Appendix One Methods of Sampling

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

36Acorn Directory of Services Neath Port Talbot.Pdf

FOREWORD Acorn was set up by a group of volunteers in August 2011 to promote positive mental health and improve the emotional health and wellbeing of individuals experiencing mental health issues in Neath Port Talbot. This directory has been produced because members of Acorn identified the need for information about services and support organisations to be easily available and in one place. It is estimated that one in four people will experience mental ill health at some point in their lifetime, so mental illness will, at one time or another impact on many of our lives, either directly or through family, friends or colleagues. It is important to be able to find the right help, support and guidance easily so we hope this directory will help to achieve this. We have tried to focus on local services, but where these don’t exist we have put together a section on national organisations, websites and help lines. If you would like to comment on the directory or contact members of Acorn please email: [email protected]. For further information, please contact Emma Jones on 01639 631 246. Michael Sheen Patron of Acorn Neath Port Talbot CONTENTS 1. Voluntary Sector 2. Advocacy Support Cymru 3. Alzheimer’s Society 4. Bipolar UK 6. Caer Las 8. Calan Dvs 9. Citizens Advice 11. Community Advice & Listening Line 12. Cruse Bereavement Care 13. Dewis 14. Free to Engage 15. Gofal 17. Hafal 18. Journeys 19. Mental Health Matters Wales 20. Mental Health & Well Being Volunteer Project 21. Mind 23. Neath Foodbank 24. Neath Port Talbot Carers Service 25. -

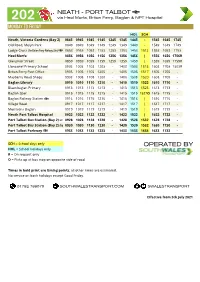

Revised Service 202 (Neath- Port Talbot)

202 NEATH - PORT TALBOT via Heol Morfa, Briton Ferry, Baglan & NPT Hospital MONDAY TO FRIDAY HOL SCH Neath, Victoria Gardens (Bay 2) 0845 0945 1045 1145 1245 1345 1445 - 1545 1645 1745 Old Road, Melyn Park 0849 0949 1049 1149 1249 1349 1449 - 1549 1649 1749 Lodge Cross (for Briton Ferry Railway Stn) 0853 0953 1053 1153 1253 1353 1453 1512 1553 1653 1753 Heol Morfa 0856 0956 1056 1156 1256 1356 1456 | 1556 1656 1756R Glanymor Street 0859 0959 1059 1159 1259 1359 1459 | 1559 1659 1759R Llansawel Primary School 0903 1003 1103 1203 - 1403 1503 1515 1603 1703 1803R Briton Ferry Post Office 0905 1005 1105 1205 - 1405 1505 1517 1605 1705 - Mayberry Road Shops 0908 1008 1108 1208 - 1408 1508 1520 1608 1708 - Baglan Library 0910 1010 1110 1210 - 1410 1510 1522 1610 1710 - Blaenbaglan Primary 0913 1013 1113 1213 - 1413 1513 1525 1613 1713 - Baglan Spar 0915 1015 1115 1215 - 1415 1515 1527O 1615 1715 - Baglan Railway Station 0916 1016 1116 1216 - 1416 1516 | 1616 1716 - Village Road 0917 1017 1117 1217 - 1417 1517 | 1617 1717 - Morrisons Baglan 0919 1019 1119 1219 - 1419 1519 | 1619 1719 - Neath Port Talbot Hospital 0922 1022 1122 1222 - 1422 1522 | 1622 1722 - Port Talbot Bus Station (Bay 2) arr 0928 1028 1128 1228 - 1428 1528 1532 1628 1728 - Port Talbot Bus Station (Bay 2) dep 0930 1030 1130 1230 - 1430 1530 1532 1630 1730 - Port Talbot Parkway 0933 1033 1133 1233 - 1433 1533 1535 1633 1733 - SCH = School days only OPERATED BY HOL = School holidays only R = On request only O = Picks up at bus stop on opposite side of road Times in bold print are timing points; all other times are estimated. -

