Respectability Politics, Armed Self- Defense, and Gender Dynamics in the Milwaukee NAACP Youth Council, 1958-1968

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Direct Action and the Struggle for Integration Mulford Q

Hastings Law Journal Volume 16 | Issue 3 Article 3 1-1965 Direct Action and the Struggle for Integration Mulford Q. Sibley Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Mulford Q. Sibley, Direct Action and the Struggle for Integration, 16 Hastings L.J. 351 (1965). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal/vol16/iss3/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. Direct Action and the Struggle for Integration By MuLorm Q. Smri.y* A MOST striking aspect of the integration struggle in the United States is the role of non-violent direct action. To an extent unsurpassed in history,1 men's attentions have been directed to techniques which astonish, perturb, and sometimes antagonize those familiar only with the more common and orthodox modes of social conflict. Because non- violent direct action is so often misunderstood, it should be seen against a broad background. The civil rights struggle, to be sure, is central. But we shall examine that struggle in the light of general history and the over-all theory of non-violent resistance. Thus we begin by noting the role of non-violent direct action in human thought and experience. We then turn to its part in the American tradition, par- ticularly in the battle for race equality; examine its theory and illus- trate it in twentieth-century experience; inquire into its legitimacy and efficacy; raise several questions crucial to the problem of civil disobedience, which is one of its expressions; and assess its role in the future battle for equality and integration. -

Neutrality Or Engagement?

LESSON 12 Neutrality or Engagement? Goals Students analyze a political cartoon and a diary entry that highlight the risks taken by civil rights workers in the 1960s. They imagine themselves in similar situations and consider conflicting motivations and responsi- bilities. Then they evaluate how much they would sacrifice for an ideal. Central Questions Many Black Mississippians—including Black ministers, teachers, and business owners—chose not to get involved in the Civil Rights Movement because of the dangers connected with participating. What do you think you would have done when Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) or Congress of Ra- cial Equality (CORE) came to your town? Was joining the movement worth the risk? Background Information Many people willingly put their lives and safety on the line to fight for civil rights. But other people chose not to get involved from fear of being punished by the police, employers, or terrorist groups. The dangers were very real: during the 1964 Freedom Summer, there were at least six murders, 29 shootings, 50 fire-bombings, more than 60 beatings, and over 400 arrests in Mississippi. Despite their fears, 80,000 residents, mostly African Americans, risked harassment and intimidation to cast ballots in the Freedom Vote of November 1963. But the next year, during 1964’s Freedom Summer, only 16,000 black Mississippians tried to register to vote in the official election that fall. “The people are scared,” James Forman of SNCC told a reporter. “They tell us, ‘All right. I’ll go down to register [to vote], but what you going to do for me when I lose my job and they beat my head?’” We hear many stories about courage and heroism, but not many about people who didn’t dare to get involved. -

Editorial Contest Winners for 2019 2019

EDITORIAL CONTEST WINNERS FOR 2019 2019 North Carolina Press Association Fighting for your right to know since 1873 2019-ed-tab48_021620.indd 1 2/5/20 1:55 PM 2019 WILLIAM C. LASSITER AWARD HUGH MORTON PHOTOGRAPHER OF THE YEAR SINCE 1988, THIS ANNUAL AWARD HAS GONE TO FIRST AMENDMENT PROPONENTS IN MANY WALKS OF LIFE. SOME OF THE PAST WINNERS INCLUDE CONGRESSIONAL REPRESENTATIVES, STATE LAWMAKERS, PROFESSORS, LAWYERS. Community Newspaper Winner MICHAEL PAUL State Port Pilot This special award was named in honor of the late William C. Lassiter, a former NCPA general counsel and recognizes members of the public who have made significant contributions in support of open government. STEPHEN M. ROSS North Carolina State Representative - (R) North Carolina House District 63 Alamance County Rep. Stephen Ross, 4 term House member run a local bill removing legal notices from General Assembly is his unfailing willingness from Alamance County, former Mayor of newspapers.. And as Chairman of the House to challenge positions held by the League of Burlington and former Alamance County Local Government Committee in 2014, Ross Municipalities and the County Commissioners Commissioner, is awarded the NCPA’s Lassiter stopped a bill that would have changed all Association, of which he is a former member. Award. carriers into newspaper employees, subjecting publishers to worker’s compensation insurance Tonight we honor Rep. Ross for his commitment Steve has been a strong advocate for free liability (for individuals who have historically to an open government and the public’s press rights in everything from battles to been independent contractors) that could have right to know. -

