital, Lahore, Pakistan 2Department of Medicine, Saidu Group of Teaching Hospital, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan 3Department of Medicine, Rafa-e-Aam Hospital, Sindh, Pakistan Received: 18 March 2020 Revised: 27 April 2020 Accepted: 30 April 2020 *Correspondence: Dr. Suresh Kumar, E-mail: [email protected] Copyright: © the author(s), publisher and licensee Medip Academy. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. ABSTRACT Background: The objectives of the study were to determine the efficacy and safety of Prunus mume and choline in patients with abnormal liver function test. Methods: This open labelled, multi-centered observational study was done for a from May 2019 to December 2019. Patients of either gender, above 18 years of age having elevated levels of aspartate aminotransferase, alanine transaminase or gamma-glutamyltransferase were included in the study after taking informed consent. One to two tablets of revolic per day were given preferably in the morning with breakfast or as per instructions of the physician. Patient follow-ups were done at 2nd and 4th week after treatment. -

Natural History of Japanese Birds

Natural History of Japanese Birds Hiroyoshi Higuchi English text translated by Reiko Kurosawa HEIBONSHA 1 Copyright © 2014 by Hiroyoshi Higuchi, Reiko Kurosawa Typeset and designed by: Washisu Design Office Printed in Japan Heibonsha Limited, Publishers 3-29 Kanda Jimbocho, Chiyoda-ku Tokyo 101-0051 Japan All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher. The English text can be downloaded from the following website for free. http://www.heibonsha.co.jp/ 2 CONTENTS Chapter 1 The natural environment and birds of Japan 6 Chapter 2 Representative birds of Japan 11 Chapter 3 Abundant varieties of forest birds and water birds 13 Chapter 4 Four seasons of the satoyama 17 Chapter 5 Active life of urban birds 20 Chapter 6 Interesting ecological behavior of birds 24 Chapter 7 Bird migration — from where to where 28 Chapter 8 The present state of Japanese birds and their future 34 3 Natural History of Japanese Birds Preface [BOOK p.3] Japan is a beautiful country. The hills and dales are covered “satoyama”. When horsetail shoots come out and violets and with rich forest green, the river waters run clear and the moun- cherry blossoms bloom in spring, birds begin to sing and get tain ranges in the distance look hazy purple, which perfectly ready for reproduction. Summer visitors also start arriving in fits a Japanese expression of “Sanshi-suimei (purple mountains Japan one after another from the tropical regions to brighten and clear waters)”, describing great natural beauty. -

Pale-Legged Leaf Warbler: New to Britain

Pale-legged Leaf Warbler: new to Britain John Headon, J. Martin Collinson and Martin Cade Abstract A Pale-legged Leaf Warbler Phylloscopus tenellipes was discovered dead after hitting a window at the lighthouse on St Agnes, Isles of Scilly, on 21st October 2016. Feathers taken from the bird were sent for DNA analysis, which confirmed the bird to be a Pale-legged Leaf Warbler and eliminated the morphologically similar Sakhalin Leaf Warbler P. borealoides. An earlier record of one of this species pair from Portland, Dorset, on 22nd October 2012 concerned a bird photographed and seen well by several observers, but it was not possible to establish which species was involved. Full details of both sightings are described here. This is the first record of Pale-legged Leaf Warbler for Britain and the Western Palearctic, and the species has been added to Category A of the British List. Pale-legged Leaf Warbler on Scilly t around midday on 21st October point Pale-legged Leaf P. tenellipes and 2016, Laurence Pitcher (LP) was Sakhalin Leaf Warbler P. borealoides were not A eating a pasty outside the lighthouse species that crossed my mind, but several on St Agnes in the Isles of Scilly when the people responded immediately – notably owner, Fran Hicks (FH), came over for a James Gilroy, Chris Batty and Andrew Holden chat. They bemoaned the lack of migrants on (AH) – with these very suggestions. AH hap- the island, but in parting FH casually men- pened to be on the island and soon arrived at tioned that a Phylloscopus warbler had struck the lighthouse. -

