Pale-Legged Leaf Warbler: New to Britain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Natural History of Japanese Birds

Natural History of Japanese Birds Hiroyoshi Higuchi English text translated by Reiko Kurosawa HEIBONSHA 1 Copyright © 2014 by Hiroyoshi Higuchi, Reiko Kurosawa Typeset and designed by: Washisu Design Office Printed in Japan Heibonsha Limited, Publishers 3-29 Kanda Jimbocho, Chiyoda-ku Tokyo 101-0051 Japan All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher. The English text can be downloaded from the following website for free. http://www.heibonsha.co.jp/ 2 CONTENTS Chapter 1 The natural environment and birds of Japan 6 Chapter 2 Representative birds of Japan 11 Chapter 3 Abundant varieties of forest birds and water birds 13 Chapter 4 Four seasons of the satoyama 17 Chapter 5 Active life of urban birds 20 Chapter 6 Interesting ecological behavior of birds 24 Chapter 7 Bird migration — from where to where 28 Chapter 8 The present state of Japanese birds and their future 34 3 Natural History of Japanese Birds Preface [BOOK p.3] Japan is a beautiful country. The hills and dales are covered “satoyama”. When horsetail shoots come out and violets and with rich forest green, the river waters run clear and the moun- cherry blossoms bloom in spring, birds begin to sing and get tain ranges in the distance look hazy purple, which perfectly ready for reproduction. Summer visitors also start arriving in fits a Japanese expression of “Sanshi-suimei (purple mountains Japan one after another from the tropical regions to brighten and clear waters)”, describing great natural beauty. -

Nov. 24Th – 7:00 Pm by Zoom Doors Will Open at 6:30

Wandering November 2020 Volume 70, Number 3 Tattler The Voice of SEA AND SAGE AUDUBON, an Orange County Chapter of the National Audubon Society Why Do Birders Count Birds? General Meeting - Online Presentation th Gail Richards, President Friday, November 20 – 7:00 PM Via Zoom Populations of birds are changing, both in the survival of each species and the numbers of birds within each “Motus – an exciting new method to track species. In California, there are 146 bird species that are vulnerable to extinction from climate change. These the movements of birds, bats, & insects” fluctuations may indicate shifts in climate, pollution levels, presented by Kristie Stein, MS habitat loss, scarcity of food, timing of migration or survival of offspring. Monitoring birds is an essential part of protecting them. But tracking the health of the world’s 10,000 bird species is an immense challenge. Scientists need thousands of people reporting what they are seeing in their back yards, neighborhoods, parks, nature preserves and in all accessible wild areas. Even though there are a number of things we are unable to do during this pandemic, Sea and Sage volunteers are committed to continuing bird surveys (when permitted, observing Covid-19 protocols). MONTHLY SURVEYS: Volunteers survey what is out there, tracking the number of species and their abundance. San Joaquin Wildlife Sanctuary UCI Marsh Kristie Stein is a Wildlife Biologist with the Southern University Hills Eco Reserve Sierra Research Station (SSRS) in Weldon, California. Upper Newport Bay by pontoon boat Her research interests include post-fledging ecology, seasonal interactions and carry-over effects, and SEASONAL SURVEYS AND/OR MONITORING: movement ecology. -

