Checkmate: a Chess Program for African-American Male Adolescents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

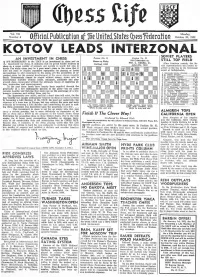

Kolov LEADS INTERZONAL SOVIET PLAYERS an INVESTMENT in CHESS Po~;T;On No

Vol. Vll Monday; N umber 4 Offjeitll Publication of me Unttecl States (bessTederation October 20, 1952 KOlOV LEADS INTERZONAL SOVIET PLAYERS AN INVESTMENT IN CHESS Po~;t;on No. 91 POI;l;"n No. 92 IFE MEMBERSHIP in the USCF is an investment in chess and an Euwe vs. Flohr STILL TOP FIELD L investment for chess. It indicates that its proud holder believes in C.1rIbad, 1932 After fOUl't~n rounds, the S0- chess ns a cause worthy of support, not merely in words but also in viet rcpresentatives still erowd to deeds. For while chess may be a poor man's game in the sense that it gether at the top in the Intel'l'onal does not need or require expensive equipment fm' playing or lavish event at Saltsjobaden. surroundings to add enjoyment to the game, yet the promotion of or· 1. Alexander Kot()v (Russia) .w._.w .... 12-1 ganized chess for the general development of the g'lmc ~ Iway s requires ~: ~ ~~~~(~tu(~~:I;,.i ar ·::::~ ::::::::::~ ~!~t funds. Tournaments cannot be staged without money, teams sent to international matches without funds, collegiate, scholastic and play· ;: t.~h!"'s~~;o il(\~::~~ ry i.. ··::::::::::::ij ); ~.~ ground chess encouraged without the adequate meuns of liupplying ad· 6. Gidcon S tahl ~rc: (Sweden) ...... 81-5l vice, instruction and encouragement. ~: ~,:ct.~.:~bG~~gO~~(t3Ji;Oi· · ·:::: ::::::7i~~ In the past these funds have largely been supplied through the J~: ~~j~hk Elrs'l;~san(A~~;t~~~ ) ::::6i1~ generosity of a few enthusiastic patrons of the game-but no game 11. -

2009 U.S. Tournament.Our.Beginnings

Chess Club and Scholastic Center of Saint Louis Presents the 2009 U.S. Championship Saint Louis, Missouri May 7-17, 2009 History of U.S. Championship “pride and soul of chess,” Paul It has also been a truly national Morphy, was only the fourth true championship. For many years No series of tournaments or chess tournament ever held in the the title tournament was identi- matches enjoys the same rich, world. fied with New York. But it has turbulent history as that of the also been held in towns as small United States Chess Championship. In its first century and a half plus, as South Fallsburg, New York, It is in many ways unique – and, up the United States Championship Mentor, Ohio, and Greenville, to recently, unappreciated. has provided all kinds of entertain- Pennsylvania. ment. It has introduced new In Europe and elsewhere, the idea heroes exactly one hundred years Fans have witnessed of choosing a national champion apart in Paul Morphy (1857) and championship play in Boston, and came slowly. The first Russian Bobby Fischer (1957) and honored Las Vegas, Baltimore and Los championship tournament, for remarkable veterans such as Angeles, Lexington, Kentucky, example, was held in 1889. The Sammy Reshevsky in his late 60s. and El Paso, Texas. The title has Germans did not get around to There have been stunning upsets been decided in sites as varied naming a champion until 1879. (Arnold Denker in 1944 and John as the Sazerac Coffee House in The first official Hungarian champi- Grefe in 1973) and marvelous 1845 to the Cincinnati Literary onship occurred in 1906, and the achievements (Fischer’s winning Club, the Automobile Club of first Dutch, three years later. -

