Transit-Oriented Development Without Displacement: Strategies to Help Pacoima Businesses Thrive

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Qualified Opportunity Zoned-C2-Tier 4 Site for Sale

FOR SALE QUALIFIED OPPORTUNITY ZONED-C2-TIER 4 SITE FOR SALE LOS ANGELES, CA 90043 MARK ZAKARIAN CCIM | [email protected] | O: 213.221.1242 | C: 818.468.1377 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY OFFERING SUMMARY PROPERTY OVERVIEW We are pleased to present a site located on only 500 feet west of the iconic intersection of West Sale Price: Subject To Offer Slauson and Crenshaw Blvd. The intersection was recently renamed after the late rapper, activist, 3475 W. Slauson Ave; and entrepreneur, Nipsey Hussle. Address: 5752 Brynhurst Ave; 5748 Brynhurst Ave The sale consists of 3 contiguous parcels zoned C2-1VL with TOC Tier 4 designation. The site is APN(s): 5006-003-013;014;015 located in the Qualified opportunity Zone and is located in the heart of Detestation Crenshaw, an open air museum celebrating the identity of the community. Steps to the incoming, Crenshaw Lot Size: 21,000 SF Metro Line, Hyde Park Metro Station which connects to the LAX people mover. Zoning: LAC2 Call broker for pricing, terms and co-op broker compensation information. TOC Tier: 4 -----------------------------------------------Seller Financing Available------------------------------------------------- Number Of Units Allowed: 95 ***PLEASE DO NOT DISTURB TENANTS. Buyer to perform its own investigations regarding zoning and number of buildable units. Neither Agents, Brokers, or Owners make any representations Qualified Opportunity Zone: Yes regarding the information presented herein. *** 3475 W SLAUSON AVE; 5748-52 BRYNHURST AVE. 2 LOS ANGELES, CA 90043 ADDITIONAL PHOTOS 3475 W SLAUSON AVE; 5748-52 BRYNHURST AVE. 3 LOS ANGELES, CA 90043 2019 CRENSHAW LAX METRO LINE The Hyde Park (formerly Crenshaw/Slauson) station is the only street-level station along the Cren- shaw/LAX Line. -

2012 Rail~Volution Program

CONFERENCE PROGRAM October 14-17, 2012 Los Angeles, California $UXSVSHDNHUVDW 5DLOYROXWLRQ Ellen Greenberg &RPSOHWH&RUULGRUV$9DOXDEOH C O N T E N T S &RPPXQLW\$VVHW Welcome to Los Angeles, California........................1 0RQGD\ ±$0 About the Conference .............................................2 The Loews Hollywood Hotel ...................................4 Anthony Bruzzone *HWWLQJWKH0RVW)URP<RXU What Will You Find at Rail~Volution?......................6 ([LVWLQJ7UDQVLW6\VWHP Workshop Formats ..................................................7 7XHVGD\ ±30 Workshop Themes...................................................7 Conference at a Glance ...........................................8 Darby Watson Plenary Speakers...................................................12 &RPSOHWH6WUHHWV:KHQ&DUV %LNHV3HGVDQG7UDQVLW3OD\1LFH 7XHVGD\ S C H E D U L E O F E V E N T S ±30 Saturday, October 13..............................................15 Sunday, October 14 ................................................15 Monday, October 15...............................................16 Tuesday, October 16 ..............................................27 3HOOL&ODUNH3HOOL$UFKLWHFWV Wednesday, October 17.........................................39 7UDQVED\7UDQVLW&HQWHU6DQ)UDQFLVFR&$ Mobile Workshops ................................................46 Acknowledgements..............................................49 $UXSLVDQLQGHSHQGHQW¿UPRIGHVLJQHUVSODQQHUV Conference Exhibitors............................................52 Rail~Volution Sponsors .........................................54 -

