Death to Deification: Reading the Many Tales of Goddess Tusu

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Delhi Sultanate Pdf Download Delhi Sultanate Notes PDF Download |

delhi sultanate pdf download Delhi Sultanate Notes PDF Download | Delhi Sultanate Notes PDF Download - Delhi Sultanate Chapterwise and Typewise Notes Delhi Sultanate Delhi Sultanate notes PDF in Hindi Delhi Sultanate Book PDF, Delhi Sultanate handwritten Notes PDF Delhi Sultanate Chapterwise and Typewise Solved Paper class notes PDF Delhi Sultanate Notes Book PDF Delhi Sultanate – Download Social Studies Notes Free PDF For REET /UTET Exam. Social Studies is an important section for REET, MPTET , State TET, and other teaching exams as well. Social studies is the main subject in the REET, exam Paper II. In REET, UTET Exam, the Social Studies section comprises a total 60 questions of 60 marks, in which 40 questions come from the content section i.e. History, Geography and Political Science and the rest 20 questions from Social Studies Pedagogy section. At least 10-15 questions are asked from the History section in the REET, UTET Social studies section. Here we are providing important notes related to the Delhi Sultanate. Delhi Sultanate. The period from 1206 to 1526 in India history is known as Sultanate period. Slave Dynasty. In 1206 Qutubuddin Aibak made India free of Ghazni’s control. Rulers who ruled over India and conquered new territories during the period 1206-1290 AD. are known as belonging to Slave dynasty. Qutubuddin Aibak. He came from the region of Turkistan and he was a slave of Mohammad Ghori. He ruled as a Sultan from 1206 to 1210. While playing Polo, he fell from the horse and died in 1210. Aram Shah. After Aibak’s death, his son Aram Shah was enthroned at Lahore. -

Volume 16, Issue 1, June 2018

Volume 16, Issue 1, June 2018 Contradictory Perspectives on Freedom and Restriction of Expression in the context of Padmaavat: A Case Study Ms. Ankita Uniyal, Dr. Rajesh Kumar Significance of Media in Strengthening Democracy: An Analytical Study Dr. Harsh Dobhal, Mukesh Chandra Devrari “A Study of Reach, Form and Limitations of Alternative Media Initiatives Practised Through Web Portals” Ms. Geetika Vashishata Employer Branding: A Talent Retention Strategy Using Social Media Dr. Minisha Gupta, Dr. Usha Lenka Online Information Privacy Issues and Implications: A Critical Analysis Ms. Varsha Sisodia, Prof. (Dr.) Vir Bala Aggarwal, Dr. Sushil Rai Online Journalism: A New Paradigm and Challenges Dr. Sushil Rai Pragyaan: Journal of Mass Communication Volume 16, Issue 1, June 2018 Patron Dr. Rajendra Kumar Pandey Vice Chancellor IMS Unison University, Dehradun Editor Dr. Sushil Kumar Rai HOD, School of Mass Communication IMS Unison University, Dehradun Associate Editor Mr. Deepak Uniyal Faculty, School of Mass Communication IMS Unison University, Dehradun Editorial Advisory Board Prof. Subhash Dhuliya Former Vice Chancellor Uttarakhand Open University Haldwani, Uttarakhand Prof. Devesh Kishore Professor Emeritus Journalism & Communication Research Makhanlal Chaturvedi Rashtriya Patrakarita Evam Sanchar Vishwavidyalaya Noida Campus, Noida- 201301 Dr. Anil Kumar Upadhyay Professor & HOD Dept. of Jouranalism & Mass Communication MGK Vidhyapith University, Varanasi Dr. Sanjeev Bhanwat Professor & HOD Centre for Mass Communication University of Rajasthan, Jaipur Copyright @ 2015 IMS Unison University, Dehradun. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in any retrieval system of any nature without prior written permission. Application for permission for other use of copyright material including permission to reproduce extracts in other published works shall be made to the publisher. -