Top 10 Checkmate Pa Erns

GM Miguel Illescas and the Internet Chess Club present: Top 10 Checkmate Pa=erns GM Miguel Illescas doesn't need a presentation, but we're talking about one of the most influential chess players in the last decades, especially in Spain, just to put things in the right perspective. Miguel, so far, has won the Spanish national championship of 1995, 1998, 1999, 2001, 2004, 2005, 2007, and 2010. In team competitions, he has represented his country at many Olympiads, from 1986 onwards, and won an individual bronze medal at Turin in 2006. Miguel won international tournaments too, such as Las Palmas 1987 and 1988, Oviedo 1991, Pamplona 1991/92, 2nd at Leon 1992 (after Boris Gulko), 3rd at Chalkidiki 1992 (after Vladimir Kramnik and Joel Lautier), Lisbon Zonal 1993, and 2nd at Wijk aan Zee 1993 (after Anatoly Karpov). He kept winning during the latter part of the nineties, including Linares (MEX) 1994, Linares (ESP) Zonal 1995, Madrid 1996, and Pamplona 1997/98. Some Palmares! The ultimate goal of a chess player is to checkmate the opponent. We know that – especially at the higher level – it's rare to see someone get checkmated over the board, but when it happens, there is a sense of fulfillment that only a checkmate can give. To learn how to checkmate an opponent is not an easy task, though. Checkmating is probably the only phase of the game that can be associated with mathematics. Maths and checkmating have one crucial thing in common: patterns! GM Miguel is not going to show us a long list of checkmate examples: the series intends to teach patterns. -

Final Report to Fide on Activities of Jersey Chess Club 2019 Further To

Final Report to Fide on activities of Jersey Chess club 2019 Further to our interim report there has been little movement in chess activity in Jersey but we have the following updates; 1 Chess Teacher Training course Paul Wojciechowski attended and passed the course held in London on 2 and 3 December 2019. 2 Schools chess Chess clubs have commenced at Rouge Boiliion School and St Lawrence school and Paul Wojciechowski is assisting in teaching the children at those schools. Each school has approximately 20 participants. 38 Children played in our final tournament of the year held on Sunday 24 November 2019. The numbers were down on the previous years but we anticipate these improving following the starting of clubs in the schools mentioned above Key performance indicators We have attached appendix C updated with comments on what we have achieved against the key performance targets. We are pleased to announce that we have met those targets and look forward to improving chess within our Island In 2020. We have received acceptances from 4 Grand Masters 2 WGMs and $ International Masters for our tournament to be held at 28 March to 4 April and are still looking to invite more Titled players especially WGMs or WIMs. We would appreciate your assistance in finding some of these players. Report to Fide on activities of Jersey Chess club 2019. Polar Capital Jersey International Tournament held on 6th to 13 April 2019 Report on the Polar Capital Jersey International chess Tournament 2019 held at the Ommaroo Hotel 6th to 13th April 2019 The Jersey Open and Holiday tournaments were held at the Ommaroo Hotel on the above dates. -

The Indian Trail Chess Club

The Indian Trail Chess Club Scholastic chess has enjoyed explosive growth in recent years and has shed its reputation as a game only for intellectuals. Beyond the sheer pleasure of playing, studies have shown that chess improves academic performance, concentration, logical thinking, and social skills. The Indian Trail Chess Club will re-open on Wednesday, Sept. 11th and continue until May 13th. The club is open to those in grades K-5 and will meet once a week on Wednesday afternoons from 3:20 pm to 5 pm at Indian Trail, in the small gym/lunchroom. Parents and caregivers will conveniently be able to pick up students using the side door (A3). Club parent volunteer coordinators are Jane Evans and Lara Leaf. Both are long-time Highland Park chess parents whose children are strong players. Eli Elder and Sawyer Harris, two of the strongest high school players on the North Shore, head our coaching staff. Indian Trail Chess Club since opening in 2007 has won 28 team trophies at state championship events. Members are not required to attend every session and may leave early. Attendance will be taken and parents should specify in writing any variations from full-time attendance. (Additional procedures are spelled out in the Club Handbook.) Although members may join the club at any time during the school year, beginners are encouraged to attend regularly during the first few months for introductory lessons. Lessons will run 45 minutes (from 3:45-4:30pm), and members are expected to attend lessons when they are offered. The remainder of each session will be devoted to play. -

