Does Gender Responsive Disaster Risk Reduction Make a Difference?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

51042 Vanuatu Tanna FACT SHEET

TRAVEL WITH CHRIS BROWN VANUATU: TANNA VOLCANO When most people think of island getaways, they think of resorts and umbrella drinks... but this week, Chris is headed to an island getaway with a difference. On Vanuatu’s Tanna Island, Chris gets to visit an active volcano but first he needs to get some courage and words of advice from the Chief of a black magic village. Will this be enough to get him to the top of Mt Yasur? And will he make it back to tell his tale? VANUATU FAST FACTS: • Officially named the Republic of Vanuatu. • An island nation located in the South Pacific Ocean. The archipelago, which is of volcanic origin, is some 1,750 kilometres (1,090 mi) east of northern Australia. • Capital City is Port Vila (on the island of Efate) • Local currency: Vatu (VT) • There are over 120 distinct languages and many more dialects in Vanuatu but 3 official languages: English, French and Bislama (pidgin English). • Vanuatu was first inhabited by Melanesian people. TANNA ISLAND ABOUT: • The island is 40 km (25 mi) long and 19 km (12 mi) wide, with a total area of 565 km². • Tanna means ‘earth’ in Tannese. • Tanna is best known as the home to one of Vanuatu’s most popular tourist attractions, the Mount Yasur volcano. Considered one of the world’s safest and most accessible volcanoes, Mt Yasur is just a two hour drive from Tanna’s White Grass Airport followed by a short 15/20 minute walk to the crater rim. • Today Tanna is one of the Islands where culture and custom are still very strong. -

Your Cruise Revealing the Mysteries of Melanesia

Revealing the Mysteries of Melanesia From 2/9/2022 From Nouméa Ship: LE LAPEROUSE to 2/20/2022 to Honiara, Guadalcanal Island PONANT invites you to discover the natural wonders of the Coral Sea in Vanuatu and New Caledonia. From Nouméa to Honiara, you will set sail aboard Le Lapérouse on a 12-day expedition cruise into the heart of the South Pacific to discover ancestral tribes and paradisiacal landscapes. Le Lapérouse will first take you to the sublime islandLifou of with its picture-postcard landscapes of white-sand beaches and tropical vegetation, located in the Loyalty archipelago. Your voyage will continue to Vanuatu, considered by some as the “ happiest country in the world” with its 83 islands, it unfurls a palette of extremely varied landscapes. Active volcanoes, beaches bordered by palm trees, and tropical forests welcome visitors to this exceptional archipelago located in Melanesia. Transfer + flight Honiara/Brisbane In Tanna, do not miss out on exploring the imposing Mount Yasur, considered to be the most accessible active volcano in the world. During your voyage, you will have the opportunity to visit several traditional villages, particularly on the islands of Malekula, Ambrym and Ureparapara. Their inhabitants will be happy to share their customs, notable for singing, dancing and art, with you. Le Lapérouse will also allow you to disembark onto dream beaches. Espiritu Santo, the archipelago’s main island, promises you an unforgettable bathing experience in an idyllic setting. The end of your voyage will be marked by the discovery of the Solomon Islands, a real tropical Eden. The information in this document is valid as of 9/26/2021 Revealing the Mysteries of Melanesia YOUR STOPOVERS : NOUMÉA Embarkation 2/9/2022 from 4:00 PM to 5:00 PM Departure 2/9/2022 at 7:00 PM Perched on a peninsula between bays and hills, on the south-west coast of Grande Terre, Noumea enjoys a magnificent natural setting. -

The Coconut Crab the Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR) Was Established in June 1982 by an Act of the Australian Parliament