米埔的鳥類mai Po Birds

米埔的鳥類 Mai Po Birds 前言 Foreword 本「米埔鳥類名錄」(包括米埔及內后海灣拉姆薩爾濕地及鄰近濕地地區範圍)共記錄 426 個野生鳥類物種(即香港鳥類名錄中類別 I 及 II 之鳥類),記錄於本名錄 A 部份。當中 400 個物種曾在「米埔自然保護區及中心」範圍(圖 1)內錄得,在本名錄以「*」號表示。 其他與逃逸或放生的籠鳥相關的米埔鳥類物種,記錄於本名錄 B 部份(即香港鳥類名錄中類別 III 之鳥類)。 This “Mai Po bird species list” hold over 400 wild bird species (i.e. Category I of the Hong Kong Bird Species List), recorded from the Mai Po and Inner Deep Bay Ramsar Site and its vicinity wetland area. They are shown in Section A of this list. Over 370 of these species have been recorded inside the “Mai Po Nature Reserve and Centers” boundary (Fig 1). They are marked with an asterisk (*) in this list. Other Mai Po species for which records are considered likely to relate to birds that have escaped or have been released from captivity are shown in Section B of this list (i.e. Category II and III of the Hong Kong Bird Species List). 圖 1. 米埔自然保護區及中心 Fig. 1 Mai Po Nature Reserve and Centers Credit: Google Earth 2010 1 Last update: May 2019 最後更新日期:2019 年 5 月 A 部份 Section A: 中文名稱 英文名稱 學名 全球保育狀況 1 * Chinese Name English Name Scientific Name Global Conservation Status1 雁鴨科 DUCKS, GEESE AND SWANS Anatidae * 栗樹鴨 Lesser Whistling Duck Dendrocygna javanica * 灰雁 Greylag Goose Anser anser * 寒林豆雁 Taiga Bean Goose Anser fabalis * 凍原豆雁 Tundra Bean Goose Anser serrirostris * 白額雁 Greater White-fronted Goose Anser albifrons * 小白額雁 Lesser White-fronted Goose Anser erythropus 易危 Vulnerable * 大天鵝 Whooper Swan Cygnus cygnus * 翹鼻麻鴨 Common Shelduck Tadorna tadorna * 赤麻鴨 Ruddy Shelduck Tadorna ferruginea * 鴛鴦 Mandarin Duck Aix galericulata * 棉鳧 -

Eastern Crowned Warbler in Co. Durham: New to Britain Dougie Holden and Mark Newsome Ren Hathway

Eastern Crowned Warbler in Co. Durham: new to Britain Dougie Holden and Mark Newsome Ren Hathway Abstract Britain’s first Eastern Crowned Warbler Phylloscopus coronatus was discovered at Trow Quarry, South Shields, Co. Durham, on 22nd October 2009, where it remained until 24th October. The South Shields bird followed others in Norway, Finland and the Netherlands between 2002 and 2007, plus one on Helgoland, Germany, in 1843. This paper describes its discovery, and discusses the species’ distribution and previous European records. hursday 22nd October 2009 was my Warbler Phylloscopus inornatus was top of my 26th wedding anniversary, and not one list, as I knew that one or two had been seen Tthat I’m likely to forget in a hurry. along the Durham coastline in previous days. Unbeknown to my wife, Lynne, I’d arranged The morning was good, headlined by time off work so that we could spend the day seeing not one but two Short-eared Owls together, but I was unaware of an earlier Asio flammeus coming in off the sea at The commitment of hers that couldn’t be broken. Leas, plus a range of commoner migrants Consequently, I settled for birding my local there and at Trow Quarry: Robins Erithacus patch on the Durham coast; the wind was rubecula and Blackbirds Turdus merula were easterly and I was optimistic. Yellow-browed present in good numbers, Redwings T. iliacus © British Birds 104 • June 2011 • 303–311 303 Holden & Newsome and Fieldfares T. pilaris were flying overhead, this in the only book I had readily to hand, but there was nothing out of the ordinary. -

Vol.25 No.2 Summer 2014

Bermuda Audubon Society NEWSLETTER Summer 2014 P.O. Box HM 1328, Hamilton HM FX Vol.25 No.2 www.audubon.bm Email: [email protected] In this issue: Audubon at 60 Andrew Dobson The Bermuda Audubon Society 1954-2014 Karen Border Arctic Warbler – new to Bermuda and the east coast of North America Andrew Dobson Confirmation of the Common Raven as a new record for Bermuda David B. Wingate Bird Report January to May 2014 Andrew Dobson Society News Audubon at 60 I was lucky enough to be present at the Society’s 40th anniversary in 1994 when American ornithologist Kenn Kaufman addressed a large gathering at the Hamilton Princess Hotel. Ten years later we celebrated once again in style at Horizons with a fascinating talk presented by Australian ornithologist Nick Carlile who worked closely with Jeremy Madeiros in the Cahow translocation project. For the 50th anniversary we also produced a special magazine which includes a detailed history of the Society (and available on the BAS website under ‘Newsletters). In the introduction to his article, David Wingate wrote, “In 1954, a small group of local naturalists got together to address growing environmental concerns in Bermuda. The tragic loss of the once dominant Bermuda cedar due to the scale epidemic of the late 1940s, and the establishment of the starling as another nest site competitor along with the sparrow, was threatening the imminent demise of the native bluebird. There was also a government policy of filling in the marshes by using them as garbage dumps. But it was a time of hope too, because the Cahow had just been rediscovered in 1951.” How quickly another 10 years have passed. -

