From Experience to Theory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Land Settlement Schemes in Nyandarua District of Kenya, with Particular Reference to Oljoro-Orok Division, 1960-1991 Martha Wangari Gikenye

Land settlement schemes in Nyandarua district of Kenya, with particular reference to Oljoro-orok division, 1960-1991 Martha Wangari Gikenye To cite this version: Martha Wangari Gikenye. Land settlement schemes in Nyandarua district of Kenya, with particular reference to Oljoro-orok division, 1960-1991. History. 1992. dumas-01312977 HAL Id: dumas-01312977 https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-01312977 Submitted on 9 May 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. LAND SETTLEMENT SCHEMES IN NYANDARUA DISTRICT OF KENYA, WITH PARTICULAR REFERENCE TO OL-JORO OROK DIVISION, 1960 - 1991. by Martha Wangari Gikenye THIS THESIS IS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN HISTORY, UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI. 1992 IFRA / ft . FRAJ6797 Lt/i4 T3460k Declaration THIS THESIS IS MY ORIGINAL WORK AND HAS NOT BEEN PRESENTED IN ANY OTHER UNIVERSITY FOR A DEGREE. 6-Mr4l~-------------- Martha Wangari Gikenye THIS THESIS HAS BEEN PRESENTED FOR EXAMINATION WITH MY APPROVAL AS UNIVERSITY SUPERVISOR. SIGNATURE Dr. David Sperling TABLE OF CONTENTS Tableof Contents ..................... I Dedication . ... .....................V Acknowledgements • Abstract ....................... Vii CRAPTERONE ....................... 1 Introduction...................... 1 1.0 Subject and area of study ............. -

Lake Turkana Archaeology: the Holocene

Lake Turkana Archaeology: The Holocene Lawrence H. Robbins, Michigan State University Abstract. Pioneering research in the Holocene archaeology of Lake Turkana con- tributed significantly to the development of broader issues in the prehistory of Africa, including the aquatic civilization model and the initial spread of domes- ticated livestock in East Africa. These topics are reviewed following retrospective discussion of the nature of pioneering fieldwork carried out in the area in the1960s. The early research at Lake Turkana uncovered the oldest pottery in East Africa as well as large numbers of bone harpoons similar to those found along the Nile Valley and elsewhere in Africa. The Lake Turkana area remains one of the major building blocks in the interpretation of the later prehistory of Africa as a whole, just as it is a key area for understanding the early phases of human evolution. Our way had at first led us up hills of volcanic origin. I can’t imagine landscape more barren, dried out and grim. At 1.22 pm the Bassonarok appeared, an enormous lake of blue water dotted with some islands. The northern shores cannot be seen. At its southern end it must be about 20 kilometers wide. As far as the eye can see are barren and volcanic shores. I give it the name of Lake Rudolf. (Teleki 1965 [1886–95]: 5 March 1888) From yesterday’s campsite we could overlook nearly the whole western and north- ern shores of the lake. The soil here is different again. I observed a lot of conglom- erates and fossils (petrification). -

10. Land Tenure Profiles In

Kenya's Water Towers Protection and Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation (WaTER) Programme LAND TENURE PROFILES IN ‘HOTSPOTS’ AND VULNERABLE AREAS ON PUBLIC AND COMMUNITY LANDS IN MT. ELGON AND CHERANGANY HILLS ECOSYSTEMS Component 4: Science to Inform Design of Community-Level Actionsand Policy Decisions Project Report August 2017 This programme is funded Kenya Forestry Research Institute By the European Union (KEFRI) Disclaimer “This document has been produced with financial assistance of the European Union. The contents of this document are the sole responsibility of the Kenya Forestry Research Institute (KEFRI), and can under no circumstance be regarded as reflecting the position of the European Union” i Cover Photo: Paddocks for livestock grazing in seasonal wetland near Cheptongei area. (Photo by Griphin Ochieng) ii Consulting Services for client Kenya Forestry Research Institute P.O Box 20412-00200 Nairobi Final Report Compiled by: Environment Management Consultants Shelter Afrique Centre, 3rd floor Wing 3A Longonot Road, Upperhill P.O.Box, 9648-00100, NAIROBI Landline: +254-020-520-6162 Cell: +254-722-579272 [email protected] iii TABLE OF CONTENT LIST OF FIGURES ................................................................................................................................. VII LIST OF TABLE .................................................................................................................................... VIII LIST OF PLATES ................................................................................................................................... -

