FAR from HOME: Printing Under Extraordinary Circumstances 1917–1963

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dalmatia Tourist Guide

Vuk Tvrtko Opa~i}: County of Split and Dalmatia . 4 Tourist Review: Publisher: GRAPHIS d.o.o. Maksimirska 88, Zagreb Tel./faks: (385 1) 2322-975 E-mail: [email protected] Editor-in-Chief: Elizabeta [unde Ivo Babi}: Editorial Committee: Zvonko Ben~i}, Smiljana [unde, Split in Emperor Diocletian's Palace . 6 Marilka Krajnovi}, Silvana Jaku{, fra Gabriel Juri{i}, Ton~i ^ori} Editorial Council: Mili Razovi}, Bo`o Sin~i}, Ivica Kova~evi}, Stjepanka Mar~i}, Ivo Babi}: Davor Glavina The historical heart of Trogir and its Art Director: Elizabeta [unde cathedral . 9 Photography Editor: Goran Morovi} Logo Design: @eljko Kozari} Layout and Proofing: GRAPHIS Language Editor: Marilka Krajnovi} Printed in: Croatian, English, Czech, and Gvido Piasevoli: German Pearls of central Dalmatia . 12 Translators: German – Irena Bad`ek-Zub~i} English – Katarina Bijeli}-Beti Czech – Alen Novosad Tourist Map: Ton~i ^ori} Printed by: Tiskara Mei}, Zagreb Cover page: Hvar Port, by Ivo Pervan Ivna Bu}an: Biblical Garden of Stomorija . 15 Published: annually This Review is sponsored by the Tourist Board of the County of Split and Dalmatia For the Tourist Board: Mili Razovi}, Director Prilaz bra}e Kaliterna 10, 21000 Split Gvido Piasevoli: Tel./faks: (385 21) 490-032, 490-033, 490-036 One flew over the tourists' nest . 18 Web: www.dalmacija.net E-mail: [email protected] We would like to thank to all our associates, tourist boards, hotels, and tourist agencies for cooperation. @eljko Kuluz: All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be used or repro- Fishing and fish stories . -

62 February 2019

THE FRONT PAGE KOREA-COLD WAR SEND TO: FAMILIES OF THE MISSING 12 CLIFFORD DRIVE FARMINGDALE, NY 11735 http://www.koreacoldwar.org FebruauryAug 2017 2019 IssueIssue ##6256 POW-MIAPOW-MIA WEWE Remember!Remember! 2017 TENTATIVE2019 FAMILY FAMILY UPDATE UPDATE SCHEDULE*SCHEDULE August 10January-11, 2017 26 Korean Birmingham, Cold War AL Annual, • February DC September 23 San Jose, 9, 2017 CA Detroit, MI – November 4,March 2017 23Boise. San ID Antonio,, January TX 20, • April2018 San27 Salt Diego, Lake Ca City, – February UT 24, 2018, Fort Myers, FLMay – March 18 Omaha, 24, 2018, NE •El September Paso TX. – 07April Dayton, 22, 2018, OH Rapid City, SD CContactontact your your Congressional Congressional Rep Repss through through thethe U.S. Capitol Switchboard - 1-202-224- 3121Capital or Switchboard House Cloak - Room1-202-224-3121 at 1-202- or PLEREMINDERASE NOTE OUR NEW 225House-7350 Cloak (R) andRoom 1-202 at 1-202--225-7330 225-7350 (D) (R) and 1-202-225-7330 (D) ADDRESS Congressional Contacts: http://congCongressionalress.org/congressorg/home/ Contacts: ThankIt’s time you toto renew the many your membersmembership. UShttp://congress.org/congressorg/home/ Senate: http://www.senate.gov/ House:US Senate: http://www.house.gov/ http://www.senate.gov/ that sentHelp their us continue2019 membership our work. WhiteHouse: House: http://www.house.gov/ http://www.whitehouse.gov Please note our new address renewal checks in. White House: http://www.whitehouse.gov Korea Cold War Families of the Please send yourMissin checkg if you 12 Clifford Drive, BoardBoard of ofDirectors Directors and and Staff Staff haven’t sent one in already. -