Biodiversity Assessment of the REDD Community Forest Project in Oddar Meanchey Cambodia

Biodiversity Assessment of the REDD Community Forest Project in Oddar Meanchey Cambodia January 2011 BirdLife International has its origins in the Founded in 1971, Pact is an international International Council for Bird Preservation (ICBP), development organization headquartered in the which was founded in 1922. In 1994, the ICBP was United States with twenty-four offices around the restructured to create a global Partnership of world. Pact’s work centers on building empowered national conservation organisations and was communities, effective governments and renamed BirdLife International. Today, the BirdLife responsible private institutions that give people an International Partnership is a global network of opportunity for a better life. Pact has maintained national, membership-based NGO Partners, who an office in Cambodia since 1991 and is registered are working in over 100 countries for the with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. One of Pact’s sustainable use and management of the world's main program areas is community based natural natural resources. BirdLife has been active in resource management, geared for identifying and Cambodia since 1996 and is registered with the engaging the range of stakeholders that depend on Ministry of ForeignAffairs. BirdLife has operational or affect the management of natural resources. Our memoranda of understanding with the Ministry approach engages women and other marginalized of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, and the groups in the process of decision making for Ministry of Environment. BirdLife works on natural resource management. shared projects and programmes with these two ministries to strengthen the protected areas, promoting sustainability in the use of natural resources and the equitable sharing of benefits arising to reduce poverty. -

The Birds of the Wenyu

The Birds of the Wenyu Beijing’s Mother River Steve Bale 史進 1 Contents Introduction Page 3 The Status, The Seasons, The Months Page 9 The Birds Page 10 Finding Birds on the Wenyu Page 172 The List of the ‘New’ Birds for the Wenyu Page 178 Special Thanks Page 186 Free to Share… Page 187 References Page 188 2 Introduction In the meeting of the Zoological Society of London on the 22nd November 1842, John Gould (1804-81) presented what was described in the Society’s proceedings as a “new species of Parrot” 1. The impressively marked bird had been collected on the Marquesas Islands – a remote spot of the Pacific Ocean that would become part of French Polynesia. The members of the Society present at that meeting would have undoubtedly been impressed by yet another of the rare, exotic gems that Gould had a habit of pulling out of his seemingly bottomless hat. Next up in this Victorian frontiers-of-ornithology ‘show and tell’ was Hugh Edwin Strickland (1811-53). The birds he spoke about2 were quite a bit closer to home, although many were every bit as exotic as Gould’s Polynesian parrot. Strickland, instead of sourcing his specimens from the far corners of the Earth, had simply popped across London to Hyde Park Corner with his note book. There, causing quite a stir, was an exhibition of "Ten Thousand Chinese Things", displayed in a purpose-built “summer house” whose design was, according to The Illustrated London News3, “usual in the gardens of the wealthy, in the southern provinces of China”. -

