Updated Memo Regarding Resolute Forest Products

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Resolute Forest Products Annual Report 2021

Resolute Forest Products Annual Report 2021 Form 10-K (NYSE:RFP) Published: March 1st, 2021 PDF generated by stocklight.com Table of Contents UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K (Mark One) ☒ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 FOR THE FISCAL YEAR ENDED DECEMBER 31, 2020 ☐ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 FOR THE TRANSITION PERIOD FROM TO COMMISSION FILE NUMBER: 001-33776 RESOLUTE FOREST PRODUCTS INC. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 98-0526415 (State or other jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) (I.R.S. employer identification number) 111 Robert-Bourassa Boulevard Suite 5000 Montreal Quebec Canada H3C 2M1 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) (514) 875-2160 (Registrant’s telephone number, including area code) Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: New York Stock Exchange Common Stock, par value $0.001 per share RFP Toronto Stock Exchange (Title of class) (Trading Symbol) (Name of exchange on which registered) Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes ☐ No ☒ Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. Yes ☐ No ☒ Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. -

Building the Resolute of the Future

BUILDING THERESOLUTE resolutefpcom OFTHEFUTURE AnnualReport SHAREHOLDERINFORMATION ANNUALGENERALMEETING INVESTORRELATIONS FORMK Ourannualmeetingofstockholders AlainBourdages ResoluteForestProductsIncfi lesits willbeheldonWednesdayJune VicePresident annualreportonFormKwiththeUS atamEastern atCentredesarts SecuritiesandExchangeCommission deBaieComeaudeBretagne ir resolutefpcom acopyofwhichisincludedwiththis BaieComeauQuebecG C S annualreporttostockholders Canada MEDIA Freecopieswithoutexhibits are availableuponrequesttoResolute’s TRANSFERAGENT SethKursman InvestorRelationsdepartment FORCOMMONSTOCK VicePresident Thecompany’sSECfi lingsannualreports CorporateCommunications ResoluteForestProductsisaglobal Acommitmenttosustainabilityisatthe ComputershareTrustCompanyNA tostockholdersnewsreleasesandother SustainabilityandGovernmentAff airs BUILDING leaderintheforestproductsindustry heartofourcompanycultureItguides POBox CollegeStation investorinformationcanbeaccessedat withadiverserangeofproducts ourapproachtothewaywedobusiness Texas UnitedStates resolutefpcom/investors sethkursman resolutefpcom THERESOLUTE includingmarketpulpwoodproducts everydayWetakeenormouspride tollfreewithin tissuenewsprintandspecialtypapers inthesupportwehavereceivedfrom theUnitedStatesandCanada STOCKLISTINGS OFTHEFUTURE Thecompanyownsoroperates communityandFirstNationsleaders INVESTORINFORMATION overpulppaperwoodproducts customersunionrepresentatives Thesharesofcommonstockof computersharecom/investor ANDFINANCIALREPORTING andtissuefacilitiesintheUnited governmentoffi -

Forest Products Forest Annual Market Annual Review 2014-2015

UNECE Forest Products Forest Annual MarketAnnual Review 2014-2015 UNECE Forest Products - Annual Market Review 2014-2015 UNITED NATIONS UNECE Forest Products Annual Market Review 2014-2015 II UNECE/FAO Forest Products Annual Market Review, 2014-2015 NOTE The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Data for the Commonwealth of Independent States is composed of these twelve countries: Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Republic of Moldova, Russian Federation, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Ukraine and Uzbekistan. DISCLAIMER The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or carry the endorsement of the United Nations. ABSTRACT The Forest Products Annual Market Review 2014-2015 provides a comprehensive analysis of markets in the UNECE region and reports on the main market influences outside the UNECE region, using the best-available data from diverse sources. It covers the range of products from the forest to the end-user: from roundwood and primary-processed products to value-added products and those used in housing. Statistics-based chapters analyse the markets for wood raw materials, sawn softwood, sawn hardwood, wood- based panels, paper, paperboard and woodpulp. Other chapters analyse policies, institutional forestland ownership and its effects on forest products markets, and markets for wood energy. The Review highlights the role of sustainable forest products in international markets. -