May/Jun 2002 Graybeards

Staff Officers The Graybeards Presidential Envoy to UN Forces: Kathleen Wyosnick The Magazine for Members, Veterans of the Korean War, and service in Korea. P.O. Box 3716, Saratoga, CA 95070 The Graybeards is the official publication of the Korean War Veterans Association, PH: 408-253-3068 FAX: 408-973-8449 PO Box, 10806, Arlington, VA 22210, (www.kwva.org) and is published six times per year. Judge Advocate and Legal Advisor: Sherman Pratt 1512 S. 20th St., Arlington, VA 22202 EDITOR Vincent A. Krepps PH: 703-521-7706 24 Goucher Woods Ct. Towson, MD 21286-5655 PH: 410-828-8978 FAX: 410-828-7953 Washington, DC Affairs: Blair Cross E-MAIL: [email protected] 904B Martel Ct., Bel Air, MD 21014 MEMBERSHIP Nancy Monson PH: 410-893-8145 PO Box 10806, Arlington, VA 22210 National Chaplain: Irvin L. Sharp, PH: 703-522-9629 16317 Ramond, Maple Hights, OH 44137 PUBLISHER Finisterre Publishing Incorporated PH: 216-475-3121 PO Box 70346, Beaufort, SC 29902 E-MAIL: [email protected] Korean Ex-POW Association: Ernie Contrearas, President National KWVA Headquarters 7931 Quitman Street, Westminister, CO 80030 PH:: 303-428-3368 PRESIDENT Harley J. Coon 4120 Industrial Lane, Beavercreek, OH 45430 National VA/VS Representative: Michael Mahoney PH: 937-426-5105 or FAX: 937-426-4551 582 Wiltshire Rd., Columbus, OH 43204 E-MAIL: [email protected] PH: 614-279-1901 FAX: 614-276-1628 Office Hours: 9am to 5 pm (EST) Mon.–Fri. E-MAIL: [email protected] National Officers Liaison for Canada: Bill Coe 1st VICE PRESIDENT (Vacant) 59 Lenox Ave., Cohoes, N.Y.12047 PH: 518-235-0194 2nd VICE PRESIDENT Dorothy “Dot” Schilling Korean Advisor to the President: Myong Chol Lee 6205 Hwy V, Caledonia, WI 53108 1005 Arborely Court, Mt. -

The Turkish Republic's Jihad? Religious Symbols, Terminology and Ceremonies in Turkey During the Korean War 1950–1953

Middle Eastern Studies ISSN: 0026-3206 (Print) 1743-7881 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fmes20 The Turkish Republic's Jihad? Religious symbols, terminology and ceremonies in Turkey during the Korean War 1950–1953 Nadav Solomonovich To cite this article: Nadav Solomonovich (2018): The Turkish Republic's Jihad? Religious symbols, terminology and ceremonies in Turkey during the Korean War 1950–1953, Middle Eastern Studies To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/00263206.2018.1448273 Published online: 27 Mar 2018. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=fmes20 MIDDLE EASTERN STUDIES, 2018 https://doi.org/10.1080/00263206.2018.1448273 The Turkish Republic’s Jihad? Religious symbols, terminology and ceremonies in Turkey during the Korean War 1950–1953 Nadav Solomonovich Department of Islamic and Middle-Eastern Studies, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Jerusalem, Israel On 25 June 1950, thousands of troops from the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (or North Korea) crossed the 38th parallel latitude and invaded the Republic of Korea (or South Korea). The United Nations (UN), led by the United States, reacted quickly and passed resolution 82, which called for North Korea’s withdrawal. Two days later, the UN Security Council passed resolution 83, calling on UN members to assist South Korea.1 As a result, 16 countries eventually sent troops to -

