Faber Firsts Lord of the Flies by William Golding

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Symbolism of Power in William Golding's Lord of the Flies

Estetisk-filosofiska fakulteten Engelska Björn Bruns The Symbolism of Power in William Golding’s Lord of the Flies Engelska C-uppsats Datum: Hösttermin 2008/2009 Handledare: Åke Bergvall Examinator: Mark Troy Karlstads universitet 651 88 Karlstad Tfn 054-700 10 00 Fax 054-700 14 60 [email protected] www.kau.se The Symbolism of Power in William Golding’s Lord of the Flies An important theme in William Golding’s novel Lord of the Flies is social power relations. These power relations are everywhere on the island, and are shown at different levels throughout the novel. These power relations are illustrated by symbols in the novel, which center on two different power systems, a democratic system, with Ralph as the head, and a dictatorial system with Jack as the leader. Sometimes these symbols are tied so closely together to both power systems that they mean different things for each of them. The aim of this essay is to investigate the different kinds of symbols that are used in the novel, and to show how they are tied to its social power relations. Those symbols that I have found are always important items that either Ralph or Jack use intentionally or unintentionally. The use of symbols is crucial to this novel, thus Golding shows us that an item is more powerful than it first seems. An important theme in William Golding’s novel Lord of the Flies is social power relations. These power relations are everywhere on the island, and are shown at different levels throughout the novel. The novel, according to Kristin Olsen, concentrates on describing “the desire for power, […] the fear of other people, anger and jealousy” (2). -

LORD of the FLIES by William Golding Adapted by Nigel Williams Directed by Marcus Romer Education Resource Pack Updated Sept 08 Created by Helen Cadbury

LORD OF THE FLIES by William Golding adapted by Nigel Williams directed by Marcus Romer Education Resource Pack updated Sept 08 created by Helen Cadbury ! www.pilot-theatre.com! ! ! ! ! ! 1 CONTENTS Introduction 3 Synopsis 4 ce Pack About Pilot 5 Director's Vision 6 William Golding 7 Nigel Williams 8 From Page to Stage 9 The Casting Process The Casting Breakdown 10 From Page to Stage 11 A Day in Rehearsal 12 Meet the Actor - Davood Ghadami 13 Meet the Actor - Dominic Doughty 14 d of the Flies Education Resour The Cast 15 Lor Behind the Scenes at Pilot Theatre 16 with Katie Fathers - Projects Co-ordinator WORKSHOPS AND CLASSROOM 17 ACTIVITIES Working from Themes The Island - Descriptive Language 18 - continued 19 Betrayal - Piggy and Ralph 20 Betrayal/ first script extract 21 Betrayal/ second script extract 22 Betrayal/ third script extract 23 Killing The Pig - Dramatic Tension 24 Killing the Pig/script extract 25 Killing the Pig/novel extract 26 Further Resources 27 ! www.pilot-theatre.com! ! ! ! ! ! 2 INTRODUCTION Welcome to Pilot Theatre’s 10th Anniversary Production of Lord of The Flies ce Pack Lord of the Flies is a timeless piece of work following the central theme of the journey from boyhood to manhood. William Golding described writing his novel as ‘like lamenting the lost childhood of the world’. Our production remains true to the vision of the novel, but in keeping with Pilot’s style of performance, this show is dangerous, contemporary and exciting. This education pack offers resources that give an insight into the production and that explore the themes of the play. -

Teacher and Student Resource Pack Lord of the Flies Teacher and Student Resource Pack 1 1