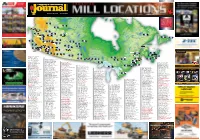

Mill Location Map Is Complete and Up-To-Date

www.forestnet.com — 604.990.9970 Every effort has been made to ensure that the information on this mill location map is complete and up-to-date. Possible errors and omissions are inevitable and we ask that these be brought to Logging & Sawmilling Journals attention. Please Fort Nelson contact [email protected] with updated information. Map Source file National Atlas of Canada. Fort Smith “Source: © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada. Natural Resources Canada. High Level Prince Rupert G LSJ PUBLISHING Terrace Fort St. John Smithers Peace River Goose Bay Fort McMurray Grande Prairie Prince George Gander St. John’s Quesnel Slave Lake Port Hardy Hinton Thompson Williams Lake La Ronge Edmonton Flin Flon Campbell River Loydminster The Pas Kamloops Prince Albert Revelstoke Nanaimo Vancouver Kelowna Calgary Saskatoon ® ® NEED A LIFT? Charlottetown Cranbrook Dolbeau-Mistanssini Lethbridge Medicine Hat Dauphin Regina Moncton British Columbia Board Mills Truro Atco Wood Products Ltd. • Fruitvale • 250-367-9441 Kapuskasing BC Veneer Products Ltd. • Surrey • 604-572-8968 Halifax CIPA Lumber Co. Ltd. • Delta • 604-523-2250 Brandon Kenora Quebec St. John Coastland Wood Industries Ltd. • Nanaimo • 250-754-1962 Canwest Trading Ltd. (Suncoast Lumber & Milling) • Sechelt • 604-885-7313 Dryden Val d´Or Winnipeg Eldcan Forest Products Ltd. • Kamloops • 250-573-1900 Capital Woodwork • Langley • 604-607-5697 Timmins Gorman Bros. Lumber Ltd. • Canoe • 250-833-1260 Carrier Lumber Ltd. • Prince George • 250-563-9271 Louisiana-Pacific Canada Ltd. • Dawson Creek • 250-782-1616 Chimney Creek Lumber Co. Ltd. • Williams Lake • 250-392-7267 Trois-Riviéres Louisiana-Pacific Canada Ltd. • Golden • 250-344-8846 Conifex (Fort St. -

We Are Resolute

WE ARE RESOLUTE 2010SUSTAINABILITy reporT TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 RENEWED 1.1 COMPANY PROFILE 5 1.2 REPORT HIGHLIGHTS 6 1.3 LETTER FROM THE CEO 9 1.4 ABOUT THIS REPORT 11 1.5 SUSTAINABILITY STRATEGY AND KEY COMMITMENTS 15 2 RESPONSIBLE 2.1 FIBER AND FORESTRY 18 2.2 CLIMATE AND ENERGY 26 2.3 MILL ENVIRONMENTAL PERFORMANCE 34 2.4 PRODUCTS 44 2.5 STAKEHOLDER ENGAGEMENT 50 2.6 GOVERNANCE AND CORPORATE CULTURE 56 2.7.1 EMPLOYEES / HUMAN RESOURCES 61 2.7.2 EMPLOYEES / HEALTH AND SAFETY 64 2.8 COMMUNITY 70 2.9 ECONOMIC IMPACTS 76 3 RESOLUTE 3.1 MILL ENVIRONMENTAL PERFORMANCEA DAT 80 3.2 Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) INDEX 88 3.3 GLOSSARY 93 2 FOREST REGENERATION The regeneration of harvested areas is an essential component of sustainable forest management. As a responsible forest manager, Resolute seeks to respect the natural growth cycle of trees, while ensuring biodiversity. In Canada, fiber used in our products is sourced primarily from public land, located mainly in the boreal forest. By law, these woodlands must be promptly regenerated. The boreal forest has a remarkable ability to regenerate on its own. In fact, approximately 75% of the area harvested grows back naturally. Our foresters ensure that the rest is promptly reforested. We planted a total of 62.7 million seedlings in 2010. To put the impact of the forest products industry in per- disturbed annually by wildfires, insects and disease. The spective, it should be noted that approximately 0.2% of series of time-stamped images that follow are represen- the boreal forest is harvested by the industry each year.1 tative of the typical regeneration of a black spruce forest By comparison, five times this amount on average is found in the northern Lac-Saint-Jean, Québec, region. -