Chittorgarh (Chittaurgarh) Travel Guide

Chittorgarh Travel Guide - http://www.ixigo.com/travel-guide/chittorgarh page 1 Cold weather. Carry Heavy woollen, umbrella. When To Max: Min: Rain: 111.0mm Chittorgarh 22.89999961 18.29999923 8530273°C 7060547°C Perched atop a wide hill, the Aug sprawling fort of Chittorgarh is a VISIT Cold weather. Carry Heavy woollen, testimony to the grandeur of umbrella. http://www.ixigo.com/weather-in-chittorgarh-lp-1143785 Max: Min: 18.0°C Rain: 210.0mm Indian architecture. Built over 17.89999961 centuries by various rulers and 8530273°C Jan known far and wide for the beauty Cold weather. Carry Heavy woollen. Sep of Queen Padmini, this fort was Famous For : City Max: Min: Rain: 0.0mm Cold weather. Carry Heavy woollen. 20.70000076 9.399999618 Max: 23.5°C Min: Rain: 21.0mm ravaged by Allahudin Khilji and his 2939453°C 530273°C 16.10000038 armies and now stands in ruins. Once a prosperous ancient city that was 1469727°C Feb ravaged due to the fables circulating about Drive through the fort and Cold weather. Carry Heavy woollen. Oct experience the lost grandeur of Rani Padmini's beauty, Chittorgarh is a Max: Min: Rain: 21.0mm Pleasant weather. Carry Light woollen. centre of inspiring and almost mythical 23.79999923 7.900000095 Max: Min: Rain: 0.0mm erstwhile emperors and the beauty 7060547°C 367432°C 30.10000038 21.29999923 stories. The residence of the erstwhile of the dry landscapes of Rajasthan. 1469727°C 7060547°C Rajput warriors, this fort is now largely in Mar Nov ruins. The sites of historical interest include Cold weather. -

Identity Politics and Hindu Nationalism in Bajirao Mastani and Padmaavat Baijayanti Roy Goethe University, Frankfurt Am Main, [email protected]

Journal of Religion & Film Volume 22 Issue 3 Special Issue: 2018 International Conference Article 9 on Religion and Film, Toronto 12-14-2018 Visual Grandeur, Imagined Glory: Identity Politics and Hindu Nationalism in Bajirao Mastani and Padmaavat Baijayanti Roy Goethe University, Frankfurt am Main, [email protected] Recommended Citation Roy, Baijayanti (2018) "Visual Grandeur, Imagined Glory: Identity Politics and Hindu Nationalism in Bajirao Mastani and Padmaavat," Journal of Religion & Film: Vol. 22 : Iss. 3 , Article 9. Available at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol22/iss3/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Religion & Film by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Visual Grandeur, Imagined Glory: Identity Politics and Hindu Nationalism in Bajirao Mastani and Padmaavat Abstract This paper examines the tropes through which the Hindi (Bollywood) historical films Bajirao Mastani (2015) and Padmaavat (2018) create idealised pasts on screen that speak to Hindu nationalist politics of present-day India. Bajirao Mastani is based on a popular tale of love, between Bajirao I (1700-1740), a powerful Brahmin general, and Mastani, daughter of a Hindu king and his Iranian mistress. The er lationship was socially disapproved because of Mastani`s mixed parentage. The film distorts India`s pluralistic heritage by idealising Bajirao as an embodiment of Hindu nationalism and portraying Islam as inimical to Hinduism. Padmaavat is a film about a legendary (Hindu) Rajput queen coveted by the Muslim emperor Alauddin Khilji (ruled from 1296-1316). -