Nov. 24Th – 7:00 Pm by Zoom Doors Will Open at 6:30

Wandering November 2020 Volume 70, Number 3 Tattler The Voice of SEA AND SAGE AUDUBON, an Orange County Chapter of the National Audubon Society Why Do Birders Count Birds? General Meeting - Online Presentation th Gail Richards, President Friday, November 20 – 7:00 PM Via Zoom Populations of birds are changing, both in the survival of each species and the numbers of birds within each “Motus – an exciting new method to track species. In California, there are 146 bird species that are vulnerable to extinction from climate change. These the movements of birds, bats, & insects” fluctuations may indicate shifts in climate, pollution levels, presented by Kristie Stein, MS habitat loss, scarcity of food, timing of migration or survival of offspring. Monitoring birds is an essential part of protecting them. But tracking the health of the world’s 10,000 bird species is an immense challenge. Scientists need thousands of people reporting what they are seeing in their back yards, neighborhoods, parks, nature preserves and in all accessible wild areas. Even though there are a number of things we are unable to do during this pandemic, Sea and Sage volunteers are committed to continuing bird surveys (when permitted, observing Covid-19 protocols). MONTHLY SURVEYS: Volunteers survey what is out there, tracking the number of species and their abundance. San Joaquin Wildlife Sanctuary UCI Marsh Kristie Stein is a Wildlife Biologist with the Southern University Hills Eco Reserve Sierra Research Station (SSRS) in Weldon, California. Upper Newport Bay by pontoon boat Her research interests include post-fledging ecology, seasonal interactions and carry-over effects, and SEASONAL SURVEYS AND/OR MONITORING: movement ecology. -

米埔的鳥類mai Po Birds

米埔的鳥類 Mai Po Birds 前言 Foreword 本「米埔鳥類名錄」(包括米埔及內后海灣拉姆薩爾濕地及鄰近濕地地區範圍)共記錄 426 個野生鳥類物種(即香港鳥類名錄中類別 I 及 II 之鳥類),記錄於本名錄 A 部份。當中 400 個物種曾在「米埔自然保護區及中心」範圍(圖 1)內錄得,在本名錄以「*」號表示。 其他與逃逸或放生的籠鳥相關的米埔鳥類物種,記錄於本名錄 B 部份(即香港鳥類名錄中類別 III 之鳥類)。 This “Mai Po bird species list” hold over 400 wild bird species (i.e. Category I of the Hong Kong Bird Species List), recorded from the Mai Po and Inner Deep Bay Ramsar Site and its vicinity wetland area. They are shown in Section A of this list. Over 370 of these species have been recorded inside the “Mai Po Nature Reserve and Centers” boundary (Fig 1). They are marked with an asterisk (*) in this list. Other Mai Po species for which records are considered likely to relate to birds that have escaped or have been released from captivity are shown in Section B of this list (i.e. Category II and III of the Hong Kong Bird Species List). 圖 1. 米埔自然保護區及中心 Fig. 1 Mai Po Nature Reserve and Centers Credit: Google Earth 2010 1 Last update: May 2019 最後更新日期:2019 年 5 月 A 部份 Section A: 中文名稱 英文名稱 學名 全球保育狀況 1 * Chinese Name English Name Scientific Name Global Conservation Status1 雁鴨科 DUCKS, GEESE AND SWANS Anatidae * 栗樹鴨 Lesser Whistling Duck Dendrocygna javanica * 灰雁 Greylag Goose Anser anser * 寒林豆雁 Taiga Bean Goose Anser fabalis * 凍原豆雁 Tundra Bean Goose Anser serrirostris * 白額雁 Greater White-fronted Goose Anser albifrons * 小白額雁 Lesser White-fronted Goose Anser erythropus 易危 Vulnerable * 大天鵝 Whooper Swan Cygnus cygnus * 翹鼻麻鴨 Common Shelduck Tadorna tadorna * 赤麻鴨 Ruddy Shelduck Tadorna ferruginea * 鴛鴦 Mandarin Duck Aix galericulata * 棉鳧 -

