School of Darkness by Bella Dodd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The History Books Tell It? Collective Bargaining in Higher Education in the 1940S

Journal of Collective Bargaining in the Academy Volume 9 Creating Solutions in Challenging Times Article 3 December 2017 The iH story Books Tell It? Collective Bargaining in Higher Education in the 1940s William A. Herbert Hunter College, City University of New York, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://thekeep.eiu.edu/jcba Part of the Collective Bargaining Commons, Higher Education Commons, Labor and Employment Law Commons, Labor History Commons, Legal Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Herbert, William A. (2017) "The iH story Books Tell It? Collective Bargaining in Higher Education in the 1940s," Journal of Collective Bargaining in the Academy: Vol. 9 , Article 3. Available at: http://thekeep.eiu.edu/jcba/vol9/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Collective Bargaining in the Academy by an authorized editor of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The iH story Books Tell It? Collective Bargaining in Higher Education in the 1940s Cover Page Footnote The er search for this article was funded, in part, by a grant from the Professional Staff onC gress-City University of New York Research Award Program. Mr. Herbert wishes to express his appreciation to Tim Cain for directing him to archival material at Howard University, and to Hunter College Roosevelt Scholar Allison Stillerman for her assistance with the article. He would also like to thank the staff ta the following institutions for their prompt and professional assistance: New York State Library and Archives; Tamiment Library and Robert F. -

Attack on Public Workers Forum Worthy

NOTE WORTHY Work History News Save the date! L H A Miriam Frank Book Talk: Out in the Union: A Labor History of Queer America New York Labor History Association, Inc. September 17, 6:00 p.m. Tamiment Library NYU A Bridge Between Past and Present Volume 31 No 2 Summer | Fall 2014 A joint event sponsored by Tamiment and the New York Labor History Association Attack on public workers forum By Joseph Lopez movement. Unions marched side-by-side PEOPle’s ClimaTE MARCH rganized labor is the enemy—or with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in the 1960s and were an essential partner in the so right-wing media outlets like battle for racial and economic equality. New York City Fox News and politicians like O Garrido mentioned the 2012 Chicago Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker tell Teacher’s strike, which succeeded because Sunday, September 21 us. Private sector workers are inundated the union reached out to parents and made with misinformation about unions being issues such as teacher evaluations based on greedy and self-serving institutions that THIS IS AN INVITATION TO CHANGE EVERytHING. student performance a public concern. cause cities to fall into financial ruin, like “Private sector workers buy into the lies In September, world leaders are coming to New York City for a UN summit on Lopez Joseph Detroit’s recent bankruptcy. How do we because they don’t have the benefits we do,” the climate crisis. UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon is urging government change this image of public employee Emil Pietromonaco, UFT, and Henry said Emil Pietromonaco, secretary of the Garrido, DC 37 at May 8th conference. -

The Fight for Democratic Education in Post-War New York

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2015 The Cold Culture Wars: The Fight for Democratic Education in Post-War New York Brandon C. Williams Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Williams, Brandon C., "The Cold Culture Wars: The Fight for Democratic Education in Post-War New York" (2015). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 6955. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/6955 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Cold Culture Wars: The Fight for Democratic Education in Post-War New York Brandon C. Williams Dissertation submitted to the Eberly College of Arts & Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Elizabeth Fones-Wolf, Ph.D., Chair Ken-Fones-Wolf, Ph.D. James Siekmeier, Ph.D. Samuel Stack, Ph.D. Melissa Bingmann, Ph.D. Department of History Morgantown, WV 2015 Keywords: Democratic Education, Intercultural Education, Cold War, Civil Rights Copyright 2015 Brandon C. -

UC Santa Cruz UC Santa Cruz Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Santa Cruz UC Santa Cruz Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Organizing for Social Justice: Rank-and-File Teachers' Activism and Social Unionism in California, 1948-1978 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6b92b944 Author Smith, Sara R. Publication Date 2014 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ ORGANIZING FOR SOCIAL JUSTICE: RANK-AND-FILE TEACHERS’ ACTIVISM AND SOCIAL UNIONISM IN CALIFORNIA, 1948-1978 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements of the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in HISTORY with an emphasis in FEMINIST STUDIES by Sara R. Smith June 2014 The Dissertation of Sara R. Smith is approved: ______________________ Professor Dana Frank, Chair ______________________ Professor Barbara Epstein ______________________ Professor Deborah Gould ______________________ Tyrus Miller Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Copyright © by Sara R. Smith 2014 Table of Contents Abstract iv Acknowledgements vi Introduction 1 Chapter 1: 57 The Red School Teacher: Anti-Communism in the AFT and the Blacklistling of Teachers in Los Angeles, 1946-1960 Chapter 2: 151 “On Strike, Shut it Down!”: Faculty and the Black and Third World Student Strike at San Francisco State College, 1968-1969 Chapter 3: 260 Bringing Feminism into the Union: Feminism in the California Federation of Teachers in the 1970s Chapter 4: 363 “Gay Teachers Fight Back!”: Rank-and-File Gay and Lesbian Teachers’ Organizing against the Briggs Initiative, 1977-1978 Conclusion 453 Bibliography 463 iii Abstract Organizing for Social Justice: Rank-and-File Teachers’ Activism and Social Unionism in California, 1948-1978 Sara R. -