Tue Orientation of Pallas's Leaf Warbler Phylloscopus Proregulus in Europe

Tue orientation of Pallas's Leaf Warbler Phylloscopus proregulus in Europe JØRGEN RABØL (Med et dansk resume: Fuglekongesangerens Phylloscopus proregulus orientering i Europa) THE MIGRATORY PROGRAMME periments carried out especially by Perdeck (1958). One of the most puzzling problems in present orientational research is whether the routes of Compensation for displacement migratory hirds are hereditarily programmed Until recently it was thought possible to on the basis,of one-direction orientation only, distinguish and demonstrate one-direction, or whether bi(multi)coordinate navigation is orientation and bicoordinate navigation by also involved ( e.g. Wallraff 1972). the reactions following displacement of migrating birds (e.g. Perdeck 1958, and Definitions Rabøl 1969a). If the displacement was One-direction (or compass) orientation followed by a directional shift towards the denotes orientation at a fixed angle deter original migratory route or the wintering mined by an extrinsic stimulus. This stimulus ground, the presence of bicoordinate could be the azimuth of the sun (Matthews navigation was demonstrated. 1968) or the polar star (the axis of rotation, It was thus in contradiction to the common Emlen 1970), or the inclination of the earth's view that Evans ( 1968) and Rabøl ( 1969a, magnetic field (Wiltschko et. al. 1971), for 1970, 1972) found that juvenile chats and example. warblers on their first autumn migration also Bicoordinate navigation involves the compensated for displacement and oriented measurement of the values of two parameters. towards their migratory route. Furthermore, Nothing is known about the nature of these Rabøl ( 1969a, 1970, 1972) concluded that parameters, but time and polar star altitude the juvenile birds navigated towards goal could be imagined, for example (Rabøl areas on the migratory route. -

Bhutan March 26–April 14, 2019

BHUTAN MARCH 26–APRIL 14, 2019 The Satyr Tragopan is one of the best pheasants on our planet! Photo by M. Valkenburg LEADER: MACHIEL VALKENBURG LIST COMPILED BY: MACHIEL VALKENBURG VICTOR EMANUEL NATURE TOURS, INC. 2525 WALLINGWOOD DRIVE, SUITE 1003 AUSTIN, TEXAS 78746 WWW.VENTBIRD.COM BHUTAN March 26–April 14, 2019 By Machiel Valkenburg Our annual adventure to Bhutan started in Delhi, where we all came together for the flight to Paro in Bhutan. The birding here started immediately outside of the airport parking lot, finding the wonderful Ibisbill, which we quickly located in the wide stream along the airport road. It seemed to be a cold spring, with quite an amount of snow still on the surrounding peaks. Our visit to the Cheli La (La means pass) was good for some new surprises like Snow Pigeon and Alpine Accentor. We found Himalayan White- browed Rosefinch feeding in an alpine meadow, and then suddenly two Himalayan Monals appeared and showed very well. Here we were happy with extra sightings of Blood Pheasant, Black Eagle, Blue-fronted Redstart, and Yellow-billed Blue-Magpie. After Paro, we started our journey east with a drive to Thimphu and Punakha, visiting Dochu La and Tashitang along the way. The birding in these places is nothing but spectacular with great sightings constantly. These lush green valleys are very photogenic, and many stops were made to take in all the landscapes. The birding was good here with excellent sightings of a crossing Hill Partridge, some exquisite Ultramarine Flycatchers, a close overhead Rufous-bellied Eagle, a surprise sighting of a day- roosting Tawny Fish-Owl, and some wonderful scope views of a party of Gray Treepies. -

Herefore Takes Precedence

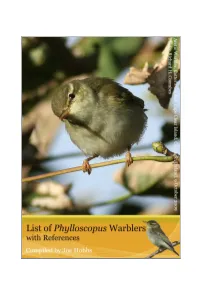

Introduction I have endeavored to keep typos, errors etc in this list to a minimum, however when you find more I would be grateful if you could mail the details during 2011 to: [email protected]. Grateful thanks to Dick Coombes for the cover images. Joe Hobbs Index The general order of species follows the International Ornithological Congress’ World Bird List. Version Version 1.9 (1 August 2011). Cover Main image: Arctic Warbler. Cotter’s Garden, Cape Clear Island, Co. Cork, Ireland. 9 October 2009. Richard H. Coombes. Vignette: Arctic Warbler. The Waist, Cape Clear Island, Co. Cork, Ireland. 10 October 2009. Richard H. Coombes. Species Page No. Alpine Leaf Warbler [Phylloscopus occisinensis] 17 Arctic Warbler [Phylloscopus borealis] 24 Ashy-throated Warbler [Phylloscopus maculipennis] 20 Black-capped Woodland Warbler [Phylloscopus herberti] 5 Blyth’s Leaf Warbler [Phylloscopus reguloides] 31 Brooks’ Leaf Warbler [Phylloscopus subviridis] 22 Brown Woodland Warbler [Phylloscopus umbrovirens] 5 Buff-barred Warbler [Phylloscopus pulcher] 19 Buff-throated Warbler [Phylloscopus subaffinis] 17 Canary Islands Chiffchaff [Phylloscopus canariensis] 12 Chiffchaff [Phylloscopus collybita] 8 Chinese Leaf Warbler [Phylloscopus yunnanensis] 20 Claudia’s Leaf Warbler [Phylloscopus claudiae] 31 Davison’s Leaf Warbler [Phylloscopus davisoni] 32 Dusky Warbler [Phylloscopus fuscatus] 15 Eastern Bonelli's Warbler [Phylloscopus orientalis] 14 Eastern Crowned Warbler [Phylloscopus coronatus] 30 Emei Leaf Warbler [Phylloscopus emeiensis] 32 Gansu Leaf Warbler -

