The Historical Review/La Revue Historique

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

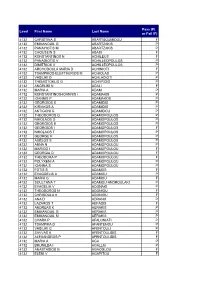

Results Level 3

Pass (P) Level First Name Last Name or Fail (F) 4132 CHRISTINA S ABARTSOUMIDOU F 4132 EMMANOUIL G ABARTZAKIS P 4132 PANAYIOTIS M ABARTZAKIS P 4132 CHOUSEIN S ABASI F 4132 KONSTANTINOS N ACHILEUS F 4132 PANAGIOTIS V ACHILLEOPOULOS P 4132 DIMITRIOS V ACHILLEOPOULOS P 4132 ARCHODOULA MARIA D ACHINIOTI F 4132 TSAMPIKOS-ELEFTHERIOS M ACHIOLAS P 4132 VASILIKI D ACHLADIOTI P 4132 THEMISTOKLIS G ACHYRIDIS P 4132 ANGELIKI N ADALI F 4132 MARIA A ADAM P 4132 KONSTANTINOS-IOANNIS I ADAMAKIS P 4132 IOANNIS P ADAMAKOS P 4132 GEORGIOS S ADAMIDIS P 4132 KIRIAKOS A ADAMIDIS P 4132 ANTIGONI G ADAMIDOU P 4132 THEODOROS G ADAMOPOULOS P 4132 NIKOLAOS G ADAMOPOULOS P 4132 GEORGIOS E ADAMOPOULOS P 4132 GEORGIOS I ADAMOPOULOS F 4132 NIKOLAOS T ADAMOPOULOS P 4132 GEORGE K ADAMOPOULOS P 4132 AGELOS S ADAMOPOULOS P 4132 ANNA N ADAMOPOULOU P 4132 MARIGO I ADAMOPOULOU F 4132 GEORGIA D ADAMOPOULOU F 4132 THEODORA P ADAMOPOULOU F 4132 POLYXENI A ADAMOPOULOU P 4132 IOANNA S ADAMOPOULOU P 4132 FOTIS S ADAMOS F 4132 EVAGGELIA A ADAMOU P 4132 MARIA G ADAMOU F 4132 SOULTANA T ADAMOU-ANDROULAKI P 4132 EVAGELIA V ADONAKI P 4132 THEODOROS N ADONIOU F 4132 CHRISOULA K ADONIOU F 4132 ANA D ADRANJI P 4132 LAZAROS T AEFADIS F 4132 ANDREAS K AERAKIS P 4132 EMMANOUIL G AERAKIS P 4132 EMMANOUIL M AERAKIS P 4132 CHARA P AFALONIATI P 4132 TSAMPIKA D AFANTENOU P 4132 VASILIKI G AFENTOULI P 4132 SAVVAS A AFENTOULIDIS F 4132 ALEXANDROS P AFENTOULIDIS F 4132 MARIA A AGA P 4132 BRUNILDA I AGALLIU P 4132 ANASTASIOS G AGAOGLOU F 4132 ELENI V AGAPITOU F 4132 JOHN K AGATHAGGELOS P 4132 PANAGIOTA -

CURRICULUM VITAE Dr. Ing. Prof. KIMON P. VALAVANIS Fellow, American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS)

CURRICULUM VITAE Dr. Ing. Prof. KIMON P. VALAVANIS Fellow, American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) PROFESSOR AND CHAIR Electrical & Computer Engineering Director, DU Unmanned Systems Research Institute (DU2SRI) School of Engineering & Computer Science, University of Denver (DU) Clarence M. Knudson Hall, Suite 300 Denver, CO 80208-1500 Phone/Fax: (303) 871-2586 / (303) 871-2194 [email protected], http://www.ece.du.edu/kvalavanis KS&P Technologies, LLC President and CEO [email protected], www.ksp-technologies.com International Conference on Unmanned Aircraft Systems (ICUAS) Association, Inc. President and Founder, Member of the Advisory Committee [email protected], http://www.icuas.com Personal Information: Citizenship: U.S. Citizen, and Native of Greece Home Address: The Boulevard, 150 W, 9th Avenue, Unit 3411 Denver, CO 80204 E-mail: [email protected] CAREER OBJECTIVES To seek challenging positions in the Engineering domain that require educational, research and development, leadership, entrepreneurial, organizational and managerial skills. To lead and enhance University Departments and Colleges, Research and Development Centers, and develop interdisciplinary programs emphasizing research cooperation and collaboration between academe, government and industry, facilitating technology transfer from the laboratories to the market. To lead in establishing the 21st Century University that will produce graduates with breadth and depth of knowledge, and with entrepreneurial skills. To seek challenging -