The Coconut Crab The Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR) was established in June 1982 by an Act of the Australian Parliament. Its mandate is to help identify agricultural problems in developing countries and to commission collaborative research between Australian and developing country researchers in fields where Australia has a special research competence. Where trade names are used this constitutes neither endorsement of nor discrimination against any product by the Centre. ACIAR Monograph Series This peer-reviewed series contains the results of original research supported by ACIAR, or material deemed relevant to ACIAR's research objectives. The series is distributed internationally, with an emphasis on developing countries. Reprinted 1992 © Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research G.P.O. Box 1571, Canberra, ACT, Australia 2601 Brown, I.W. and Fielder, D .R. 1991. The Coconut Crab: aspects of the biology and ecology of Birgus Zatro in the Republic of Vanuatu. ACIAR Monograph No.8, 136 p. ISBN I 86320 054 I Technical editing: Apword Partners, Canberra Production management: Peter Lynch Design and production: BPD Graphic Associates, Canberra, ACT Printed by: Goanna Print, Fyshwick The Coconut Crab: aspects of the biology and ecology of Birgus latro in the Republic of Vanuatu Editors I.w. Brown and D.R. Fielder Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research, Canberra, Australia 199 1 The Authors I.W. Brown. Queensland Department of Primary Industries, Southern Fisheries Centre, PO Box 76, Deception Bay, Queensland, Australia D.R. Fielder. Department of Zoology, University of Queensland, St Lucia, Queensland, Australia W.J. Fletcher. Western Australian Marine Research Laboratories, PO Box 20, North Beach, Western Australia, Australia S. -

Complex and Cascading Triggering of Submarine Landslides And

ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 13 December 2018 doi: 10.3389/feart.2018.00223 Complex and Cascading Triggering of Submarine Landslides and Turbidity Currents at Volcanic Islands Revealed From Integration of High-Resolution Onshore and Offshore Surveys Michael A. Clare 1*, Tim Le Bas 1, David M. Price 1,2, James E. Hunt 1, David Sear 3, Matthieu J. B. Cartigny 4, Age Vellinga 2, William Symons 2, Christopher Firth 5 and Shane Cronin 6 1 National Oceanography Centre, University of Southampton Waterfront Campus, Southampton, United Kingdom, 2 National Oceanography Centre, School of Ocean and Earth Science, University of Southampton, Southampton, United Kingdom, 3 Department of Geography & Environment, University of Southampton, Southampton, United Kingdom, 4 Department of Geography, Durham University, Durham, United Kingdom, 5 Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Macquarie Edited by: University, Sydney, NSW, Australia, 6 School of Environment, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand Ivar Midtkandal, University of Oslo, Norway Reviewed by: Submerged flanks of volcanic islands are prone to hazards including submarine Gijs Allard Henstra, landslides that may trigger damaging tsunamis and sediment-laden seafloor flows (called University of Bergen, Norway “turbidity currents”). These hazards can break seafloor infrastructure which is critical for Miquel Poyatos Moré, University of Oslo, Norway global communications and energy transmission. Small Island Developing States are *Correspondence: particularly vulnerable to these hazards due to their remote and isolated nature, small size, Michael A. Clare high population densities, and weak economies. Despite their vulnerability, few detailed [email protected] offshore surveys exist for such islands, resulting in a geohazard “blindspot,” particularly in Specialty section: the South Pacific. -

A Case Study in Port Resolution, Tanna Island Vanuatu

Effective Coastal Adaptation Needs Accurate Hazard Assessment : A Case Study In Port Resolution, Tanna Island Vanuatu Faivre Faivre ( [email protected] ) Grith University - Gold Coast Campus https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4122-9819 Rodger Tomlinson Grith University - GC Campus: Grith University - Gold Coast Campus Daniel Ware Grith University - GC Campus: Grith University - Gold Coast Campus Saeed Shaeri CSU: Charles Sturt University Wade Hadwen Grith University - GC Campus: Grith University - Gold Coast Campus Andrew Buckwell Grith University Brendan Mackey Grith University - GC Campus: Grith University - Gold Coast Campus Research Article Keywords: amplied, Small Island Developing States, stabilise, eroding Posted Date: July 14th, 2021 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-648458/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 1/22 Abstract Developing countries face risks from natural hazards that are being amplied by climate change. Selection of effective adaptation interventions to manage these risks requires a suciently accurate assessment of the coastal hazard at a given location. Yet challenges remain in terms of understanding local coastal risks given the coarseness of global wave models and the paucity of locally scaled data in most developing countries, including Small Island Developing States (SIDS) like Vanuatu. The aim of this paper was to examine the differences in hazard assessment and adaptation option selections arising from analyses using globally versus locally scaled data on coastal processes. As a case study, we focused on an eroding cliff face in Port Resolution on Tanna Island, Vanuatu, which is of concern to the local community and government authorities. -