Mt. Mitutouge, Fuji Area, Japan

BIRD TOURISM REPORTS 6/2016 Petri Hottola MT. MITUTOUGE, FUJI AREA, JAPAN Fig. 1. N’EX route from Narita Airport to Kawaguchiko, in the Mt. Fuji area. In 2016, July 1st to 4th, I had a stop-over in Tokyo, between two other birding destinations, Peru and Indonesia. The time in Japan was spent, in addition to enjoying Japan in general, in an attempt to try to find a Japanese Leaf Warbler (meboso-mushikui), one of the two breeding species I still missed on the main islands of Japan (excluding Ryukyu and Bonin islands). As it turned out to be, I did not only find three Japanese Leaf Warblers but also stumbled on a Japanese Night Heron, the other missing bird species! The Japanese Leaf Warbler (Phylloscopus xanthodryas) is an interesting taxonomical discovery. Originally, it was thought be a subspecies of Arctic Warbler (P.borealis), but was split as a southern subspecies of Kamchatka Leaf Warbler (P.examinandus). At some point, somebody noted that it had a very different song and a closer look was taken. There are morphological (larger than the other two) and plumage differences (in general, more olive/yellow), too. Locating a Japanese Leaf Warbler by its song is exceptionally easy, because of their strange territorial behavior. Unlike most other passerines, they keep on singing from late May to early October, the whole length of their breeding season stay in Japan! The following text has been provided for other birders visiting Japan, not only for those two species, but for Mt. Mitutouge (also known as Mt. Mitsutoge, or Mitsu-toge). -

Forest Bird Fauna of South China: Notes on Current Distribution and Status

FORKTAIL 22 (2006): 23–38 Forest bird fauna of South China: notes on current distribution and status LEE KWOK SHING, MICHAEL WAI-NENG LAU, JOHN R. FELLOWES and CHAN BOSCO PUI LOK From 1997 to 2004, a team from Hong Kong and southern China conducted rapid biodiversity surveys in 54 forest areas in the provinces of Guangdong, Guangxi and Hainan. A total of 372 bird species were recorded (201 in Guangdong, 299 in Guangxi and 164 in Hainan), including 12 globally threatened species, 50 China Key Protected Species and 44 species outside their previously recorded ranges. Breeding was confirmed for 94 species. In total, 232 species (62%) were recorded at five sites or fewer (2–10%). These include species at the edge of their range, migratory and wintering species inadequately sampled by these surveys, species more characteristic of non- forest habitats, and less conspicuous species that were under-recorded, but also rare and localised species. Of particular conservation concern are the globally threatened White-eared Night Heron Gorsachius magnificus, Cabot’s Tragopan Tragopan caboti, Hainan Partridge Arborophila ardens, White-necklaced Partridge Arborophila gingica, Fairy Pitta Pitta nympha, Pale-capped Pigeon Columba punicea, Brown-chested Jungle Flycatcher Rhinomyias brunneata and Gold-fronted Fulvetta Alcippe variegaticeps, and other species highly dependent on the region’s forests, such as Hainan Peacock Pheasant Polyplectron katsumatae, Pale-headed Woodpecker Gecinulus grantia, Blue-rumped Pitta Pitta soror, Swinhoe’s Minivet Pericrocotus cantonensis and Fujian Niltava Niltava davidi. At most of the sites visited, the main threat is habitat loss and degradation, especially clearance of natural forest for timber and agriculture; most remaining natural forests are fragmented and small in size.