Rural Energy Development Programme

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wszlvc56nv180322011948.Pdf

बिसिꅍन जि쥍लाका िंिोधधत लािग्राहीह셁को नामािली सि.न ि륍झौता क्र. ि.ं िंिोधन हुन ु ऩन े िंिोधधत नाम जि쥍ला गाविि/ नगरऩासलका िडा 1 51-29-7-0-001 Bal Bahadur Sunar Chet Narayan Sunar Argakhachi Mareng 7 2 51-41-2-0-005 Balkrishna Ghimire Shanta Ghimire Argakhachi Thada 2 3 51-34-3-0-002 Balkrishna Pariwar Bal krishna Darji Argakhachi Panena 3 4 51-3-5-0-007 Bhim Kami Punkali Kami Argakhachi Arghatos 5 5 51-8-8-0-019 Bhuwani Prasad Pandey Top Lal Pandey Argakhachi Bhagawati 8 6 51-37-8-0-003 Bil Bahadur warghare Khagi Kala Barghare Argakhachi Siddhara 8 7 51-35-4-0-012 Bir Bahadur B.K Kamala Bishowkarma Argakhachi Pokharathok 4 8 51-23-6-0-002 Bishnu Bahadur Chettri Kalpana Khatri Argakhachi Khana 6 9 51-37-2-0-002 Bishnu Prasad Bhushal Radha Bhushal Argakhachi Siddhara 2 10 51-8-2-0-001 Chet Narayan Ghimire Laxmi Ghimire Argakhachi Bhagawati 2 11 51-41-1-0-001 Dadhiram Paudel Damkala Paudel Argakhachi Thada 1 12 51-3-8-0-003 Damodar Bhushal Damodar Khanal Argakhachi Arghatos 8 13 51-36-1-0-004 Dashiram Chudali Bina Chudali Argakhachi Sandhikharka 1 14 51-42-4-0-001 Dashu Ram Pandey Kamala Pandey Argakhachi Thulapokhara 4 15 51-35-2-0-002 Deepak Raj Gautam Srijana Gyawali Argakhachi Pokharathok 2 16 51-29-1-0-003 Dil Bahadur Kunwar Dilaram Kunwar Argakhachi Mareng 1 17 51-37-9-0-002 Durga Budhathoki Bishna Budhathoki Argakhachi Siddhara 9 18 51-8-7-0-002 Durgadatta Pandey Goma Pandey Argakhachi Bhagawati 7 19 51-8-9-0-008 Ghaneshyam Pandey Ganga Pandey Argakhachi Bhagawati 9 20 51-19-4-0-001 Gomakala Adhikari Tikaram Adhikari Argakhachi Jukena 4 21 51-22-7-0-004 Govinda Bahadur Damai Thage Damai Argakhachi Kerunga 7 22 51-8-3-0-002 Gunakhar Pandey Mina Pandey Argakhachi Bhagawati 3 23 51-34-3-0-005 Hari Prasad Khanal Punkala Khanal Argakhachi Panena 3 24 51-8-9-0-007 Hutlal Pandey Putali Devi Pandey Argakhachi Bhagawati 9 25 51-8-2-0-005 Indramani Ghimire Putala Ghimire Argakhachi Bhagawati 2 26 51-36-1-0-008 Jamuna B.K. -

MCSP Annual Report

MCSP Annual Report FY 2018 October 1, 2017– September 30, 2018 Submission Date: November 6th, 2018 Cooperative Agreement No. AID-OAA-A-14-00028 Activity Start Date and End Date: October 2016 – April 2019 Activity Manager: Pavani Ram AOR: Nahed Matta Submitted by: Adhish Dhungana, Manager- Maternal & Child Survival Program Save the Children| Airport Gate Area, Shambhu Marg Kathmandu, Nepal GPO Box: 3394 Telephone: +977-1-4468130/4464803 Email: [email protected] This document was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). Acronyms BEmONC Basic Emergency Obstetric and Neonatal Care CHD Child Health Division CMA Community Medical Assistant CRS Contraceptive Retail Sales CSD Curative Service Division DDA Department of Drug Administration DHO District Health Office DoHS Department of Health Services DIP Detail Implementation Plan ENAP Every Newborn Action Plan FB IMNCI Facility Based Integrated Management of Neonatal and Childhood Illness FHD Family Health Division GoN Government of Nepal IMNCI Integrated Management of Neonatal and Childhood Illness MCSP Maternal and Child Survival Program M&E Monitoring and Evaluation MEL Monitoring, Evaluation, and Learning MNH Maternal and Newborn Health MNHI Maternal and Newborn Health Integration MoHP Ministry of Health and Population NCDA Nepal Chemist and Druggist Association NHRC Nepal Health Research Council NYI Newborns and Young Infants PI Principle Investigator PSBI Possible Severe Bacterial Infection PSD Partner for Social Development Nepal SBA Skilled Birth Attendant SCI Save the Children International SDG Sustainable Development Goal SNL Saving the Newborn Lives TAG Technical Advisory Group ToR Terms of Reference USAID United States Agency for International Development WHO World Health Organization WIRB Western Institutional Review Board Contents Acronyms 2 FINANCIAL INFORMATION Error! Bookmark not defined. -