A GUIDE to SCHOLASTIC CHESS (11Th Edition Revised June 26, 2021)

A GUIDE TO SCHOLASTIC CHESS (11th Edition Revised June 26, 2021) PREFACE Dear Administrator, Teacher, or Coach This guide was created to help teachers and scholastic chess organizers who wish to begin, improve, or strengthen their school chess program. It covers how to organize a school chess club, run tournaments, keep interest high, and generate administrative, school district, parental and public support. I would like to thank the United States Chess Federation Club Development Committee, especially former Chairman Randy Siebert, for allowing us to use the framework of The Guide to a Successful Chess Club (1985) as a basis for this book. In addition, I want to thank FIDE Master Tom Brownscombe (NV), National Tournament Director, and the United States Chess Federation (US Chess) for their continuing help in the preparation of this publication. Scholastic chess, under the guidance of US Chess, has greatly expanded and made it possible for the wide distribution of this Guide. I look forward to working with them on many projects in the future. The following scholastic organizers reviewed various editions of this work and made many suggestions, which have been included. Thanks go to Jay Blem (CA), Leo Cotter (CA), Stephan Dann (MA), Bob Fischer (IN), Doug Meux (NM), Andy Nowak (NM), Andrew Smith (CA), Brian Bugbee (NY), WIM Beatriz Marinello (NY), WIM Alexey Root (TX), Ernest Schlich (VA), Tim Just (IL), Karis Bellisario and many others too numerous to mention. Finally, a special thanks to my wife, Susan, who has been patient and understanding. Dewain R. Barber Technical Editor: Tim Just (Author of My Opponent is Eating a Doughnut and Just Law; Editor 5th, 6th and 7th editions of the Official Rules of Chess). -

October, 2007

Colorado Chess Informant YOUR COLORADOwww.colorado-chess.com STATE CHESS ASSOCIATION’S Oct 2007 Volume 34 Number 4 ⇒ On the web: http://www.colorado-chess.com Volume 34 Number 4 Oct 2007/$3.00 COLORADO CHESS INFORMANT Inside This Issue Reports: pg(s) Colorado Open 3 Jackson’s Trip to Nationals 11 CSCA Membership Meeting Minutes 22 Front Range League Report 27 Crosstables Colorado Open 3 Membership Meeting Open 10 Pike’s Peak Open 14 Pueblo Open 25 Boulder Invitational/Chess Festival 26 Games The King (of chess) and I 6 Membership Meeting Open Games 12 Pike’s Peak Games 15 The $116.67 Endgame 20 Snow White 24 Departments CSCA Info. 2 Humor 27 Club Directory 28 Colorado Tour Update 29 Tournament announcements 30 Features “How to Play Chess Like an “How to Play Chess Like an Animal” 8 Cutting Off the King 9 “How to Beat Granddad at Checkers” 11 Animal”, written by Shipp’s Log 18 BrianPage Wall 1 and Anthea Carson Colorado Chess Informant www.colorado-chess.com Oct 2007 Volume 34 Number 4 COLORADO STATE Treasurer: The Passed Pawn CHESS ASSOCIATION Richard Buchanan 844B Prospect Place CO Chess Informant Editor The COLORADO STATE Manitou Springs, CO 80829 Randy Reynolds CHESS ASSOCIATION, (719) 685-1984 INC, is a Sec. 501 (C) (3) [email protected] Greetings Chess Friends, tax-exempt, non-profit edu- cational corporation formed Members at Large: Another Colorado Open and to promote chess in Colo- Todd Bardwick CSCA membership meeting rado. Contributions are tax- (303) 770-6696 are in the history books, and deductible. -