A NEW ADVENTURES AND RE:BOURNE PRODUCTION TEACHER AND STUDENT RESOURCE PACK LORD OF THE FLIES TEACHER AND STUDENT RESOURCE PACK 1 1. USING THIS RESOURCE PACK p3 2. WILLIAM GOLDING’S NOVEL p4 William Golding and Lord of the Flies Novel’s Plot Characters Themes and Symbols 3. NEW ADVENTURES AND RE:BOURNE’S LORD OF THE FLIES p11 An Introduction By Matthew Bourne Production Research Some Initial Ideas Plot Sections Similarities and Differences 4. PRODUCTION ELEMENTS p21 Set and Costume Costume Supervisor Music Lighting 5. PRACTICAL WORKSHEETS p26 General Notes Character Devising and Developing Movement 6. REFLECTING AND REVIEWING p32 Reviewing live performance Reviews and Editorials for New Adventures and Re:Bourne’s Production of Lord of the Flies 7. FURTHER WORK p32 Did You Know? It’s An Adventure Further Reading Essay Questions References Contributors LORD OF THE FLIES TEACHER AND STUDENT RESOURCE PACK 2 1. USING THIS RESOURCE PACK This pack aims to give teachers and students further understanding of New Adventures and Re:Bourne’s production of Lord of the Flies. It contains information and materials about the production that can be used as a stimulus for written work, discussion and practical activities. There are worksheets containing information and resources that can be used to help build your own lesson plans and schemes of work based on Lord of the Flies. This pack contains subject material for Dance, Drama, English, Design and Music. Discussion and/or Evaluation Ideas Research and/or Further Reading Activities Practical Tasks Written Work The symbols above are to guide you throughout this pack easily and will enable you to use this guide as a quick reference when required. -

Bloom's Modern Critical Interpretations: Lord of the Flies

Bloom's Modern Critical Interpretations The Adventures of The Grapes of Wrath Portnoy’s Complaint Huckleberry Finn Great Expectations A Portrait of the Alice’s Adventures in The Great Gatsby Artist as a Young Wonderland Hamlet Man All Quiet on the The Handmaid’s Tale Pride and Prejudice Western Front Heart of Darkness Ragtime As You Like It I Know Why the The Red Badge of The Ballad of the Sad Caged Bird Sings Courage Café The Iliad The Rime of the Beloved Jane Eyre Ancient Mariner Beowulf The Joy Luck Club The Rubáiyát of Billy Budd, Benito The Jungle Omar Khayyám Cereno, Bartleby the Long Day’s Journey The Scarlet Letter Scrivener, and Other Into Night A Separate Peace Tales Lord of the Flies Silas Marner Black Boy The Lord of the Rings Song of Solomon The Bluest Eye Love in the Time of The Stranger Cat on a Hot Tin Cholera A Streetcar Named Roof Macbeth Desire The Catcher in the The Man Without Sula Rye Qualities The Sun Also Rises Catch-22 The Metamorphosis The Tale of Genji The Color Purple Miss Lonelyhearts A Tale of Two Cities Crime and Moby-Dick The Tempest Punishment Night Their Eyes Were The Crucible 1984 Watching God Darkness at Noon The Odyssey Things Fall Apart Death of a Salesman Oedipus Rex To Kill a Mockingbird The Death of Artemio The Old Man and the Ulysses Cruz Sea Waiting for Godot The Divine Comedy On the Road The Waste Land Don Quixote One Flew Over the White Noise Dubliners Cuckoo’s Nest Wuthering Heights Emerson’s Essays One Hundred Years of Young Goodman Emma Solitude Brown Fahrenheit 451 The Pardoner’s Tale Frankenstein Persuasion Bloom’s Modern Critical Interpretations William Golding’s Lord of the Flies New Edition Edited and with an introduction by Harold Bloom Sterling Professor of the Humanities Yale University Bloom’s Modern Critical Interpretations: Lord of the Flies—New Edition Copyright © 2008 Infobase Publishing Introduction © 2008 by Harold Bloom All rights reserved. -

William Golding's Novel Conveys More Than One Idea About Individuals And

William Golding’s “Lord of the Flies” for the Common Core Worksheet 6. Theme Ideas in Lord of the Flies (teacher version) William Golding’s novel conveys more than one idea about individuals and groups. Consider information from the text supplied for you; write in the theme idea that you think the author is trying to convey through that scene. Information from the text Theme idea Piggy is overweight and asthmatic; he has weak People often judge by appearances and victimize vision; he is smart and not at all athletic. The others who seem somehow inadequate. The other boys tend to discount his ideas and make strong tend to bully the apparently weak. fun of him. The boys on the island end up at war with each War is an inevitable product of human nature. other, and war in the outside world is what led to When there is no real reason to fight, people their castaway experience in the first place. create one. When Jack first has a chance to kill a pig, he Killing, with practice, becomes easy and even hesitates. When the boys kill the sow, they are pleasurable. People can become inured to what at filled with bloodlust and savagery. first seems awful. As the novel draws to a close, it seems certain Sometimes miraculous saves do occur. (Imagine that Ralph will be killed and his head will be how different the novel would be if it ended with mounted on a stick. At the very last minute, a Ralph’s death and an island covered with burned naval officer arrives to save his life and get the out flora and fauna.) boys off the island. -

