Movement, Knowledge, Emotion: Gay Activism and HIV/AIDS in Australia to Test Or Not to Test?: HIV Antibody Testing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abortion, Homosexuality and the Slippery Slope: Legislating ‘Moral’ Behaviour in South Australia

Abortion, Homosexuality and the Slippery Slope: Legislating ‘Moral’ Behaviour in South Australia Clare Parker BMusSt, BA(Hons) A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Discipline of History, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Adelaide. August 2013 ii Contents Contents ii Abstract iv Declaration vi Acknowledgements vii List of Abbreviations ix List of Figures x A Note on Terms xi Introduction 1 Chapter 1: ‘The Practice of Sound Morality’ 21 Policing Abortion and Homosexuality 24 Public Conversation 36 The Wowser State 44 Chapter 2: A Path to Abortion Law Reform 56 The 1930s: Doctors, Court Cases and Activism 57 World War II 65 The Effects of Thalidomide 70 Reform in Britain: A Seven Month Catalyst for South Australia 79 Chapter 3: The Abortion Debates 87 The Medical Profession 90 The Churches 94 Activism 102 Public Opinion and the Media 112 The Parliamentary Debates 118 Voting Patterns 129 iii Chapter 4: A Path to Homosexual Law Reform 139 Professional Publications and Prohibited Literature 140 Homosexual Visibility in Australia 150 The Death of Dr Duncan 160 Chapter 5: The Homosexuality Debates 166 Activism 167 The Churches and the Medical Profession 179 The Media and Public Opinion 185 The Parliamentary Debates 190 1973 to 1975 206 Conclusion 211 Moral Law Reform and the Public Interest 211 Progressive Reform in South Australia 220 The Slippery Slope 230 Bibliography 232 iv Abstract This thesis examines the circumstances that permitted South Australia’s pioneering legalisation of abortion and male homosexual acts in 1969 and 1972. It asks how and why, at that time in South Australian history, the state’s parliament was willing and able to relax controls over behaviours that were traditionally considered immoral. -

Political Overview

ECONOMIC AND POLITICAL OVERVIEW PHOTO: PAUL LOVELACE PHOTOGRAPHY Professor Ken Wiltshire AO Professor Ken Wiltshire is the JD Story Professor of Public Administration at the University of Queensland Business School. He is a Political long-time contributor to CEDA’s research and an honorary trustee. overview As Australia enters an election year in 2007, Ken Wiltshire examines the prospects for a long-established Coalition and an Opposition that has again rolled the leadership dice. 18 australian chief executive RETROSPECT 2006 Prime Minister and Costello as Treasurer. Opinion Politically, 2006 was a very curious and topsy-turvy polls and backbencher sentiment at the time vindi- … [Howard] became year. There was a phase where the driving forces cated his judgement. more pragmatic appeared to be the price of bananas and the depre- From this moment the Australian political than usual … dations of the orange-bellied parrot, and for a dynamic changed perceptibly. Howard had effec- nation that has never experienced a civil war there tively started the election campaign, and in the “ were plenty of domestic skirmishes, including same breath had put himself on notice that he culture, literacy, and history wars. By the end of the would have to win the election. Almost immedi- year both the government and the Opposition had ately he became even more pragmatic than usual, ” changed their policy stances on a wide range of and more flexible in policy considerations, espe- issues. cially in relation to issues that could divide his own Coalition. The defining moment For Kim Beazley and the ALP, Howard’s decision The defining moment in Australian politics was clearly not what they had wanted, despite their occurred on 31 July 2006 when Prime Minister claims to the contrary, but at least they now knew John Howard, in response to yet another effort to the lay of the battleground and could design appro- revive a transition of leadership to his Deputy Peter priate tactics. -

Ministerial Careers and Accountability in the Australian Commonwealth Government / Edited by Keith Dowding and Chris Lewis