2011 Annual Report

RESOLUTE FO r EST P r ODUCTS 2011 ANNUAL REPORT2011 2011 ANNUAL REPORT Printed in Canada resolutefp.com RESOLUTE_RAP_COVER_ANG_R1.indd 1 05/04/12 12:16 FINANCIAL BOard of DIRECTORS HIGHLIGHTS Richard B. EVANS JEFFREy A. HEARN 2, 4 Michael S. ROUSSEAU 1, 3 1 Audit Committee Non-Executive Chairman, Corporate Director Executive Vice President 2 Environmental, Health 0 1 and Safety Committee AbitibiBowater Inc. 1, 3 and Chief Financial Officer, Alain RHÉAUME 3 LETter tO Air Canada Finance Committee Richard GARNEAU Managing Partner, 4 Human Resources and SHAREHOLDERS 2, 4, President and Trio Capital Inc. DAvid H. Wilkins Compensation/Nominating and Governance Committee Chief Executive Officer, 3, 4, 5 Partner, Nelson Mullins Riley & AbitibiBowater Inc. PAul C. RIVETT Scarborough LLP; Former U.S. 5 Not standing for re-election at Vice President and Ambassador to Canada the May 23, 2012, annual meeting 02 1, 2, 3 Richard D. FALCONER Chief Legal Officer, Fairfax of stockholders EXECUTIVE Corporate Director Financial Holdings Limited 04 TEAM EXECUTIVE OFFICERS RESOLUTE AT A GLANCE Richard GARNEAU Pierre LABERGE YVEs LAFLAMME JACQUEs P. VACHON President and Senior Vice President, Senior Vice President, Wood Senior Vice President, Chief Executive Officer Human Resources Products, Procurement and Corporate Affairs and 05 Information Technology Chief Legal Officer Alain Boivin John LAFAVE PRODUCT Senior Vice President, Senior Vice President, Jo-Ann LONgwORTH OVERVIEW Pulp and Paper Operations Pulp and Paper Sales Senior Vice President and 06 and Marketing Chief Financial Officer NEW IDENTITY Shareholder INFORMATION ANNUal General MEETING MEDIA 08 Seth KURSMAN Our annual meeting of stockholders will be held Vision and on Wednesday, May 23, 2012, at 8:00 AM (Eastern), Vice President, Corporate Communications, VALUES at the Hilton Charlotte Center City, North Carolina Room, Sustainability and Government Relations 3rd Floor, 222 East Third Street, Charlotte, North Carolina. -

2017 Annual and Sustainability Report

2017 ANNUAL AND SUSTAINABILITY REPORT resolutefp.com 1 RESOLUTE FOREST PRODUCTS — 2017 ANNUAL AND SUSTAINABILITY REPORT A REWARDING CULTURE Over the past six years, Resolute In recognition of our industry-leading Forest Products has emerged as a sustainability, environmental and safety performance, Resolute won over 20 regional, global sustainability leader, working North American and international awards and closely with employees, retirees, union distinctions in the past year alone. representatives, customers, business We value this recognition because it provides and Aboriginal partners, community tangible proof that our vision and values are not leaders, government officials, and merely aspirational words; they are the driving force behind our improved performance and industry peers on issues that matter to global success. The awards garnered in 2017 us all: protecting the natural resources speak directly to our core values of working safely, in our care, mitigating climate change, being accountable, ensuring sustainability and investing in clean sources of energy succeeding together. Our achievements in sustainable development as well as our and deepening our commitment to business practices reflect the principled Aboriginal peoples. Our vision and leadership of our management team values capture our business approach and the hard work and dedication and our shared sense of purpose, of our employees. guiding our business decisions, actions and behaviors. Our success is linked to a rewarding culture, where profitability and sustainability -

10-Q Quarterly Financial Report

Table of Contents UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-Q (Mark One) QUARTERLY REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE ☒ SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 FOR THE QUARTERLY PERIOD ENDED SEPTEMBER 30, 2020 TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE ☐ SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 FOR THE TRANSITION PERIOD FROM TO COMMISSION FILE NUMBER: 001-33776 RESOLUTE FOREST PRODUCTS INC. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 98-0526415 (State or other jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) (I.R.S. employer identification number) 111 Robert-Bourassa Boulevard Suite 5000 Montreal Quebec Canada H3C 2M1 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) (514) 875-2160 (Registrant’s telephone number, including area code) (Former name, former address and former fiscal year, if changed since last report) Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: New York Stock Exchange Common Stock, par value $0.001 per share RFP Toronto Stock Exchange (Title of class) (Trading Symbol) (Name of exchange on which registered) Indicate by check mark whether the registrant: (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. Yes ☒ No ☐ Indicate by check mark whether the registrant has submitted electronically every Interactive Data File required to be submitted pursuant to Rule 405 of Regulation S-T (§232.405 of this chapter) during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to submit such files). -