District Profile - Kavrepalanchok (As of 10 May 2017) HRRP

District Profile - Kavrepalanchok (as of 10 May 2017) HRRP This district profile outlines the current activities by partner organisations (POs) in post-earthquake recovery and reconstruction. It is based on 4W and secondary data collected from POs on their recent activities pertaining to housing sector. Further, it captures a wide range of planned, ongoing and completed activities within the HRRP framework. For additional information, please refer to the HRRP dashboard. FACTS AND FIGURES Population: 381,9371 75 VDCs and 5 municipalities Damage Status - Private Structures Type of housing walls Kavrepalanchok National Mud-bonded bricks/stone 82% 41% Cement-bonded bricks/stone 14% 29% Damage Grade (3-5) 77,963 Other 4% 30% Damage Grade (1-2) 20,056 % of households who own 91% 85% Total 98,0192 their housing unit (Census 2011)1 NEWS & UPDATES 1. A total of 1,900 beneficiaries as per District Technical Office (DTO/DLPIU) have received the Second Tranche in Kavre. 114 beneficiaries within the total were supported by Partner Organizations. 2. Lack of proper orientations to the government officials and limited coordination between DLPIU engineers and POs technical staffs are the major reconstruction issues raised in the district. A joint workshop with all the district authorities, local government authorities and technical persons was agreed upon as a probable solution in HRRP Coordination Meeting dated April 12, 2017. HRRP - Kavrepalanchok HRRP © PARTNERS SUMMARY AND HIGHLIGHTS3 Partner Organisation Implementing Partner(s) ADRA NA 2,110 ARSOW -

Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal

SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics Acknowledgements The completion of both this and the earlier feasibility report follows extensive consultation with the National Planning Commission, Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), World Food Programme (WFP), UNICEF, World Bank, and New ERA, together with members of the Statistics and Evidence for Policy, Planning and Results (SEPPR) working group from the International Development Partners Group (IDPG) and made up of people from Asian Development Bank (ADB), Department for International Development (DFID), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), UNICEF and United States Agency for International Development (USAID), WFP, and the World Bank. WFP, UNICEF and the World Bank commissioned this research. The statistical analysis has been undertaken by Professor Stephen Haslett, Systemetrics Research Associates and Institute of Fundamental Sciences, Massey University, New Zealand and Associate Prof Geoffrey Jones, Dr. Maris Isidro and Alison Sefton of the Institute of Fundamental Sciences - Statistics, Massey University, New Zealand. We gratefully acknowledge the considerable assistance provided at all stages by the Central Bureau of Statistics. Special thanks to Bikash Bista, Rudra Suwal, Dilli Raj Joshi, Devendra Karanjit, Bed Dhakal, Lok Khatri and Pushpa Raj Paudel. See Appendix E for the full list of people consulted. First published: December 2014 Design and processed by: Print Communication, 4241355 ISBN: 978-9937-3000-976 Suggested citation: Haslett, S., Jones, G., Isidro, M., and Sefton, A. (2014) Small Area Estimation of Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal, Central Bureau of Statistics, National Planning Commissions Secretariat, World Food Programme, UNICEF and World Bank, Kathmandu, Nepal, December 2014. -