Performative Citizenship in the Civil Rights and Immigrant Rights Movements

Performative Citizenship in the Civil Rights and Immigrant Rights Movements Kathryn Abrams In August 2013, Maria Teresa Kumar, the executive director of Voto Lat mo, spoke aJongside civil rights leaders at the fiftieth anniversary of the March on Washington. A month earlier, immigrant activists invited the Reverend Al Sharpton to join a press conference outside the federal court building as they celebrated a legal victory over joe Arpaio, the anti-immigrant sheriff of Maricopa County. Undocumented youth orga nizing for immigration reform explained their persistence with Marlin Luther King's statement that "the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towardjustice." 1 The civil rights movement remains a potent reminder that politically marginalized groups can shape the Jaw through mobilization and col lective action. This has made the movement a crucial source of sym bolism for those activists who have come after. But it has also been a source of what sociologist Doug McAdam has called "cultural innova uons"2: transformative strategies and tactics that can be embraced and modified by later movements. This chapter examines the legacy of the Civil Rights Act by revisiting the social movement that produced it and comparing that movement to a recent and galvanizing successor, the movement for immigrant rights.3 This movement has not simply used the storied tactics of the civil rights movement; it has modified them 2 A Nation of Widening Opportunities in ways that render them more performative: undocumented activists implement the familiar tactics that enact, in daring and surprising ways, the public belonging to which they aspire.4 This performative dimen sion would seem to distinguish the immigrant rights movement, at the level of organizational strategy, from its civil rights counterpart, whose participants were constitutionally acknowledged as citizens. -

The Crusader Monthll,J Nelijsletter

THE CRUSADER MONTHLL,J NELIJSLETTER ROBERT F. WILLIAMS, EDITOR -IN EXILE- VoL . ~ - No. 9 MAY 1968 Afro-Americans & Slick John Kennedy Government of the United States is no government T~E of the Afro-Americans at all. The slick John Ken- nedy gang is operating one of the greatest sham govern- ment in the entire world. Afro-Americans and fair minded Od > ~- O THE wN«< /l~USL . lF Yov~Re EyER IN NE60, CALL ME AT whites must be gullible indeed to believe that the racist, KKK dominated so-called U.S. Government is concerned with the welfare and human rights of colored people. The colored people of the USA must bring themselves to realize that taken integration is a slick manuever to check the restlessness of an oppressed people fast becoming infect ed with the germ of total resistance policy developing among all of the oppressed peoples of the world. Token integration means nothing to the masses. Even an idiot should be able to see that so-called Token integration is no more than window dressing designed to lull the poor downtrodden Afro-American to sleep and to make the out side world think that the racist, savage USA is a fountainhead of social justice and democracy. The Afro-American in the USA is facing his greatest crisis since chattel slavery. All forms of violence and underhanded methods o.f extermination are being stepped up against our people. Contrary to what the "big daddies" and their "good nigras" would have us believe about all of the phoney progress they claim the race is making, the True status of the Afro-Ameri- can is s#eadily on the down turn. -

Messmer High School from 1926-2001 Rebecca A

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Dissertations (2009 -) Dissertations, Theses, and Professional Projects Doctrina, Fides, Gubernatio: Messmer High School from 1926-2001 Rebecca A. Lorentz Marquette University Recommended Citation Lorentz, Rebecca A., "Doctrina, Fides, Gubernatio: Messmer High School from 1926-2001" (2010). Dissertations (2009 -). Paper 75. http://epublications.marquette.edu/dissertations_mu/75 DOCTRINA, FIDES, GUBERNATIO: MESSMER HIGH SCHOOL FROM 1926-2001 by Rebecca A. Lorentz, B.A., M.A. A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School, Marquette University, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Milwaukee, Wisconsin December, 2010 i ABSTRACT DOCTRINA, FIDES, GUBERNATIO: MESSMER HIGH SCHOOL FROM 1926-2001 Rebecca A. Lorentz, BA, MA Marquette University, 2010 In 1926, the Archdiocese of Milwaukee opened its first Diocesan high school, hoping thereby to provide Milwaukee‟s north side with its own Catholic school. By 1984 the Archdiocese claimed that the combination of declining enrollment and rising operating costs left it no option other than permanently closing Messmer. In response, a small group of parents and community members aided by private philanthropy managed to reopen the school shortly thereafter as an independent Catholic school. This reemergence suggested a compelling portrait of the meaning given to a school, even as ethnic, religious, and racial boundaries shifted. Modern studies tend to regard Catholic schools as academically outstanding -