MANAGEMENT PROXY STATEMENT ANNUAL MEETING of STOCKHOLDERS MAY 21, 2021 Resolute Forest Products Inc

MANAGEMENT PROXY STATEMENT ANNUAL MEETING OF STOCKHOLDERS MAY 21, 2021 Resolute Forest Products Inc. 111 Robert-Bourassa Boulevard, Suite 5000 Montreal, Quebec H3C 2M1 Canada April 9, 2021 Dear Stockholder: We cordially invite you to attend the annual meeting of stockholders of Resolute Forest Products Inc. to be held online through a virtual web conference at https://web.lumiagm.com/295854943 on Friday, May 21, 2021, at 9:00 a.m. (Eastern). The annual meeting is being held entirely online due to the public health impact of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) and to allow us to continue to proceed with the meeting while mitigating health and safety risks to participants. You will be able to attend and participate in the annual meeting online at https://web.lumiagm.com/295854943 where you will be able to listen to the meeting live, submit questions and vote your shares. The notice of internet availability of proxy materials provides you with information on how to access the proxy materials and obtain the details of the business to be conducted at the meeting. In addition to the formal items of business to be brought before the meeting, we will report on our business and respond to stockholder questions. Whether or not you plan to attend online, you can ensure that your shares are represented at the meeting by promptly voting and submitting your proxy or voting instruction card by internet or, if you have requested to receive a paper copy of the proxy materials, by completing, signing, dating and returning your proxy form in the enclosed envelope. -

Resolute Highlights Table 1 About Us of Contents 1 Strategy 2 Operations

RESOLUTE HIGHLIGHTS TABLE 1 ABOUT US OF CONTENTS 1 STRATEGY 2 OPERATIONS 4 BUSINESS SEGMENTS 4 WOOD 5 PULP 6 TISSUE 7 PAPER 8 SUSTAINABILITY 9 ECONOMIC INDICATORS 11 ENVIRONMENTAL INDICATORS 14 SOCIAL INDICATORS 1 RESOLUTE FOREST PRODUCTS — HIGHLIGHTS ABOUT US Resolute Forest Products is a global leader in the forest products industry with a diverse range of products, including market pulp, tissue, wood products, newsprint and specialty papers, which are marketed in close to 70 countries. The company owns or operates some 40 facilities, as well as power generation assets, in the United States and Canada. Resolute has third-party certified 100% of its managed woodlands to internationally recognized sustainable forest management standards. STRATEGY At Resolute, our business and sustainability strategies have been expressly developed to align our efforts in environmental stewardship and social responsibility with our business objectives. This approach reinforces our vision that profitability and sustainability drive our future. Business Strategy Our corporate strategy is focused on continuing to transform the company away from mature markets and declining products toward a more profitable and sustainable organization over the long run, founded on a competitive portfolio of manufacturing assets and a solid presence in long-term growth markets. Our strategy is based on: • maximizing value generation from paper • growing in pulp and wood products • integrating our pulp into value-added, quality tissue • investing in product innovation • maintaining -

Finance and Managerial Control in the US Forest Products Industry, 1945-2008

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 5-2012 Seeing the Forest for the Trees: Finance and Managerial Control in the US Forest Products Industry, 1945-2008 Andrew Augustus Gunnoe [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Political Economy Commons Recommended Citation Gunnoe, Andrew Augustus, "Seeing the Forest for the Trees: Finance and Managerial Control in the US Forest Products Industry, 1945-2008. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2012. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/1299 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Andrew Augustus Gunnoe entitled "Seeing the Forest for the Trees: Finance and Managerial Control in the US Forest Products Industry, 1945-2008." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Sociology. Paul K. Gellert, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Jon Shefner, Sherry Cable, Donald D. Hodges -

RESOLUTE FOREST PRODUCTS INC. (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

Table of Contents UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K (Mark One) ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 FOR THE FISCAL YEAR ENDED DECEMBER 31, 2012 ¨ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 FOR THE TRANSITION PERIOD FROM TO COMMISSION FILE NUMBER: 001-33776 RESOLUTE FOREST PRODUCTS INC. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 98-0526415 (State or other jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) (I.R.S. employer identification number) 111 Duke Street, Suite 5000; Montreal, Quebec; Canada H3C 2M1 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) (514) 875-2515 (Registrant’s telephone number, including area code) Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: New York Stock Exchange Common Stock, par value $.001 per share Toronto Stock Exchange (Title of class) (Name of exchange on which registered) Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes No ¨ Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. Yes ¨ No Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days.