BD22 Neath Port Talbot Unitary Development Plan

G White, Head of Planning, The Quays, Brunel Way, Baglan Energy Park, Neath, SA11 2GG. Foreword The Unitary Development Plan has been adopted following a lengthy and com- plex preparation. Its primary aims are delivering Sustainable Development and a better quality of life. Through its strategy and policies it will guide planning decisions across the County Borough area. Councillor David Lewis Cabinet Member with responsibility for the Unitary Development Plan. CONTENTS Page 1 PART 1 INTRODUCTION Introduction 1 Supporting Information 2 Supplementary Planning Guidance 2 Format of the Plan 3 The Community Plan and related Plans and Strategies 3 Description of the County Borough Area 5 Sustainability 6 The Regional and National Planning Context 8 2 THE VISION The Vision for Neath Port Talbot 11 The Vision for Individual Localities and Communities within 12 Neath Port Talbot Cwmgors 12 Ystalyfera 13 Pontardawe 13 Dulais Valley 14 Neath Valley 14 Neath 15 Upper Afan Valley 15 Lower Afan Valley 16 Port Talbot 16 3 THE STRATEGY Introduction 18 Settlement Strategy 18 Transport Strategy 19 Coastal Strategy 21 Rural Development Strategy 21 Welsh Language Strategy 21 Environment Strategy 21 4 OBJECTIVES The Objectives in terms of the individual Topic Chapters 23 Environment 23 Housing 24 Employment 25 Community and Social Impacts 26 Town Centres, Retail and Leisure 27 Transport 28 Recreation and Open Space 29 Infrastructure and Energy 29 Minerals 30 Waste 30 Resources 31 5 PART 1 POLICIES NUMBERS 1-29 32 6 SUSTAINABILITY APPRAISAL Sustainability -

Eastfield Park Northampton Management Plan

EASTFIELD PARK NORTHAMPTON MANAGEMENT PLAN Eastfield Park Management Committee May 2015 Northampton Borough Friends of Eastfield Council Park CONTENTS Page Foreword by Cllr Mike Hallam (Deputy Leader, Northampton Borough Council) iii SECTION A: Description of Eastfield Park and Surroundings A1 Introduction to Section A A1 A2 Location & Size A2 A3 Landscape, Drainage & Geology A2 A4 History A5 A5 Surrounding Areas A8 A6 Access to the Park A12 A7 Landscape & Features A15 A8 Park Facilities & Amenities A24 A9 Park Activities A27 A10 Park Wildlife & Biodiversity A30 SECTION B: Ownership and Management of Eastfield Park B1 Appendix to Section B: Eastfield Park Management Committee – B3 Terms of Reference SECTION C: The Management of Eastfield Park C1 Introduction to Section C C1 C2 Park Zonation C1 C3 The Vision for Eastfield Park C7 C4 The Heritage Appreciation Zone C8 C5 The Wildlife Appreciation Zone C9 C6 The Sport & Games Zone C12 C7 The Play and Activities Zone C13 C8 Park-wide Issues C15 C9 Five-Year Objectives C19 Appendix to Section C: Zonation maps prepared by NBC in 2007 C21 SECTION D: Consultation and Comments re Draft Management Plan D1-D2 SECTION E: Annual Action Plan 2015-16 E1-E5 i FOREWORD Northampton is very fortunate in the Parks and Open Spaces it has. Northampton has the second largest expanse of Parks and Open Spaces in the country and I would argue that it also has some of the best. In many cases, the Parks and Open Spaces we enjoy today are the legacy of our Victorian and Edwardian ancestors who saw the value in developing these spaces for all of Northampton to enjoy. -