Expo Line Transit Project Design

Item 31 ChiefChief CapitalCapital ManagementManagement OfficerOfficer ReportReport February 19, 2009 MetroMetro GoldGold LineLine EastsideEastside ExtensionExtension ProjectProject UpdateUpdate FebruaryFebruary 19,19, 20092009 • 6 Mile Alignment • 1.7 Miles of Tunnel • 8 Stations (6 At-grade & 2 Underground) • Park & Ride Facility • Direct Connection to the Pasadena Metro Gold Line • $898.8 million • On-Time/Within Budget • Opens in Mid-2009 Gold Line 2 MetroMetro GoldGold LineLine EastsideEastside ExtensionExtension OverallOverall ConstructionConstruction ProgressProgress • Construction began in July 2004. As of mid-February 2009, the Project is over 94% complete. • The Contractor has worked over 3.8 million hours without a lost-time accident. • Construction of the two underground stations at 1st/Boyle and 1st/Soto is 91% complete. • Construction of the six at-grade stations is 78% complete. • Systems installation is 93% complete. Gold Line 3 MetroMetro GoldGold LineLine EastsideEastside ExtensionExtension OverallOverall ConstructionConstruction ProgressProgress RemainingRemaining WorkWork 2008 2009 2010 ACTIVITY JFMAMJJASONDJFMAMJJASONDJFMAMJ 1st/Boyle & 1st/Soto Station Boyle Heights/Mariachi Plaza & Soto Stations Architecture & 1st/Alameda Site Finishes Little Tokyo/Arts District Station 1st/Utah Pico/Aliso Station Indiana Indiana Station 3rd/Ford Maravilla Station 3rd/Mednik East LA Civic Station Pomona/Atlantic Atlantic Station Pomona/Atlantic Parking Structure 1st Street Bridge Widening Third Party Interfaces LAUSD Re-Build Ramona -

BOYLE HEIGHTS Community Plan Community Los Angeles City Planning City Angeles Los Draft Plan-Adoption Pending

Los Angeles City Planning BOYLE HEIGHTS Community Plan Draft Plan - Adoption Pending DRAFT November 19, 2018 November DRAFT Summer 2020 DRAFT DRAFT Summer 2020 Summer DRAFT Boyle Heights Plan TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 1 Introduction & Community Profile 1 Chapter 4 Public Realm & Open Space 39 Readers’ Guide 3 Goals and Policies 40 Plan Vision 4 Background and Relationshipto Other Plans 6 Chapter 5 Implementation 44 Community Profile 8 The Implementation Process 45 Goals and Policies 45 Guiding Principles 12 General Plan Land Use Designations 46 Zoning Regulations 46 Chapter 2 Land Use & Urban Form 17 Community Benefits System 46 Community Plan Amendments 46 Goals and Policies 18 Housing and Complete Neighborhoods 18 Implementation Programs 47 Community Centers and Corridors 21 Sources of Funding 47 Jobs and Economic Development 23 Reader’s Guide to the Implementation Tables 47 Urban Form 25 Acronyms for Agencies 48 Cultural and Historic Resources 27 Future Implementation Actions 49 Wellness and Sustainability 30 Established Programs 49 Future Implementation Actions 52 Chapter 3 Mobility & Connectivity 33 Proposed Programs 52 Goals and Policies 34 Appendix: Relationship to Other Plans DRAFT Summer 2020 Summer DRAFT Boyle Heights Plan Image: Shutterstock Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION & COMMUNITY PROFILE DRAFT Summer 2020 DRAFT Boyle Heights Plan | CH 1: Introduction & Community Profile | 2 THIS PAGE IS INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK DRAFT Summer 2020 DRAFT READERS’ GUIDE The Community Plan is a document that represents the land use vision and values for a distinct geography. A main function of the Community Plan is to guide decision-making with respect to land uses. This includes guidance for legislative decisions, such as adoption of overlay zones or supplemental development regulations, as well as amendments to the land use or zoning maps. -

LOS ANGELES COUNTY METROPOLITAN TRANSPORTATION AUTHORITY BID TABULATION Bid No.: PS11064106 Integrated Waste Management Services

LOS ANGELES COUNTY METROPOLITAN TRANSPORTATION AUTHORITY BID TABULATION Bid No.: PS11064106 Integrated Waste Management Services Bids Out: 11/29/10 Total 25 Bids Opened: 01/25/11 Total 3 Advertisement Date(s): 11/29/10 Newspaper: Passenger Transport American Reclamation Inc. Athens Service Waste Resources, Inc. Type of No. of Sector Location Container Containers Pick-Up Day(s) Cost Fees Total Cost Cost Fees Total Cost Cost Fees Total Cost BUS OPERATIONS Bus 3 cubic yard Locations Location 106 Wilshire Customer Svc. (cyd) 1 Mon $900.00 $90.00 $990.00 $13.85 $1.38 $15.23 $62.55 $6.26 $68.81 Location 512 3 cyd 2 Mon $1,800.00 $180.00 $1,980.00 $27.92 $2.79 $30.71 $125.10 $12.51 $137.61 Location 512 3 cyd 1 Mon-Tue-Wed $1,800.00 $180.00 $1,980.00 $40.15 $4.02 $44.17 $187.65 $18.77 $206.42 South Park 40 cyd 1 On call $15,480.00 $1,548.00 $17,028.00 $285.00 $28.50 $313.50 $275.00 $27.50 $302.50 South Park 3 cyd 7 Mon thru Fri $20,580.00 $2,058.00 $22,638.00 $395.31 $39.53 $434.84 $2,200.00 $220.00 $2,420.00 South Park 40 cyd 1 On call $15,480.00 $1,548.00 $17,028.00 $285.00 $28.50 $313.50 $275.00 $27.50 $302.50 Vernon Yard 3 cyd 3 Mon and Thu $3,528.00 $391.96 $3,919.96 $75.69 $8.41 $84.10 $375.30 $37.53 $412.83 Vernon Yard 3 cyd 3 On call $1,764.00 $195.98 $1,959.98 $150.00 $16.65 $166.65 $47.00 $4.70 $51.70 Gateway Division 1 3 cyd 6 Mon thru Sat $21,168.00 $2,116.80 $23,284.80 $406.62 $40.66 $447.28 $2,200.00 $320.00 $2,520.00 Division 2 3 cyd 8 Mon thru Sat $28,200.00 $2,820.00 $31,020.00 $516.92 $51.69 $568.61 $2,600.00 $260.00 $2,860.00 -