ANNUAL REPORT 2019 NEPAL PROGRAM Health for the Poorest ABBREVIATIONS

ANNUAL REPORT 2019 NEPAL PROGRAM Health for the Poorest ABBREVIATIONS • ANC: ANTE NATAL CARE • ANM: AUXILIARY NURSING MIDWIFE • BC: BIRTHING CENTER • BCC: BEHAVIOUR CHANGE COMMUNICATION • BYC: BHIMAPOKHARA YOUTH CLUB • CHSB: COMMUNITY HEALTH SCORE BOARD • CHU: COMMUNITY HEALTH UNIT • CP: CEREBRAL PALSY • DHIS: DISTRICT HEALTH INFORMATION SYSTEM • EDD: EXPECTED DATE OF DELIVERY • FCHV: FEMALE COMMUNITY HEALTH VOLUNTEER • HF: HEALTH FACILITY • HFOMC: HEALTH FACILITY OPERATION MANAGEMENT COMMITTEE • HP: HEALTH POST • ICRC: INTERNATIONAL COMMITTEE OF RED CROSS • INF: INTERNATIONAL NEPAL FELLOWSHIP • LMP: LAST MENSTRUAL PERIOD • MG: MOTHERS’ GROUP • MNH: MATERNAL AND NEONATAL HEALTH • NGO: NON-GOVERNMENTAL ORGANIZATION • NTD: NEGLECTED TROPICAL DISEASES • PHCC: PRIMARY HEALTH CARE CENTER • SATH: SELF-APPLIED TECHNIQUE FOR QUALITY HEALTH • SM: SOCIAL MOBILIZER • TOT: TRAINING OF TRAINERS • USG: ULTRASOUND SONO GRAPH • WASH: WATER, SANITATION AND HYGIENE TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE........................ 1 FOREWORD FROM THE COUNTRY COORDINATOR PAGE ....................... 3 FAIRMED IN NEPAL PAGE ....................... 4 ON-GOING PROJECTS : RURAL HEALTH IMPROVEMENT PROJECT PAGE ....................... 9 CASE STORY PAGE ......................11 ON-GOING PROJECTS : ESSENTIAL HEALTH PROJECT PAGE ......................16 CASE STORY PAGE ......................17 CASE STORY PAGE ......................18 COMPLETED PROJECTS : UPAKAR FOLLOWUP PAGE ......................20 FAIRMED IN DISABILITY INCLUSIVE DEVELOPMENT PAGE ......................22 FAIRMED FIELD -

Map of Dolakha District Show Ing Proposed Vdcs for Survey

Annex 3.6 Annex 3.6 Map of Dolakha district showing proposed VDCs for survey Source: NARMA Inception Report A - 53 Annex 3.7 Annex 3.7 Summary of Periodic District Development Plans Outlay Districts Period Vision Objectives Priorities (Rs in 'ooo) Kavrepalanchok 2000/01- Protection of natural Qualitative change in social condition (i) Development of physical 7,021,441 2006/07 resources, health, of people in general and backward class infrastructure; education; (ii) Children education, agriculture (children, women, Dalit, neglected and and women; (iii) Agriculture; (iv) and tourism down trodden) and remote area people Natural heritage; (v) Health services; development in particular; Increase in agricultural (vi) Institutional development and and industrial production; Tourism and development management; (vii) infrastructure development; Proper Tourism; (viii) Industrial management and utilization of natural development; (ix) Development of resources. backward class and region; (x) Sports and culture Sindhuli Mahottari Ramechhap 2000/01 – Sustainable social, Integrated development in (i) Physical infrastructure (road, 2,131,888 2006/07 economic and socio-economic aspects; Overall electricity, communication), sustainable development of district by mobilizing alternative energy, residence and town development (Able, local resources; Development of human development, industry, mining and Prosperous and resources and information system; tourism; (ii) Education, culture and Civilized Capacity enhancement of local bodies sports; (III) Drinking -

Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA)

