9780521540568.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

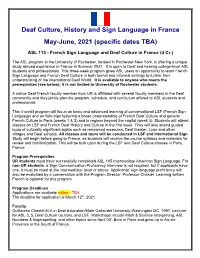

Deaf Culture, History and Sign Language in France May-June, 2021 (Specific Dates TBA)

Deaf Culture, History and Sign Language in France May-June, 2021 (specific dates TBA) ASL 113 - French Sign Language and Deaf Culture in France (4 Cr.) The ASL program at the University of Rochester, located in Rochester New York, is offering a unique study abroad experience in France in Summer 2021. It is open to Deaf and hearing college-level ASL students and professionals. This three-week program gives ASL users an opportunity to learn French Sign Language and French Deaf Culture in both formal and informal settings to further their understanding of the international Deaf World. It is available to anyone who meets the prerequisites (see below); it is not limited to University of Rochester students. A native Deaf French faculty member from UR is affiliated with several faculty members in the Deaf community and they jointly plan the program, schedule, and curriculum offered to ASL students and professionals. This 4-credit program will focus on basic and advanced learning of conversational LSF (French Sign Language) and on field trips fostering a broad understanding of French Deaf Culture and general French Culture in Paris (weeks 1 & 2) and in regions beyond the capital (week 3). Students will attend classes on LSF and French Deaf History and Culture in the first week. They will also attend guided tours of culturally significant sights such as renowned museums, Deaf theater, Lyon and other villages and Deaf schools. All classes and tours will be conducted in LSF and International Sign. Study will begin before going to France, as students will receive the course syllabus and materials for review and familiarization. -

Technical Report, Vol

CRL Technical Report, Vol. 19 No. 1, March 2007 CENTER FOR RESEARCH IN LANGUAGE March 2007 Vol. 19, No. 1 CRL Technical Reports, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla CA 92093-0526 Tel: (858) 534-2536 • E-mail: [email protected] • WWW: http://crl.ucsd.edu/newsletter/current/TechReports/articles.html TECHNICAL REPORT Arab Sign Languages: A Lexical Comparison Kinda Al-Fityani Department of Communication, University of California, San Diego EDITOR’S NOTE The CRL Technical Report replaces the feature article previously published with every issue of the CRL Newsletter. The Newsletter is now limited to announcements and news concerning the CENTER FOR RESEARCH IN LANGUAGE. CRL is a research center at the University of California, San Diego that unites the efforts of fields such as Cognitive Science, Linguistics, Psychology, Computer Science, Sociology, and Philosophy, all who share an interest in language. The Newsletter can be found at http://crl.ucsd.edu/newsletter/current/TechReports/articles.html. The Technical Reports are also produced and published by CRL and feature papers related to language and cognition (distributed via the World Wide Web). We welcome response from friends and colleagues at UCSD as well as other institutions. Please visit our web site at http://crl.ucsd.edu. SUBSCRIPTION INFORMATION If you know of others who would be interested in receiving the Newsletter and the Technical Reports, you may add them to our email subscription list by sending an email to [email protected] with the line "subscribe newsletter <email-address>" in the body of the message (e.g., subscribe newsletter [email protected]). -

Sign Language Typology Series

SIGN LANGUAGE TYPOLOGY SERIES The Sign Language Typology Series is dedicated to the comparative study of sign languages around the world. Individual or collective works that systematically explore typological variation across sign languages are the focus of this series, with particular emphasis on undocumented, underdescribed and endangered sign languages. The scope of the series primarily includes cross-linguistic studies of grammatical domains across a larger or smaller sample of sign languages, but also encompasses the study of individual sign languages from a typological perspective and comparison between signed and spoken languages in terms of language modality, as well as theoretical and methodological contributions to sign language typology. Interrogative and Negative Constructions in Sign Languages Edited by Ulrike Zeshan Sign Language Typology Series No. 1 / Interrogative and negative constructions in sign languages / Ulrike Zeshan (ed.) / Nijmegen: Ishara Press 2006. ISBN-10: 90-8656-001-6 ISBN-13: 978-90-8656-001-1 © Ishara Press Stichting DEF Wundtlaan 1 6525XD Nijmegen The Netherlands Fax: +31-24-3521213 email: [email protected] http://ishara.def-intl.org Cover design: Sibaji Panda Printed in the Netherlands First published 2006 Catalogue copy of this book available at Depot van Nederlandse Publicaties, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, Den Haag (www.kb.nl/depot) To the deaf pioneers in developing countries who have inspired all my work Contents Preface........................................................................................................10 -