AND MINISTERIAL CAREERS ACCOUNTABILITYIN THE AUSTRALIAN COMMONWEALTH GOVERNMENT AND MINISTERIAL CAREERS ACCOUNTABILITYIN THE AUSTRALIAN COMMONWEALTH GOVERNMENT Edited by Keith Dowding and Chris Lewis Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Ministerial careers and accountability in the Australian Commonwealth government / edited by Keith Dowding and Chris Lewis. ISBN: 9781922144003 (pbk.) 9781922144010 (ebook) Series: ANZSOG series Notes: Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: Politicians--Australia. Politicians--Australia--Ethical behavior. Political ethics--Australia. Politicians--Australia--Public opinion. Australia--Politics and government. Australia--Politics and government--Public opinion. Other Authors/Contributors: Dowding, Keith M. Lewis, Chris. Dewey Number: 324.220994 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2012 ANU E Press Contents 1. Hiring, Firing, Roles and Responsibilities. 1 Keith Dowding and Chris Lewis 2. Ministers as Ministries and the Logic of their Collective Action . 15 John Wanna 3. Predicting Cabinet Ministers: A psychological approach ..... 35 Michael Dalvean 4. Democratic Ambivalence? Ministerial attitudes to party and parliamentary scrutiny ........................... 67 James Walter 5. Ministerial Accountability to Parliament ................ 95 Phil Larkin 6. The Pattern of Forced Exits from the Ministry ........... 115 Keith Dowding, Chris Lewis and Adam Packer 7. Ministers and Scandals ......................... -

Engaging Iran Australian and Canadian Relations with the Islamic Republic Engaging Iran Australian and Canadian Relations with the Islamic Republic

Engaging Iran Australian and Canadian Relations with the Islamic Republic Engaging Iran Australian and Canadian Relations with the Islamic Republic Robert J. Bookmiller Gulf Research Center i_m(#ÆAk pA'v@uB Dubai, United Arab Emirates (_}A' !_g B/9lu( s{4'1q {xA' 1_{4 b|5 )smdA'c (uA'f'1_B%'=¡(/ *_D |w@_> TBMFT!HSDBF¡CEudA'sGu( XXXHSDBFeCudC'?B uG_GAE#'c`}A' i_m(#ÆAk pA'v@uB9f1s{5 )smdA'c (uA'f'1_B%'cAE/ i_m(#ÆAk pA'v@uBª E#'Gvp*E#'B!v,¢#'E#'1's{5%''tDu{xC)/_9%_(n{wGLi_m(#ÆAk pA'v@uAc8mBmA' , ¡dA'E#'c>EuA'&_{3A'B¢#'c}{3'(E#'c j{w*E#'cGuG{y*E#'c A"'E#'c CEudA%'eC_@c {3EE#'{4¢#_(9_,ud{3' i_m(#ÆAk pA'v@uBB`{wB¡}.0%'9{ymA'E/B`d{wA'¡>ismd{wd{3 *4#/b_dA{w{wdA'¡A_A'?uA' k pA'v@uBuCc,E9)1Eu{zA_(u`*E @1_{xA'!'1"'9u`*1's{5%''tD¡>)/1'==A'uA'f_,E i_m(#ÆA Gulf Research Center 187 Oud Metha Tower, 11th Floor, 303 Sheikh Rashid Road, P. O. Box 80758, Dubai, United Arab Emirates. Tel.: +971 4 324 7770 Fax: +971 3 324 7771 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.grc.ae First published 2009 i_m(#ÆAk pA'v@uB Gulf Research Center (_}A' !_g B/9lu( Dubai, United Arab Emirates s{4'1q {xA' 1_{4 b|5 )smdA'c (uA'f'1_B%'=¡(/ © Gulf Research Center 2009 *_D All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in |w@_> a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, TBMFT!HSDBF¡CEudA'sGu( XXXHSDBFeCudC'?B mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the Gulf Research Center. -

The Politics of Terrorism in Australia: Views from Within Michael Crowley Michael Crowley Is Senior Lecturer, School of Law and Justice at Edith Cowan University