Chapter 3 Project Evaluation and Recommendations 3-1 Project Effect It is appropriate to implement the Project under Japan's Grant Aid Assistance, because the Project will have the following effects: (1) Direct Effects 1) Improvement of Educational Environment By replacing deteriorated classrooms, which are danger in structure, with rainwater leakage, and/or insufficient natural lighting and ventilation, with new ones of better quality, the Project will contribute to improving the education environment, which will be effective for improving internal efficiency. Furthermore, provision of toilets and water-supply facilities will greatly encourage the attendance of female teachers and students. Present(※) After Project Completion Usable classrooms in Target Districts 19,177 classrooms 21,707 classrooms Number of Students accommodated in the 709,410 students 835,820 students usable classrooms ※ Including the classrooms to be constructed under BPEP-II by July 2004 2) Improvement of Teacher Training Environment By constructing exclusive facilities for Resource Centres, the Project will contribute to activating teacher training and information-sharing, which will lead to improved quality of education. (2) Indirect Effects 1) Enhancement of Community Participation to Education Community participation in overall primary school management activities will be enhanced through participation in this construction project and by receiving guidance on various educational matters from the government. 91 3-2 Recommendations For the effective implementation of the project, it is recommended that HMG of Nepal take the following actions: 1) Coordination with other donors As and when necessary for the effective implementation of the Project, the DOE should ensure effective coordination with the CIP donors in terms of the CIP components including the allocation of target districts. -

VBST Short List

1 आिेदकको दर्ा ा न륍बर नागररकर्ा न륍बर नाम थायी जि쥍ला गा.वि.स. बािुको नाम ईभेꅍट ID 10002 2632 SUMAN BHATTARAI KATHMANDU KATHMANDU M.N.P. KEDAR PRASAD BHATTARAI 136880 10003 28733 KABIN PRAJAPATI BHAKTAPUR BHAKTAPUR N.P. SITA RAM PRAJAPATI 136882 10008 271060/7240/5583 SUDESH MANANDHAR KATHMANDU KATHMANDU M.N.P. SHREE KRISHNA MANANDHAR 136890 10011 9135 SAMERRR NAKARMI KATHMANDU KATHMANDU M.N.P. BASANTA KUMAR NAKARMI 136943 10014 407/11592 NANI MAYA BASNET DOLAKHA BHIMESWOR N.P. SHREE YAGA BAHADUR BASNET136951 10015 62032/450 USHA ADHIJARI KAVRE PANCHKHAL BHOLA NATH ADHIKARI 136952 10017 411001/71853 MANASH THAPA GULMI TAMGHAS KASHER BAHADUR THAPA 136954 10018 44874 RAJ KUMAR LAMICHHANE PARBAT TILAHAR KRISHNA BAHADUR LAMICHHANE136957 10021 711034/173 KESHAB RAJ BHATTA BAJHANG BANJH JANAK LAL BHATTA 136964 10023 1581 MANDEEP SHRESTHA SIRAHA SIRAHA N.P. KUMAR MAN SHRESTHA 136969 2 आिेदकको दर्ा ा न륍बर नागररकर्ा न륍बर नाम थायी जि쥍ला गा.वि.स. बािुको नाम ईभेꅍट ID 10024 283027/3 SHREE KRISHNA GHARTI LALITPUR GODAWARI DURGA BAHADUR GHARTI 136971 10025 60-01-71-00189 CHANDRA KAMI JUMLA PATARASI JAYA LAL KAMI 136974 10026 151086/205 PRABIN YADAV DHANUSHA MARCHAIJHITAKAIYA JAYA NARAYAN YADAV 136976 10030 1012/81328 SABINA NAGARKOTI KATHMANDU DAANCHHI HARI KRISHNA NAGARKOTI 136984 10032 1039/16713 BIRENDRA PRASAD GUPTABARA KARAIYA SAMBHU SHA KANU 136988 10033 28-01-71-05846 SURESH JOSHI LALITPUR LALITPUR U.M.N.P. RAJU JOSHI 136990 10034 331071/6889 BIJAYA PRASAD YADAV BARA RAUWAHI RAM YAKWAL PRASAD YADAV 136993 10036 071024/932 DIPENDRA BHUJEL DHANKUTA TANKHUWA LOCHAN BAHADUR BHUJEL 136996 10037 28-01-067-01720 SABIN K.C. -

