City Research Online

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: ROYAL SUBJECTS

ABSTRACT Title of dissertation: ROYAL SUBJECTS, IMPERIAL CITIZENS: THE MAKING OF BRITISH IMPERIAL CULTURE, 1860- 1901 Charles Vincent Reed, Doctor of Philosophy, 2010 Dissertation directed by: Professor Richard Price Department of History ABSTRACT: The dissertation explores the development of global identities in the nineteenth-century British Empire through one particular device of colonial rule – the royal tour. Colonial officials and administrators sought to encourage loyalty and obedience on part of Queen Victoria’s subjects around the world through imperial spectacle and personal interaction with the queen’s children and grandchildren. The royal tour, I argue, created cultural spaces that both settlers of European descent and colonial people of color used to claim the rights and responsibilities of imperial citizenship. The dissertation, then, examines how the royal tours were imagined and used by different historical actors in Britain, southern Africa, New Zealand, and South Asia. My work builds on a growing historical literature about “imperial networks” and the cultures of empire. In particular, it aims to understand the British world as a complex field of cultural encounters, exchanges, and borrowings rather than a collection of unitary paths between Great Britain and its colonies. ROYAL SUBJECTS, IMPERIAL CITIZENS: THE MAKING OF BRITISH IMPERIAL CULTURE, 1860-1901 by Charles Vincent Reed Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2010 Advisory Committee: Professor Richard Price, Chair Professor Paul Landau Professor Dane Kennedy Professor Julie Greene Professor Ralph Bauer © Copyright by Charles Vincent Reed 2010 DEDICATION To Jude ii ACKNOWLEGEMENTS Writing a dissertation is both a profoundly collective project and an intensely individual one. -

1 Everyday Ontological Security

Everyday Ontological Security: Emotion and Migration in British Soaps Abstract Work on affect has made significant contributions to how IR scholars understand high politics of international affairs, capturing political reactions to the horrific, the spectacular and the exceptional. However, the turn to affect has been less inclined to offer comprehensive insight into the importance of emotion in banal or everyday international politics. The theory of ontological security can offer such insight as it attends to experiences of the everyday, particularly through the discursive production of identity. Identity might be disrupted at moments of spectacular or exceptional events that call it to question, but is equally made and remade in the discursive production of everyday life. This research focuses on the latter, analysing the reproduction of the international in the everyday through the vehicle of British soaps Coronation Street and Emmerdale, both of which introduced storylines about migrant workers in the late 2000s. British soaps are designed to be culturally proximate and incorporate didactic messages. Analysis of soaps offers a layered and intersectional view of emotional reactions to international migration at the level of an abstracted individual and the level of the nation-as-viewer. Work on affect has made significant contributions to how IR scholars understand high politics of international affairs, capturing political reactions to the horrific, the spectacular and the exceptional (Auchter 2014, Fierke 2012, Hutchinson and Bleiker 2014). However, the turn to affect has been less inclined to offer comprehensive insight into the importance of emotion in banal or everyday international politics. Feminists in IR are of course the exception to this rule, variously focusing on the importance of emotion in encounters with international phenomena (Stern 1998, Ackerley and True 2008, MacKenzie 2011, Dauphinee 2013). -

14Th Amendment US Constitution

FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT RIGHTS GUARANTEED PRIVILEGES AND IMMUNITIES OF CITIZENSHIP, DUE PROCESS AND EQUAL PROTECTION CONTENTS Page Section 1. Rights Guaranteed ................................................................................................... 1565 Citizens of the United States ............................................................................................ 1565 Privileges and Immunities ................................................................................................. 1568 Due Process of Law ............................................................................................................ 1572 The Development of Substantive Due Process .......................................................... 1572 ``Persons'' Defined ................................................................................................. 1578 Police Power Defined and Limited ...................................................................... 1579 ``Liberty'' ................................................................................................................ 1581 Liberty of Contract ...................................................................................................... 1581 Regulatory Labor Laws Generally ...................................................................... 1581 Laws Regulating Hours of Labor ........................................................................ 1586 Laws Regulating Labor in Mines ....................................................................... -