William Golding's Apocalyptic Vision in Lord of the Flies and Pincher Martin

Prague Journal of English Studies Volume 6, No. 1, 2017 ISSN: 1804-8722 (print) '2,10.1515/pjes-2017-0003 ISSN: 2336-2685 (online) William Golding’s Apocalyptic Vision in Lord of the Flies and Pincher Martin Arnab Chatterjee Humanity has long been haunted by the notions of Armageddon and the coming of a Golden Age. While the English Romantic poets like Shelley saw hopes of a new millennium in poems like “Queen Mab” and “ e Revolt of Islam”, others like Blake developed their own unique “cosmology” in their longer poems that were nevertheless coloured with their vision of redemption and damnation. Even Hollywood movies, like e Book of Eli (2010), rehearse this theme of salvation in the face of imminent annihilation time and again. Keeping with such trends, this paper would like to trace this line of apocalyptic vision and subsequent hopes of renewal with reference to William Golding’s debut novel Lord of the Flies (1954) and his Pincher Martin (1956). While in the former, a group of young school boys indulge in violence, fi rstly for survival, and then for its own sake, in the latter, a lonely, shipwrecked survivor of a torpedoed destroyer clings to his own hard, rock-like ego that subsequently is a hurdle for his salvation and redemption, as he is motivated by a lust for life that makes him exist in a diff erent moral and physical dimension. In Lord of the Flies, the entire action takes place with nuclear warfare presumably as its backdrop, while Pincher Martin has long been interpreted as an allegory of the Cold War and the resultant fear of annihilation from nuclear fallout (this applies to Golding’s debut novel as well). -

On Symbolic Significance of Characters in Lord of the Flies

English Language Teaching March, 2009 On Symbolic Significance of Characters in Lord of the Flies Xiaofang Li & Weihua Wu School of Foreign Languages Yan’an University Yangjialing 716000, China E-mail: lxf0318 @126.com. Abstract The characters in Lord of the Flies possess recognizable symbolic significance, which make them as the sort of people around us. Ralph stands for civilization and democracy; Piggy represents intellect and rationalism; Jack signifies savagery and dictatorship; Simon is the incarnation of goodness and saintliness. All of these efficiently portray the microcosm of that society. Keywords: William Golding, Characters, Symbolic significance 1. Introduction Lord of the Flies is written by famous contemporary novelists William Golding (1911-1993), who won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1983.Since its publication in 1954, the novel has become the best sellers and has been studied in schools and universities nearly all over the world. Such success has great relationship with the author’s unique writing style—he puts symbolism in a delicate blending of fable, allegory and adventure story. Lord of the Flies depicts the transformation into savagery of a group of English schoolboys stranded on a desert island without adult supervision in the aftermath of a plane crash. At the beginning, the children manage to take care of themselves and expect the hope of rescue. However, the boys are soon controlled by the fear in their hearts. The island community breaks up into two rival groups, represented respectively by Ralph, who insists on civilized values and the hope of rescue; Jack, who wants to enjoy the freedom and benefits of hunting on the island. -

Lord of the Flies About the Author (William Golding) Born in Cornwall

Lord of the Flies About the Author (William Golding) ➢ Born in Cornwall on 19th September 1911. ➢ He attended Marlborough Grammar School, then went to Oxford with the intention of reading science but eventually graduated in English in 1933. ➢ He became a teacher. ➢ In 1939 he married Ann Brookfield and a year later volunteered for the Royal Navy in which he served until 1945. ➢ He had witnessed the two World Wars, the First World War as a child while in WWII, he participated in action. He took part in the D-Day landings in Normandy and rose to the rank of the lieutenant. ➢ After the War ended, he returned back to teaching taking up a job at Bishop Wordsworth’s School, Salisbury and after his superannuation he became a full time author. ➢ Lord of the Flies (1954) in his first published novel and it was made into a film in 1963. ➢ His other notable publications include The Inheritors (1955), Pincher Martin (1956), The Brass Butterfly (1958), Free Fall (1959), The Spire (1964), The Hot Gates (1965), The Pyramid (1967), The Scorpion God (1971), Darkness Visible (1979), Rites of Passage (1980), A Moving Target (1982) and The Paper Man (1984). ➢ He won the James Tait Black Memorial Prize and The Booker McConnell Prize in 1980 and won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1983. ➢ He died on 19th June, 1993 at the age of 81 years. Possible Sources of the novel Although the adventure-island-story tradition can be traced back to a host of novels like R.L. Stevenson’s Treasure Island, Arthur Ransome’s Swallows and Amazons, Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe, yet the most notable influence had been R.M. -