Yearbook 1998 Ημερολογιον 1998

ÅËËÇÍÉÊÇÏÑÈÏÄÏÎÏÓÁÑXÉÅpÉÓÊÏpÇÁÌÅÑÉÊÇÓ ÇÌÅÑÏËÏÃÉÏÍ 1998 St. Andrew, the First-Called St. Paul - Patron Saint Patron Saint of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America 1922 1998 76th Anniversary YEARBOOK 1998 GREEK ORTHODOX ARCHDIOCESE OF AMERICA 1 THE ARCHDIOCESE IS CLOSED ON THE FOLLOWING RELIGIOUS AND SPECIAL HOLIDAYS January 1 .................................................................... New Year’s Day January 6 ............................................................................... Epiphany January 19 ..................................................Martin Luther King Jr. Day February 16................................................................. Presidents’ Day March 25 ................................................................... The Annunciation April 17 ............................................................................... Holy Friday April 20 ...................................................................... Renewal Monday May 25 ........................................................................... Memorial Day May 28 .......................................................................... The Ascension July 4 (closed July 6).............................................. Independence Day August 15 ....................................................... Dormition of Theotokos September 7 ........................................................................ Labor Day September 14 .................................................. Exaltation of the Cross -

Curriculum Vitae

Zoi Dokou, Ph.D. Assistant Research Professor · UCONN PIRE Project Manager Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of Connecticut 261 Glenbrook Road, Storrs, CT, 06269 860- 486-5023, [email protected] U EDUCATION 2002 – 2008: Ph.D. in Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of Vermont, USA. 1997 – 2002: B.S. in Environmental Engineering, Technical University of Crete, Greece. PROFESSIONAL APPOINTMENTS 08/23/2017 – today Assistant Research Professor. Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of Connecticut, USA. Project Manager, NSF PIRE: Taming Water in Ethiopia 06/01/2016 – 08/22/2017 Postdoctoral Fellow. Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of Connecticut, USA. 01/01/2013 –31/10/2015 USenior UResearcher. Department of Natural Resources and Environment, Technological Educational Institute of Crete, Greece 01/09/2011 – 05/31/2016 USenior UResearcher and Instructor. School of Environmental Engineering, Technical University of Crete, Greece. 03/01/2008 – 08/31/2011 UPostdoctoral UResearch AssociateU. School of Environmental Engineering, Technical University of Crete, Greece. 11/12/2007 – 31/2/2008 UPostdoctoral Research AssociateU. Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of Vermont, USA. PUBLICATIONS IN PEER REVIEWED JOURNALS *denotes that lead author is a student I mentor(ed)/co-advise(d), *graduate student **undergraduate student 1. A. Pappa*, Z. Dokou and G.P. Karatzas (2017) Simulation and management of saltwater intrusion at a coastal aquifer in Crete, Greece, Desalination and Water Treatment Journal (accepted) 2. N.N. Kourgialas, G.P. Karatzas, Z. Dokou, A. Kokorogiannis (2017) Groundwater footprint methodology as policy tool for balancing water needs (agriculture & tourism) in water scarce islands - The case of Crete, Greece. -

The Protection of SGBV Victims: a Study on Women Refugees Based in Camps in Greece

MASTER’S DEGREE IN INTERNATIONAL PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION Dissertation The protection of SGBV victims: A study on women refugees based in camps in Greece Of MOYSIDOU STEFANIA Submitted as required to obtain the master's degree Specialization Diploma in International Public Administration May 2021 1 Moysidou Stefania Dissertation The protection of SGBV victims: A study on women refugees based in camps in Greece Supervisors Ms Chainoglou Kalliopi Assistant Professor Department of International and European Studies Mr Nikolos Zaikos Associate Professor Department of Balkan, Slavic and Eastern Studies 2 Abstract Greece is one of the countries affected the most from the crisis and received sharp criticism in its ability to respond to humanitarian needs of refugees, providing asylum reception facilities of minimum or inhuman standards that could not address SGBV. Aim: the focus of the present study lies mostly on the incidence of SGBV in relation to accommodation conditions, putting the emphasis on the investigation of possible violations of International Law. Methodology: a field case study based on mixed retrospective research was carried out in Northern Greece (Thessaloniki and Veroia). Structured Interview and close-ended questionnaires were used for receiving data. Sample: Respondents included 58 (31.86%) women from a total number of 182 female residents of the two camps, aged between 16 and 59 years, coming from different parts of Asia (Afghanistan, Syria, Iraq, Iran and Palestine). Results: similar data were found in the two camps regarding the incidence of SGBV (high), the place where the reported violence occurred (in the vast majority survivor’s own house), and the alleged perpetrators (principally members of the family). -

