Crossing Borders: Feminism, Intersectionality, and Citizenship

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction: a Global Approach to Reproductive Justice—Psychosocial and Legal Aspects and Implications

William & Mary Journal of Race, Gender, and Social Justice Volume 20 (2013-2014) Issue 1 William & Mary Journal of Women and the Law: 2013 Special Issue: Reproductive Article 2 Justice December 2013 Introduction: A Global Approach to Reproductive Justice—Psychosocial and Legal Aspects and Implications Joan C. Chrisler Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmjowl Part of the Human Rights Law Commons, Law and Gender Commons, and the Women's Health Commons Repository Citation Joan C. Chrisler, Introduction: A Global Approach to Reproductive Justice—Psychosocial and Legal Aspects and Implications, 20 Wm. & Mary J. Women & L. 1 (2013), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmjowl/vol20/iss1/2 Copyright c 2013 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmjowl INTRODUCTION: A GLOBAL APPROACH TO REPRODUCTIVE JUSTICE—PSYCHOSOCIAL AND LEGAL ASPECTS AND IMPLICATIONS JOAN C. CHRISLER, PH.D.* INTRODUCTION I. TOPICS COVERED BY THE REPRODUCTIVE JUSTICE MOVEMENT II. WHY REPRODUCTIVE JUSTICE IS DIFFICULT TO ACHIEVE III. WHY REPRODUCTIVE JUSTICE IS IMPORTANT IV. WHAT WE CAN DO IN THE STRUGGLE FOR REPRODUCTIVE JUSTICE INTRODUCTION The term reproductive justice was introduced in the 1990s by a group of American Women of Color,1 who had attended the 1994 Inter- national Conference on Population and Development (ICPD), which was sponsored by the United Nations and is known as “the Cairo conference.” 2 After listening to debates by representatives of the gov- ernments of UN nation states about how to slow population growth and encourage the use of contraceptives and the extent to which women’s reproductive rights could/should be guaranteed, the group realized, as Loretta Ross later wrote, that “[o]ur ability to control what happens to our bodies is constantly challenged by poverty, racism, en- vironmental degradation, sexism, homophobia, and injustice . -

Transnational, Third World, and Global Feminisms

1 Transnational, Third World, and Global Feminisms Ranjoo S. Herr Encyclopedia of Race and Racism (second ed.). Routledge, 2013 Check with the original to verify italics Third world, transnational, and global feminisms focus on the situation of racial-ethnic women originating from the third world (or the South), whether or not they reside in the first world (or the North or West). This entry refers to these women as ―third world women.‖ Most second- wave white feminisms in the West—liberal, radical, psychoanalytic, or ―care-focused‖ feminisms (Tong 2009)—have assumed that women everywhere face similar oppression merely by virtue of their sex/gender. Global feminism as it first emerged in the 1980s was largely a global application of this white feminist outlook. Third world and transnational feminisms emerged in the 1980s and early 1990s to challenge this white feminist assumption. These feminisms are predicated on the premise that women‘s oppression diverges globally due to not only gender, but also race, class, ethnicity, religion, and nation. Therefore, third world women suffer from multiple forms of oppression qualitatively different from the gender oppression experienced by middle-class white women in the West. Third world and transnational feminisms are distinct, however, not only in their origins and outlooks, but also in their goals and priorities. This entry begins by examining the genealogies of these feminisms, in the process of which their differences will be identified. It then explains four main characteristics that these feminisms share. After reviewing some instances of third world, transnational, and global feminist activities, the entry concludes by suggesting a way to resolve a potential conflict between the local and the universal facing third world, transnational, and global feminists. -

TRANSNATIONAL FEMINIST ITINERARIES NEXT WAVE NEW DIRECTIONS in WOMEN’S STUDIES a Series Edited by Inderpal Grewal, Caren Kaplan, and Robyn Wiegman TRANSNATIONAL