Florida Department of Education Home Language Codes

Florida Department of Education Home Language Codes Code Home Language OM (Afan) Oromo AB Abkhazian AC Abnaki AD Achumawi AA Afar AK Afrikaans AE Ahtena EF Akan EK Akateko AF Alabama AL Albanian, Shqip AG Aleut AH Algonquian WJ American Sign Language AM Amharic AI Apache AR Arabic AJ Arapaho AO Araucanian AP Arikara AN Armenian, Hayeren AS Assamese AQ Athapascan AT Atsina AU Atsugewi AV Aucanian WK Awadhi AW Aymara AZ Azerbaijani AX Aztec BA Bantu BC Bashkir BQ Basque, Euskera BS Bassa BJ Belarusian Code Home Language BE Bengali, Bangla BR Berber BP Bhojpuri DZ Bhutani BH Bihari BI Bislama BG Blackfoot BF Breton BL Bulgarian BU Burmese, Myanmasa BD Byelorussian CB Caddo CC Cahuilla CD Cakchiquel CA Cambodian, Khmer CN Cantonese EC Carolinian CT Catalan CE Cayuga ZA Cebuano ED Chamorro CF Chasta Costa CG Chemeheuvi CI Cherokee CJ Chetemacha CK Cheyenne ZB Chhattisgarhi ZC Chinese, Hakka ZD Chinese, Min Nau (Fukienese or Fujianese) CH Chinese, Zhongwen CL Chinook Jargon CM Chiricahua ZE Chittagonian CP Chiwere CQ Choctaw CS Chumash EE Chuukese/Trukese Code Home Language CU Clallam CV Coast Miwok CW Cocomaricopa CX Coeur D’Alene CY Columbia DF Comanche CO Corsican DG Cowlitz DJ Cree ZF Creole HR Croatian, Hrvatski DK Crow DH Cuna DI Cupeno CZ Czech DB Dakota DA Danish DL Deccan DC Delaware DD Delta River Yuman DE Diegueno DU Dutch, Netherlands DO Dzongkha EN English EA Eskimo EO Esperanto ES Estonian EB Eyak FO Faroese FA Farsi, Persian FJ Fijian FL Filipino FI Finnish, Suomi FB Foothill North Yokuts FC Fox FR French FD French Cree Code Home -

An Animated Avatar to Interpret Signwriting Transcription

An Animated Avatar to Interpret SignWriting Transcription Yosra Bouzid Mohamed Jemni Research Laboratory of Technologies of Information and Research Laboratory of Technologies of Information and Communication & Electrical Engineering (LaTICE) Communication & Electrical Engineering (LaTICE) ESSTT, University of Tunis ESSTT, University of Tunis [email protected] [email protected] Abstract—People with hearing disability often face multiple To address this issue, different methods and technologies barriers when attempting to interact with hearing society. geared towards deaf communication have been suggested over The lower proficiency in reading, writing and understanding the the last decades. For instance, the use of sign language spoken language may be one of the most important reasons. interpreters is one of the most common ways to ensure a Certainly, if there were a commonly accepted notation system for successful communication between deaf and hearing persons in sign languages, signed information could be provided in written direct interaction. But according to a WFD survey in 2009, 13 form, but such a system does not exist yet. SignWriting seems at countries out of 93 do not have any sign language interpreters, present the best solution to the problem of SL representation as it and in many of those countries where there are interpreters, was intended as a practical writing system for everyday there are serious problems in finding qualified candidates. communication, but requires mastery of a set of conventions The digital technologies, particularly video and avatar-based different from those of the other transcriptions systems to become a proficient reader or writer. To provide additional systems, contribute, in turn, in bridging the communication support for deaf signers to learn and use such notation, we gap. -

Sign Language Endangerment and Linguistic Diversity Ben Braithwaite

RESEARCH REPORT Sign language endangerment and linguistic diversity Ben Braithwaite University of the West Indies at St. Augustine It has become increasingly clear that current threats to global linguistic diversity are not re - stricted to the loss of spoken languages. Signed languages are vulnerable to familiar patterns of language shift and the global spread of a few influential languages. But the ecologies of signed languages are also affected by genetics, social attitudes toward deafness, educational and public health policies, and a widespread modality chauvinism that views spoken languages as inherently superior or more desirable. This research report reviews what is known about sign language vi - tality and endangerment globally, and considers the responses from communities, governments, and linguists. It is striking how little attention has been paid to sign language vitality, endangerment, and re - vitalization, even as research on signed languages has occupied an increasingly prominent posi - tion in linguistic theory. It is time for linguists from a broader range of backgrounds to consider the causes, consequences, and appropriate responses to current threats to sign language diversity. In doing so, we must articulate more clearly the value of this diversity to the field of linguistics and the responsibilities the field has toward preserving it.* Keywords : language endangerment, language vitality, language documentation, signed languages 1. Introduction. Concerns about sign language endangerment are not new. Almost immediately after the invention of film, the US National Association of the Deaf began producing films to capture American Sign Language (ASL), motivated by a fear within the deaf community that their language was endangered (Schuchman 2004). -