Environmental Hydraulics Final Program

International Association for Hydro-Environment Engineering and 6th International Research (IAHR) National Technical University of Athens Symposium on (NTUA) Technical Chamber Environmental of Greece (TEE) Hydraulics With the Support of 23-25 June, 2010 Athens, Greece DIVANI CARAVEL HOTEL Final Program www.iseh2010.org [email protected] International Association for National Technical Technical Chamber Hydro-Environment University of Athens of Greece (TEE) Engineering and (NTUA) Program Overview Research (IAHR) 19 6th International Symposium on Environmental Hydraulics 23-25 June, 2010, Athens, Greece TUESDAY, 22 JUNE 2010 17:00-19:00 Registration WEDNESDAY, 23 JUNE 2010 08:00-18:00 Registration Hall: Macedonia A & B 09:00-10:15 Opening Ceremony Chairpersons: N. Tamai, President of IAHR G. Christodoulou, Chairman of LOC A. Stamou, Secretary of LOC C. Theochari, Technical Chamber of Greece Opening Remarks G. Christodoulou, Chairman of LOC Welcome Addresses N. Tamai, President of IAHR C. Moutzouris, Rector of NTUA I. Alavanos, President of Technical Chamber of Greece A. Andreopoulos, Secretary General of Ministry of Environment, Energy and Cli- mate Change Official Opening General Lecture: The EU regulatory framework for water management: State of play and prospects G. Kremlis, Head of Unit “Cohesion Policy and Environmental Impact Assess- ments”, European Commission, DG Environment 10:15-10:45 Coffee Break 21 International Association for National Technical Technical Chamber 6th International Symposium on Hydro-Environment University of Athens of Greece (TEE) Engineering and (NTUA) Research (IAHR) Environmental Hydraulics 23-25 June, 2010, Athens, Greece WEDNESDAY, 23 JUNE 2010 WEDNESDAY, Hall: Macedonia A & B 10:45-11:30 Invited Lecture 1 Chairperson: J. -

TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY of CRETE School of Environmental Engineering Polytechneioupolis, 73 100 Chania, GREECE Tel: +302821037792 - Fax: +302821037846

TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY OF CRETE School of Environmental Engineering Polytechneioupolis, 73 100 Chania, GREECE Tel: +302821037792 - Fax: +302821037846 George P. Karatzas Professor and Associate Dean School of Environmental Engineering Laboratory of Geoenvironmental Engineering Technical University of Crete Polytechneioupolis, 73100 Chania, GREECE [email protected] RESEARCH/PROFESSIONAL INTERESTS Subsurface hydrology and contaminant transport, Groundwater management, subsurface remediation techniques, Global optimization techniques, Numerical simulation in porous media, surface water modeling and floods. EDUCATION Ph.D., Rutgers University Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Piscataway, New Jersey, 1992 M.S., Rutgers University Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Piscataway, New Jersey, 1987 Five year Diploma, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki School of Forestry and Natural Environment, Thessaloniki, Greece, 1982 PROFESSIONAL RECORD 2017 -: Associate Dean, Technical University of Crete, School of Environmental Engineering 2013 - 2017: Dean, Technical University of Crete, School of Environmental Engineering 2013 : Chairman, Technical University of Crete, Department of Environmental Engineering 2006 -: Professor, Technical University of Crete, Department of Environmental Engineering, Laboratory of Geoenvironmental Engineering 1 2008-2011: Chairman, Technical University of Crete, Department of Environmental Engineering 1999-2006: Associate Professor, Technical University of Crete, Department of Environmental -