Stanovanja Po Vrsti, Površina Stanovanj, Število Gospodinjstev In

SLOVENIJA 1-2. STANOVI PREMA VRSTI, POVRŠINA STANOVA, BROJ DOMA6INSTAVA I LICA Broj stinovi prsmi vrsti Stanovi u društvenoj svojini Broj Povröna doma7instava 1-sobni stanova u m' u stanovima površina broj lici ukupno posebne sobe 2-sotmi broj stanova i garsonijere u stanovima stanova u m: u stanovima SOCIJALISTI<KA REPUBLIKA SLOVENIJA AJDOVŠ<INA AJDOV5CINA 1 186 56 376 333 182 70 159 256 * 166 5 86 30 11* 2 029 RATUJE 87 1 25 31 2* 6 625 90 337 7 *61 23 BELA T 2 5 635 7 33 BRJE 114 10 *6 7 88* 121 *36 35* 21 BUDANJE 16* 30 61 10 *66 157 676 *76 19 CESTA 69 6 26 25 5 683 80 332 COL HO 22 ** 33 7 766 112 *02 215 22 CRNICE 11* 1* 29 36 8 597 118 • 01 31* 15 DOBRAVLJE IIS 11 *6 *0 7 856 123 *50 198 11 OOLENJE 29 9 8 2 1*6 29 11* OOLCA POLJANA 71 11 37 18 5 677 7* 285 399 ?6 OUPLJE *7 2 22 22 3 807 *7 201 116 I ERZELJ 25 2 9 11 1 895 2* 82 GABRJE 73 U 32 * 6*3 71 219 80 GOCE 8» 12 36 6 825 80 283 *5 GOJACE 70 8 15 5 65* 66 256 BOU 25 1 11 2 189 28 12* GRADIŠ6E PRI VIPAVI 5* 5 2* 21 * **7 60 226 GRIVCE 17 8 * 1 081 17 6* KANNJE 10* 51 32 6 8*7 109 **0 KOVK *0 5 13 3 079 *1 190 KRUNA GORA 12 1 7 955 13 58 LOKAVEC 2** 31 78 85 15 *ll 251 1 025 161 16 LOZICI 5B 18 2* * 7*5 55 22* 23* 12 LOZE 57 23 18 * 693 58 2*7 201 15 DALE ZABIJE 8* 39 5 975 79 328 HALO POLJE 3* U 2 673 35 181 MANCE 29 9 8 2 320 29 106 NANOS 1 * 80* * 1* OREHOVI CA 1* 19 2 831 *1 179 OTLICA 103 *5 30 6 619 • 37 19 PLACE *7 20 13 3 285 19* PLANINA 101 12 25 38 8 *39 1C6 *86 160 6 POOBREG *2 9 15 1* 2 73* *2 19* 73 POOGRIC 17 2 6 5 1 0*5 16 59 POOKRAJ 110 16 *3 37 7 *3* 111 *36 -

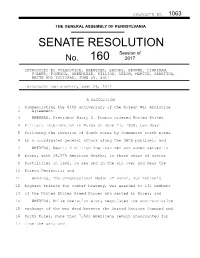

SENATE RESOLUTION Session of No

PRINTER'S NO. 1063 THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY OF PENNSYLVANIA SENATE RESOLUTION Session of No. 160 2017 INTRODUCED BY VULAKOVICH, BREWSTER, BROOKS, BROWNE, DINNIMAN, FOLMER, FONTANA, GREENLEAF, KILLION, LEACH, MARTIN, SABATINA, WHITE AND YUDICHAK, JUNE 29, 2017 INTRODUCED AND ADOPTED, JUNE 29, 2017 A RESOLUTION 1 Commemorating the 64th anniversary of the Korean War Armistice 2 Agreement. 3 WHEREAS, President Harry S. Truman ordered United States 4 military intervention in Korea on June 27, 1950, two days 5 following the invasion of South Korea by Communist North Korea 6 in a coordinated general attack along the 38th parallel; and 7 WHEREAS, Nearly 2 million American men and women served in 8 Korea, with 36,576 American deaths, in three years of active 9 hostilities on land, on sea and in the air over and near the 10 Korean Peninsula; and 11 WHEREAS, The Congressional Medal of Honor, our nation's 12 highest tribute for combat bravery, was awarded to 131 members 13 of the United States Armed Forces who served in Korea; and 14 WHEREAS, While Operation Glory negotiated the post-armistice 15 exchange of the war dead between the United Nations Command and 16 North Korea, more than 7,500 Americans remain unaccounted for 17 from the war; and 1 WHEREAS, The Korean War Armistice Agreement, negotiated for 2 more than two years and signed on July 27, 1953, left the Korean 3 Peninsula divided at the 38th parallel much as it had been since 4 the close of World War II; and 5 WHEREAS, In announcing the armistice to the American people, 6 President Dwight Eisenhower remarked: 7 Soldiers, sailors and airmen of sixteen different 8 countries have stood as partners beside us throughout 9 these long and bitter months. -