Irish Traveller Movement in Britain

Irish Traveller Movement in Britain The Resource Centre, 356 Holloway Road, London N7 6PA Tel: 020 7607 2002 Fax: 020 7607 2005 [email protected] www.irishtraveller.org Gypsy and Traveller population in England and the 2011 Census An Irish Traveller Movement in Britain Report August 2013 About ITMB: The Irish Traveller Movement in Britain (ITMB) was established in 1999 and is a leading national policy and voice charity, working to raise the capacity and social inclusion of the Traveller communities in Britain. ITMB act as a bridge builder bringing the Traveller communities, service providers and policy makers together, stimulating debate and promoting forward-looking strategies to promote increased race equality, civic engagement, inclusion, service provision and community cohesion. For further information about ITMB visit www.irishtraveller.org.uk 1. Introduction and background In December last year, the first ever census figures for the population of Gypsies and Irish Travellers in England and Wales were released. In all 54,895 Gypsies and Irish Travellers in England and 2,785 in Wales were counted.1 While the Census population is considerably less than previous estimates of 150,000-300,000 it is important to acknowledge that tens of thousands of community members did identify as Gypsies and Travellers. In the absence of a robust figure as a comparator to the census, the ITMB undertook research to estimate a minimum population for Gypsies and Travellers in England, based on Local Authority Gypsy and Traveller Accommodation Assessments (GTAA)2 and the Department for Communities and Local Government bi-annual Caravan Count. Definitions of Gypsies and Travellers For the purposes of this report it is important to understand the varying definitions of Gypsies, Irish Travellers and other Travelling groups in official data sources. -

Weekly List of New Planning Applications. Week Ending 6 Dec 2020

Weekly list of new planning applications. Week ending 6 Dec 2020 Application No. P2020/0946 Officer Andrea Davies Type Full Plans Ward Pontardawe Date Valid 16th November 2020 Parish Pontardawe Town Council Proposal Part two storey part single storey side extension Location 20 Uplands Road Pontardawe Swansea Neath Port Talbot SA8 4AH Applicant’s Name & Address Agent’s Name & Address Mr & Mrs Andrew & Julie Mr Gwyn Evans Thomas Gwyn Evans (BC) Ltd 20 Uplands Road 3 Poplars Avenue Pontardawe Cimla Swansea Neath Neath Port Talbot SA11 3NS SA8 4AH Easting 271904 Northing 204002 ********************************************************************************** Application No. P2020/1020 Officer Christopher Davies Type Full Plans Ward Date Valid 3rd December 2020 Parish Blaenhonddan Community Council Proposal Full planning application for the development of 200 residential dwellings and associated works. Location Land At Leiros Park Bryncoch Neath Applicant’s Name & Address Agent’s Name & Address Hale Homes Mr Phil Baxter J G Hale Construction Ltd Asbri Planning Ltd. Unit 2 Unit 9 Miland Road Industrial Estate Oak Tree Court Neath Cardiff Gate Business Park SA11 1NJ Cardiff United Kingdom CF23 8RS Easting 275344 Northing 198987 ********************************************************************************** Page 1 of 8 Application No. P2020/1021 Officer Daisy Tomkins Type Full Plans Ward Coedffranc West Date Valid 16th November 2020 Parish Coedffranc Town Council Proposal Two Storey Rear Extension Location 126 Crymlyn Parc Skewen SA10 6EF Applicant’s Name & Address Agent’s Name & Address Mr & Mrs Penny Mr Cellan Jones 126 Crymlyn Parc Prime Architecture Ltd Skewen Unit 4 SA10 6EF 3 Llandeilo Road Cross Hands Llanelli SA14 6NA Easting 270749 Northing 196861 ********************************************************************************** Application No. P2020/1023 Officer Andrea Davies Type Full Plans Ward Pontardawe Date Valid 11th November 2020 Parish Pontardawe Town Council Proposal Vehicular access and parking facility with associated retaining works. -