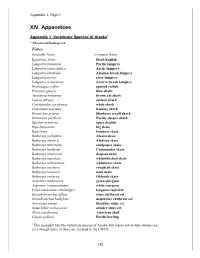

XIV. Appendices

Appendix 1, Page 1 XIV. Appendices Appendix 1. Vertebrate Species of Alaska1 * Threatened/Endangered Fishes Scientific Name Common Name Eptatretus deani black hagfish Lampetra tridentata Pacific lamprey Lampetra camtschatica Arctic lamprey Lampetra alaskense Alaskan brook lamprey Lampetra ayresii river lamprey Lampetra richardsoni western brook lamprey Hydrolagus colliei spotted ratfish Prionace glauca blue shark Apristurus brunneus brown cat shark Lamna ditropis salmon shark Carcharodon carcharias white shark Cetorhinus maximus basking shark Hexanchus griseus bluntnose sixgill shark Somniosus pacificus Pacific sleeper shark Squalus acanthias spiny dogfish Raja binoculata big skate Raja rhina longnose skate Bathyraja parmifera Alaska skate Bathyraja aleutica Aleutian skate Bathyraja interrupta sandpaper skate Bathyraja lindbergi Commander skate Bathyraja abyssicola deepsea skate Bathyraja maculata whiteblotched skate Bathyraja minispinosa whitebrow skate Bathyraja trachura roughtail skate Bathyraja taranetzi mud skate Bathyraja violacea Okhotsk skate Acipenser medirostris green sturgeon Acipenser transmontanus white sturgeon Polyacanthonotus challengeri longnose tapirfish Synaphobranchus affinis slope cutthroat eel Histiobranchus bathybius deepwater cutthroat eel Avocettina infans blackline snipe eel Nemichthys scolopaceus slender snipe eel Alosa sapidissima American shad Clupea pallasii Pacific herring 1 This appendix lists the vertebrate species of Alaska, but it does not include subspecies, even though some of those are featured in the CWCS. -

Vol.25 No.2 Summer 2014

Bermuda Audubon Society NEWSLETTER Summer 2014 P.O. Box HM 1328, Hamilton HM FX Vol.25 No.2 www.audubon.bm Email: [email protected] In this issue: Audubon at 60 Andrew Dobson The Bermuda Audubon Society 1954-2014 Karen Border Arctic Warbler – new to Bermuda and the east coast of North America Andrew Dobson Confirmation of the Common Raven as a new record for Bermuda David B. Wingate Bird Report January to May 2014 Andrew Dobson Society News Audubon at 60 I was lucky enough to be present at the Society’s 40th anniversary in 1994 when American ornithologist Kenn Kaufman addressed a large gathering at the Hamilton Princess Hotel. Ten years later we celebrated once again in style at Horizons with a fascinating talk presented by Australian ornithologist Nick Carlile who worked closely with Jeremy Madeiros in the Cahow translocation project. For the 50th anniversary we also produced a special magazine which includes a detailed history of the Society (and available on the BAS website under ‘Newsletters). In the introduction to his article, David Wingate wrote, “In 1954, a small group of local naturalists got together to address growing environmental concerns in Bermuda. The tragic loss of the once dominant Bermuda cedar due to the scale epidemic of the late 1940s, and the establishment of the starling as another nest site competitor along with the sparrow, was threatening the imminent demise of the native bluebird. There was also a government policy of filling in the marshes by using them as garbage dumps. But it was a time of hope too, because the Cahow had just been rediscovered in 1951.” How quickly another 10 years have passed. -