Download List of Physical Locations of Constituency Offices

INDEPENDENT ELECTORAL AND BOUNDARIES COMMISSION PHYSICAL LOCATIONS OF CONSTITUENCY OFFICES IN KENYA County Constituency Constituency Name Office Location Most Conspicuous Landmark Estimated Distance From The Land Code Mark To Constituency Office Mombasa 001 Changamwe Changamwe At The Fire Station Changamwe Fire Station Mombasa 002 Jomvu Mkindani At The Ap Post Mkindani Ap Post Mombasa 003 Kisauni Along Dr. Felix Mandi Avenue,Behind The District H/Q Kisauni, District H/Q Bamburi Mtamboni. Mombasa 004 Nyali Links Road West Bank Villa Mamba Village Mombasa 005 Likoni Likoni School For The Blind Likoni Police Station Mombasa 006 Mvita Baluchi Complex Central Ploice Station Kwale 007 Msambweni Msambweni Youth Office Kwale 008 Lunga Lunga Opposite Lunga Lunga Matatu Stage On The Main Road To Tanzania Lunga Lunga Petrol Station Kwale 009 Matuga Opposite Kwale County Government Office Ministry Of Finance Office Kwale County Kwale 010 Kinango Kinango Town,Next To Ministry Of Lands 1st Floor,At Junction Off- Kinango Town,Next To Ministry Of Lands 1st Kinango Ndavaya Road Floor,At Junction Off-Kinango Ndavaya Road Kilifi 011 Kilifi North Next To County Commissioners Office Kilifi Bridge 500m Kilifi 012 Kilifi South Opposite Co-Operative Bank Mtwapa Police Station 1 Km Kilifi 013 Kaloleni Opposite St John Ack Church St. Johns Ack Church 100m Kilifi 014 Rabai Rabai District Hqs Kombeni Girls Sec School 500 M (0.5 Km) Kilifi 015 Ganze Ganze Commissioners Sub County Office Ganze 500m Kilifi 016 Malindi Opposite Malindi Law Court Malindi Law Court 30m Kilifi 017 Magarini Near Mwembe Resort Catholic Institute 300m Tana River 018 Garsen Garsen Behind Methodist Church Methodist Church 100m Tana River 019 Galole Hola Town Tana River 1 Km Tana River 020 Bura Bura Irrigation Scheme Bura Irrigation Scheme Lamu 021 Lamu East Faza Town Registration Of Persons Office 100 Metres Lamu 022 Lamu West Mokowe Cooperative Building Police Post 100 M. -

THE KENYA GAZETTE Published by Authorrty of the Repubhc of Kenya

SPECIAL ISSUE THE KENYA GAZETTE Published by Authorrty of the Repubhc of Kenya (Registered as a Newspaper at the G P 0 ) Vol. LXIX-No 34 NAIROBI, 4th July 1967 Price Sh 1/50 CONTENTS The National Assembly Elections (Registration of Voters) Regulations 1964 and The Local Government Elections Rules 1966-Notices to Electors 704 SUPPLEMENT No. 52 Bzlls 1967 (Published as a Special Issue on 3rd July 1967) SUPPLEMENT No 53 Acts 1967 SUPPLEMENT No 54 Acts 1967 ' 704 TH F, K EN YA G AZET TE 4th July 1967 GAZETTE N OTTCE N O 2420 - --- Regtstratton Umt No Place of Regkstratton TH E N ATION AL ASSEM BLY ELECTION S (REGISTRATION OF VOTERS) REGULATION S 1964 (L N 56 of 1964) NYBRI DISTRICT Kam u 364 Oë ce of the Dlstrlct Oflicer, THE LOCAL GOVERN M EN T ELECTION S RU LES 1966 M athlra (L N 101 o! 1966) Gatundu 365 ,, N Chehe (lncludlng Cheho 366 ,, olqcs To El-Bc'roits Forest Statlon) NOTICE ls heleby gwen that lt ls proposed to com plle new KaD yu 367 , reglsters of electors for the purpose of the electlon of m em bers GR atgealt l 3698 ,, to- G athelm 370 ,, ,, (aj the Natlonal Assembly, Oalkuyu CTA'' 371 > (b) Local Authontles G aclklwuyku $$B'' 3732 ,' , A1l persons who wlsh to be reglstered as electols for the Barlcho 374 ,, purpose of elther or both of these electlons, and who are lcuga 375 ,, qualé ed to be so reglstered Gakuyu 376 ,, , m ust attend personally before the K R eglstratlon Om cer or A sslstant Reglstratlon OK cer for the M abroaltglnoaln Tl ownshlp a3,7J98 ,, reglstratlon um t ln whlch they are qualé ed to be reglstered, Tjuu -