80 The politics of terrorism in Australia: views from within Michael Crowley Michael Crowley is Senior Lecturer, School of Law and Justice at Edith Cowan University INTRODUCTION The views from within the Australian parliament on the response to the terrorist attacks in America on 11 September 2001 were enlightening, informative and mostly reassuring. These views highlighted the inbuilt strengths and weaknesses of our political system. The political response of these parliamentarians to those terrorist attacks had links to another time of crisis during World War Two when Australia turned from the United Kingdom (UK), the ‘mother country’, to the United States of America (USA) for military assistance against a looming Japanese invasion. Then the Australian Prime Minister John Curtin (1942) gave his ‘Call to America’ speech 1,QWKHPRUHWKDQVL[W\\HDUVVLQFHWKH Australian – American relationship has blossomed. It includes regular Australia-United 6WDWHV0LQLVWHULDO&RQVXOWDWLRQV $860,1 MRLQWPLOLWDU\H[HUFLVHVLQFOXGLQJIDFLOLWLHVVXFK as Pine Gap and visits by American naval units to Australia and, more recently, the start of an on-going rotation of US marines through Darwin. Australia’s response to the events of 11 September 2001 was in hindsight predictable. Despite Australia’s belief in its role DVDQLQGHSHQGHQWQDWLRQVWDWHLWVFLWL]HQVVWLOOFOLQJWRWKHFRDWWDLOVRIWKH%ULWLVK(PSLUH 7KH8QLRQ-DFNDGRUQVDFRUQHURIWKH$XVWUDOLDQÁDJDQGWKH4XHHQRI(QJODQGLVWKHWLWXODU head of state. So, whilst Australia hangs onto the perceived political comfort and stability of the English Crown, it is to America that Australia looks for its security. This article includes responses from a number of parliamentarian about the terrorist attacks on the USA on 11 September 2001. This attack was an abhorrent assault on the core values of democracy DQGIUHHGRPLQERWKQDWLRQV VHHIRUH[DPSOH$860,1 2) but the date has historical RYHUWRQHV2QWKDWGD\LQ3UHVLGHQW5LFKDUG1L[RQVXSSRUWHGWKHRYHUWKURZRIWKH democratically elected Chilean Government of Salvador Allende. -

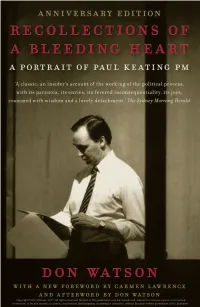

Copyright © Don Watson 2011. All Rights Reserved. No Part

Copyright © Don Watson 2011. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. ‘This is much more than a paeon of praise to Keating. There is wit and remarkable candour which puts it streets ahead of most political biogra- phies . a penetrating insight into a Labor prime minister. Despite the millions of words already written about Keating, it adds much.’ Mike Steketee, Weekend Australian ‘Watson’s book is neither biography nor history nor Watson’s personal journey nor a string of anecdotes, but a compound of all these things. It is the story of four tumultuous years told by an intelligent and curious insider, and no insider has ever done it better.’ Les Carlyon, Bulletin ‘. a subtle and sympathetic analysis of the many facets of the twenty- fourth prime minister; a narrative of high and low politics in the Keating years; and a compendium of the wit and wisdom of Don Watson . in future, when I am asked, “What was Paul Keating really like?” the answer must be, “Go read Don Watson.”’ Neal Blewett, Australian Book Review ‘This big book has reset the benchmark for political writing in this country, with its ability to entertain and appal at the same time . .’ Courier-Mail ‘. always absorbing, usually illuminating, frequently disturbing, often stimulating . remarkably frank . Every page is enlightened by Watson’s erudition.’ John Nethercote, Canberra Times ‘. an intriguing account of a time and a place and a man – vantage point that is so unusual, so close and by such an intelligent and partisan witness, as to make it unrivalled in the annals of Australian political writing.’ Ramona Koval ‘… a masterpiece … simply the best account of life, politics and combat inside the highest office in the land ever written.’ Michael Gordon, The Age ‘. -