2015 Nepal Earthquake Response Project Putting Older People First

2015 Nepal Earthquake Response Project PUTTING OLDER PEOPLE FIRST A Special newsletter produced by HelpAge to mark the first four months of the April 2015 Earthquake CONTENTS Message from the Regional Director Editorial 1. HelpAge International in Nepal - 2015 Nepal Earthquake 1-4 Response Project (i) Unconditional Cash Transfers (UCTs) (ii) Health Interventions (iii) Inclusion- Protection Programme 2. Confidence Re-Born 5 3. Reflections from the Field 6 4. Humanitarian stakeholders working for Older People and 7-8 Persons with Disabilities in earthquake-affected districts 5. A Special Appeal to Humanitarian Agencies 9-11 Message from the Regional Director It is my great pleasure to contribute a few words to this HelpAge International Nepal e-newsletter being published to mark the four-month anniversary of the earthquake of 25 April, 2015, focusing on ‘Putting Older People First in a Humanitarian Response’. Of the eight million people in the 14 most earthquake-affected districts1, an estimated 650,000 are Older People over 60 years of age2, and are among the most at risk population in immediate need of humanitarian assistance. When factoring-in long-standing social, cultural and gender inequalities, the level of vulnerability is even higher among the 163,043 earthquake-affected older women3. In response to the earthquake, HelpAge, in collaboration with the government and in partnership with local NGOs, is implementing cash transfers, transitional shelter, health and inclusion-protection activities targeting affected Older People and their families. Furthermore, an Age and Disability Task Force-Nepal (ADTF-N)4 has been formed to highlight the specific needs and vulnerabilities of Older People and Persons with Disabilities and to put them at the centre of the earthquake recovery, rehabilitation and reconstruction efforts. -

TSLC PMT Result

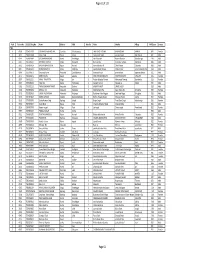

Page 62 of 132 Rank Token No SLC/SEE Reg No Name District Palika WardNo Father Mother Village PMTScore Gender TSLC 1 42060 7574O15075 SOBHA BOHARA BOHARA Darchula Rithachaupata 3 HARI SINGH BOHARA BIMA BOHARA AMKUR 890.1 Female 2 39231 7569013048 Sanju Singh Bajura Gotree 9 Gyanendra Singh Jansara Singh Manikanda 902.7 Male 3 40574 7559004049 LOGAJAN BHANDARI Humla ShreeNagar 1 Hari Bhandari Amani Bhandari Bhandari gau 907 Male 4 40374 6560016016 DHANRAJ TAMATA Mugu Dhainakot 8 Bali Tamata Puni kala Tamata Dalitbada 908.2 Male 5 36515 7569004014 BHUVAN BAHADUR BK Bajura Martadi 3 Karna bahadur bk Dhauli lawar Chaurata 908.5 Male 6 43877 6960005019 NANDA SINGH B K Mugu Kotdanda 9 Jaya bahadur tiruwa Muga tiruwa Luee kotdanda mugu 910.4 Male 7 40945 7535076072 Saroj raut kurmi Rautahat GarudaBairiya 7 biswanath raut pramila devi pipariya dostiya 911.3 Male 8 42712 7569023079 NISHA BUDHa Bajura Sappata 6 GAN BAHADUR BUDHA AABHARI BUDHA CHUDARI 911.4 Female 9 35970 7260012119 RAMU TAMATATA Mugu Seri 5 Padam Bahadur Tamata Manamata Tamata Bamkanda 912.6 Female 10 36673 7375025003 Akbar Od Baitadi Pancheswor 3 Ganesh ram od Kalawati od Kalauti 915.4 Male 11 40529 7335011133 PRAMOD KUMAR PANDIT Rautahat Dharhari 5 MISHRI PANDIT URMILA DEVI 915.8 Male 12 42683 7525055002 BIMALA RAI Nuwakot Madanpur 4 Man Bahadur Rai Gauri Maya Rai Ghodghad 915.9 Female 13 42758 7525055016 SABIN AALE MAGAR Nuwakot Madanpur 4 Raj Kumar Aale Magqar Devi Aale Magar Ghodghad 915.9 Male 14 42459 7217094014 SOBHA DHAKAL Dolakha GhangSukathokar 2 Bishnu Prasad Dhakal -

![NEPAL: Kabhrepalanchok - Operational Presence Map [As of 14 July 2015]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3032/nepal-kabhrepalanchok-operational-presence-map-as-of-14-july-2015-2093032.webp)

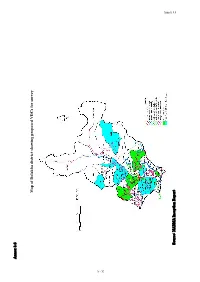

NEPAL: Kabhrepalanchok - Operational Presence Map [As of 14 July 2015]