University of California Santa Cruz Minimal Reduplication

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ MINIMAL REDUPLICATION A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in LINGUISTICS by Jesse Saba Kirchner June 2010 The Dissertation of Jesse Saba Kirchner is approved: Professor Armin Mester, Chair Professor Jaye Padgett Professor Junko Ito Tyrus Miller Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Copyright © by Jesse Saba Kirchner 2010 Some rights reserved: see Appendix E. Contents Abstract vi Dedication viii Acknowledgments ix 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Structureofthethesis ...... ....... ....... ....... ........ 2 1.2 Overviewofthetheory...... ....... ....... ....... .. ....... 2 1.2.1 GoalsofMR ..................................... 3 1.2.2 Assumptionsandpredictions. ....... 7 1.3 MorphologicalReduplication . .......... 10 1.3.1 Fixedsize..................................... ... 11 1.3.2 Phonologicalopacity. ...... 17 1.3.3 Prominentmaterialpreferentiallycopied . ............ 22 1.3.4 Localityofreduplication. ........ 24 1.3.5 Iconicity ..................................... ... 24 1.4 Syntacticreduplication. .......... 26 2 Morphological reduplication 30 2.1 Casestudy:Kwak’wala ...... ....... ....... ....... .. ....... 31 2.2 Data............................................ ... 33 2.2.1 Phonology ..................................... .. 33 2.2.2 Morphophonology ............................... ... 40 2.2.3 -mut’ .......................................... 40 2.3 Analysis........................................ ..... 48 2.3.1 Lengtheningandreduplication. -

Assessing the Bimodal Bilingual Language Skills of Young Deaf Children

ANZCED/APCD Conference CHRISTCHURCH, NZ 7-10 July 2016 Assessing the bimodal bilingual language skills of young deaf children Elizabeth Levesque PhD What we’ll talk about today Bilingual First Language Acquisition Bimodal bilingualism Bimodal bilingual assessment Measuring parental input Assessment tools Bilingual First Language Acquisition Bilingual literature generally refers to children’s acquisition of two languages as simultaneous or sequential bilingualism (McLaughlin, 1978) Simultaneous: occurring when a child is exposed to both languages within the first three years of life (not be confused with simultaneous communication: speaking and signing at the same time) Sequential: occurs when the second language is acquired after the child’s first three years of life Routes to bilingualism for young children One parent-one language Mixed language use by each person One language used at home, the other at school Designated times, e.g. signing at bath and bed time Language mixing, blending (Lanza, 1992; Vihman & McLaughlin, 1982) Bimodal bilingualism Refers to the use of two language modalities: Vocal: speech Visual-gestural: sign, gesture, non-manual features (Emmorey, Borinstein, & Thompson, 2005) Equal proficiency in both languages across a range of contexts is uncommon Balanced bilingualism: attainment of reasonable competence in both languages to support effective communication with a range of interlocutors (Genesee & Nicoladis, 2006; Grosjean, 2008; Hakuta, 1990) Dispelling the myths….. Infants’ first signs are acquired earlier than first words No significant difference in the emergence of first signs and words - developmental milestones are met within similar timeframes (Johnston & Schembri, 2007) Slight sign language advantage at the one-word stage, perhaps due to features being more visible and contrastive than speech (Meier & Newport,1990) Another myth…. -

Critical Inquiry in Language Studies New Directions in ASL-English

This article was downloaded by: [Gallaudet University], [Adam Stone] On: 26 August 2014, At: 09:23 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Critical Inquiry in Language Studies Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/hcil20 New Directions in ASL-English Bilingual Ebooks Adam Stonea a Gallaudet University Published online: 22 Aug 2014. To cite this article: Adam Stone (2014) New Directions in ASL-English Bilingual Ebooks, Critical Inquiry in Language Studies, 11:3, 186-206, DOI: 10.1080/15427587.2014.936242 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15427587.2014.936242 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. -