Executive Sessions of the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations of the Committee on Government Operations

S. Prt. 107–84 EXECUTIVE SESSIONS OF THE SENATE PERMANENT SUBCOMMITTEE ON INVESTIGATIONS OF THE COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENT OPERATIONS VOLUME 4 EIGHTY-THIRD CONGRESS FIRST SESSION 1953 ( MADE PUBLIC JANUARY 2003 Printed for the use of the Committee on Governmental Affairs U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 83–872 WASHINGTON : 2003 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Jan 31 2003 21:53 Mar 31, 2003 Jkt 083872 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 E:\HR\OC\83872PL.XXX 83872PL COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENTAL AFFAIRS 107TH CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION JOSEPH I. LIEBERMAN, Connecticut, Chairman CARL LEVIN, Michigan FRED THOMPSON, Tennessee DANIEL K. AKAKA, Hawaii TED STEVENS, Alaska RICHARD J. DURBIN, Illinois SUSAN M. COLLINS, Maine ROBERT G. TORRICELLI, New Jersey GEORGE V. VOINOVICH, Ohio MAX CLELAND, Georgia THAD COCHRAN, Mississippi THOMAS R. CARPER, Delaware ROBERT F. BENNETT, Utah MARK DAYTON, Minnesota JIM BUNNING, Kentucky PETER G. FITZGERALD, Illinois JOYCE A. RECHTSCHAFFEN, Staff Director and Counsel RICHARD A. HERTLING, Minority Staff Director DARLA D. CASSELL, Chief Clerk PERMANENT SUBCOMMITTEE ON INVESTIGATIONS CARL LEVIN, Michigan, Chairman DANIEL K. AKAKA, Hawaii, SUSAN M. COLLINS, Maine RICHARD J. DURBIN, Illinois TED STEVENS, Alaska ROBERT G. TORRICELLI, New Jersey GEORGE V. VOINOVICH, Ohio MAX CLELAND, Georgia THAD COCHRAN, Mississippi THOMAS R. CARPER, Delaware ROBERT F. BENNETT, Utah MARK DAYTON, Minnesota JIM BUNNING, Kentucky PETER G. FITZGERALD, Illinois ELISE J. BEAN, Staff Director and Chief Counsel KIM CORTHELL, Minority Staff Director MARY D. -

Finding Aid Prepared by David Kennaly Washington, D.C

THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS RARE BOOK AND SPECIAL COLLECTIONS DIVISION THE RADICAL PAMPHLET COLLECTION Finding aid prepared by David Kennaly Washington, D.C. - Library of Congress - 1995 LIBRARY OF CONGRESS RARE BOOK ANtI SPECIAL COLLECTIONS DIVISIONS RADICAL PAMPHLET COLLECTIONS The Radical Pamphlet Collection was acquired by the Library of Congress through purchase and exchange between 1977—81. Linear feet of shelf space occupied: 25 Number of items: Approx: 3465 Scope and Contents Note The Radical Pamphlet Collection spans the years 1870-1980 but is especially rich in the 1930-49 period. The collection includes pamphlets, newspapers, periodicals, broadsides, posters, cartoons, sheet music, and prints relating primarily to American communism, socialism, and anarchism. The largest part deals with the operations of the Communist Party, USA (CPUSA), its members, and various “front” organizations. Pamphlets chronicle the early development of the Party; the factional disputes of the 1920s between the Fosterites and the Lovestoneites; the Stalinization of the Party; the Popular Front; the united front against fascism; and the government investigation of the Communist Party in the post-World War Two period. Many of the pamphlets relate to the unsuccessful presidential campaigns of CP leaders Earl Browder and William Z. Foster. Earl Browder, party leader be—tween 1929—46, ran for President in 1936, 1940 and 1944; William Z. Foster, party leader between 1923—29, ran for President in 1928 and 1932. Pamphlets written by Browder and Foster in the l930s exemplify the Party’s desire to recruit the unemployed during the Great Depression by emphasizing social welfare programs and an isolationist foreign policy. -