NEPAL: Kabhrepalanchok - Operational Presence Map [as of 14 July 2015] Gairi Bisauna Deupur Baluwa Pati Naldhun Mahadevsthan Mandan Naya Gaun Deupur Chandeni Mandan 86 Jaisithok Mandan Partners working in Kabhrepalanchok Anekot Tukuchanala Devitar Jyamdi Mandan Ugrachandinala Saping Bekhsimle Ghartigaon Hoksebazar Simthali Rabiopi Bhumlutar 1-5 6-10 11-15 16-20 21-35 Nasikasthan Sanga Banepa Municipality Chaubas Panchkhal Dolalghat Ugratara Janagal Dhulikhel Municipality Sathigharbhagawati Sanuwangthali Phalete Mahendrajyoti Bansdol Kabhrenitya Chandeshwari Nangregagarche Baluwadeubhumi Kharelthok Salle Blullu Ryale Bihawar No. of implementing partners by Sharada (Batase) Koshidekha Kolanti Ghusenisiwalaye Majhipheda Panauti Municipality Patlekhet Gotpani cluster Sangkhupatichaur Mathurapati Phulbari Kushadevi Methinkot Chauri Pokhari Birtadeurali Syampati Simalchaur Sarsyunkharka Kapali Bhumaedanda Health 37 Balthali Purana Gaun Pokhari Kattike Deurali Chalalganeshsthan Daraunepokhari Kanpur Kalapani Sarmathali Dapcha Chatraebangha Dapcha Khanalthok Boldephadiche Chyasingkharka Katunjebesi Madankundari Shelter and NFI 23 Dhungkharka Bahrabisae Pokhari Narayansthan Thulo Parsel Bhugdeu Mahankalchaur Khaharepangu Kuruwas Chapakhori Kharpachok Protection 22 Shikhar Ambote Sisakhani Chyamrangbesi Mahadevtar Sipali Chilaune Mangaltar Mechchhe WASH 13 Phalametar Walting Saldhara Bhimkhori Education Milche Dandagaun 7 Phoksingtar Budhakhani Early Recovery 1 Salme Taldhunga Gokule Ghartichhap Wanakhu IMPLEMENTING PARTNERS BY CLUSTER Early Recovery -

Conducting a Study to Access the Effectiveness of Investment in Hills

His Majesty's Government National Planning Commission Secretariat (NPCS) Singha Ourbar, Kathmandu: '*'tt" '* '.'* '*I<: '* FINAL p '* '* For '* Conducting a study to assess the effectivene,s's a/investment '*'* '* In '* '* HillS' Leasehold ForestfY and/orage Development Project (HLFP1)P) '* '* '*'* '*'* '* '* *it" '* '* June, nepal p, Ltd, J'V'with* 'k Nepal~ P. 0, Sanepa, lalitpur Nepal ~ Tel. 523277,534221 Fax. 977-1 .~ e-mail: [email protected] ~ Web. www.viewnepatcomlbdanepal ~: - .'f( ~~~~~~--------------~--~~----~----~----------------~---*11: . ACKNOWLEDGEMENT This Final Report on Hills Leasehold Forestry and Forage Development Project (HLFFDP has been prepared under the contract agreement between National Planning Commission (NPC) and JV ofBDA nepal P. Ltd. and GOEC. This report has been prepared by the consultant after the extensive documentary consultation! study.. The consultant would like to express their gratitude to I would recall with gratitude for the t comments provided by Shri Shi'\b\.Chandra Shrestha (Joint Secretary on the CMED), DFo-- lIan Arval (Joist SetretaFV NJ!q and Mr. Sekhar Karki (CMED) was instrumental in bringing this study to this stage. He deserves more than a simple appreciation. Similarly, other senior members ofthe CMED were equally helpful at every stage of the project work, to whom I express my deep appreciation. Last but not least I express my gratitude to ~-Bhoj Raj) --'. Ghimire member-secretary, NPC and through him to the NPC for providing this-- opportunity to undertake the study and other technical staffs for their valuable suggestions and co-operation in proceeding with the study. At last, we are gratefhl to all the local people and leaders who have rendered their valuable accompany to our field team during field survey.