Afan Valley Castell-Nedd Port Talbot - Dyffryn Afan

Neath Port Talbt - Afan Valley Castell-nedd Port Talbot - Dyffryn Afan LowerSOA LSOA_Name enw_AGEHI W01000900 Bryn and Cwmavon 3 Bryn a Chwmafan 3 W01000901 Bryn and Cwmavon 4 Bryn a Chwmafan 4 W01000920 Cymmer (Neath Port Talbot) 1 Cymer (Castell-nedd Port Talbot) 1 W01000921 Cymmer (Neath Port Talbot) 2 Cymer (Castell-nedd Port Talbot) 2 W01000924 Glyncorrwg Glyncorrwg Glyncorrwg W01000930 Gwynfi Gwynfi W01000945 Pelenna Pelenna Rhondda Neath Port Talbot Cynon Castell-nedd Port Talbot Taf CymmerCymmer (Neath(Neath PortPort Talbot)Talbot) 11 PelennaPelenna PelennaPelenna Gwynfi CymmerCymmer (Neath(Neath PortPort Talbot)Talbot) 22 Bridgend BrynBryn andand CwmavonCwmavon 44 Pen-y-bont ar Ogwr BrynBryn andand BrynBryn andand Communities First Cluster Area CwmavonCwmavon 33 Ardal Glwstwr Cymunedau yn Gyntaf LSOA Name & Boundary LSOA name Enw a Ffin yr AGEHI Enw AGEHI © Crown Copyright and database right 2013. Ordnance Survey 100021874. © Hawlfraint a hawliau cronfa ddata’r Goron 2013. Rhif Trwydded yr Arolwg Ordnans 100021874. 232.13-14 Cartographics/Cartograffeg Neath Port Talbt - Neath Town Castell-nedd Port Talbot - Tref Castell-nedd NeathNeath NorthNorth 33 NeathNeath NorthNorth 22 NeathNeath EastEast 11 NeathNeath EastEast 22 CoedffrancCoedffranc CentralCentral 33 NeathNeath SouthSouth 11 NeathNeath EastEast 44 NeathNeath SouthSouth 22 BritonBriton FerryFerry WestWest 11 NeathNeath EastEast 33 Neath Port Talbot Castell-nedd Port Talbot BritonBriton FerryFerry EastEast 22 LowerSOA LSOA_Name Enw_AGEHI W01000895 Briton Ferry East 2 Llansawel -

Envt1635-Lp-Ldp Reg of Alt Sites

Neath Port Talbot County Borough Council Local Development Plan 2011 –2026 Register of Alternative Sites January 2014 www.npt.gov.uk/ldp Contents 1 Register of Alternative Sites 1 2014) 1.1 Introduction 1 1.2 What is an Alternative Site? 1 (January 1.3 The Consultation 1 Sites 1.4 Register of Alternative Sites 3 1.5 Consequential Amendments to the LDP 3 Alternative of 1.6 What Happens Next? 4 1.7 Further Information 4 Register - LDP APPENDICES Deposit A Register of Alternative Sites 5 B Site Maps 15 PART A: New Sites 15 Afan Valley 15 Amman Valley 19 Dulais Valley 21 Neath 28 Neath Valley 37 Pontardawe 42 Port Talbot 50 Swansea Valley 68 PART B: Deleted Sites 76 Neath 76 Neath Valley 84 Pontardawe 85 Port Talbot 91 Swansea Valley 101 PART C: Amended Sites 102 Neath 102 Contents Deposit Neath Valley 106 Pontardawe 108 LDP Port Talbot 111 - Register Swansea Valley 120 of PART D: Amended Settlement Limits 121 Alternative Afan Valley 121 Amman Valley 132 Sites Dulais Valley 136 (January Neath 139 2014) Neath Valley 146 Pontardawe 157 Port Talbot 159 Swansea Valley 173 1 . Register of Alternative Sites 1 Register of Alternative Sites 2014) 1.1 Introduction 1.1.1 The Neath Port Talbot County Borough Council Deposit Local Development (January Plan (LDP) was made available for public consultation from 28th August to 15th October Sites 2013. Responses to the Deposit consultation included a number that related to site allocations shown in the LDP. Alternative 1.1.2 In accordance with the requirements of the Town and Country Planning (Local of Development Plan) (Wales) Regulations 2005(1), the Council must now advertise and consult on any site allocation representation (or Alternative Sites) received as soon as Register reasonably practicable following the close of the Deposit consultation period. -