Inhoudsopgave NIEUWSBRIEF 235 – 15.11.2015

Inhoudsopgave NIEUWSBRIEF 235 – 15.11.2015 Duitse scholen schrappen viering St-Maarten om moslimmigranten niet te kwetsen ....................................... 3 Veel immigranten hebben AIDS, syfilis, onbehandelde TBC” – gezondheidszorg in Duitsland op de knieën door asielchaos .................................................................................................................................................. 4 VN wil in 2030 verplicht biometrisch ID-bewijs voor ieder mens ....................................................................... 5 AfD politicus: ‘Duitsland op de rand van anarchie en een burgeroorlog’ .......................................................... 6 Staatsschuld stijgt met iedere immigrant bijna 80.000 euro .............................................................................. 7 Refugees not Welcome! Gedragen door het volk: De keiharde “vluchtelingen”politiek van Tsjechië ............... 8 Ook Nederlands Koningshuis gekaapt sinds 1940? .......................................................................................... 9 De Tweede Wereld Oorlog en haar geldmagnaten ......................................................................................... 22 Een zwarte dag voor Turkije ............................................................................................................................ 33 De waarheid over Gaddafi’s Libië .................................................................................................................... 35 Hillary Clinton ontmaskerd -

Rosary Hill Shooters to Clash With

VOL. 10, NO. 3 ROSARY HILL COLLEGE, BUFFALO, N. Y. MARCH 6, 1959 Dr. Bella Dodd, Ex-Communist, Lawyer To Speak on "Challenge To Americans" Few people in the United States today are more familiar with the objectives of the American Communist Party than Bella Dodd. Her knowledge is the result of first-hand experience, for Dr. Dodd was herself a member of the Communist Party for a number of years. Under the sponsorship of the Student Government Association, Dr. Dodd will speak at Rosary Hill on Sunday, March 8 at 8 :00 P. M. Her topic will be “Challenge to Americans.” Social .Problems Pose Dilemma After receiving her master’s degree from Teacher’s College Colgate Thirteen of Columbia University and her doctorate in law from New York Cheerleaders set for the conflict tonight: 1 to r. (front) To Offer Fest University, Bella Dodd was ad Katherine Collins, Kathleen Colquhoun. (back)) Patricia mitted to the New York State Bar Association in 1930. Four Heffernan, Carol Condon, Adele De Collibul Marsha THE COLGATE THIRTEEN, years prior to that she had be Randall and Molly Moore. known as “A m erica’s Unique come an instructor at Hunter Collegiate Singing Group,” will Uollege where she remained un sing at Rosary Hill on Friday til her resignation in 1938. Con Rosary H ill Shooters To Clash March 20. They will give their cern over social problems in concert in the Mafian Social Room at noon. this country and disgust with With Defending D YC Five the mediocrity of fellow Catho The Thirteen, formed in 1942 lics gradually drove Dr. -

Beggars on Horseback: Creating a Pan- African Power Paradigm for the 21St Century

Beggars On Horseback: Creating a Pan- African Power Paradigm for the 21st Century BEGGARS ON HORSEBACK CREATING A PAN AFRICAN POWER PARADIGM FOR THE 21ST CENTURY “Set a beggar on horseback and he’ll ride to the devil…”Tshiluba proverb FORWARD This is an Essay on Africa written on the eve of the 21st Century. Initially penned while the author was living in Africa as a cofounder of the Institute For the Development of Pan-African Policy, IDPAP, this essay was intended to serve as that NGO’s Geopolitical, and Economic Overview at the time. Though written in 1998-99, much of what now besets Africa, the AU, and African leaders have their roots in the Historical analysis presented here. Because of its length, “Beggars On Horseback” will be reproduced here in three parts, the last of which will address the current Western, U.S., and Chinese expropriation of Africa’s strategic minerals and resources under the Rubric of Globalization, and the “War on Islamic Extremism or “Terrorism.” DBW On the eve of the 21st century, Africa is up for sale at bargain basement prices. Many African states and Africa’s political leadership seem to engage in dead end diplomatic and economic activity because they perceive Africa as undeveloped rather than unorganized. African leaders have accepted the European concepts of power as hierarchical and external. Consequently, they have acquiesced to Eurocentric power paradigms, which marginalized Africa and wring their hands in despair while accepting the commandments of the IMP from on high. To some Africans desperate for hard currency and favorable foreign exchange selling Africa is just another game they play along with. -