Joint International Light Rail Conference

TRANSPORTATION RESEARCH Number E-C145 July 2010 Joint International Light Rail Conference Growth and Renewal April 19–21, 2009 Los Angeles, California Cosponsored by Transportation Research Board American Public Transportation Association TRANSPORTATION RESEARCH BOARD 2010 EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE OFFICERS Chair: Michael R. Morris, Director of Transportation, North Central Texas Council of Governments, Arlington Vice Chair: Neil J. Pedersen, Administrator, Maryland State Highway Administration, Baltimore Division Chair for NRC Oversight: C. Michael Walton, Ernest H. Cockrell Centennial Chair in Engineering, University of Texas, Austin Executive Director: Robert E. Skinner, Jr., Transportation Research Board TRANSPORTATION RESEARCH BOARD 2010–2011 TECHNICAL ACTIVITIES COUNCIL Chair: Robert C. Johns, Associate Administrator and Director, Volpe National Transportation Systems Center, Cambridge, Massachusetts Technical Activities Director: Mark R. Norman, Transportation Research Board Jeannie G. Beckett, Director of Operations, Port of Tacoma, Washington, Marine Group Chair Cindy J. Burbank, National Planning and Environment Practice Leader, PB, Washington, D.C., Policy and Organization Group Chair Ronald R. Knipling, Principal, safetyforthelonghaul.com, Arlington, Virginia, System Users Group Chair Edward V. A. Kussy, Partner, Nossaman, LLP, Washington, D.C., Legal Resources Group Chair Peter B. Mandle, Director, Jacobs Consultancy, Inc., Burlingame, California, Aviation Group Chair Mary Lou Ralls, Principal, Ralls Newman, LLC, Austin, Texas, Design and Construction Group Chair Daniel L. Roth, Managing Director, Ernst & Young Orenda Corporate Finance, Inc., Montreal, Quebec, Canada, Rail Group Chair Steven Silkunas, Director of Business Development, Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Public Transportation Group Chair Peter F. Swan, Assistant Professor of Logistics and Operations Management, Pennsylvania State, Harrisburg, Middletown, Pennsylvania, Freight Systems Group Chair Katherine F. -

2018 Energy & Resource Report Table of Contents

2018 ENERGY & RESOURCE REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS Message from the CEO............................................. 4 Message from the Incoming Board Chair ......................... 5 Executive Summary ................................................ 6 Methodology ...................................................... 8 Operational Efficiency ............................................. 10 Air Quality ......................................................... 14 Highlight: Environmental Justice .............................. 18 Climate ............................................................ 20 Highlight: Green Procurement ................................ 24 Community ........................................................ 26 Highlight: Sustainability Council .............................. 30 Energy ............................................................. 32 Highlight: Life of a Sustainable Project ....................... 36 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Water .............................................................. 38 This document was prepared by Cumming and Lentini Design & Marketing under Highlight: Sustaining Creativity ............................... 42 contract through the Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority Waste .............................................................. 44 (Metro) administered by Metro’s Environmental Compliance and Sustainability Department. Technical information was provided by the following Metro Next Stop .......................................................... 48 Departments: Building -