ANNUAL REPORT 2018–19 NATIONAL LIBRARY of AUSTRALIA Annual Report 2018–19

2018–19 Annual Report Report Annual NATIONAL LIBRARY OF AUSTRALIA OF AUSTRALIA LIBRARY NATIONAL ANNUAL REPORT 2018–19 NATIONAL LIBRARY OF AUSTRALIA GOVERNANCE AND ACCOUNTABILTY i NATIONAL LIBRARY OF AUSTRALIA Annual Report 2018–19 NATIONAL LIBRARY OF AUSTRALIA 9 August 2019 The Hon. Paul Fletcher MP Minister for Communications, Cyber Safety and the Arts Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Dear Minister National Library of Australia Annual Report 2018–19 The Council, as the accountable authority of the National Library of Australia, has pleasure in submitting to you for presentation to each House of Parliament its annual report covering the period 1 July 2018 to 30 June 2019. Published by the National Library of Australia The Council approved this report at its meeting in Canberra on 9 August 2019. Parkes Place Canberra ACT 2600 The report is submitted to you in accordance with section 46 of the T 02 6262 1111 Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013. F 02 6257 1703 National Relay Service 133 677 We commend the annual report to you. nla.gov.au/policy/annual.html Yours sincerely ABN 28 346 858 075 © National Library of Australia 2019 ISSN 0313-1971 (print) 1443-2269 (online) National Library of Australia The Hon. Dr Brett Mason Dr Marie-Louise Ayres Annual report / National Library of Australia.–8th (1967/68)– Chair of Council Director-General Canberra: NLA, 1968––v.; 25 cm. Annual. Continues: National Library of Australia. Council. Annual report of the Council = ISSN 0069-0082. Report year ends 30 June. ISSN 0313-1971 = Annual report–National Library of Australia. -

The Tuckeys of Mandurah the Western Australian Historical

SYLLABlfS FOR 1961 MEETINGS The Western Australian The ordinary meetings of the Society are held in the Methodist Mission Hall, 283 Murray Street, Perth (near William Street Historical Society Incorporated corner), at 8 p.m. on the last Friday in each month. .JOlfRNilL AND PROCEEDINGS February 24th: Bishop Salvado and John Forrest, from the records of New Norcia, by Dom William, O.S.B. VoL V 1961 Part VllI March 24th: Annual General Meeting. April 28th: Goldfields Night. Recollections of pioneering days in Boulder City, by Mrs. Edith Acland Wiles. The Society does not hold itself responsible for statements made or opinions expressed by authors of the papers May 26th: Where was Abram Leeman's Island? by James H. published in this Journal. Turner. (Illustrated with coloured slides.) June 30th: The Development of the Hotel Industry in Western Australia, by J. E. Dolin. The Tuckeys of Mandurah July 28th: Sir John Forrest in National Politics, by Dr. F. K. Crowley. By J. H. M. HONNIBALL, B.A. August 25th: The History of Bolgart, by Mrs. Rica Erickson and G. R. Kemp. My own memories of Mandurah go back less than twenty years, but the quiet town left even a small boy on annual holidays September 29th: The History of Wongan Hills, by R. B. Ackland. with distmct impressions. Swimming and fishing were attractions October 27th: 100 Years of Local Government at Albany, by for every visitor; But other remarkable features of the place were Robert Stephens. the slowly clanking windmills, spreading tuart trees, old stone November 24th: Readings from prize-Winning essays in the Lee houses with grape vines and fig and mulberry trees in their Steere Award. -

4. Treatment Action

4. Treatment Action The first hope of a possible course of treatment for HIV came in the second half of the 1980s. Azidothymidine or Zidovudine (AZT) was originally developed in the 1960s for the treatment of cancer. In 1986, however, US researchers announced that it would begin to be trialled as a potential antiviral medication for HIV. This was the first clinical therapy to be developed for HIV. Before this, the only available treatment had been for AIDS-related conditions, such as antibiotics for infections. Nothing until this point had promised the possibility of forestalling the damage caused by HIV to the body’s immune system. People were excited about the potential for this to be a ‘miracle drug’.1 Large-scale clinical trials had been set up in the United States to test for the efficacy and safety of AZT. In 1987, the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) funded an Australian arm of the trial. It was not long after this that US trials were terminated so that people in the ‘control group’ of the trial, who had been receiving placebo pills, could be offered AZT. The drug was proving to be effective.2 This move did not, however, translate into wide availability of the drug in Australia. Australian authorities were not prepared to approve the drug on the back of US research. AZT trials continued. For those who had been diagnosed HIV positive in the 1980s, AZT was the first hope of a lifeline and, although people were cautious, there was much hype about the possibilities. -