TRANSNATIONAL Ashwini Tambe and Millie Thayer, editors FEMINIST Situating Theory and Activist Practice ITINERARIES TRANSNATIONAL FEMINIST ITINERARIES NEXT WAVE NEW DIRECTIONS IN WOMEN’S STUDIES A series edited by Inderpal Grewal, Caren Kaplan, and Robyn Wiegman TRANSNATIONAL Situating Theory FEMINIST ITINERARIES and Activist Practice Edited by ashwini tambe and millie thayer DUKE UNIVERSITY PRESS DURHAM AND LONDON 2021 © 2021 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of Amer i ca on acid- free paper ∞ Proj ect editor: Lisa Lawley Designed by Aimee C. Harrison Typeset in Minion Pro and ITC Franklin Gothic by Westchester Publishing Services Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Tambe, Ashwini, editor. | Thayer, Millie, editor. Title: Transnational feminist itineraries : situating theory and ac tivist practice / Ashwini Tambe and Millie Thayer, eds. Other titles: Next wave (Duke University Press) Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2021. | Series: Next wave | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: lccn 2020051607 (print) lccn 2020051608 (ebook) isbn 9781478013549 (hardcover) isbn 9781478014430 (paperback) isbn 9781478021735 (ebook) Subjects: lcsh: Feminist theory. | Transnationalism. | National- ism and feminism. | Intersectionality (Sociology) Classification: lcc hq1190 .t739 2021 (print) | lcc hq1190 (ebook) | ddc 305.42— dc23 lc rec ord available at https:// lccn . loc . gov / 2020051607 lc ebook rec ord available at https:// lccn . loc . gov / 2020051608 -

Word and Image

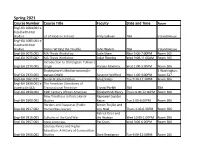

Word and Image Topics in Literary Theory II: Digital Engl-GA 2958.002 Literary Studies David Hoover Thurs 6:20-9:20PM TBA Gabriela Basterra & PUBHM-GA 1001 Theorizing Public Humanities Helga Tawil-Souri TBA TBA Michael Beckerman PUBHM-GA 1101 Practicing Public Humanities and Sophie Gonick TBA TBA Spring 2021 Course Descriptions Engl.GA 2270.001 Introduction to Old English: Tolkien's Origin Haruko Momma This course has two purposes: first, to introduce students to Old English language and literature and also to the culture and history in which this language was prospered; second, to use Old English as an entry point to explore J. R. R. Tolkien’s work, both academic and creative. This course will be divided into three parts. In the first part, we will go over basic Old English grammar and read, with the help of translations, passages from Old English prose including The Apollonius of Tyre, which Tolkien edited in 1958. Since Old English is noticeably different from its descendant Modern English, it needs to be approached almost as a foreign language: students will therefore be encouraged to memorize basic grammatical endings and core vocabulary (but not as intensely as Tolkien did). We will use Henry Sweet’s Anglo-Saxon Primer and Anglo-Saxon Reader, two textbooks that Tolkien used to study Old English as a student, although there will be contemporary teaching materials to supplement them. In the second part, we will read shorter Old English poems while studying somewhat more advanced grammar, syntax, and versification. We will be reading Tolkien’s writing related to these poetic texts: for instance, we will read The Battle of Maldon, a poem about the English army’s defeat by the Viking invaders, side by side with Tolkien’s The Homecoming of Beorhtnoth Beorhthelm’s Son, which is a fascinating dramatization of the poem; we will read some of the Advent Lyrics and discuss Tolkien’s use of one of the lyrics in The Lord of the Rings. -

Unthinking the Transnational

WGSS 494TI Integrative Experience Capstone: Professor Alex Deschamps Spring 2013 Unthinking the Transnational – Political Tue & Thu 2:30 – 3:45 pm Schedule#: 24813 Activism, Geographies of Development and Bartlett 274 Power Office: Bartlett 7B » Wednesdays 2:30 – 4:00 pm & by appointment Telephone: 545-1958 0r 57-0842 ▪ Email: [email protected] E-Reserves: wgss494ti▪ Course Description This course is about the framework of transnational women’s and gendered activisms and scholarship. We will survey the field of transnational feminist research and praxis, locating structures of power, practices of resistance, and the geographies of development at work in a range of theories and social movements. The course will not only examine the implementation of feminist politics and projects that have sought to ensure some measurable social, cultural, and economic changes, but also explore the ways conceptions of the ‘global’ and ‘transnational’ have informed these efforts. Students will have the opportunity to assess which of these practices can be applicable, transferable, and/or travel on a global scale. We will focus not only on the agency of individuals, but also on the impact on people’s lives and their communities as they adopt strategies to improve material, social, cultural, and political conditions of their lives. The relationship between academic theorizing and community organizing for productive social and political change is a vital, complex and ever-changing source of feminist inquiry. We will build on this relationship by interweaving activist social and political work with the theoretical interventions as well as feminist research methodology. We hope students will gain a fuller picture of the ways the framework of the “transnational” has informed and transformed theoretical, social and political spaces in both productive and problematic ways. -