Spalding Prison

SPALDING PRISON Her Majesty’s Prison for the parts of Holland and Kesteven By David Gray Officially known as “Her Majesty’s Prison for the parts of Holland and Kesteven” it adjoined the Sessions House off the Sheep Market. It was improved in 1848-52 and enlarged to have 95 separate cells, airing yards, and workshops. EARLY HISTORY OF SPALDING PRISON Although there are cells underneath the Sessions House, it was never a Prison. The Prison was in Broad Street, built in 1619 as a House Of Correction, for the ‘keeping and correcting and setting to work of rogues, vagabonds, sturdie beggars and other vagrant idle and disorderly persons’. It was used until 1834 and then demolished and the site partly used for the Methodist Church. SPALDING PRISON IN THE SHEEP MARKET A new Prison was built next to the Sessions House in the Sheep Market, which was completed in 1836. It had all the conveniences, a human treadmill for the prisoners to walk on to grind their own flour, lots of cells for solitary confinement and 48 sleeping cells and a Chapel. Human Treadmill similar to the one that would have been used in the Prison Executions took place publicly in Spalding Market Place. The last man to be hung was in 1742, and his body afterwards “Gibbeted”, (hung in chains) on Vernat’s Bank. Spalding also used Stocks (heavy timber frame with holes for confining the ankles and sometimes the wrists) and a Pillory (a device made of a wooden or metal framework erected on a post, with holes for securing the head and hands) , and a Tumbril (a two- wheeled cart that tipped up, used to transport prisoners) . -

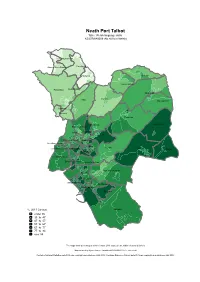

Neath Port Talbot Table: Welsh Language Skills KS207WA0009 (No Skills in Welsh)

Neath Port Talbot Table: Welsh language skills KS207WA0009 (No skills in Welsh) Lower Brynamman Cwmllynfell Gwaun−Cae−Gurwen Ystalyfera Onllwyn Seven Sisters Pontardawe Godre'r graig Glynneath Rhos Crynant Blaengwrach Trebanos Allt−wen Resolven Aberdulais Glyncorrwg Bryn−coch North Dyffryn Cadoxton Tonna Bryn−coch South Neath North Coedffranc North Cimla Pelenna Cymmer Coedffranc Central Neath East Gwynfi Neath South Coedffranc West Briton Ferry West Briton Ferry East Bryn and Cwmavon Baglan Aberavon Sandfields West Port Talbot Sandfields East Tai−bach %, 2011 Census Margam under 35 35 to 47 47 to 57 57 to 67 67 to 77 77 to 84 over 84 The maps show percentages within Census 2011 output areas, within electoral divisions Map created by Hywel Jones. Variables KS208WA0022−27 corrected Contains National Statistics data © Crown copyright and database right 2013; Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2013 Neath Port Talbot Table: Welsh language skills KS207WA0010 (Can understand spoken Welsh only) Lower Brynamman Gwaun−Cae−Gurwen Cwmllynfell Onllwyn Ystalyfera Seven Sisters Pontardawe Godre'r graig Glynneath Rhos Crynant Blaengwrach Allt−wen Trebanos Resolven Aberdulais Bryn−coch North Glyncorrwg Dyffryn Cadoxton Tonna Coedffranc North Bryn−coch South Neath North Coedffranc Central Neath South Pelenna Gwynfi Cimla Cymmer Neath East Briton Ferry West Coedffranc West Briton Ferry East Bryn and Cwmavon Baglan Sandfields West Aberavon Port Talbot Sandfields East Tai−bach %, 2011 Census Margam under 4 4 to 5 5 to 7 7 to 9 9 to 12 12 to 14 over 14 The maps show percentages within Census 2011 output areas, within electoral divisions Map created by Hywel Jones. -