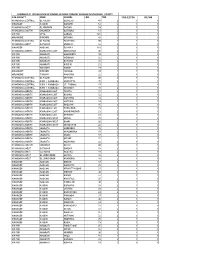

Nyandarua County

SUMMARY OF INSTALLATION OF DEVICES IN PUBLIC PRIMARY SCHOOLS IN NYADARUA COUNTY SUB-COUNTY ZONE SCHOOL LDD TDD PROJECTOR DCSWR NYANDARUA CENTRAL OL-KALOU OLKALAU 43 2 1 1 KINANGOP NJABINI KARIAHU 53 2 1 1 NYANDARUA WEST OLJOROROK GATIMU 74 2 1 1 NYANDARUA SOUTH ENGINEER GATHARA 69 2 1 1 KIPIPIRI GETA MARIMU 101 2 1 1 MIRANGINE DUNDORI GITHIMA 43 2 1 1 NYANDARUA CENTRAL OL KALOU PASSENGA 90 2 1 1 NYANDARUA WEST GATHANJI MWENJA 62 2 1 1 KINANGOP MAGUMU GITHINJI 187 2 1 1 NYANDARUA NORTH NDARAGWA EAST NDARAGWA 45 2 1 1 KIPIPIRI MIHARATI MACHINERY 10 2 1 1 KIPIPIRI MIHARATI WENDANI 12 2 1 1 KIPIPIRI MIHARATI RUTUMO 18 2 1 1 KIPIPIRI MIHARATI KIPIPIRI 21 2 1 1 KIPIPIRI WANJOHI KIMBO 14 2 1 1 MIRANGINE DUNDORI SABUGO 20 2 1 1 MIRANGINE TUMAINI WANJURA 22 2 1 1 NYANDARUA CENTRAL OL KALOU MUNYEKI 20 2 1 1 NYANDARUA CENTRAL RURII / KAIMBAGA MANYATTA 15 2 1 1 NYANDARUA CENTRAL RURII / KAIMBAGA ST. THOMAS 17 2 1 1 NYANDARUA CENTRAL RURII / KAIMBAGA MUKINDU 19 2 1 1 NYANDARUA NORTH NDARAGWA EAST THUITA 11 2 1 1 NYANDARUA NORTH NDARAGWA EAST KIHARO 12 2 1 1 NYANDARUA NORTH NDARAGWA EAST KAHUTHA 13 2 1 1 NYANDARUA NORTH NDARAGWA EAST MATUIKU 14 2 1 1 NYANDARUA NORTH NDARAGWA EAST IHIGA-INI 15 2 1 1 NYANDARUA NORTH NDARAGWA EAST NYONJORO 19 2 1 1 NYANDARUA NORTH NDARAGWA EAST KIANDONGORO 21 2 1 1 NYANDARUA NORTH NDARAGWA EAST MURICHU 21 2 1 1 NYANDARUA NORTH NDARAGWA WEST NDIVAI 15 2 1 1 NYANDARUA NORTH NDARAGWA WEST BAARI 20 2 1 1 NYANDARUA NORTH NDARAGWA WEST MUNG'ETHO 22 2 1 1 NYANDARUA NORTH SHAMATA MAKEREKA 15 2 1 1 NYANDARUA NORTH SHAMATA MUKAMBURA -

Nyandarua, Kenya

Joint Work Programme for Equitable Economic Growth in Cities Figure 1: Campaign Cities map Nyandarua Nairobi Kajiado Campaign City Brief Nyandarua, Kenya Population1 Number of cities with People living below % of residents engaged over 100,000 inhabitants poverty line in agriculture sector 600,000 4 43% 50% A recognition of the importance of equitable In Nyandarua, Kenya, the Campaign Cities Initiative economic growth (EEG), and the need to understand was implemented from December 2018 to April how EEG can be effectively promoted in secondary 2020 by the UN-Habitat. The initiative assisted the cities, led to the establishment of Cities Alliance’s Joint counties of Nyandarua and Kajiado (see Figure 1) Work Programme (JWP) on EEG in cities. prepare evidence-based policy recommendations concerning how municipal public goods and A trademark component of the JWP-EEG programme services could be delivered in a manner that directly has been the Campaign Cities Initiative (2016–2020). contributes to EEG. In Nyandarua, the focus was land This initiative began by creating local partnerships in use control to managing urban development and the eight secondary cities in Bangladesh, Uganda, Ghana, preparation of a strategy for the development of a and Kenya. For each city, a diagnostic assessment wholesale market and a logistics centre. of constraints to EEG was produced, resulting in the selection of a particular public good or service in the city that should be prioritised. Nyandarua context Approach and methodology Nyandarua County lies in the centre of Kenya close to Each Campaign City initiative took around 24 months Nairobi to which it is linked by major truck roads. -