Mothering the Mother Feminism And

Issue 1 Vol. 3, May 2016 Crimes Against Hinduism in India’s North East 17 Raids and Still Standing Akbar the Great: Ruins of Somnath Temple in The Lies of Bollywood 19th Century Gujarat Mothering the Mother The Divine Feminine Consciousness! Feminism and the Two Matriarchs of the Mahabharata 1 HINDUISM NOW Hindu Calendar—May 2016 03rd May : Varuthini Ekadashi, Vallabhacharya Jayanti 04th May: Pradosh Vratam, Agni Nakshatram Begins 05th May: Masik Shivaratri 06th May: Vaishakha Amavasya, Darsha Amavasya 07th May: Chandra Darshan, Masik Karthigai, Rabindranath Tagore Jayanti 08th May: Parashurama Jayanti, Tagore Jayanti *Bengal region, Rohini Vrat 09th May: Akshaya Tritiya, Varshitap Parana, Matangi Jayanti 10th May: Vinayaka Chaturthi, Ramanuja Jayanti 11th May: Shankaracharya Jayanti, Surdas Jayanti, Skanda Sashti 12th May: Ganga Saptami 14th May: Masik Durgashtami, Bagalamukhi Jayanti, Vrishabha Sankranti 15th May: Sita Navami 16th May: Mahavir Swami Kevalgyan 17th May: Mohini Ekadashi 18th May: Parashurama Dwadashi 19th May: Pradosh Vrat 20th May: Narasimha Jayanti, Chhinnamasta Jayanti 21st May: Vaishakha Purnima, Kurma Jayanti, Buddha Purnima, Purnima Upavas, Vaikasi Visakam 22nd May: Jyeshtha Begins, Narada Jayanti 25th May: Sankashti Chaturthi 28th May: Agni Nakshatram Ends 29th May: Bhanu Saptami, Kalashtami 31st May: Hanuman Jayanti *Telugua 2 HINDUISM NOW Issue 1 - Volume 3 - May 2016 Contents Owned, Created, Designed by: Nithyananda University Press Published by: Message from the Avatar ................................................. 4 Nithyananda Peetham, Bengaluru Adheenam Kallugopahalli, Off Mysore Road, Bidadi Hinduism Around the World .........................................8-9 Ramanagaram - 562109 Phone: +91 80 2727 9999 Main Feature - Crimes Against Hinduism Website: www.hinduismnow.org Atrocities of the Delhi Sultanate ............................... 10-13 Editorial Board The Lust of Allaudin Khilji .. -

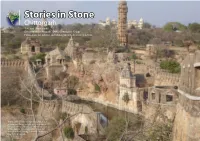

Stories in Stone Chittorgarh Text and Photographs: Discover India Program (DIP), Chittorgarh Group Foundation for Liberal and Management Education (FLAME)

Stories in Stone Chittorgarh Text and photographs: Discover India Program (DIP), Chittorgarh Group Foundation for Liberal and Management Education (FLAME) Here’s where history has left its footprints deep in stone and the air is light with the breath of romance, beauty and chivalry. Within the walls of this gigantic fort, drama after drama has been played out, leaving behind the lingering fragments of legends. 38 Heritage India August 2010 - October 2010 Volume 3 Issue 3 Heritage India August 2010 - October 2010 Volume 3 Issue 3 39 History says that the Chittor fort in southern consolidated his forces and established Mewar, making Vijay Stambha (Victory tower) Rajasthan was built by Bappa Rawal in the 8th century Chittorgarh the kingdom’s first capital. From the 8th to CE and it served as the capital of Mewar until it was the 16th century CE, Bappa Rawal’s descendants ruled invaded by Akbar. Its imperial presence was enhanced over Mewar from Chittorgarh. The fort has witnessed by the fact that it sat atop a 180 m high hill, imposing the illustrious rule of kings like Rana Kumbha and Rana and impregnable. However, its numerous elements Sanga. were not just put in place at the start but instead built over the centuries of its occupation. It was equipped The first defeat befell Chittorgarh in 1303 when with defence and civic buildings that were protected Ala-ud-din Khilji, the Sultan of Delhi, besieged the fort, by endless walls with recurring bastions. Sprawling to capture the beautiful Rani Padmini, wife of Rana over 289 hectares, Chittorgarh was a centre of trade, Ratan Singh. -

Friction Between Cultural Representation and Visual Representation with Reference to Padmaavat

postScriptum: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Literary Studies 1 postScriptum: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Literary Studies ISSN: 2456-7507 <postscriptum.co.in> Online – Open Access – Peer Reviewed – DOAJ Indexed Volume V Number i (January 2020) Friction between Cultural Representation and Visual Representation with Reference to Padmaavat Mita Bandyopadhyay Research Scholar, Dept. of Humanities and Social Sciences, National Institute of Technology, Durgapur & Arindam Modak Associate Professor, Dept. of Humanities and Social Sciences, National Institute of Technology, Durgapur Abstract According to the Cultural theorist, Stuart Hall, images of objects do not have meaning in themselves. Meaning is generated according to the contextual fixation between the user and the representational significance of that object. The representative meaning of the object when shared by a group of people becomes a cultural practice. It has been observed that when the same cultural practice is represented further in the visual media, in the form of cinema, a conflict arises between the cultural representation of the image and its visual representation. Padmaavat (2018), a film directed by Sanjay Leela Bhansali, went through several oppositions by the different classes of the society across the country, owing to the portrayal of different characters and the social background of the movie. The social discontent created by people revolved around a number of issues: the main issue being a different representation of Rani Padmavati and Allauddin Khilji in the movie, in contrast to the way they are represented and accepted in the popular culture. By using Stuart Hall’s conceptual idea of ‘representation’ in cultural practices, an attempt has been taken to show how a friction is created when an ideology formed through the cultural representation is again represented through the visual media. -