VANUATU – SATELLITE IMAGE DETECTED DAMAGE ESTIMATES Version 1.0 UNOSAT Activation: TC-2015-000023-VUT 20 April 2015 Geneva, Switzerland

VANUATU – SATELLITE IMAGE DETECTED DAMAGE ESTIMATES Version 1.0 UNOSAT Activation: TC-2015-000023-VUT 20 April 2015 Geneva, Switzerland Description On 14 March 2015 tropical cyclone Pam made landfall over the island nation of Vanuatu and caused widespread damage and destruction. The International Charter for Space and Major Disasters was activated on 12 March 2015 by UNITAR/UNOSAT on behalf of UNOCHA. UNITAR/UNOSAT products and geographic datasets are available at http://www.unitar.org/unosat/maps/VUT. The table below provides satellite image detected damage statistics for regions of Vanuatu. Figures are based upon analysis of satellite imagery acquired on 15, 16, 17, 18 and 19 March 2015, as well as data from outside sources such as Open Street Map. It is important to note the presence of limitations in these data sources and that this assessment is not a field survey and should be treated with caution. This document is part of an on-going satellite monitoring program of UNITAR/UNOSAT for the Vanuatu cyclone in support of international humanitarian assistance and created to respond to the needs of UN agencies and their partners. Please send feedback to UNITAR/UNOSAT at the contact information below. Table 1 – UNITAR/UNOSAT Estimated Damage Statistics for Vanuatu Total number Total number of Percentage of potentially Island of buildings buildings within affected buildings in Confidence (Pre-Event) affected zones damaged zones *Ambaé 3,180 800 25% Low Aniwa 90 2 2% Medium Buninga 30 30 100% Medium Efate 18,000 9,000 50% Medium Emae 420 260 62% Medium Epi 3,500 3,000 71% Medium Lamen 260 215 83% High Makura 60 40 67% Medium Pentecost 4,500 650 14% Low *Tanna 14,000 10,500 75% Medium Tongariki 65 50 77% Medium Tongoa 450 350 78% Medium *Erromango 1200 850 70% Medium *Estimate based on a partial analysis. -

The Languages of Vanuatu: Unity and Diversity Alexandre François, Sébastien Lacrampe, Michael Franjieh, Stefan Schnell

The Languages of Vanuatu: Unity and Diversity Alexandre François, Sébastien Lacrampe, Michael Franjieh, Stefan Schnell To cite this version: Alexandre François, Sébastien Lacrampe, Michael Franjieh, Stefan Schnell. The Languages of Vanu- atu: Unity and Diversity. Alexandre François; Sébastien Lacrampe; Michael Franjieh; Stefan Schnell. France. 5, Asia Pacific Linguistics Open Access, 2015, Studies in the Languages of Island Melanesia, 9781922185235. halshs-01186004 HAL Id: halshs-01186004 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01186004 Submitted on 23 Aug 2015 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivatives| 4.0 International License THE LANGUAGES OF VANUATU UNITY AND DIVERSITY Edited by Alexandre François Sébastien Lacrampe Michael Franjieh Stefan Schnell uages o ang f Is L la e nd h t M in e l a Asia-Pacific Linguistics s e n i e ng ge of I d a u a s l L s and the M ni e l a s e s n i e d i u s t a S ~ ~ A s es ia- c P A c u acfi n i i c O pe L n s i g ius itc a -