Australian Veterans of the Korean War

1 In Memoriam Dr John Bradley MBBS MRACP MD MRACR FRCR FRACR FRACP, Returned & Services League of Australia Limited, who contributed significantly to the commencement and development of the study, but did not live to see the results of his endeavours. Acknowledgments The Department of Veterans’ Affairs and the study team in particular are grateful to: the members of the Study Scientific Advisory Committee for their guidance; the Australian Electoral Commission; the staff at the Australian Institute of Health & Welfare who ascertained the causes of death and compared the death rates of Korean War veterans with the Australian population; and the staff at the Health Insurance Commission who also did data matching. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication data Suggested citation Harrex WK, Horsley KW, Jelfs P, van der Hoek R, Wilson EJ. Mortality of Korean War veterans: the veteran cohort study. A report of the 2002 retrospective cohort study of Australian veterans of the Korean War. Canberra: Department of Veterans’ Affairs, 2003. © Commonwealth of Australia 2003 This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission from the Department of Veterans’ Affairs. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be directed to the Department of Veterans’ Affairs, PO Box 21, Woden ACT 2606 Produced by the Department of Veterans’ Affairs, Canberra ISBN 1 920720 07 3 Publication number: P977 REPATRIATION COMMISSION 21 November 2003 The Hon Danna Vale MP Minister for Veterans’ Affairs Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Dear Minister I have pleasure in submitting the final report of the Mortality Study of Australian Veterans of the Korean War. -

Fault Lines: Sinai Peninsula 20 OCT 2017 the Sinai Peninsula Is a Complicated Operational Environment (OE)

Fault Lines: Sinai Peninsula 20 OCT 2017 The Sinai Peninsula is a complicated operational environment (OE). At present, there are a number of interconnected conditions creating instability and fostering a favorable environment for the growth of Islamic extremist groups. Egypt is battling this situation with large-scale security operations, yet militant activity is not diminishing. The Egyptian government, in coordination with the Israeli government, is placing renewed interest on countering insurgent actors in the region and establishing a lasting security. Despite its best effort, Egypt has been largely unsuccessful. A variety of factors have contributed to the continued rise of the insurgents. We submit there are four key fault lines contributing to instability. These fault lines are neither mutually exclusive nor are they isolated to the Sinai. In fact, they are inexorably intertwined, in ways between Egypt, Israel, and the Sinai Peninsula. Issues related to faults create stability complications, legitimacy concerns, and disidentification problems that can be easily exploited by interested actors. It is essential to understand the conditions creating the faults, the escalation that results from them operating at the same time, and the potential effects for continued insecurity and ultimately instability in the region. FAULT LINES Egypt-Israel Relations - Enduring geopolitical tension between Egypt and Israel, and complex coordination needs between are “exploitable dissimilar and traditionally untrusting cultures, has potential for explosive effects on regional stability. sources of Political Instability - Continued political instability, generated from leadership turmoil, mounting security concerns, and insufficient efforts for economic development may lead to an exponentially dire security situation and direct and violent instability in the challenges to the government. -

Milko Kelemen: Life and Selected Works for Violoncello

MILKO KELEMEN: LIFE AND SELECTED WORKS FOR VIOLONCELLO by JOSIP PETRAČ (Under the Direction of David Starkweather) ABSTRACT Milko Kelemen (b. 1924) is one of the most extraordinary Croatian composers of the post-World War II era. He has received numerous prestigious awards for his work, while his compositions are published by major companies, including Schott, Universal, Peters, and Hans Sikorski editions. His music is little studied or known internationally. This paper examines this innovative, avant-garde musician and sheds light both on Kelemen’s life and his compositional technique. The latter is examined in four compositions featuring cello as the main subject: Changeant (1968), Drammatico (1983), Requiem for Sarajevo (1994), and Musica Amorosa (2004). The examination of these compositions is placed in a biographical context which reveals how Kelemen’s keen political and cultural interests influenced his development as a composer. In particular, this document looks at Kelemen’s role as one of the founders, and the first president, of the Zagreb Music Biennale Festival, an event known for its ground-breaking work in bringing together artists and composers from the eastern and western blocs during the Cold War, as well as revitalising Croatia’s old-fashioned and provincial cultural scene. This festival of avant-garde music has been running since 1961. INDEX WORDS: Milko Kelemen, Zagreb Biennale, cello, avant-garde music, Changeant, Drammatico, Requiem for Sarajevo, Musica Amorosa MILKO KELEMEN:LIFE AND SELECTED WORKS FOR CELLO by JOSIP -