F. Stone's Weekly

Should Communists Be Allowed to Teach? See Page 2. /. F. Stone's Weekly r. >rom'l mil.!, lie. VOL. I NUMBER 6 FEBRUARY 21, 1953 WASHINGTON, D. C 15 CENTS Anti-Zionism or Anti-Semitism? THE RUSSIANS FEAR WAR AND ARE SHUTTING the last win- at the crossroads of the world, where it can all too easily be dows on the West in preparation for it. That seems the most trampled by contending armies. It needs peace. It' cannot reasonable explanation for the anti-Zionist "show trials" which afford to fight the battles of the great Powers. For no nation have begun in the Soviet world. The Jews are the last people would a new war be a greater tragedy than for tiny Israel on in the U.S.S.R. and its satellites who still had some contact the edge of the petroleum fields which will be the first target with the West through such Jewish philanthropic organiza- of the air fleets. And no people needs peace more than the tions as the Joint Distribution Committee. Jews, a minority everywhere. In a long conflict, the Jews on Soviet policy never went beyond cultural autonomy; cen- the Soviet side will be suspected of pro-Westernism and on the tripetal nationalist tendencies are as much feared as in the days anti-Soviet side of pro-Communism. of the Czars. Nationalism (except at times for Russians) is officially stigmatized as "bourgeois," though the constant at- NONE OF us KNOW WHAT is REALLY HAPPENING IN EAST- tacks on "Titoism" in the satellites show how strongly it sur- ERN EUROPE. -

Charles A. Owen, Jr. Medieval Studies Library Catalog (Update in Progress)

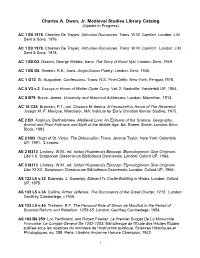

Charles A. Owen, Jr. Medieval Studies Library Catalog (Update in Progress) AC 1 E8 1976 Chretien De Troyes. Arthurian Romances. Trans. W.W. Comfort. London: J.M. Dent & Sons, 1976. AC 1 E8 1978 Chretien De Troyes. Arthurian Romances. Trans. W.W. Comfort. London: J.M. Dent & Sons, 1978. AC 1 E8 D3 Dasent, George Webbe, trans. The Story of Burnt Njal. London: Dent, 1949. AC 1 E8 G6 Gordon, R.K., trans. Anglo-Saxon Poetry. London: Dent, 1936. AC 1 G72 St. Augustine. Confessions. Trans. R.S. Pine-Coffin. New York: Penguin,1978. AC 5 V3 v.2 Essays in Honor of Walter Clyde Curry. Vol. 2. Nashville: Vanderbilt UP, 1954. AC 8 B79 Bryce, James. University and Historical Addresses. London: Macmillan, 1913. AC 15 C55 Brannan, P.T., ed. Classica Et Iberica: A Festschrift in Honor of The Reverend Joseph M.-F. Marique. Worcester, MA: Institute for Early Christian Iberian Studies, 1975. AE 2 B3 Anglicus, Bartholomew. Medieval Lore: An Epitome of the Science, Geography, Animal and Plant Folk-lore and Myth of the Middle Age. Ed. Robert Steele. London: Elliot Stock, 1893. AE 2 H83 Hugh of St. Victor. The Didascalion. Trans. Jerome Taylor. New York: Columbia UP, 1991. 2 copies. AE 2 I8313 Lindsay, W.M., ed. Isidori Hispalensis Episcopi: Etymologiarum Sive Originum. Libri I-X. Scriptorum Classicorum Bibliotheca Oxoniensis. London: Oxford UP, 1966. AE 2 I8313 Lindsay, W.M., ed. Isidori Hispalensis Episcopi: Etymologiarum Sive Originum. Libri XI-XX. Scriptorum Classicorum Bibliotheca Oxoniensis. London: Oxford UP, 1966. AS 122 L5 v.32 Edwards, J. Goronwy. -

Prudence and Controversy: the New York Public Library Responds to Post-War Anticommunist Pressures

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research Baruch College 2011 Prudence and Controversy: The New York Public Library Responds to Post-War Anticommunist Pressures Stephen Francoeur CUNY Bernard M Baruch College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/bb_pubs/13 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] 1 Prudence and Controversy: The New York Public Library Responds to Post-War Anticommunist Pressures Stephen Francoeur Baruch College [Post-print version accepted for publication in the September 2011 issue of Library & Information History. http://maney.co.uk/index.php/journals/lbh/] Abstract As the New York Public Library entered the post-war era in the late 1940s, its operations fell under the zealous scrutiny of self-styled ‗redhunters‘ intent upon rooting out library materials and staffers deemed un-American and politically subversive. The high point of attacks upon the New York Public Library came during the years 1947-1954, a period that witnessed the Soviet atomic bomb, the Berlin airlift, and the Korean War. This article charts the narrow and carefully wrought trail blazed by the library‘s leadership during that period. Through a reading of materials in the library archives, we see how political pressures were perceived and handled by library management and staff. We witness remarkable examples of brave defense of intellectual freedom alongside episodes of prudent equivocation. At the heart of the library‘s situation stood the contradictions between the principled commitments of individual library leaders and the practical political considerations underlying the library‘s viability.