Dismantling Respectability: the Rise of New Womanist Communication

Journal of Communication ISSN 0021-9916 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Dismantling Respectability: The Rise of New Womanist Communication Models in the Era Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/joc/advance-article-abstract/doi/10.1093/joc/jqz005/5370149 by guest on 07 March 2019 of Black Lives Matter Allissa V. Richardson Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA 90089, USA Legacy media coverage of the Civil Rights Movement often highlighted charismatic male leaders, such as Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., while scores of Black women worked qui- etly in the background. Today’s leaders of the modern Black Lives Matter movement have turned this paradigm on its face. This case study explores the revamped communi- cation styles of four Black feminist organizers who led the early Black Lives Matter Movement of 2014: Brittany Ferrell, Alicia Garza, Brittany Packnett, and Marissa Johnson. Additionally, the study includes Ieshia Evans: a high-profile, independent, anti–police brutality activist. In a series of semi-structured interviews, the women shared that their keen textual and visual dismantling of Black respectability politics led to a mediated hyper-visibility that their forebearers never experienced. The women share the advantages and disadvantages of this approach, and weigh in on the sustain- ability of their communication methods for future Black social movements. Keywords: Black Feminism, Political Communication, Twitter, Respectability Politics, Social Movements. doi:10.1093/joc/jqz005 Brittany Ferrell remembered the tear gas most. As a frontline demonstrator during what came to be known as the Ferguson protests in August 2014, she recalled the unimaginable sting in her lungs and nose as she gasped for air. -

New LAPD Chief Shares His Policing Vision with South L.A. Black Leaders

Abess Makki Aims to Mitigate The Overcomer – Dr. Bill Water Crises First in Detroit, Then Releford Conquers Major Setback Around the World to Achieve Professional Success (See page A-3) (See page C-1) VOL. LXXVV, NO. 49 • $1.00 + CA. Sales Tax THURSDAY, DECEMBERSEPTEMBER 12 17,- 18, 2015 2013 VOL. LXXXV NO 25 $1.00 +CA. Sales Tax“For Over “For Eighty Over EightyYears TheYears Voice The ofVoice Our of Community Our Community Speaking Speaking for Itselffor Itself” THURSDAY, JUNE 21, 2018 The event was a 'thank you card' to the Los Angeles community for a rich history of support and growth together. The organization will continue to celebrate its 50th milestone throughout the year. SPECIAL TO THE SENTINEL Proclamations and reso- lutions were awarded to the The Brotherhood Cru- organization, including a sade, is a community orga- U.S. Congressional Records nization founded in 1968 Resolution from the 115th by civil rights activist Wal- Congress (House of Repre- ter Bremond. For 35 years, sentatives) Second Session businessman, publisher and by Congresswoman Karen civil rights activist Danny J. Bass, 37th Congressional Bakewell, Sr. led the Institu- District of California. tion and last week, Brother- Distinguished guests hood Crusade president and who attended the event in- CEO Charisse Bremond cluded: Weaver hosted a 50th Anni- CA State Senator Holly versary Community Thank Mitchell; You Event on Friday, June CA State Senator Steve 15, 2018 at the California CA State Assemblymember Science Center in Exposi- Reggie Jones-Sawyer; tion Park. civil rights advocate and The event was designed activist Danny J. -

Persecution and Perseverance: Black-White Interracial Relationships in Piedmont, North Carolina

PERSECUTION AND PERSEVERANCE: BLACK-WHITE INTERRACIAL RELATIONSHIPS IN PIEDMONT, NORTH CAROLINA by Casey Moore A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of North Carolina at Charlotte in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Charlotte 2017 Approved by: ______________________________ Dr. Aaron Shapiro ______________________________ Dr. David Goldfield ______________________________ Dr. Cheryl Hicks ii ©2017 Casey Moore ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii ABSRACT CASEY MOORE. Persecution and perseverance: Black-White interracial relationships in Piedmont, North Carolina. (Under the direction of DR. AARON SHAPIRO) Although black-white interracial marriage has been legal across the United States since 1967, its rate of growth has historically been slow, accounting for less than eight percent of all interracial marriages in the country by 2010. This slow rate of growth lies in contrast to a large amount of national poll data depicting the liberalization of racial attitudes over the course of the twentieth-century. While black-white interracial marriage has been legal for almost fifty years, whites continue to choose their own race or other races and ethnicities, over black Americans. In the North Carolina Piedmont, this phenomenon can be traced to a lingering belief in the taboo against interracial sex politically propagated in the 1890s. This thesis argues that the taboo surrounding interracial sex between black men and white women was originally a political ploy used after Reconstruction to unite white male voters. In the 1890s, Democrats used the threat of interracial sex to vilify black males as sexual deviants who desired equality and voting rights only to become closer to white females. -

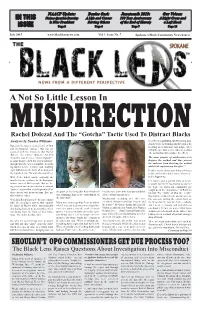

Rachel Dolezal and the “Gotcha” Tactic Used to Distract Blacks Analysis by Sandra Williams Be Defined As Pointing out the Wrong Way