Hawai'i Civil Rights Commission

,¢,..... € o F "‘‘“_ 1",,’ .. .4 Q,‘*- "0 /"I ,u' 4' ‘ .-‘$-@9359 \”,r 0 Q.-E - )‘\ ' 2‘_ ; . .J.(‘"1_.-' 1:" ._- '2-n44!‘ cull ? ‘ b mm.» HAWAI‘I CIVIL RIGHTS COMMISSION ,,.,,...,_ ‘ » $5‘. .._,,.. /\~ ,‘ ___\ ‘fife 830 PUNCHBOWL STREET, ROOM 411 HONOLULU, HI 96813 ·PHONE: 586-8636 FAX: 586-8655 TDD: 568-8692 $‘_,-"‘i£_'»*,, ,.‘-* A-_ ,a:¢j_‘f.§.......+9-.._ ~4~ -u--........~-‘Q; ,1'\n_.'9. February 24, 2021 Videoconference, 9:45 a.m. To: The Honorable Karl Rhoads, Chair The Honorable Jarrett Keohokalole, Vice Chair Members of the Senate Committee on Judiciary From: Liann Ebesugawa, Chair and Commissioners of the Hawai‘i Civil Rights Commission Re: S.B. No. 537 The Hawai‘i Civil Rights Commission (HCRC) has enforcement jurisdiction over Hawai‘i’s laws prohibiting discrimination in employment, housing, public accommodations, and access to state and state funded services. The HCRC carries out the Hawai‘i constitutional mandate that no person shall be discriminated against in the exercise of their civil rights. Art. I, Sec. 5. S.B. No. 537 would add a new section to Chapter 1 of the Hawai‘i Revised Statutes which would recognize American Sign Language (ASL) as a fully developed, autonomous, natural language with its own grammar, syntax, vocabulary and cultural heritage. Just as is the case with languages that are characteristic of ancestry or national origin, ASL is a language that is closely tied to culture and identity. Over 40 US states recognize ASL to varying degrees, from a foreign language for school credits to the official language of that state's deaf population, with several enacting legislation similar to S.B. -

CENDEP WP-01-2021 Deaf Refugees Critical Review-Kate Mcauliff

CENDEP Working Paper Series No 01-2021 Deaf Refugees: A critical review of the current literature Kate McAuliff Centre for Development and Emergency Practice Oxford Brookes University The CENDEP working paper series intends to present work in progress, preliminary research findings of research, reviews of literature and theoretical and methodological reflections relevant to the fields of development and emergency practice. The views expressed in the paper are only those of the independent author who retains the copyright. Comments on the papers are welcome and should be directed to the author. Author: Kate McAuliff Institutional address (of the Author): CENDEP, Oxford Brookes University Author’s email address: [email protected] Doi: https://doi.org/10.24384/cendep.WP-01-2021 Date of publication: April 2021 Centre for Development and Emergency Practice (CENDEP) School of Architecture Oxford Brookes University Oxford [email protected] © 2021 The Author(s). This open access article is distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-No Derivative Works (CC BY-NC-ND) 4.0 License. Table of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................................................................ 4 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 5 2. Deaf Refugee Agency & Double Displacement ............................................................................. -

The French Belgian Sign Language Corpus a User-Friendly Searchable Online Corpus

The French Belgian Sign Language Corpus A User-Friendly Searchable Online Corpus Laurence Meurant, Aurelie´ Sinte, Eric Bernagou FRS-FNRS, University of Namur Rue de Bruxelles, 61 - 5000 Namur - Belgium [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract This paper presents the first large-scale corpus of French Belgian Sign Language (LSFB) available via an open access website (www.corpus-lsfb.be). Visitors can search within the data and the metadata. Various tools allow the users to find sign language video clips by searching through the annotations and the lexical database, and to filter the data by signer, by region, by task or by keyword. The website includes a lexicon linked to an online LSFB dictionary. Keywords: French Belgian Sign Language, searchable corpus, lexical database. 1. The LSFB corpus Pro HD 3 CCD cameras recorded the participants: one for 1.1. The project an upper body view of each informant (Cam 1 and 2 in Fig- ure 1), and one for a wide-shot of both of them (Cam 3 in In Brussels and Wallonia, i.e. the French-speaking part of Figure 1). Additionally, a Sony DV Handycam was used to Belgium, significant advances have recently been made record the moderator (Cam 4 in Figure 1). The positions of of the development of LSFB. It was officially recognised the participants and the cameras are illustrated in Figure 1. in 2003 by the Parliament of the Communaute´ franc¸aise de Belgique. Since 2000, a bilingual (LSFB-French) education programme has been developed in Namur that includes deaf pupils within ordinary classes (Ghesquiere` et al., 2015; Ghesquiere` et Meurant, 2016).