Interim Independent Boundaries Review Commission (IIBRC)

REPUBLIC OF KENYA The Report of the Interim Independent Boundaries Review Commission (IIBRC) Delimitation of Constituencies and Recommendations on Local Authority Electoral Units and Administrative Boundaries for Districts and Other Units Presented to: His Excellency Hon. Mwai Kibaki, C.G.H., M.P. President and Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces of the Republic of Kenya The Rt. Hon. Raila Amolo Odinga, E.G.H., M.P. Prime Minister of the Republic of Kenya The Hon. Kenneth Marende, E.G.H., M.P. Speaker of the National Assembly 27th November, 2010 Table of Contents Table of Contents ........................................................................................................................................... i Letter of Submission .................................................................................................................................... iv Acronyms and Abbreviations ..................................................................................................................... vii Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................... viii 1.0 Chapter One: Introduction ................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Aftermath of the General Elections of 2007 ..................................................................................... 1 1.1.1 Statement of Principles on Long-term Issues and Solutions ........................................................ -

Olkalou Sub-County

#GOVKIMEMIADELIVERS Ol’Kalou editionJuly 1 st , 2020 - June 30 th , 2021 NYANDARUA COUNTY Special Development Updates Ol’Kalou edition July 1st, 2020 - June 30th, 2021 SN. 018/001 #GOVKIMEMIADELIVERS a journey of hope www.nyandarua.go.ke Nyandarua County Government NyandaruaCG018i #GOVKIMEMIADELIVERS Ol’Kalou editionJuly 1 st , 2020 - June 30 th , 2021 NYANDARUA COUNTY MAP 0441 ENGINEER 0442 GATHARA 0443 NORTH KINANGOP 0444 MURUNGARU 0445 NJABINI / KIBURU 0446 NYAKIO 0447 GITHABAI 0448 MAGUMU 0449 WANJOHI 0450 KIPIPIRI 0451 GETA 0452 GITHIORO 0453 KARAU 0454 KANJUIRI RANGE 0455 MIRANGINE 0456 KAIMBAGA SUB-COUNTIES 0457 RURII 0458 GATHANJI 0459 GATIMU 0460 WERU 0461 CHARAGITA 0462 LESHAU PONDO 0463 KIRIITA 0464 CENTRAL 0465 SHAMATA ii #GOVKIMEMIADELIVERS Ol’Kalou editionJuly 1 st , 2020 - June 30 th , 2021 EDITORIAL TEAM Team Leader: Hon. Dominic Murani Editorial Director: Mary Ndorongo Editors: Jesse Masai; Mbugua Muchoki Contributors: Esther Muthoni; Martin Ngugi; Evans Njoroge; Irene Kiragu; Sylvia Nyambura; Loise Njeri, Patriciah Wanjiku; Nehemiah Maina; Deborah Ongeri; John Njuguna; Beatrice Mugane; Phillip Githaiga; Dorcas Njeri; Ivy Wanjiru; John Wanyeki Design & Layout: Edgar Kamau; Allan Mbugua; Julius Muriuki Photography: Governor’s Press Service; Directorate of Communication and Public Relations Copyright, 2021 – Published by Department of Public Administration and Information Communication Technology at the Nyandarua County Government Headquarters in Ol’Kalou Printed by Hills Converters (K) Limited www.hillsconverters.co.ke Off Mombasa Road, +254 719 411 334 / 0780 411 334 Along Syokimau Katani Road – Next to Sava Builders P.O Box 2990 - 00200 Nairobi, Kenya iii #GOVKIMEMIADELIVERS Ol’Kalou editionJuly 1 st , 2020 - June 30 th , 2021 About Nyandarua County Government he mission of Nyandarua County Government is to provide an enabling social, eco- Tnomic and political environment for the holistic transformation of all its citizens. -