NAACP Update: Denise Osei: Juneteenth 2015: Our Voices: IN THIS Naima Quarles-Burnley A Life and Career 150 Year Anniversary A Right Cross and is New President Serving Others of the End of Slavery a Left Hook ISSUE Page 5 Page 6 Page 7 Page 13 July 2015 www.blacklensnews.com Vol. 1 Issue No. 7 Spokane’s Black Community News Source A Not So Little Lesson In MISDIRECTIONRachel Dolezal And The “Gotcha” Tactic Used To Distract Blacks Analysis by Sandra Williams be defined as pointing out the wrong way. Another way of defining misdirection is by Based on the unprecedented level of fury focusing on its function. Any magic effect and international “outrage” that was as- (what the spectator sees) requires a method sociated with the discovery that Rachel (the method used to produce the effect). Dolezal, the former Spokane NAACP President, was in fact a “white imposter”, The main purpose of misdirection is to as some people called her, you would have disguise the method and thus prevent thought that she was responsible for pull- the audience from detecting the method ing out her service revolver and emptying whilst still experiencing the effect.” eight bullets into the back of an unarmed, In other words, doing something to distract fleeing black man. No wait, that wasn’t her. people so that they don’t notice what is ac- Well, if she didn’t murder anybody, she tually happening. must be the one to blame for the dispropor- If it wasn’t such a painful thing to watch, tionate rates of Black people that are be- it would have been fascinating to observe ing arrested and incarcerated in a criminal the degree to which our community got “justice” system that actually profits off of caught up in the “importance” of Rachel’s the point of declaring that Rachel Dolezal I had no idea at the time how profound that those arrests and incarcerations. -

Board of School Directors Milwaukee, Wisconsin June 8, 2017

BOARD OF SCHOOL DIRECTORS MILWAUKEE, WISCONSIN JUNE 8, 2017 Special meeting of the Board of School Directors called to order by President Sain at 5:37 PM. Present — Directors Báez, Bonds, Falk, Harris, Miller, Phillips (departed 6:30 PM), Voss, Woodward, and President Sain — 9. Absent and Excused — None. The Board Clerk read the following call of the meeting: June 1, 2017 TO THE MEMBERS OF THE BOARD OF SCHOOL DIRECTORS: At the request of President Mark Sain, a special meeting of the Board of School Directors will be held at 5:30 p.m. on Thursday, June 8, 2017, in the Auditorium of the Central Services Building, 5225 West Vliet Street, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, to consider the following items of business: 1. Report and Analysis from the Public Policy Forum on the Milwaukee Public Schools Proposed FY18 Budget 2. Consideration of and Possible Action on Employment, Compensation, and Performance- evaluation Data Relative to the Terms of an Employment Agreement with the Superintendent of Schools In regard to Item 2, above, the Board may retire to executive session pursuant to Wisconsin Statutes, Section 19.85(1)(c), which allows a governmental body to retire to executive session for the purpose of considering employment, promotion, compensation or performance evaluation data of any public employee over which the governmental body has jurisdiction or exercises responsibility. The Board may reconvene in open session to take action on matters discussed in closed session and/or to continue with the remainder of its agenda; otherwise, the Board will adjourn from executive session. JACQUELINE M. MANN, Ph.D. -

With Determination and Fortitude We Come to Vote: Black Organization and Resistance to Voter Suppression in Mississippi

WITH DETERMINATION AND FORTITUDE 195 With Determination and Fortitude We Come to Vote: Black Organization and Resistance to Voter Suppression in Mississippi by Michael Vinson Williams On July 2, 1946, brothers Medgar and Charles Evers, along with four friends, decided they would vote in their hometown of Decatur, Missis- sippi. Both brothers had registered without incident but when the men returned to cast their ballots they were met by a mob of armed whites. The confrontation grew in intensity with each step toward the polling place. After a few nerve-racking moments of yelling and shoving, the Evers group retreated, but the harassment did not end. Medgar Evers recalled that while they were walking away some of the whites followed them and that one man in a 1941 Ford “leaned out with a shotgun, keep- ing a bead on us all the time and we just had to walk slowly and wait for him to kill us …. They didn’t kill us but they didn’t end it, either.” The African American men went home, retrieved guns of their own, and returned to the polling station but decided to leave the weapons in the car. The white mob again prevented them from entering the voting precinct, and the would-be voters gave up.1 1 This article makes use of the many newspaper clippings catalogued in the Allen Eugene Cox Papers housed at the Mitchell Memorial Library Special Collections Department at Mississippi State University (Starkville) and the Trumpauer (Joan Harris) Civil Rights Scrapbooks Collection at the Mississippi Department of Archives and History in Jackson, Mississippi.