Edit Master Title Style

Australian Senate, Occasional Lecture Series Alex Oliver Are Australians disenchanted with democracy? 7 March 2014 (Check against delivery) This week is an interesting week to be talking about democracy. There are popular uprisings in the Ukraine and Russia’s dramatic incursions into Crimea. Anti-government protests in Thailand continue. Turkey’s democratization process falters, with a deepening corruption scandal engulfing its prime minister. Cambodia’s post-election strife still simmers, with protests suppressed and human rights trampled. Egypt’s early attempts at democracy have proved an abject failure. This all sounds far removed from Australia. Geographically, of course, they are. But they are examples of democracy under fire and faltering, and that’s where Australia, incredibly, comes in. Over the next few minutes, I’m going to attempt to explain why. ------------------------ The Lowy Institute has been conducting public opinion polls on foreign policy issues for a decade, and this year we will publish our tenth annual Lowy Institute Poll. Over the years, I and former poll directors have asked hundreds of questions of Australians of all ages, from all states, and all walks of life. We’ve asked questions about the international economy, climate change, important bilateral relationships with nations like Indonesia, China, and the US, and attitudes to the rise of Asia. We’ve asked about the sorts of issues which Australians see as threats to this nation, from climate change to terrorism. Controversially, at the height of the Bush presidency in 2005, Australians ranked US foreign policy equally with Islamic fundamentalism as a threat to Australia. We’ve asked questions about Australians’ use of media in a rapidly changing media landscape, and about hotly debated issues like asylum seekers and foreign investment. -

John Howard's Federalism

John Howard, Economic Liberalism, Social Conservatism and Australian Federalism Author Hollander, Robyn Published 2008 Journal Title Australian Journal of Politics and History DOI https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8497.2008.00486.x Copyright Statement © 2008 Wiley-Blackwell Publishing. This is the author-manuscript version of this paper. Reproduced in accordance with the copyright policy of the publisher. The definitive version is available at www.interscience.wiley.com Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/22355 Link to published version http://www.wiley.com/bw/journal.asp?ref=0004-9522&site=1 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au 1 John Howard, Economic Liberalism, Social Conservatism and Australian Federalism This paper examines the way in which John Howard’s values have shaped his approach to federalism. Howard identifies himself as an economic liberal and a social conservative. and the paper traces the impact of this stance on Australian federalism. It shows how they have resulted in an increasing accretion of power to the centre and a further marginalisation of the States. The paper finds that Howard’s commitments to small government and a single market unimpeded by state borders have important consequences for federal arrangements as has his lack of sympathy with regional identity. Federalism is central to Australian political life. It is a defining institution which has shaped the nation’s political evolution.1 The founders’ conception of a nation composed of strong autonomous States, each with their own independent source of income and expansive sphere of responsibility has never been realised, if indeed it was ever intended and over time power has shifted, almost inexorably, to the centre. -

Top 10 Public Health Successes Over the Last 20 Years, PHAA Monograph Series No

PUBLIC HEALTHTOP ASSOCIATION10 OF AUSTRALIA PUBLICWorking together HEALTH for better SUCCESSES health outcomes OVER THE LAST 20 YEARS TOP 10 PUBLIC HEALTH SUCCESS FACTORS OVER THE LAST 20 YEARS 1 Join today and be part of it! Public Health Association AUSTRALIA www.phaa.net.au Great public health gains have been made in the past two decades, but efforts must continue. To maximise the benefit “of all of these success stories, persistence and vigilance are needed. Continued funding, promotion, enforcement and improvement of policies remains essential. Public Health Association of Australia, 2018 ” This report was prepared by the Public Health Association of Australia (PHAA) with specific guidance from the PHAA membership. November 2018, PHAA Monograph Series No. 2, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 AU Recommended citation: PHAA,Top 10 public health successes over the last 20 years, PHAA Monograph Series No. 2, Canberra: Public Health Association of Australia, 2018 2 CONTENTS Introduction 4 Folate: We reduced neural tube defects 6 Immunisation and eliminating disease 7 We contained the spread of HPV and its related cancers 8 Oral health: We reduced dental decay 9 Slip! Slop! Slap!: We reduced the incidence of skin cancer in young adults 10 Fewer people are dying due to smoking 11 We brought down our road death and injury toll 12 Gun control: We reduced gun deaths in Australia 13 HIV: We contained the spread 14 Finding cancer early: We prevented deaths from bowel and breast cancer 15 Discussion 16 Choosing our future 18 About the PHAA 19 TOP 10 PUBLIC HEALTH SUCCESS FACTORS OVER THE LAST 20 YEARS 3 INTRODUCTION This report highlights some of the major public health In some cases – such as immunisation and oral care success stories made in Australia in the past two decades, – treatment services to individuals are integral to the and the dramatic impact they have had on our health and measures taken.