Download File

Chapter 5 FUTURE’S PAST Manan Ahmed Asif Introduction Prophets are best at predicting the future – though, they tend towards the dystopic and the apocalyptic. The more philosophically inclined among us, when asked to imagine the future, create utopias secluded in the woods or contained on an island – in other words, by clearing away the accretions of the past and the unseemly present. Everyone else tends to read the best or the worst of the present moment and write it into the future – cars replaced by flying cars, cities replaced by mega cities, wars replaced by greater wars and so on. Such is the grasp that the present has on us – it is always natural, progressive, rational and just so. Historians, being neither prophets nor philosophers, usually have no thoughts on the future. We are busy figuring out what happened, why it did not happen some other way and why we should care it happened the way it did. But we do have a charge to unsettle whatever “truths” seem above reproach in our presents, to question basic assumptions of how things appear now and to argue for an imagination that ponders all possible futures, not just the ones that seem predestined. My claim, as a historian, is simple: The “South Asia” we inhabit is a recent construct. It is a limited and restrictive political space as compared to more than a thousand years of textual history and thousands more in material and cultural memory. The stories it currently tells are themselves limited, the imaginations it cultivates are themselves rigid. -

Rajputs - Sailent Features

Rajputs - Sailent Features Study Materials THE RAJPUTS (AD 650-1200) Chandeta kingdom was founded by Yashovarma of Chandel in the region of Bhajeka Bhutika (later came After Harshavardhana. the Rajputs emerged as a to beknown as Bundelkhan). Their capital was powerful force in western and central India and Mahoba. Their Prominent kings were Dhanga and dominated the Indian political scene fo nearly 500 Kirthiverma. The last ruler from the dynasty merged years from the seventh century. They emerged from with Prithviraj Chauhan in AD 1182. the political chaos that surfaced after the death of Kirthiverma the Chandela ruler defeated the Harshavardhana. Out of the political disarray prevalent Chedi ruler in the eleventh century. Later, in North India, the Rajputs chalked out the small Lakshamanaraja emerged as a powerful Chedi Rajput kingdoms of Gujarat and Malwa. From the eighth to ruler. His kingdom was located between the Godavari twelfth century they struggled to keep themselves and the Narmada and his capital was Tripura (near independent. But as they grew bigger the infighting Jabalpur). made them brittle, theyfell prey to the rising Like Kanauj, Malwa was the symbol of the domination of the Muslim invaders. Among them the Rajputana power. Krishnaraja (also called King Gujara of Pratihara, the Gahadwals of Kanauj, the Upendra) founded this kingdom. Their capital was Kalachuris of Chedi, the Chauhans of Ajmer, the Dhar (Madhya Pradesh). The prominent kings from Solankis of Gujarat and the Guhtlotas of Mewar are this dynasty were Vakpatiraju- Munjana II. Bhoja I, important. Bhoja II. In Malwa, the Parmars ruled and the most The first Gujara-Pratihara ruler was famous of them was King Bhoja. -

Ideological History, Contested Culture, and the Politics of Representation in Amar Chitra Katha

Nilakshi Goswami Boston University Ideological History, Contested Culture, and the Politics of Representation in Amar Chitra Katha Abstract The evolution of culture and societies through the course of history is not a priori but is discursively constructed by a constellation of beliefs and myths and is shaped by different ideological institutions. This paper addresses the historical narratives of Amar Chitra Katha (from now on ACK), the first indigenous children’s comics in India, which began publishing in 1967. Despite a growing body of research on the media landscape in postcolonial India, Indian children’s media culture continues to be underrepresented in the field of history and popular culture. When we engage with the world of comics and graphic novels, we realize how it shapes, and is shaped by, not just the minds of individuals but also the collective consciousness of communities and their (un)sung histories. ACK has been an important cultural institution that has played a significant role in defining, for several generations of Indian readers, what it means to be Hindu and Indian. In the process, the comics tradition seems to portray a delimited world view of India, often erasing non-Hindu subjects and lower caste strata of the society from India’s history. While the research will focus on reformist and revisionist impulses that ACK carries, it will also engage in the way these historical parables of India are narrated, the stories that are chosen to be told, the faces and the voices that are prioritized (or obliterated) for the purpose, and the collaboration of literary and visual image on which they rely to accomplish their re-presentation of history. -