ECCOMAS Congress 2016 PROGRAMME

European Community on Computational Methods in Applied Sciences ECCOMAS Congress 2016 VII European Congress on Computational Methods in Applied Sciences and Engineering June 5-10, Crete, Greece PROGRAMME Conference Secretariat: Institute of Structural Analysis and Antiseismic Research National Technical University of Athens, Greece ECCOMAS Congress 2016 7th European Congress on Computational Methods in Applied Sciences and Engineering 5-10 June 2016, Crete Island, Greece Programme Institute of Structural Analysis and Antiseismic Research School of Civil Engineering National Technical University of Athens Table of Contents Greetings ……....…………………………………………….………………………………………….…… 3 Scientific Programme Overview ………………………………………………………….………… 6 Floor Plans ……………….…………………………………………………………………………….……… 16 ECCOMAS Congress 2016 Organizing Committees ……………….…….…………….…… 19 ECCOMAS Congress 2016 Scientific Committees ………………….…….…………….…… 20 Congress Venue ……………………………………………………………………………………………. 22 Transportation ….…………..………………………………………………………………………..….... 23 Congress Information ………..……………………………………………….……….……………….. 24 Social Events …………………...……………………………………………………….……………..….. 26 Associations Meetings …….……………………………………………………..…………………….. 28 Plenary Lecturers …………..………………………..………………………………………………..….. 29 Semi-Plenary Lecturers ......………………………………………………………………………..….. 30 Keynote Lecturers ….………..…………………………………………………………………….…….. 34 Minisymposia ….…………..……………………….…………………………………..………….…….... 42 Young Investigators Minisymposium ….…………..…………………..…………………..…… 52 ECCOMAS Olympiad -

Ship-Breaking.Com Information Bulletins on Ship Demolition, # 15 - 18 from January 1St to December 31St, 2009

Ship-breaking.com Information bulletins on ship demolition, # 15 - 18 from January 1st to December 31st, 2009 Robin des Bois 2010 Ship-breaking.com Information bulletins on ship demolition Summary Global Statement 2009 : the threshold of 1,000 vessels is reached … 3 # 18, from September 25th to December 31st …..……………………........ 4 (The nuclear flea market, Europe : when there is a will there is a way, China, car ferries) # 17, from June 27th to September 24th …..………….……………………... 45 (Inconsistency in the United States, A good intention in the United Kingdom ?, the destocking continues) # 16, from April 4th to June 26th …...………………………………..………... 76 (MC Ruby, the economic crises continues, shaky policy in Bangladesh) # 15 fromJanuary 1st to April 3rd ……..……………………..………………. 101 (Goodbye Bangladesh, hello Philippines ?, car carriers, the rush continues) Press release January, 27th, 2010 Global statement 2009 of vessels sent to demolition : The threshold of 1,000 vessels is reached For four years, Robin des Bois has been studying the demolition market via the mobilisation and the analysis of over thirty different bibliographical sources. Robin des Bois counted 293 vessels sold for demolition in 2006, 288 in 2007 and 456 in 2008. In 2009, 1,006 vessels have left the waters, representing more than twice the 2008 total and three times the 2006 total. The total weight of recycled metal reached more than 8.2 million tons, five times the total amount of 2006. During this record year the pace of vessels leaving the oceans during the summer months has barely slowed down. The worldwide financial crisis weighed considerably on trade exchange; big ship owners have massively sent for demolition their oldest ships to adapt to the dropping of freight rates and to draw benefits from their recent ships. -

ASOR Annual Meeting

November 15–18 | Boston, Massachusetts Welcome to ASOR’s 2017 Annual Meeting 2–6 History of ASOR 7 Program-at-a-Glance 12–15 Members’ Meeting Agenda 15 Business Meetings and Special Events 16–17 Academic Program 20–52 Projects on Parade Poster Session 52–53 Contents Digital Archaeology Demo Showcase Posters 54–55 of 2017 Sponsors and Exhibitors 56–61 2016 Honors and Awards 65 Looking Ahead to the 2018 Annual Meeting 66 Honorific and Memorial Gifts 67 Fiscal Year 2017 Honor Roll 68–69 Table Table ASOR’s Legacy Circle 70 2017 ACOR Jordanian Travel Scholarship Recipients 70 2017 Fellowship Recipients 71 ASOR Board of Trustees 72 ASOR Committees 73–75 Institutional Members 76 Overseas Centers 77 ASOR Staff 78 BASOR Recommendation Form 79 Paper Abstracts 82–187 Projects on Parade Poster Abstracts 188–194 Digital Archaeology Demo Showcase Poster Abstracts 195–201 Index of Sessions 202–204 Index of Presenters 205–211 Wifi Information 212 Hotel Information and Floor Plans 213–215 Meeting Highlights 216 Cover photo by Selma Omerefendic ISBN 978-0-89757-107-4 ASOR PROGRAM GUIDE 2017 | 1 American Schools of Oriental Research | 2017 Annual Meeting Welcome from ASOR President, Susan Ackerman Welcome to ASOR’s 2017 Annual Meeting, which promises to be ASOR’s biggest ever. Already back in February, we received a record number of paper proposals, and the Programs Committee has worked overtime to put the best of these proposals together into the richest and fullest set of sessions we have ever been able to offer—covering all the major regions of the Near East and wider Mediterranean from earliest times through the Islamic period. -