Cardboard Citizens' Critically Acclaimed Hit Cathy

UNDER EMBARGO UNTIL THURSDAY, 20th at 00.01 CARDBOARD CITIZENS’ CRITICALLY ACCLAIMED HIT CATHY RETURNS FOR EDINBURGH FESTIVAL FRINGE RUN CARDBOARD CITIZENS DEBUTS AT THE PLEASANCE ON THE EDINBURGH FESTIVAL FRINGE WITH ITS HIT PRODUCTION CATHY, INSPIRED BY CATHY COME HOME WRITTEN BY ALI TAYLOR AND DIRECTED BY ADRIAN JACKSON CATHY WAS RESEARCHED IN COLLABORATION WITH HOMELESSNESS CHARITY, SHELTER INTERACTIVE LEGISTLATIVE THEATRE STYLE WILL ALLOW AUDIENCES TO VOICE THEIR OPINIONS ON THE STATE OF HOUSING IN THE UK TICKETS NOW ON SALE AT WWW.EDFRINGE.COM or WWW.PLEASANCE.CO.UK IMAGES AVAILABLE HERE (USERNAME: Cardboard PASSWORD: Citizens) Following its hugely successful UK tour, acclaimed theatre company Cardboard Citizens comes to the Edinburgh Festival Fringe for the first time with its critically acclaimed production Cathy, featuring the original cast. Cathy premiered last autumn following Cardboard Citizens one-off theatrical re-staging of Ken Loach’s seminal work Cathy Come Home at the Barbican. Inspired by the iconic film, award-winning playwright Ali Taylor’s (Cotton Wool, OVERSPILL) new play continued Cardboard Citizens exploration of the state of housing and homelessness. The powerful and emotive show, which transfers to the Edinburgh Festival Fringe in Cardboard Citizens’ 25th anniversary year, is directed by Cardboard Citizens Artistic Director Adrian Jackson and explores how life might be for a Cathy today. Based on true stories, this timely reflection looks at the social and personal impact of spiralling housing costs and the challenges of forced relocation out of city centres experienced by many people on council waiting lists. While the UK tour featured a Forum Theatre section, following the performance of the play, Edinburgh audiences will experience a similar style of interactive theatre called Legislative Theatre. -

A Safe Environment for Children Qualitative and Quantitative Findings

A safe environment for children Qualitative and quantitative findings September 2005 1 Contents Section Page Foreword 3 Executive summary 4 Background 7 Part 1: Qualitative research 1.1 Introduction 9 1.2 Detailed summary 10 1.3 The context of a safe environment 14 1.4 The influence of soap operas 22 1.5 Attitudes to regulation 28 Appendix A: the sample 30 Part 2: Quantitative research 2.1 Introduction 32 2.2 Which media are of most concern? 33 2.3 Which age of children are felt to be at risk? 35 2.4 Levels of concern about pre-watershed content 36 2.5 Types of concern about pre-watershed content 40 2.6 Opinions about the purpose of soap operas 42 2.7 Views on who should be responsible 44 2.8 Parental control over children’s viewing 45 Appendix B: who watches soap operas 46 2 Foreword Section 319 (1) of the Communications Act 2003 (“The Act”) requires Ofcom to set a Code which contains standards for the content of television and radio services. The Ofcom Broadcasting Code, took effect on 25 July 20051. The Code applies to all broadcasters regulated by Ofcom, with certain exceptions in the case of the BBC (Sections Five, Six, Nine and Ten) and S4C (part of Section Six). The Act requires that those under eighteen should be protected and Section One of the Broadcasting Code concerns the protection of the under-eighteens. It contains a number of rules regarding scheduling and content information (Rules 1.1 to 1.7) and specific rules regarding drugs, smoking, solvents and alcohol, violence and dangerous behaviour, offensive language and sex ( Rules 1.10 to 1.17). -

How Do British Teenagers Aged 16-18 Receive and Interpret Alcohol Messages Portrayed in the British Soap Opera Eastenders?

HOW DO BRITISH TEENAGERS AGED 16-18 RECEIVE AND INTERPRET ALCOHOL MESSAGES PORTRAYED IN THE BRITISH SOAP OPERA EASTENDERS? ADILAID BHEBHE A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Nottingham Trent University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy FEBRUARY 2021 "This work is the intellectual property of the author, Adilaid Bhebhe. You may copy up to 5% of this work for private study, or personal, non-commercial research. Any re-use of the information contained within this document should be fully referenced, quoting the author, title, university, degree level and pagination. Queries or requests for any other use, or if a more substantial copy is required, should be directed in the owner of the Intellectual Property Rights" ABSTRACT Reception of media texts by audiences continues to occupy a fundamental position in the field of media studies, particularly in the face of the technological advances characterising the contemporary television viewing environment. Through a qualitative approach, this study investigates the reception of health communication messages, in the form of harmful drinking storylines portrayed in the British soap opera EastEnders, by sixteen to eighteen-year olds, in a multi-media reception environment. This is in the context of the socio-economic and health burden imposed on the British society by harmful drinking particularly by this age-group. The study takes a broad approach to reception and as such investigates the main moments of the circuit of culture for a holistic understanding of meaning-making processes by young people. To this end focus group interviews and long interviews were used to obtain views of young people and health experts while EastEnders producer and health organisations involved in the creation of alcohol storylines were also interviewed. -