Republic of Turkey Firat University Institute of Social Sciences Department of Western Languages and Literatures Program of English Language and Literature

REPUBLIC OF TURKEY FIRAT UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE OF SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF WESTERN LANGUAGES AND LITERATURES PROGRAM OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE AN ECOCRITICAL READING OF THE INHERITORS BY WILLIAM GOLDING MASTER THESIS SUPERVISOR PREPARED BY Assist. Prof. Dr. Seda ARIKAN Emrah GÜMÜŞBOĞA ELAZIĞ - 2015 II ÖZET Yüksek Lisans Tezi William Golding’in The Inheritors Adlı Romanının Ekoeleştirel Bir İncelemesi Emrah GÜMÜŞBOĞA Fırat Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Batı Dilleri ve Edebiyatları Anabilim Dalı İngiliz Dili ve Edebiyatı Bilim Dalı Elazığ – 2015, Sayfa: V + 86 Bu çalışma William Golding’in The Inheritors adlı eserinde geçen doğa tasavvurunun ekoeleştirel bakış açısıyla tartışılmasını amaçlamaktadır. Giriş ve sonuç bölümleri ve dört ana bölümden oluşan çalışma, ekoeleştirinin ortaya çıkışını ve gelişim sürecini inceleyerek The Inheritors adlı romanda ekoleştirel öğelerin yansımasını ele almaktadır. William Golding’in dünya görüşünü ve insanoğluna bakış açısını yansıtan bu roman, günümüz ekoeleştirel söylemleri önceler niteliktedir. Bu bağlamda, insanoğlunun doğaya karşı yıkıcı eylemleri ve doğayı sömürü üzerine kurulu solipsist yaklaşımının ilksel örnekleri, arkaik bir dünyayı temsil eden bu romanda resmedilmektedir. Bu çalışma Golding’in resmettiği bu dünyayı ekoleştirel bir söylem olarak ortaya koymayı amaçlamaktadır. Anahtar Kelimeler: Ekoeleştiri, William Golding, The Inheritors , Neanderthals, Homo sapiens III ABSTRACT Master Thesis An Ecocritical Reading of The Inheritors by William Golding Emrah GÜMÜŞBOĞA Fırat University Institute of Social Sciences Department of Western Languages and Literatures Program of English Language and Literature Elazığ - 2015, Sayfa: V + 86 This study aims to discuss the concept of nature in William Golding’s novel The Inheritors through ecocritical approach. The study consisting of four main chapters with an introduction and a conclusion examines the rise and development of ecocriticism and addresses reflections of ecocritical elements in The Inheritors. -

William Golding's the Paper Men: a Critical Study درا : روا و ر ل ورق

William Golding’s The Paper Men: A Critical study روا و ر ل ورق : درا Prepared by: Laheeb Zuhair AL Obaidi Supervised by: Dr. Sabbar S. Sultan A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Master of Arts in English Language and Literature Department of English Language and Literature Faculty of Arts and Sciences Middle East University July, 2012 ii iii iv Acknowledgment I wish to thank my parent for their tremendous efforts and support both morally and financially towards the completion of this thesis. I am also grateful to thank my supervisor Dr. Sabbar Sultan for his valuable time to help me. I would like to express my gratitude to the examining committee members and to the panel of experts for their invaluable inputs and encouragement. Thanks are also extended to the faculty members of the Department of English at Middle East University. v Dedication I dedicate this thesis to my precious father; To my beloved mother; To my two little brothers; To my family, friends, and to all people who helped me complete this thesis. vi Table of contents Subject A Thesis Title I B Authorization II C Thesis Committee Decision III D Acknowledgment IV E Dedication V F Table of Contents VI G English Abstract VIII H Arabic Abstract IX Chapter One: Introduction 1.0 Introduction 1 1.1 Golding and Gimmick 2 1.2 Use of Symbols 4 1.3 Golding’s Recurrent Theme (s) 5 1.4 The Relationship between Creative Writer and 7 Biographers or Critics 1.6 Golding’s Biography and Writings 8 1.7 Statement of the problem 11 1.8 Research Questions 11 1.9 Objectives of the study 12 1.10 Significance of the study 12 1.11 Limitations of the study 13 1.12 Research Methodology 14 Chapter Two: Review of Literature 2.0 Literature Review 15 Chapter Three: Discussion 3.0 Preliminary Notes 35 vii 3.1 The Creative Writer: Between Two Pressures 38 3.2 The Nature of Creativity: Seen from the Inside and 49 Outside Chapter Four 4.0 Conclusion 66 References 71 viii William Golding’s The Paper Men: A Critical Study Prepared by: Laheeb Zuhair AL Obaidi Supervised by: Dr. -