Naughty & Nice List 2020

North Pole Government, Department of Christmas Affairs | Naughty and Nice List, 2020 North Pole Government NAUGHTY & NICE LIST 2020 1 | © Copyright North Pole Government 2020 christmasaffairs.com NAUGHTY & NICE LIST North Pole Government, Department of Christmas Affairs | Naughty and Nice List, 2020 Naughty and Nice List 2020 This is the Secretary’s This list relates to the people of the world’s performance for 2020 against the measures outlined Naughty and Nice list in the Christmas Behaviour Statements. to the Minister for Christmas Affairs for In addition to providing an alphabetised list of all naughty and nice people for the year 2020, this the year 2020. document contains details of how to rectify a naughty reputation. 2 | © Copyright North Pole Government 2020 christmasaffairs.com North Pole Government, Department of Christmas Affairs | Naughty and Nice List, 2020 Contents About this list 04 Official list (in alphabetical order) 05 Disputes 504 Rehabilitation 505 3 | © Copyright North Pole Government 2020 christmasaffairs.com North Pole Government, Department of Christmas Affairs | Naughty and Nice List, 2020 About this list This list relates to the people of the world’s performance for 2020 against the measures outlined in the Christmas Behaviour Statements. In addition to providing an alphabetised list of all naughty and nice people for the 2020 financial year, this document contains details of how to rectify a naughty reputation. 4 | © Copyright North Pole Government 2020 christmasaffairs.com North Pole Government, Department -

Results Level 5

Pass (P) Level First Name Last Name or Fail (F) 4152 ELEFTHERIA V ACHIRIATI F 4152 ANGELIKI D ACHLADIOTI P 4152 CHRISTINA C ADAMOU F 4152 KONSTANTINOS A ADAMOU P 4152 EVANGELIA S AERAKI P 4152 DIMITRIOS A AFENTOULIS F 4152 ELENI E AFTZALANIDOU P 4152 NIKOLAOS K AGALOS F 4152 EVANGELIA E AGAPITOU P 4152 GEORGIA A AGATSA P 4152 STELIOS E AGGELAKOPOULOS-PREDM F 4152 NIKOLETA A AGGELIDOU F 4152 MIKAELA G AGGELINAKI P 4152 EVAGGELOS N AGGELOPOULOS F 4152 STAMATIA-PANAGIOTA G AGGELOPOULOU P 4152 EFROSINI G AGGELOPOULOU F 4152 CHRISTOS E AGORITSAS P 4152 EYAGGELIA V AGRAFIOTI F 4152 KONSTANTINA ATHANASI A AGRAFIOTI F 4152 CHRISTINA S AGRAGGELOU P 4152 AFRODITI A AGRIMAKI P 4152 GIL-HO N AHN P 4152 ANTONIA S AISIOPOULOU F 4152 ANASTASIA M AIVAZOGLOU P 4152 MARGARITA S AKRITIDOU P 4152 ILIANA G AKRIVI F 4152 MARINA K AKRIVOU P 4152 IOANNIS D ALEKOS P 4152 SOPHIA D ALESTA P 4152 PINELOPI K ALETRI F 4152 MARIA ELENI S ALEVIZOU P 4152 ANASTASIOS N ALEVRAS P 4152 PANAGIOTA K ALEXAKIDOU F 4152 ELLI I ALEXAKOU F 4152 ANASTASIA P ALEXAKOU F 4152 MARIOS-NIKOLAOS P ALEXANDROPOULOS P 4152 SOFIA S ALEXANDROPOULOU F 4152 NIKOLETTA ANNA G ALEXANDROPOULOU F 4152 MAGDALINI A ALEXIOU P 4152 ANNA G ALEXIOU F 4152 EVANTHIA A ALEXIOU F 4152 PAVLOS I ALEXOPOULOS P 4152 DORA I ALMPAGLI F 4152 EVGENIA G ALMPANI F 4152 CHRISTIANA P AMBATZI P 4152 MARIA N AMERIKANOU P 4152 DESPINA G AMPATZOGLOU F 4152 AIKATERINI I ANAGNOSTAKI F 4152 MARIA K ANAGNOSTOU F 4152 KYRIAKI N ANAGNOSTOU P 4152 EVANGELOS N ANAGNOSTOU P 4152 MARIA I ANAGNOU P 4152 CHRYSSI G ANASTASAKI P 4152 EVGENIA