V07VUGO04 Project Officer

Project Officer - Language & Culture Malakula Kaljorol Senta (MKS) Lakatoro, Malakula Island, Vanuatu 24 months September 2008 - September 2010 The Malakula Kaljorol Senta (Malakula Cultural Centre) MKS is the only provincial branch of the main Vanuatu Cultural Centre based in Port Vila. Situated at the Provincial Centre at Lakatoro, Central Malekula the centre is very important and plays a very important role in preventing and preserving the cultures of the people of Malekula. It was established in 1991 to be the doorway and also, preserve and promote the cultures of Malekula. The main objectives for the Malakula Cultural Centre (MKS) are to: upgrade the custom and cultures of Malekula for the attraction of visitors and interested custom role from Malekula advertise the section headings based on MCC attach with the Vanuatu National Museum. collect and preserve artifacts of historical, customary and cultural importance used and practiced on the island of Malakula provide temperature and humidity control for the audio visual equipment. Tasks carried out by the Malakula Cultural Centre include: Carry out primary and secondary school visits Officer giving talks representing cultures in developing the Malampa REDI (5 years development plan). Page 1 of 4 Give assistance to researchers and other people sent by the Vanuatu Cultural Centre to do work on Malekula. To learn more visit the website at: http://www.vanuatuculture.org/ Need of language documentation and orthography development in communities in Malakula where there are not yet agreed orthographies Development of additional vernacular literacy materials and assistance in training teachers Support the Malakula Kaljoral Senta in the development of work plans and long-term plans Literacy manuals developed Establishment of vernacular literacy programs in Grade 1 in as many schools as possible in the Malampa province as per the Ministry of Education policy. -

South Malekula Area Council; Malampa Province

V-CAP site: South Malekula Area Council, Malampa Province South Malekula Area Council; Malampa Province 1 V-CAP site context and background Malampa is one of the six provinces of Vanuatu, located in the centre of the country and consisting of three main islands namely Malekula, Ambrym and Paama. It also includes a number of smaller offshore islands – the small islands of Uripiv, Norsup, Rano, Wala, Atchin and Vao off the coast of Malekula and the volcanic island of Lopevi near Paama (currently uninhabited). Also included are the Maskelynne Islands and other small islands suck as Akam and Avock along the south coast of Malekula. The total population of Malampa Province is 36,722 (2009 census) people and it contains an area of 2,779 km². Malekula is the most populated and developed island in the province and houses the provincial capital named Lakatoro. Malekula receives an abundance of precipitation. The temperature on the island varies during the hot and cold seasons, but averages approximately 24.9°C at the coast and is a few degrees cooler in the centre of the island. Weather in Malekula is seasonal, and warmer from November until April and cooler and dryer period typically from May to October. Like the rest of Vanuatu, the island’s weather is strongly influenced by the El Nino Southern Oscillation cycles. During the El Nino (warm phase) the country is subject to long dry spells. During the La Nina (cool phase) Vanuatu has prolonged wet conditions. Malekula is located on active geological faults. The southeastern side of the island experienced major earthquakes as recently as the 1990s and the land, e.g. -

Download 15.55 MB

Social Safeguards Due Diligence Report May 2021 Vanuatu: Interisland Shipping Support Project (Construction and Rehabilitation of Selected Domestic Wharves) Prepared by the Ministry of Infrastructure and Public Utilities for the Republic of Vanuatu and the Asian Development Bank. This social safeguards due diligence report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Updated Social Safeguards Due Diligence Report May 2021 VAN: Vanuatu Interisland Shipping Support Project (Construction and Rehabilitation of Selected Domestic Wharves) Prepared By: Ministry of Infrastructure and Public Utilities (MIPU), Government of Vanuatu for the Asian Development Bank, Republic of Vanuatu, Vanuatu Interisland Shipping Project Prepared For: Ministry of Finance and Economic Management (MEFM) – the Executing Agency, Ministry of Infrastructure and Public Utilities (MIPU) – Implementing Agency, Public Works Department – Implementing Agency This report may not be amended or used by any person other than by the MIPU’s expressed permission. In any event MIPU accepts no liability for any costs, liabilities or losses arising as a result of the use of or reliance of the contents of this report by any person other than MIPU and the project donor agencies, the Asian Development Bank, and NZ MFAT. -