Industrial Framework of Russia. the 250 Largest Industrial Centers Of

INDUSTRIAL FRAMEWORK OF RUSSIA 250 LARGEST INDUSTRIAL CENTERS OF RUSSIA Metodology of the Ranking. Data collection INDUSTRIAL FRAMEWORK OF RUSSIA The ranking is based on the municipal statistics published by the Federal State Statistics Service on the official website1. Basic indicator is Shipment of The 250 Largest Industrial Centers of own production goods, works performed and services rendered related to mining and manufacturing in 2010. The revenue in electricity, gas and water Russia production and supply was taken into account only regarding major power plants which belong to major generation companies of the wholesale electricity market. Therefore, the financial results of urban utilities and other About the Ranking public services are not taken into account in the industrial ranking. The aim of the ranking is to observe the most significant industrial centers in Spatial analysis regarding the allocation of business (productive) assets of the Russia which play the major role in the national economy and create the leading Russian and multinational companies2 was performed. Integrated basis for national welfare. Spatial allocation, sectorial and corporate rankings and company reports was analyzed. That is why with the help of the structure of the 250 Largest Industrial Centers determine “growing points” ranking one could follow relationship between welfare of a city and activities and “depression areas” on the map of Russia. The ranking allows evaluation of large enterprises. Regarding financial results of basic enterprises some of the role of primary production sector at the local level, comparison of the statistical data was adjusted, for example in case an enterprise is related to a importance of large enterprises and medium business in the structure of city but it is located outside of the city border. -

International Organizations and Globalizations of Russian Regions

International Organizations and Globalization of Russian Regions Introduction Why is it so important to raise the issue of globalization for Russia and her regions? Despite the underdevelopment of Russia’s version of globalization, the international community in general and specific foreign countries in particular do have their impact on internal developments in Russia. Sometimes the effects of globalization are not visible enough, but they cannot be disregarded. In spite of his inward-oriented rhetoric, President Putin’s federal reform launched in May 2000 to some extent was inspired by developments outside Russia. These were the foreign investors who were confused by the tug-of-war between the federal center and the regions, and who called for a reshuffle of the federal system in Russia to avoid conflicts between federal and regional laws and get rid of regional autarchy. What is also telling is that Putin intends to implement his federal reform in accordance with formal democratic procedures, keeping in mind Western sensitivity to these issues. The shift of power from the center to the regional actors was the major development in Russian politics in the beginning of the 1990s. Yet the Russian regions are not equal players on the international scene. Not all of them are capable of playing meaningful roles internationally, and these roles can be quite different for each one. Three groups of constituent parts of the Federation ought to be considered as the most important Russian sub-national actors in the international arena. The first group comprises those regions with a strong export potential (industrial regions or those rich in mineral resources[1]). -

Russian Art, Icons + Antiques

RUSSIAN ART, ICONS + ANTIQUES International auction 872 1401 - 1580 RUSSIAN ART, ICONS + ANTIQUES Including The Commercial Attaché Richard Zeiner-Henriksen Russian Collection International auction 872 AUCTION Friday 9 June 2017, 2 pm PREVIEW Wednesday 24 May 3 pm - 6 pm Thursday 25 May Public Holiday Friday 26 May 11 am - 5 pm Saturday 27 May 11 am - 4 pm Sunday 28 May 11 am - 4 pm Monday 29 May 11 am - 5 pm or by appointment Bredgade 33 · DK-1260 Copenhagen K · Tel +45 8818 1111 · Fax +45 8818 1112 [email protected] · bruun-rasmussen.com 872_russisk_s001-188.indd 1 28/04/17 16.28 Коллекция коммерческого атташе Ричарда Зейнера-Хенриксена и другие русские шедевры В течение 19 века Россия переживала стремительную трансформацию - бушевала индустриализация, модернизировалось сельское хозяйство, расширялась инфраструктура и создавалась обширная телеграфная система. Это представило новые возможности для международных деловых отношений, и известные компании, такие как датская Бурмэйстер энд Вэйн (В&W), Восточно-Азиатская Компания (EAC) и Компания Грэйт Норсерн Телеграф (GNT) открыли офисы в России и внесли свой вклад в развитие страны. Большое количество скандинавов выехало на Восток в поисках своей удачи в растущей деловой жизни и промышленности России. Среди многочисленных путешественников возникало сильное увлечение культурой страны, что привело к созданию высококачественных коллекций русского искусства. Именно по этой причине сегодня в Скандинавии так много предметов русского антиквариата, некоторые из которых будут выставлены на этом аукционе. Самые значимые из них будут ещё до аукциона выставлены в посольстве Дании в Лондоне во время «Недели Русского Искусства». Для более подробной информации смотри страницу 9. Изюминкой аукциона, без сомнения, станет Русская коллекция Ричарда Зейнера-Хенриксена, норвежского коммерческого атташе.