The 'Kenya Gazette

a ** w # .. p e * œ ' ' < ) f h @ ;W u s ox *o TH E 'K EN Y A G A ZETTE ' Pablished pader the Authority of His Excellency the Governor of the Colony and Pm tectbrate @1 KG. y*, . (Registereb as a Ntwspalxr at tlw G.P.O.) . ' . J . C 11::::2:1 1 ZL ' . ZL'JZJJ 2 E J 7 ' ' 2E2 - LJZZFZE 'iE 2 ' ' ' Vo'I. LXII= N o. 5 N A. TROBI, 19th January, 1960 Price : Sh. t :2:1::::::: . , . ZZZZZZ 2 ' ' ; 7X ï ZZX-Z 22.222f2--2- us c c coNTENTs GAZETTE NOTICES GAZETTE NoncBs--lcoa/d.) PAGE PAGF Appoiptmenl, ctc. 'Eldorvt . Municipal Coundi-Election Result 56 The Transfer and Delegation of Powers Ordinance- The Production of Food Crop s Rules--Earliest and latest . Temporary Transfer of Powere .' . 46 datcxs of planting . ' ' 56 ' ' n e Kcnya fcoristitution) Order in Council- Transport Liccnsing . 57-5j DecIaration of Iqoapacity of M inister 46 n e . Credit . to Africans (Control) Ordinance-r ertiicate ' Appointment of Temporary M inister . 46 of Exem' ption . 60-62 Appoin.tment of Mem'ber of Councll of State . 47 Tenders , . 62 Revocation of Appointment of Temporary M ember . 47 Appointment of Nominated Member . ' 47 The W eights and M eàsures Ofdinance- Notice 'to Traders 63 . Acting Governor- Assumption of Oëce . 41 Ciyil Aircraft Acciddnt- lnspector's Invçstigation 63 n e Immigration Ordinance-Appol.ntment 47 lmss of Tax Reserve Certiscates 60 The Education Ordinance-Resignation 47 Farral Inc.- Appointmept . - . 63 . The Hospital Treatment Relief (European) Ordinance- The Societies Ordlnance-cancellation of Reglstration . 63 Approved Hospitals . -

Non-Technical Summary DRAFT

REPORT Non-Technical Summary DRAFT Submitted to: Submitted by: Golder Associates (UK) Ltd Cavendish House, Bourne End Business Park, Cores End Road, Bourne End, Buckinghamshire, SL8 5AS, UK +44 0 1628 851851 1433956.637.A1 June 2020 June 2020 1433956.637.A1 Table of Contents 1.0 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................................... 1 2.0 POLICY, LEGAL AND ADMINISTRATIVE FRAMEWORK ....................................................................... 2 3.0 IMPACT ASSESSMENT METHODOLOGY ............................................................................................... 2 4.0 STAKEHOLDER ENGAGEMENT .............................................................................................................. 3 5.0 PROJECT DESCRIPTION .......................................................................................................................... 3 6.0 BASELINE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................... 6 6.1 Geology, Geohazards and Seismicity ............................................................................................... 6 6.2 Soils ................................................................................................................................................... 6 6.3 Weather and Climate ....................................................................................................................... -

Water Resource Conflict in Kenya: the Case of Turkwel Dam and Pokot-Turkana Relations, 1984-2015

Faculty of Arts, Department of History MA Project Water Resource Conflict in Kenya: The Case of Turkwel Dam and Pokot-Turkana Relations, 1984-2015 By Andreas Nandelenga Submitted in partial fulfilment of Master of Arts in Armed Conflict and Peace Studies University of Nairobi 2019 DECLARATION This is my original work and has not been submitted for an award of a degree either in any University or any other institution. Signed _____________________________ Date ________________________ Andreas Nandelenga C50/78008/2015 This project has been submitted for an examination with our approval as University supervisors. Dr. KENNETH S. OMBONGI Signature:…………………….. Date:…………………………. Dr. MARGARET GACHIHI Signature:…………………….. Date:…………………………. ii DEDICATION To my beloved mother Julia Mukoya Nandelenga, late father Timothy Nandelenga and late brother Joseph Nandelenga. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like to express my thanks, first and foremost, to the almighty God for walking me through this work. Secondly, I would like to thank the University of Nairobi, through the Department of History and Archaeology for granting me an opportunity to take my studies. Special thanks to my two supervisors Dr. Kenneth S. Ombongi and Dr. Margaret Gachihi without whom this project could not have been completed. They constantly mentored; panel beat, corrected and encouraged me through this academic process. I cannot forget to thank all the academic staff members of the Department of History who made my studies possible. I wish to particularly thank Dr. George Gona, Dr. Ben Nyanchoga, Dr. Misigo, Prof Vincent Simiyu and other members of academic and non-academic staff for their kind assistance. My gratitude to Dr. Solomon Owoche, Dr.