A Transnational Feminist Perspective of US Health Coloniality

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 1-1-2019 Dominating the Disease: A Transnational Feminist Perspective of U.S. Health Coloniality Jessica Ann Johnson University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd Part of the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons Recommended Citation Johnson, Jessica Ann, "Dominating the Disease: A Transnational Feminist Perspective of U.S. Health Coloniality" (2019). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1586. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/1586 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. Dominating the Disease: A Transnational Feminist Perspective of U.S. Health Coloniality __________ A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of Social Sciences University of Denver __________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy __________ by Jessica A. Johnson June 2019 Advisor: Dr. Bernadette Calafell, PhD ©Copyright by Jessica A. Johnson 2019 All Rights Reserved Author: Jessica A. Johnson Title: Dominating the Disease: A Transnational Feminist Perspective of U.S. Health Coloniality Advisor: Dr. Bernadette Calafell, PhD Degree Date: June 2019 Abstract HIV has been a pandemic since the 1980s with 70 million people infected since the beginning, about 35 million people have died of complications resulting from HIV, and an estimated 36.9 million people living with HIV in 2017 (WHO, “HIV and AIDS”). -

Women's Human Rights and Migration: Sex-Selective Abortion Laws In

University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School Penn Law: Legal Scholarship Repository Faculty Scholarship at Penn Law 2018 Women’s Human Rights and Migration: Sex-Selective Abortion Laws in the United States and India Rangita de Silva de Alwis University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, Human Rights Law Commons, Law and Gender Commons, Law and Society Commons, Public Law and Legal Theory Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Repository Citation de Silva de Alwis, Rangita, "Women’s Human Rights and Migration: Sex-Selective Abortion Laws in the United States and India" (2018). Faculty Scholarship at Penn Law. 1986. https://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/faculty_scholarship/1986 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Penn Law: Legal Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship at Penn Law by an authorized administrator of Penn Law: Legal Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Images such as the veiled women, the powerful mother, the chaste virgin, the obedient wife, and so on… exist in universal, ahistorical splendor, setting in motion a colonialist discourse that exercises a very specific power in defining, coding, and maintaining existing First/Third World connections. (Chandra Talpade Mohanty, Feminism Without Borders 41) Book Review 1 Rangita de Silva de Alwis, Associate Dean of International Affairs, University of Pennsylvania Law School Sital Kalantry’s Women’s Human Rights and Migration: Sex Selective Abortion Laws in the United States in India, addresses a long-existing gap in feminist theory at the intersection of a migrant woman’s experience and culturally motivated reproductive decisions. -

Transnational Feminisms Syllabus 4Credits

WGSS 585: TRANSNATIONAL FEMINISMS Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Oregon State University (4 credits) (this course will meet for approximately four hours each week) Dr. Patti Duncan 266 Waldo Hall Office Hours: by appointment [email protected] (This course is intended for graduate students in Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies.) __________________________________________________________________________________________________ CATALOGUE DESCRIPTION In this interdisciplinary graduate seminar, students will be introduced to themes and theoretical principles of transnational feminisms, with special emphasis placed on feminist movements of the global South. We will explore colonialism, globalization, nation-building, representation, global economies, militarism, human rights, and politics of gender, race, class, sexuality, and nation. COURSE DESCRIPTION What constitutes transnational feminism(s)? How do members of communities in various parts of the world understand and articulate their relationships to feminism and feminist organizing? How do activists in specific cultural contexts resist multiple forms of oppression and transform understandings of gender, citizenship, and nation? In this graduate seminar, students will be introduced to various themes and theoretical principles of transnational feminisms, with special emphasis placed on feminist movements of the global South. Examining the ways in which women of the global South and feminist movements have been imagined, constructed, regulated, and represented in various -

Transnational Legal Feminisms: Challenges and Opportunities Sital Kalantry†

\\jciprod01\productn\C\CIN\52-1\CIN106.txt unknown Seq: 1 19-FEB-20 15:53 Transnational Legal Feminisms: Challenges and Opportunities Sital Kalantry† Introduction The Cornell International Law Journal’s annual symposium held in March 2018 was entitled “Transnational Legal Feminisms: Challenges and Opportunities.” In this essay, I reflect on what “Transnational Legal Femi- nisms” means and what potential challenges and opportunities it presents. Feminist legal scholars and lawyers are operating in an increasingly inter- connected world today, where popular feminist perspectives and scholarly theories, capital, people, and information move rapidly from country to country. The #MeToo movement is an example of the transnationalization of feminist ideas and legal solutions. Gaining momentum through social media in the United States, the movement against sexual assault and sexual harassment migrated around the world.1 This transnational movement of legal solutions is not without its problems. For example, a group of promi- nent French feminists objected to the French version of the #MeToo move- ment, claiming it is based on a puritanical understanding of relations between men and women.2 According to those feminists, more overt male sexual behavior and flirtation is more acceptable in French society than in American society.3 What may be considered sexual harassment or assault by American definitions, the French feminists argue, is not the same by † Clinical Professor of Law, Cornell Law School. I would like to thank the participants in the Cornell International Law Journal Symposium in March 2018. I appreciate the hard work of the symposium editors in organizing this innovative conference and for Gianni Pizzitola for his patience and editing assistance in this essay. -