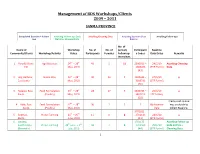

Management of BDS Workshops/Clients 2009 – 2011

Management of BDS Workshops/Clients 2009 – 2011 SANMA PROVINCE Completed Baseline + Follow Awaiting Follow ups Data Awaiting Cleaning Data Awaiting Baseline Data Awaiting Follow ups ups Entries+ Cleaning Data Entries. No. of Name of Workshop No. of No. of (actual) Participant Baseline Community/Clients Workshop/Activity Dates Participants Females Follow up s Codes Data Dates Remarks Interviews. 1. Fanafo/Stone Agri Business 24th – 28th 43 5 11 230001S – 24/5/10 Awaiting Cleaning Hill May, 2010 230043S (ETF Forms) Data. (43) 2. Hog Harbour, Home Stay 24th – 28th 30 22 7 330044S – 27/5/10 ↓ East Santo May, 2010 330073S (ETF Forms) (30) 3. Natawa, East Feed Formulation 25th – 28th 28 17 7 340074S – 25/5/10 ↓ Santo (Poultry) May, 2010 340101S ETF Forms) (28) Fremy said no one 4. Kole, East Feed Formulation 27th – 28th 30 ? ? ? No Baseline was available to Santo (Poultry) May, 2010 data collect Baseline. 370102S – 5. Bodmas, Prawn Farming 21st – 25th 11 0 2 370112S 24/6/10 ↓ Santo June, 2010 (11) (ETF Forms) 6. Ipayato, 370113S – Awaiting Follow up South Santo Prawn Farming 28th June – 2nd 44 7 6 370156S 29/6/10 Data entries + (Kerevalis) July, 2010 (44) (ETF Forms) Cleaning Data. 1 17th – 18th 7. Malo Plantation June, 2010 12 ? ? ? No Baseline MEO not aware of Management data this training. Awaiting Follow up 8. Tassiriki, Agri Business 27th Sept. – 1st 33 18 3 580157S – 30/9/10 Data entries + South Santo Oct. 2010 580189S Cleaning Data. (33) 9. Port Orly, East Food Preparation 13th – 19th 23 20 5 610190S – 15/9/10 Awaiting Cleaning Santo Sept. -

Tanna Island - Wikipedia

Tanna Island - Wikipedia Not logged in Talk Contributions Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View history Tanna Island From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Coordinates : 19°30′S 169°20′E Tanna (also spelled Tana) is an island in Tafea Main page Tanna Contents Province of Vanuatu. Current events Random article Contents [hide] About Wikipedia 1 Geography Contact us 2 History Donate 3 Culture and economy 3.1 Population Contribute 3.2 John Frum movement Help 3.3 Language Learn to edit 3.4 Economy Community portal 4 Cultural references Recent changes Upload file 5 Transportation 6 References Tools 7 Filmography Tanna and the nearby island of Aniwa What links here 8 External links Related changes Special pages Permanent link Geography [ edit ] Page information It is 40 kilometres (25 miles) long and 19 Cite this page Wikidata item kilometres (12 miles) wide, with a total area of 550 square kilometres (212 square miles). Its Print/export highest point is the 1,084-metre (3,556-foot) Download as PDF summit of Mount Tukosmera in the south of the Geography Printable version island. Location South Pacific Ocean Coordinates 19°30′S 169°20′E In other projects Siwi Lake was located in the east, northeast of Archipelago Vanuatu Wikimedia Commons the peak, close to the coast until mid-April 2000 2 Wikivoyage when following unusually heavy rain, the lake Area 550 km (210 sq mi) burst down the valley into Sulphur Bay, Length 40 km (25 mi) Languages destroying the village with no loss of life. Mount Width 19 km (11.8 mi) Bislama Yasur is an accessible active volcano which is Highest elevation 1,084 m (3,556 ft) Български located on the southeast coast.