Disguising Cowardice As Honour: the Many Padmavats

Disguising Cowardice as Honour: The Many Padmavats SWAPNA SUNDAR 28 FEB 2018 17:08 IST People shouts slogans to demand ban on Bollywood movie Padmavat near the Central Board of Film Certification center in Mumbai, India, Friday, Jan. 12, 2018. (AP Photo/Rajanish Kakade) - AP The film 'Padmavat' glorifies mass suicide by Rajput women as a mode of voluntary death that confers honour on the community. Historical precedents of mass suicide provide evidence that mass suicide in the face of certain military defeat, is the result of careful preparation and coercion. Is the mass suicide committed by Rajput women in the film Padmavat a voluntary and honourable act, or did they succumb to military coercion and propaganda? Swapna Sundar, Public Policy Scholar, The Hindu Centre for Politics and Public Policy, takes a step back from the rabble of protests to throw the spotlight on the patriarchal and militarist thought processes throughout history that reframe defeat as honour and deprive women of their agency over life. hree interesting ideas arise when recalling the furore that erupted around the release of the film Padmavat 1. The first is that of mass suicide when T the fighting forces perceive or encounter imminent defeat; the second, the deprivation of agency in the victims of mass suicides; and third, the valorisation of the mass suicide events to camouflage the lack of resistance on the part of, and humiliating defeat of the fighting force. Rajputs have certainly not been the first or the only people in the world to commit mass suicide when faced with an overwhelming enemy force, nor is Rajasthan the only site in the world of repeated mass suicides; and yet these horrific occurrences – the consequence of poor military strategy, cowardice and propaganda – have been propagated and revered as heroic instances that speak to the courage and honour of the community. -

Padmaavathdfullmoviedownload

PadmaavatHDFullMovieDownload PadmaavatHDFullMovieDownload 1 / 4 2 / 4 youtube, youtube to mp3, download youtube, mymp3song, hindi music lyrics ,download ... Deepika Padukone \u0026 Ranveer Singh Latest Hindi Full Movie | Shahid ... Padmavat full movie 2017 | bollywood movie promotional event| ranveer .... Padmavati in Hindi 2018 HINDI FULL MOVIE ONLINE DOWNLOAD from MovieHAhd.com. Presenting the Official Trailer of Padmaavat starring Deepika .... Padmaavat Telugu Full Movie Watch Online Free Download (2018) Jan 30, 2018 · padmavati 2018 hindi full movie download Padmaavat (formerly ... Listen to Padmaavat Hindi Full Movie 1080p Hd Mp4 Movie Download and 158 more episodes by K93n Na1 Kansai Chiharu.rar, free! No signup or install .... BollyFlix · Download London Fields (2018) Dual Audio {Hindi-English} Movie 480p | 720p | 1080p BluRay 400MB | 1GB · Download Suicide Squad (2016) English { .... Padmavat full movie download in 3d. CastDeepika Padukone, Ranveer Singh. Shahid Kapoor. ProducerSanjay Leela Bhansali, Ajit Andhare.. Jan 14, 2018 - Download Bollywood ,hollywood ,south dubbed, dual audio ,bangla, hevc/h265 Movies in all quality and size via high speed single resumable .... You Searched For "padmaavat full movie download". No Data Found. वायरल · View All · भीषण गर्मी के बावजूद कोरोना के कहर ... Beatmania Iidx 15 Dj Troopers Or download free padmaavat 2018 hindi 480p bluray.mkv. ... telegram. » Latest HD Hindi Movies Download @Filmyzilla. Padmaavat 2018 Hindi 480p Bluray.mkv .... If you watch Padmaavat full Movie ,then you can use our app .You can watch and download easily your movies from this app. There you can ... wp ultimate csv importer pro nulled 17 FULL Complete IDS SDD Land Rover Jaguar v138.02 Mit Erfolg Zu Telc Deutsch B2 Pdf Download Padmaavat | Full Movie songs and screenshot | Hindi | Ranveer Singh | Shahid ..