Framework of Sustainable Transit Communities

FRAMEWORK OF SUSTAINABLE TRANSIT COMMUNITIES OFFICE OF THE MAYOR, CITY OF LOS ANGELES FEBRUARY 2011 This is a project for the City of Los Angeles (City) with funding provided by the Southern California Association of Governments’ (SCAG) Compass Blueprint Program. Compass Blueprint assists Southern California cities and other organizations in evaluating planning options and stimulating development consistent with the region’s goals. Compass Blueprint tools support visioning efforts, infill analyses, and marketing and communications programs. The preparation of this report has been financed in part through grant(s) from the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) and Federal Transit Administration (FTA), U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) in accordance with the provision under the Metropolitan Planning Program as set forth in Section 104(f) of Title 23 of the U.S. Code. The contents of this report reflect the views of the author, who is responsible for the facts and accuracy of the data presented herein. The contents do not necessarily reflect the official views or policies of SCAG, DOT, or the State of California. This report does not constitute a standard, specification, or regulation. SCAG shall not be responsible for the City’s future use or adaptation of the report. FRAMEWORK OF SUSTAINABLE TRANSIT COMMUNITIES OFFICE OF THE MAYOR, CITY OF LOS ANGELES FEBRUARY 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 3 OVERVIEW OF THE FRAMEWORK 4 Mix and Vitality of Uses 9 Well-Defined Sense of Place 11 Walkability and the Pedestrian Realm 14 Multimodal -

Art Guide a Tour of Metro’S Artwork Metro Commissions Artists to Create Engaging and Thought-Provoking Artworks to Make Your Journey More Inviting and Pleasurable

metro.net Art Guide A tour of Metro’s artwork Metro commissions artists to create engaging and thought-provoking artworks to make your journey more inviting and pleasurable. The artworks weave a multi-layered cultural tapestry that mirrors Los Angeles County’s rich contemporary and popular cultures. Established in 1989, the Metro Art program has commissioned over 250 artists for a wide variety of both temporary and permanent projects. explore Artists are selected through a peer review process with community input; all works are created especially for their transit related sites. This guide is intended to help you discover artworks throughout the Metro system. For more detailed information on the artwork and the artists, please visit metro.net/art. Artwork copyrighted, all rights reserved. Metro Lines and Transitways Metro Contents Art’s a Trip. Art’s a Trip Metro Environments Free Metro Rail Tours Tours are o=ered the >rst Saturday, > Thursdays – Meet at 7pm at Sunday and Thursday of each month. the street level entrance to the Metro Rail Metro Customer Center It’s free. It’s provocative. The tours are roundtrip and last Hollywood/Highland Metro l Metro Red Line Metro Vehicles It’s a great ride. approximately two hours. Rail Station. Union Station Bus Plaza l Metro Purple Line Tours for groups of 15 or more are > Saturdays – Meet at 10am at > Each tour is unique, visits l Metro Gold Line Metro Headquarters available by special arrangement. the street level entrance to the di=erent stations and is led Metro Division 3 Hollywood/Highland Metro by a member of the Metro Art l Metro Blue Line Call 213 .922.2738 for information Rail Station. -

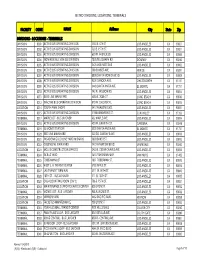

Master List of Mta Divisions Locations Stations 073009

METRO DIVISIONS, LOCATIONS, TERMINALS FACILITY CODE NAME Address City State Zip DIVISIONS - LOCATIONS - TERMINALS DIVISION 0001 ACTIVE BUS OPERATING DIVISION 1130 E. 6TH ST LOS ANGELES CA 90021 DIVISION 0002 ACTIVE BUS OPERATING DIVISION 720 E. 15TH ST. LOS ANGELES CA 90021 DIVISION 0003 ACTIVE BUS OPERATING DIVISION 630 W. AVENUE 28 LOS ANGELES CA 90065 DIVISION 0004 NON-REVENUE VEHICLE DIVISION 7878 TELEGRAPH RD. DOWNEY CA 90240 DIVISION 0005 ACTIVE BUS OPERATING DIVISION 5425 VAN NESS AVE. LOS ANGELES CA 90062 DIVISION 0006 ACTIVE BUS OPERATING DIVISION 100 SUNSET AVE. VENICE CA 90291 DIVISION 0007 ACTIVE BUS OPERATING DIVISION 8800 SANTA MONICA BLVD. LOS ANGELES CA 90069 DIVISION 0008 ACTIVE BUS OPERATING DIVISION 9201 CANOGA AVE. CHATSWORTH CA 91311 DIVISION 0009 ACTIVE BUS OPERATING DIVISION 3449 SANTA ANITA AVE. EL MONTE CA 91731 DIVISION 0010 ACTIVE BUS OPERATING DIVISION 742 N. MISSION RD. LOS ANGELES CA 90033 DIVISION 0011 BLUE LINE MAIN YARD 4350 E. 208th ST. LONG BEACH CA 90810 DIVISION 0012 INACTIVE BUS OPERATING DIVISION 970 W. CHESTER PL. LONG BEACH CA 90813 LOCATION 0014 SOUTH PARK SHOPS 5413 AVALON BLVD. LOS ANGELES CA 90011 DIVISION 0015 ACTIVE BUS OPERATING DIVISION 11900 BRANFORD ST. SUN VALLEY CA 91352 TERMINAL 0017 MAPLE LOT - BUS LAYOVER 632 MAPLE AVE. LOS ANGELES CA 90014 DIVISION 0018 ACTIVE BUS OPERATING DIVISION 450 W. GRIFFITH ST. GARDENA CA 90248 TERMINAL 0019 EL MONTE STATION 3501 SANTA ANITA AVE. EL MONTE CA 91731 DIVISION 0020 RED LINE MAIN YARD 320 SO. SANTA FE AVE. LOS ANGELES CA 90013 DIVISION 0021 PASADENA GOLD LINE YARD(MIDWAY) 1800 BAKER ST. -