The Chess Players

Rollins College Rollins Scholarship Online Master of Liberal Studies Theses 2013 The hesC s Players Gerry A. Wolfson-Grande [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.rollins.edu/mls Part of the Fiction Commons, Leisure Studies Commons, and the Modern Literature Commons Recommended Citation Wolfson-Grande, Gerry A., "The heC ss Players" (2013). Master of Liberal Studies Theses. 38. http://scholarship.rollins.edu/mls/38 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Rollins Scholarship Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Liberal Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of Rollins Scholarship Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Chess Players A Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Liberal Studies by Gerry A. Wolfson-Grande May, 2013 Mentor: Dr. Philip F. Deaver Reader: Dr. Steve Phelan Rollins College Hamilton Holt School Master of Liberal Studies Program Winter Park, Florida The Chess Players By Gerry A. Wolfson-Grande May, 2013 Project Approved: ______________________________________ Mentor ______________________________________ Reader ______________________________________ Director, Master of Liberal Studies Program ______________________________________ Dean, Hamilton Holt School Rollins College Acknowledgments I would like to thank several of my MLS professors for providing the opportunity and encouragement—and in some cases a very long rope—to apply my chosen topic to -

US Chess Membership Rates

US Chess Membership Rates Age Memberships One Year Two Years Senior (age 65 or older at purchase) $40 $77 Adult $45 $87 Young Adult (under age 24 at expiration) $27 $51 Youth (under age 19 at expiration) $20 $37 Family Memberships (1-year) Family Plan #1 (includes parents, their children under age 19 at expiration in the household living at $85 one address, and any full-time college students up to age 24 at expiration) Family Plan #2 (includes all children under age 19 at expiration in the household living at one address) $55 • All memberships expire at the same time. For families wanting to start a new family plan but have at least one current US Chess member, the existing memberships will be pro-rated based on the number of months remaining and the expiration date of the family membership plan will be extended accordingly. Two-Month Membership: $20 • One printed issue of the Chess Life magazine • Only available through affiliates • Not available at US Chess run national events International Online Membership (1-year): $20 • Must live outside the US • Only available through affiliates Life Memberships Life $1500 Senior Life (age 65 or older at purchase) $750 Blind Life (Only available by contacting the US Chess office and showing proof of eligibility. A $375 state’s certification of legal blindness is accepted unless the person holds a valid driver’s license.) Benefactor Life (Benefactor members receive a special membership card, are recognized periodically in Chess Life, the US Chess website, and elsewhere. Any Life member can upgrade to $3000 a benefactor life member.) All life memberships Include a printed copy of the Chess Life magazine each month for free if desired. -

British Chess Championship 2009

September/October 2009 NEWSLETTER OF THE ENGLISH CHESS FEDERATION £1.50 96th BRITISH CHESS CHAMPIONSHIPS 2009 IM Jovanka Houska GM David Howell British Womens Champion 2009 British Champion 2009 and English Womens Champion 2009 & British U21 and U18 Champion 2009 From the Neo-Classical grandeur of St. George’s Hall, Liverpool in 2008, the British Championships returned to the functional modernity of the Riviera International Conference Centre, close to Torquay sea front, for the third time in 12 years. The venue’s popularity can be measured by the response in terms of entries, with almost 1,000 now the norm for Torbay. [continued on Page 5] Editorial It was with great personal sadness that I learned of the death of John Littlewood. I had worked with John for many years, first in his post of Director for Junior Chess and more recently as ECF News a regular writer for ChessMoves. He Nominations for Election at the ECF AGM 2009 sent his last article to me on the day The following candidates have been nominated. Elections will take place at the Annual before he died, which was also the General Meeting on 17th October in London last time I spoke to him. John to me was the kindest and most courteous Post Nominee(s) gentleman, always generous of his President CJ de Mooi John Paines time and help and a colleague who Chief Executive Chris Majer will be sadly missed. Director of Finance Vacant Cynthia Gurney Non-Executive Director Sean Hewitt Alan Martin John Wickham Director of Marketing Stewart Reuben Director of Home Chess Cyril Johnson Adam Raoof Director of International Lawrence Cooper Director of Junior Chess and Education Peter Purland The FIDE Delegate Nigel Short Gerry Walsh The Chairman of the Finance Committee Mike Adams Members of the Finance Committee Alan Martin John Littlewood in action .. -