Prunus Mume Japanese Apricot1 Edward F

Fact Sheet ST-512 October 1994 Prunus mume Japanese Apricot1 Edward F. Gilman and Dennis G. Watson2 INTRODUCTION Japanese Flowering Apricot may be the longest- lived of the flowering fruit trees eventually forming a gnarled, picturesque, 20-foot-tall tree (Fig. 1). Appearing during the winter on bare branches are the multitude of small, fragrant, pink flowers which add to the uniqueness of the tree’s character. The small yellow fruits which follow the blooms are inedible but attractive. GENERAL INFORMATION Scientific name: Prunus mume Pronunciation: PROO-nus MEW-may Common name(s): Japanese Apricot Family: Rosaceae USDA hardiness zones: 6 through 8 (Fig. 2) Origin: not native to North America Uses: recommended for buffer strips around parking lots or for median strip plantings in the highway; near a deck or patio; specimen; no proven urban tolerance Availability: somewhat available, may have to go out of the region to find the tree DESCRIPTION Figure 1. Young Japanese Apricot. Height: 12 to 20 feet Spread: 15 to 20 feet Foliage Crown uniformity: irregular outline or silhouette Crown shape: round; vase shape Leaf arrangement: alternate (Fig. 3) Crown density: moderate Leaf type: simple Growth rate: medium Leaf margin: serrate Texture: fine Leaf shape: ovate 1. This document is adapted from Fact Sheet ST-512, a series of the Environmental Horticulture Department, Florida Cooperative Extension Service, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, University of Florida. Publication date: October 1994. 2. Edward F. Gilman, associate professor, Environmental Horticulture Department; Dennis G. Watson, associate professor, Agricultural Engineering Department, Cooperative Extension Service, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, University of Florida, Gainesville FL 32611. -

Plant Gems from China©

1 Plant Gems from China© Donghui Peng1, Longqing Chen2 and Mengmeng Gu3 1College of Landscape Architecture and Horticulture, Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University, Fuzhou, Fujian Province 350002, PRC 2College of Forestry and Horticulture, Huazhong Agriculture University, Wuhan, Hubei Province 430070, PRC 3Department of Horticultural Sciences, Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service, College Station, TX 77843, USA Email: [email protected] INTRODUCTION A lot of plants native in China thrive in landscapes across the U.S. Chinese plant germplasm has been continuously introduced to the U.S., and used in breeding and selection. So many new cultivars with Chinese genetics have been introduced in the landscape plant market. The Chinese love plants and particularly enjoy ten “traditionally famous flowers”: lotus (Nelumbo nucifera), sweet olive (Osmanthus frangrans), peony (Paeonia suffruticosa), azalea (Azalea spp.), chrysanthemum (Chrysanthemum spp.), Mei flower (Prunus mume), daffodil (Narcissus spp.), rose (Rosa spp.), camellia (Camellia spp.) and cymbidium (Cymbidium spp.). Public and university breeders have focused on these taxa. In addition, many species and cultivars commonly grown in China may be of interest to growers and landscape professionals in the U.S, which this manuscript will be focused on. PLANT SPECIES AND CULTIVARS Sweet olive (Osmanthus fragrans). There are mainly four types of sweet olives, Auranticus Group, Luteus Group, Albus Group, orange and Semperflorens Group. Ever-blooming sweet 1 2 olives have peak blooming in the fall like the others, and continue for about six months although not as profusely. Recently there are three variegated cultivars: ‘Yinbian Caiye’ with white leaf margins mature leaves and red/white/green on new growth, ‘Yintian Cai’ with red-margined maroon leaves maturing to white-margined green leaves, and ‘Pearl Color’ with pink new growth. -