Artist Citations

Downtown Fremont Public Art Program (Temporary Installation) – Metamorphosis Downloaded by Alina Kwak Thursday, December 15th 2016, 2:27pm Call ID: 990676 Artist ID: 7754 Status: Received Helle scharlingtodd Contact Partner Contact via Email [email protected] Phone Cell Web Site glassandmosaics.com Mailing Address . Custom Answers 2) Statement Regarding ThemeArtist must provide a written statement (up to 150 words) as part of their submittal explaining how their sculpture addresses and illustrates the theme. Art is like music, it stimulates the mind and the senses. With this in mind I build my pieces with emphasis on space, form, color, line, rhythm, and content. Artists are image makers and like the world's antennas, they feel, think and express reality. Momentarily I focus on "defining our spaces", like building a new society, using color, form and line as the building blocks. In addition to my public art projects I have developed a series of "color molecule" sculptures. The sculptures represent an homage to the smallest building block of life, the molecules. The theme is called "metamorphosis" which means change, and I see my work fitiing to the theme, as we all have metamorphed from molecules to a human being, so honoring the smallest entity in us seems allright. The work has semi circular motions, which gives a light feeling. The piece is 14' x 6;' x 6'. It is powder coated, the main color being turquise with colored glass inserted in the molecules. When the light shines through 3) Art Installation and De-Installation PlanPlease reference the attached site plan and provide an installation and de-installation plan and requirements for the attachment of the Artwork and the type of hardware to be used for the attachment. -

Fights for Census Equality Ahead of Census 2020, Assemblymember Reginald “Reggie” Bryon Jones-Sawyer, Sr

History professor Jonathan Meet Anthony (Tony) Abraha- Chism illuminates the words of Dr. ms, the man behind the Tweedl King in new book (See page A-9) app (See page A-9) VOL. LXXVV, NO. 49 • $1.00 + CA. Sales Tax THURSDAY, DECEMBER 12 - 18, 2013 VOL. LXXXV NO. 31, $1.00 +CA. Sales Tax“For Over “For Eighty Over Eighty Years Years, The Voice The Voiceof Our of CommunityOur Community Speaking Speaking for forItself Itself.” THURSDAY, AUGUST 1, 2019 The Clippers are Coming to the City of Inglewood The L.A. team unveils plans for new Inglewood Sports Arena. L.A. City Councilmember Marqueece Harris-Dawson and supporters rejoice, as the LA Metro Board voted unanimously to fund Destination Crenshaw. E. MESIYAH MCGINNIS / LA SENTINEL From Left, the City of Inglewood Mayor James T. Butts and L.A. Clippers Chairman Steve Ballmer at Clipper’s The Playbook event in Los Angeles. LAUREN FLOYD vealed yet another excit- Staff Writer ing development for fans of “The Clips”— a new Attention all local Los premiere sports arena in Angeles Clippers fans: Inglewood, CA. Even if Your time has arrived. Af- your blood runs in more COURTESY PHOTO ter years as the underdog, of a gold and purple hue, City Councilmember Marqueece Harris-Dawson edges closer to his vision of celebrating Black culture through art your team is now ranked this development is one as a landmark for Crenshaw Blvd. first in the NBA’s power to watch, not only for the rankings for the 2019- team, but for the city of BY SAYBIN ROBERSON granting $15 million to Des- celebrate Black Los - Angenomic development and 2020 season.