William Golding List

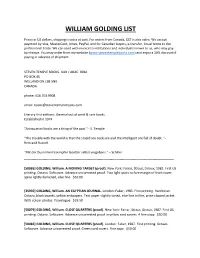

WILLIAM GOLDING LIST Prices in US dollars, shipping is extra at cost. For orders from Canada, GST is also extra. We accept payment by Visa, MasterCard, Amex, PayPal, and for Canadian buyers, e-transfer. Usual terms to the professional trade. We can send with invoice to institutions and individuals known to us, who may pay by cheque. You may order from my website (www.steventemplebooks.com) and enjoy a 10% discount if paying in advance of shipment. STEVEN TEMPLE BOOKS. ILAB / ABAC. IOBA PO BOX 45 WELLAND ON L3B 5N9 CANADA phone: 416.703.9908 email: [email protected] Literary first editions. General out of print & rare books. Established in 1974. "Antiquarian books are a thing of the past." - S. Temple “The trouble with the world is that the stupid are cocksure and the intelligent are full of doubt. “- Bertrand Russell "Mit der Dummheit kaempfen Goetter selbst vergebens." – Schiller ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- [50085] GOLDING, William. A MOVING TARGET (proof). New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 1982. First US printing. Octavo. Softcover. Advance uncorrected proof. Two light spots to fore margin of front cover, spine lightly darkened, else fine. $50.00 [35930] GOLDING, William. AN EGYPTIAN JOURNAL. London: Faber, 1985. First printing. Hardcover. Octavo, black boards, yellow endpapers. Text paper slightly toned, else fine in fine, price-clipped jacket. With colour photos. Travelogue. $19.50 [50079] GOLDING, William. CLOSE QUARTERS (proof). New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 1987. First US printing. Octavo. Softcover. Advance uncorrected proof in yellow card covers. A fine copy. $50.00 [50083] GOLDING, William. CLOSE QUARTERS (proof). London: Faber, 1987. First printing. -

Moral Sub-Structures As the Foundation of William Golding's

www.ijcrt.org © 2021 IJCRT | Volume 9, Issue 2 February 2021 | ISSN: 2320-2882 Moral Sub-structures as the Foundation of William Golding’s Novels LESHVEER SINGH RESEARCH SCHOLAR M.J.P.R.K.U. BAREILLY INDIA ANURADHA SINGH ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR Dept. OF ENGLISH, GOKULDAS H. G. PG COLLEGE MORADABAD INDIA. In Golding’s words we are a species that produces evil as a bee produces honey. Naturally as humble insects produce harmony and sweetness, we produce the wickedness and violence which spoils our lives. The purpose of Golding’s writing is not say-sex or geometry. It is just understanding. The understanding of ‘terrible disease’ and to rouse an alertness amids people and help in making this universe a paradise which man seems to have lost. Each and every novel of Golding searches the predicament of human life which is full of decay and fall due to the original sin committed by our first parents Adam and Eve. He is strongly adhere to the biblical term ‘idolatry’. By this man isolates himself off from the Supreme power whom we called God. My aim is to point out the ‘truths’ and probes the different state of human mind and also religious concerns hidden in the mighty lines of William Golding’s novels. Like the plays of Shakespeare, the novels of Golding serving its purpose of filling the faith into human mind which has gone a long long ago. The novels of Golding, namely, ‘Lord of the Flies’, ‘The Inheritors’, ‘Pincher Martin’ and ‘Free Fall’ are worth mentioning in this connection.