Construction of Contemporary Women in Soap Operas

Commentaries Global Media Journal – Indian Edition/ISSN 2249-5835 Sponsored by the University of Calcutta/ www.caluniv.ac.in Summer Issue / June 2012 Vol. 3/No.1 CONSTRUCTION OF CONTEMPORARY WOMEN IN SOAP OPERAS Dr. Aaliya Ahmed Senior Assistant Professor, Media Education Research Centre University of Kashmir, Hazratbal, Srinagar-190006, J&K, India Website: http://www.kashmiruniversity.net Email: [email protected] and Ms. Malik Zahra Khalid Senior Assistant Professor, Media Education Research Centre University of Kashmir, Hazratbal, Srinagar-190006, J&K, India Website: http://www.kashmiruniversity.net Email: [email protected] Abstract: Women are an important component of our society. The issue of the empowerment of women is a matter of serious concern and thought. Efforts are being made to establish the significant role that she can play to uplift herself, her family and the society at large. Women play an important role to make society progressive and lead it toward development. They are vital assets of a vibrant society required for national development. There can be no denying the fact that women play a key role in shaping the society provided they are given the right and equal opportunities at the right time. The efficacy of television as a means of communication is very high vis-à-vis women. Television has an important role in shaping and influencing their views, opinions and attitude. Soap operas are a very popular genre and have a huge viewership. Keywords: Empowerment, women. Soap-operas, Doordarshan, social change, ideology Defining Empowerment The concept of empowerment is heuristic in understanding the complex constraints in Third World development. -

Radio Soap Operas for Peacebuilding a Guide Part 2

Radio Soap Operas for Peacebuilding a guide Part 2 Jon Hargreaves and Francis Rolt Contents How to use this guidebook ......................................................................1-26 Facilitators’ Manual ................................................................................1-174 Background Briefings for Facilitators.....................................................1-48 Documents for Facilitators.......................................................................1-17 Handouts for Participants ........................................................................1-14 Participants’ Workbook..........................................................................1-117 HOW TO USE THIS GUIDEBOOK Radio soap operas for Peacebuilding – Part 2 1 Table of contents I. FACILITATOR’S GUIDE.......................................................................3 II. CHECKLISTS FOR PLANNING YOUR COURSE..............................10 III. WELCOME KIT...................................................................................17 IV. WELCOME LETTER...........................................................................18 V. SUGGESTED PROGRAMME SCHEDULE ........................................20 VI. DOCUMENTS AVAILABLE................................................................21 VII. COURSE EVALUATION REPORT SHEET........................................24 ADMINISTRATION FOR FACILITATORS @ HCR/SFCG 2 I. FACILITATOR’S GUIDE 1. INTRODUCTION This manual is for the facilitators of a course to train people to write serial -

Alcohol and Injuries Emergency Department Studies in an International Perspective

Alcohol And InjurIes Emergency Department Studies in an International Perspective Alcohol And InjurIes Emergency Department Studies in an International Perspective Editors: Cheryl J. Cherpitel, Guilherme Borges, Norman Giesbrecht, Daniel Hungerford, Margie Peden, Vladimir Poznyak, Robin Room, Tim Stockwell WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data: Alcohol and injuries: emergency department studies in an international perspective. 1.Alcohol drinking - adverse effects. 2.Alcoholic intoxication - diagnosis. 3.Wounds and injuries - etiology. 4.Emergency service, Hospital. 5.Multicenter studies. I.World Health Organization. ISBN 978 92 4 154784 0 (NLM classification: WM 274) © World Health Organization 2009 All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization can be obtained from WHO Press, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel.: +41 22 791 3264; fax: +41 22 791 4857; e-mail: [email protected]). Requests for permission to reproduce or trans- late WHO publications – whether for sale or for noncommercial distribution – should be addressed to WHO Press, at the above address (fax: +41 22 791 4806; e-mail: [email protected]). The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concern- ing the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. -