Annual Report & Accounts 2010

Annual Report & Accounts 2010 The Hospital Broadcasting Service Registered as a Charity Suite 444 SC009138 Baltic Chambers 50 Wellington Street Phone : 0141 - 221 - 4043 Glasgow Fax : 0141 - 204 - 0404 G2 6HJ http://www.hbs.org.uk Annual Report & Accounts 2010 The Hospital Broadcasting Service Executive Committee Members Chairman Niall Anderson Treasurer Stephen Boardman Programme Director John Gilbertson (to 25/04/10) Niall Anderson (from 25/04/10 - acting ) Technical Director David Bannerman Annual Post Holders Eileen Heuston Peggy Mack Charlie Murphy (to 25/04/10) Isabel Vincent Cheryl Ward (from 25/04/10 to 13/10/10) Co-Opted Member Charlie Murphy (from 18/05/10) Charity Number SC009138 Principal Address Suite 444 Baltic Chambers 50 Wellington Street Glasgow G2 6HJ Bankers The Royal Bank of Scotland 1 Roadside The Village Cumbernauld G67 2SS Signed on behalf of the Executive Committee Niall Anderson Stephen Boardman Chairman Treasurer 20 th March 2011 20 th March 2011 Accounts independently examined Craig McDougall Commercial Controller, Victoria Infirmary Radio 20 th March 2011 Page 1 Annual Report & Accounts 2010 The Hospital Broadcasting Service Executive Committee’s Report The Executive Committee of The Hospital Broadcasting Service are pleased to submit their report and accounts for the year 1st January to 31st December 2010. The Hospital Broadcasting Service (also known On-Air as ‘HBS’) is registered with the Office of the Scottish Charity Regulator and governed by a Constitution. This report and attached accounts have been prepared in accordance with the terms of the Charities and Trustee Investment (Scotland) Act 2005 and Charities Accounts (Scotland) Regulations 2006. -

Additional Information on Flying Start from the Deputy

Table 1: Estimate of number of children aged 0 to 3 in income benefit households in each Welsh LSOA, sorted by the estimated proportion of 0-3s in income benefits households for each Local Authority cumulative estimated total of 0-3s number of 0- Number of 0- in Income proportion 3s in 3s from Benefit cumulative of 0-3s in Lower Income Small Area Households total of 0-3s, Income Super Office of National Benefit Population by Local by Local Benefit Output Area Statistics Name Lower Super Output Area Name Local Authority Name Households Estimate Authority Authority Households W01001457 Blaenau Gwent 004D Ebbw Vale North 2 Blaenau Gwent 60 80 60 80 71.6% W01001473 Blaenau Gwent 003B Sirhowy 2 Blaenau Gwent 40 65 100 145 64.1% W01001479 Blaenau Gwent 006D Tredegar Central and West 2 Blaenau Gwent 50 85 150 230 58.7% W01001459 Blaenau Gwent 007D Ebbw Vale South 1 Blaenau Gwent 25 50 175 280 50.2% W01001453 Blaenau Gwent 008D Cwmtillery 1 Blaenau Gwent 40 80 215 365 48.9% W01001469 Blaenau Gwent 005F Nantyglo 3 Blaenau Gwent 30 65 245 430 47.7% W01001471 Blaenau Gwent 001E Rassau 2 Blaenau Gwent 35 75 280 505 47.3% W01001441 Blaenau Gwent 001B Beaufort 2 Blaenau Gwent 30 65 315 570 46.8% W01001447 Blaenau Gwent 002B Brynmawr 2 Blaenau Gwent 50 110 365 680 45.4% W01001480 Blaenau Gwent 003E Tredegar Central and West 3 Blaenau Gwent 25 55 385 735 43.7% W01001474 Blaenau Gwent 003C Sirhowy 3 Blaenau Gwent 20 50 410 785 42.0% W01001456 Blaenau Gwent 004C Ebbw Vale North 1 Blaenau Gwent 25 60 430 845 41.3% W01001466 Blaenau Gwent 009C Llanhilleth