Print 02/03 February 2003

Song of the Dark-throated Thrush Vladimir Yu.Arkhipov, Michael G.Wilson and Lars Svensson 49. Male Dark-throated Thrush Turdus ruficollis atrogularis, Lake Ysyk-Köl, Kyrgyzstan, February 2002. Jürgen Steudtner ABSTRACT The song of the Dark-throated Thrush Turdus ruficollis of the race atrogularis (‘Black-throated Thrush’) is described from one of the first fully authenticated tape-recordings of this vocalisation, and is shown to be distinctly different from that of the race ruficollis (‘Red-throated Thrush’). Further studies of voice, mate selection, and breeding biology in general are needed for a full clarification of Dark-throated Thrush taxonomy. he Dark-throated Thrush Turdus rufi- ruficollis and atrogularis were found to be sepa- collis is considered by most recent rated by habitat, and no mixed pairs or hybrids Tauthors (e.g. Portenko 1981; Cramp were recorded (Stakheev 1979; Ernst 1992); in 1988; Glutz & Bauer 1988; Clement & Hathway Mongolia, hybridisation was reported to occur 2000) to be polytypic, comprising the red- in the northwest (Mongolian Altai and Great throated nominate race ruficollis and the black- Lakes Depression) by Fomin & Bold (1991), but throated atrogularis. The two races interbreed observations of passage ruficollis farther east in where they overlap in the east and southeast of the country showed very little evidence of the range (Clement & Hathway 2000), with hybridisation (Mauersberger 1980). Indeed, intermediates reported from the Altai, western nominate ruficollis and atrogularis were Sayan, and upper Lena and upper Nizhnyaya regarded by Stepanyan (1983, 1990) as separate Tunguska rivers (Dement’ev & Gladkov 1954). species, and this view was shared by others, The situation is by no means clear-cut, including Evans (1996) ‘based primarily on however: in, for example, the Altai (Russia), plumage and ecological differences’, but also © British Birds 96 • February 2003 • 79-83 79 Song of the Dark-throated Thrush Stephan Ernst 50. -

Downloading Or Purchasing Online At

Commercialisation of Mume in Australia April 2015 RIRDC Publication No. 15/044 Commercialisation of mume in Australia by Bruce Topp, Dougal Russell, Grant Bignell, Janelle Dahler, Janet Giles and Judy Noller March 2015 RIRDC Publication No 15/044 RIRDC Project No PRJ-000857 © 2015 Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation. All rights reserved. ISBN 978-1-74254-788-6 ISSN 1440-6845 Commercialisation of Mume in Australia Publication No. 15/044 Project No. PRJ-000857 The information contained in this publication is intended for general use to assist public knowledge and discussion and to help improve the development of sustainable regions. You must not rely on any information contained in this publication without taking specialist advice relevant to your particular circumstances. While reasonable care has been taken in preparing this publication to ensure that information is true and correct, the Commonwealth of Australia gives no assurance as to the accuracy of any information in this publication. The Commonwealth of Australia, the Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation (RIRDC), the authors or contributors expressly disclaim, to the maximum extent permitted by law, all responsibility and liability to any person, arising directly or indirectly from any act or omission, or for any consequences of any such act or omission, made in reliance on the contents of this publication, whether or not caused by any negligence on the part of the Commonwealth of Australia, RIRDC, the authors or contributors. The Commonwealth of Australia does not necessarily endorse the views in this publication. This publication is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, all other rights are reserved. -

A Systematic Review of Ume Health Benefits

St. Catherine University SOPHIA Master of Arts in Holistic Health Studies Research Papers Holistic Health Studies 5-2016 A Systematic Review of Ume Health Benefits Mina Christensen St. Catherine University Follow this and additional works at: https://sophia.stkate.edu/ma_hhs Part of the Alternative and Complementary Medicine Commons Recommended Citation Christensen, Mina. (2016). A Systematic Review of Ume Health Benefits. Retrieved from Sophia, the St. Catherine University repository website: https://sophia.stkate.edu/ma_hhs/4 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Holistic Health Studies at SOPHIA. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Arts in Holistic Health Studies Research Papers by an authorized administrator of SOPHIA. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Running head: A SYTEMATIC REVIEW OF UME HEALTH BENEFITS 1 A Systematic Review of Ume Health Benefits Mina Christensen St. Catherine University May 18, 2016 A SYTEMATIC REVIEW OF UME HEALTH BENEFITS ii Abstract Ume is a Japanese apricot, and Bainiku Ekisu (BE) is concentrated ume juice. Ume has been used as a food and folk remedy for thousands of years in East Asian countries, and BE was created in Japan centuries ago and has been used as a remedy since. In the Western world, the nutritional and medicinal benefits of ume and BE are not popularly known, despite many experimental studies showing their numerous health benefits. There are no known systematic reviews of the health benefits of ume and BE. Therefore, this systematic review describes the last 20 years of quality empirical studies that investigate ume and BE health benefits.