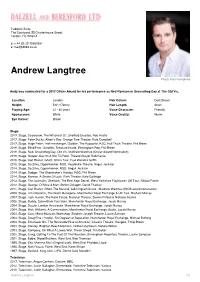

Andrew Langtree Photo: Matt Humphrey

Paddock Suite, The Courtyard, 55 Charterhouse Street, London, EC1M 6HA p: + 44 (0) 20 73360351 e: [email protected] Andrew Langtree Photo: Matt Humphrey Andy was nominated for a 2017 Olivier Award for his performance as Ned Ryerson in Groundhog Day at The Old Vic. Location: London Hair Colour: Dark Brown Height: 5'8" (172cm) Hair Length: Short Playing Age: 31 - 40 years Voice Character: Friendly Appearance: White Voice Quality: Warm Eye Colour: Brown Stage 2017, Stage, Scarecrow, The Wizard of Oz, Sheffield Crucible, Rob Hastie 2017, Stage, Peter Bucky, Albert's Boy, Orange Tree Theatre, Kate Campbell 2017, Stage, Hugh Peter / Irish messenger / Soldier, The Hypocrite, RSC, Hull Truck Theatre, Phil Breen 2016, Stage, Blind Pew / Smollett, Treasure Island, Birmingham Rep, Phil Breen 2016, Stage, Ned, Groundhog Day, Old Vic, Matthew Warchus (Olivier Award Nomination) 2016, Stage, Gooper, Cat On A Hot Tin Roof, Theatre Clwyd, Rob Hastie 2015, Stage, Carl Bruner, Ghost, China Tour, Paul Warwick Griffin 2015, Stage, Da Silva, Oppenheimer, RSC, Vaudeville Theatre, Angus Jackson 2014, Stage, Da Silva, Oppenheimer, RSC, Angus Jackson 2014, Stage, Dodger, The Shoemaker's Holiday, RSC, Phil Breen 2014, Stage, Monroe, A Stroke Of Luck, Park Theatre, Kate Golledge 2013, Stage, The Journalist, Sherlock: The Best Kept Secret, West Yorkshire Playhouse / UK Tour, Nikolai Foster 2012, Stage, George, Of Mice & Men, Bolton Octagon, David Thacker 2011, Stage, Carl Bruner, Ghost The Musical, Colin Ingram Assoc., Matthew Warchus (WOS award nomination) 2008, Stage, -

From Public Service Broadcasting to Public Service Communications

FROM PUBLIC SERVICE BROADCASTING TO PUBLIC SERVICE COMMUNICATIONS edited by Jamie Cowling and Damian Tambini 30-32 Southampton Street, London WC2E 7RA Tel: 020 7470 6100 Fax: 020 7470 6111 [email protected] www.ippr.org Registered charity 800065 The Institute for Public Policy Research (ippr), established in 1988, is Britain’s leading independent think tank on the centre left. The values that drive our work include delivering social justice, deepening democracy, increasing environmental sustainability and enhancing human rights. Through our well-researched and clearly argued policy analysis, our publications, our media events, our strong networks in government, academia and the corporate and voluntary sector, we play a vital role in maintaining the momentum of progressive thought. ippr’s aim is to bridge the political divide between the social democratic and liberal traditions, the intellectual divide between the academics and the policy makers and the cultural divide between the policy-making establishment and the citizen. As an independent institute, we have the freedom to determine our research agenda. ippr has charitable status and is funded by a mixture of corporate, charitable, trade union and individual donations. Research is ongoing, and new projects being developed, in a wide range of policy areas including sustainability, health and social care, social policy, citizenship and governance, education, economics, democracy and community, media and digital society and public private partnerships. We shall shortly open an office in Newcastle: ippr north. For further information you can contact ippr’s external affairs department on [email protected], you can view our website at www.ippr.org and you can buy our books from Central Books on 0845 458 9910 or email [email protected]. -

Maryland Citizens in Psychiatric Crisis: a Report

Maryland Citizens in Psychiatric Crisis: A Report Table of Contents B Table of Contents Acknowledgments iii Executive Summary v Introduction 1 Part 1: Emergency Department Utilization By People with Psychiatric Disabilities 7 A. Why Maryland Citizens with Psychiatric Disabilities 9 Go To Hospital Emergency Departments 1. What Would Prevent a Return Visit to the Emergency Department? 10 a. Mobile Treatment Teams/Visiting Nurses 11 b. Transportation Assistance 11 c. Crisis Beds 11 d. Crisis House 12 e. Mental Health Programs with Extended Hours 12 f. Substance Abuse Treatment 13 g. Increased Housing 13 h. Case Management/Medical Assistance 14 2. Missed Opportunities by Emergency Departments in Making Referrals To Community Resources 14 B. Secondary Utilizers and Misuse of Emergency Departments 16 C. Community Crisis Services System 17 1. Inadequate Services a. Crisis Beds 17 b. Mobile Crisis Teams 18 ii Maryland Citizens in Psychiatric Crisis: A Report [continued] Table of Contents c. Detox/Holding Beds 18 d. Urgent Care Clinics 19 e. Hotlines 19 f. Mental Health Clinics with Extended Hours/ Transportation Assistance/Mobile Treatment 19 2. Lack of Community Awareness of Crisis Services 22 3. Inappropriate Use of Crisis Beds 23 4. Inadequate Use of Crisis Beds 24 5. Restrictive Criteria for Crisis Bed Admission 25 D. Access to Community Hospital Acute Care 26 E. Barriers to Reform 28 Recommendations for System Reform 33 Part II: Te Experiences of Individuals with a Psychiatric Disability Who Use Emergency Department Services 41 A. Minimizing or Failing to Treat Medical Conditions 42 B. Informed Consent Relating to Medications and Treatment 44 C.