EUROPEAN INDIVIDUAL WOMEN's CHESS CHAMPIONSHIP 2021 Iasi, Romania, 8 (Arrival) – 21 (Departure) August

EUROPEAN INDIVIDUAL WOMEN’S CHESS CHAMPIONSHIP 2021 Iasi, Romania, 8 (arrival) – 21 (departure) August GENERAL REGULATIONS 1 1. Organizers Romanian Chess Federation and Universul Chess Club, under the auspices of European Chess Union. 2. Venue, Date & Schedule The Championship will be held in Iasi, Romania, from 8th of August (arrival day) until 21st of August (departure day). The playing venue and the accommodation are in UNIREA Hotel**** located in the city of Iasi. Schedule of the tournament is the following: Sunday 8 August Arrival day Monday 9 August 10:00 Technical meeting Monday 9 August 14:30 Opening ceremony Monday 9 August 15:00 Round I Tuesday 10 August 15:00 Round II Wednesady 11 August 15:00 Round III Thursday 12 August 15:00 Round IV Friday 13 August 15:00 Round V Saturday 14 August 15:00 Round VI Sunday 15 August Free day Monday 16 August 15:00 Round VII Tuesady 17 August 15:00 Round VIII Wednesady 18 August 15:00 Round IX Thursday 19 August 15:00 Round X Friday 20 August 14:00 Round XI Friday 20 August 20:30 Awarding ceremony Saturday 21 August Departure day 3. Participation 3.1 The 21st European Individual Chess Championship for women is open for all players representing the Chess Federations members of the European Chess Union, regardless of their title or rating. Applications are to be sent by national federations. There is no limit of participants per federation. By the registration, each player confirms that she will participate in the 21st edition of EIWCC 2021, part of the World Championship Cycle and has acquainted herself with the applicable ECU Tournament Rules and Regulations, FIDE Code of Ethics and ECU & FIDE Anti-Cheating 2 Guidelines and accept the conditions relating to her participation as described in the General Regulations of the Championship. -

Chess Club Eyes Final Checkmate Thehigh School View

March 14, 2019 community B9 The High School View The High School View is staffed and prepared entirely by students from the Martha’s Vineyard Regional High School, and published on their behalf by The Martha’s Vineyard Times, with the generous assistance of the sponsors whose names appear below. as a coach is more to bring a big role, and I know the excitement to their playing. I team benefits.” just love the game.” With one final postseason Chess club eyes final checkmate Coach McCarthy also match to wrap up an already credits his friend and fellow winning season for the team, BY MACKENZIE CONDON tion. As the season progress- played alternating home and passion. “I’m more of Islander, Jim Trish, with be- Coach McCarthy said, “Prac- es, the players of each posi- and away matches every an enthusiast, and there are ing an important mentor for tice during Friday flex blocks he Martha’s Vineyard tion become more consistent. Wednesday against South some kids on the team who the team. “He is an enthusi- doesn’t end after the competi- Regional High School “Fighting for board spots Coast Conference teams. “If T(MVRHS) chess team does create a competitive at- someone is a spring or fall will be playing for the South mosphere in practice that we athlete,” he said, “they can be Coast Conference Chess really look forward to,” said on the chess team in the win- Championship after amassing junior Vito Aiello. ter, because while we practice the most regular-season vic- Coach McCarthy listed all year long, the competition tories in the conference.