Transnational Feminist Crossings: on Neoliberalism and Radical Critique Author(S): Chandra Talpade Mohanty Source: Signs, Vol

Transnational Feminist Crossings: On Neoliberalism and Radical Critique Author(s): Chandra Talpade Mohanty Source: Signs, Vol. 38, No. 4, Intersectionality: Theorizing Power, Empowering Theory (Summer 2013), pp. 967-991 Published by: The University of Chicago Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/669576 Accessed: 04-04-2017 03:00 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Signs This content downloaded from 133.30.212.88 on Tue, 04 Apr 2017 03:00:52 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms Chandra Talpade Mohanty Transnational Feminist Crossings: On Neoliberalism and Radical Critique hat happens to feminist scholarship and theory in our neoliberal aca- W demic culture? Have global and domestic shifts in social movement ac- tivism and feminist scholarly projects depoliticized antiracist, women- of-color, and transnational feminist intellectual projects? By considering how my own work has traveled, and what has been lost ðand foundÞ in translation into various contexts, I offer some thoughts about the effects of neoliberal, national-security-driven geopolitical landscapes and postmodern intellectual framings of transnational, intersectional feminist theorizing and solidarity work. -

Gender Equality?: a Transnational Feminist Analysis of the Un

GENDER EQUALITY?: A TRANSNATIONAL FEMINIST ANALYSIS OF THE UN HEFORSHE CAMPAIGN AS A GLOBAL “SOLIDARITY” MOVEMENT FOR MEN _______________________________________ A Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia _______________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts _____________________________________________________ by JAIME HENRY-WHITE Dr. Cristina Mislán, Thesis Supervisor MAY 2015 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the thesis entitled GENDER EQUALITY?: A TRANSNATIONAL FEMINIST ANALYSIS OF THE UN HEFORSHE CAMPAIGN AS A GLOBAL “SOLIDARITY” MOVEMENT FOR MEN presented by Jaime Henry-White, a candidate for the degree of master of arts, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Professor Cynthia Frisby Professor Debra Mason Professor Cristina Mislán Professor Tola Pearce ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS “Wise shall be the bearers of light.” Hundreds have walked under the Journalism School archway at the University of Missouri and read this quote etched in its stone. I, too, have seen this quote hundreds of times while heading to the quad or rushing, yet again, late to class. But every time, it strikes a chord. This place and its people, who tirelessly work to train the journalists of tomorrow, epitomize wisdom. Professors here not only teach students to be storytellers. They teach us to be better human beings, to constantly evolve and to pursue the truth undeterred. They teach us to imagine, to fail, to live. I almost didn’t come here. But, somehow, I did. And how truly lucky I am. First things first, I have to thank the photojournalism department, my original home at Mizzou and a place with so much heart. -

Transnational Feminism in Film and Media 1St Edition Pdf, Epub, Ebook

TRANSNATIONAL FEMINISM IN FILM AND MEDIA 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Katarzyna Marciniak | 9780230338142 | | | | | Transnational Feminism in Film and Media 1st edition PDF Book Forward Looking Stories Fujifilm innovation has always driven the company forward. Open Innovation Fujifilm's open innovation is about listening to the customer and innovating together. Revolutionary techniques and a wealth of experience have enabled high-precision and high-resolution mammography. Radical Philosophy A terrific book. In celebration of the opening of the Elizabeth A. The second wave was increasingly theoretical, based on a fusion of neo-Marxism and psycho-analytical theory, and began to associate the subjugation of women with broader critiques of patriarchy, capitalism, normative heterosexuality, and the woman's role as wife and mother. Prerequisites: Critical Approaches or Feminist Theory or permission of instructor. Boryana Rossa Bulgarian, b. X-Photographers Online Gallery. Our point of departure will be the precariousness of embodied existence, in which precarity is understood as both an existential condition and as the socially uneven culmination of neoliberal political and economic trends. Reprints and Permissions. Marciniak A. Activity List for Sustainability. Be Curious — Leeds, Leeds. At once material and symbolic, our bodies exist at the intersections of multiple competing discourses, including the juridical, the techno-scientific, and the biopolitical. Here the artist transposes the borderlines of Germany and Africa onto her stomach by way of a stencil and exposure to the sun. Celebrating the Next Twinkling Praznuvane na sledvascia mig , Here, women's problematic positioning in relation to national and religious identities, as well as to global power structures is the focus.