A Unitarian in Japan – 2008.01.27 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

News Published Bythe Nichiren Shu Headquarters & Kaigai Fukyo Koenkai

Nichiren Shu News Published bythe Nichiren Shu Headquarters & Kaigai Fukyo Koenkai No. 164 February 1, 2008 1 New Year’s Greeting: ‘Let Us Chant the Odaimoku to Develop Buddha-nature’ seed in our minds? feel, even when you are By Archbishop Nichiji Sakai, Nichiren Shonin preaches in his asleep or awake, or Nichiren Shu Order letter written to Nun Myoho-ama, when you stand up or Happy New Year to you all! We “Say ‘Namu Myoho Renge Kyo’ and sit, you who practice the hope to keep our mind and body in your Buddha-nature will never fail to teaching of the Lotus good shape and to have vivid and come out.” Sutra should not stop cheerful days throughout the year. This is an important point. The chanting the sacred title, Venerable Rev. Taido Matsubara, Odaimoku, ‘Namu Myoho Renge ‘Namu Myoho Renge the President of the Namu Associa- Kyo,’ extracts the essence of the Lotus Kyo,’ at any moment. tion, who will be 101 years old this Sutra. Therefore, to chant ‘Namu By using this sacred year, says in his poem: Myoho Renge Kyo’ means to devote title as a weapon, you No matter who you are or no mat- all yourself to the Lotus Sutra, to take should chant ‘Namu ter who I am, in the essence of the Lotus Sutra. Myoho Renge Kyo,’ We are all the children of the Bud- ‘Namu Myoho Renge Kyo’ which sincerely wishing to see dha. Nichiren Shonin uttered is the assimi- the true aspect of the We all have the Enlightened One lation of himself into the title itself; in Lotus Sutra with your in our minds. -

A.C. Ohmoto-Frederick Dissertation

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of the Liberal Arts GLIMPSING LIMINALITY AND THE POETICS OF FAITH: ETHICS AND THE FANTASTIC SPIRIT A Dissertation in Comparative Literature by Ayumi Clara Ohmoto-Frederick © 2009 Ayumi Clara Ohmoto-Frederick Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2009 v The dissertation of Ayumi Clara Ohmoto-Frederick was reviewed and approved* by the following: Thomas O. Beebee Distinguished Professor of Comparative Literature and German Dissertation Advisor Chair of Committee Reiko Tachibana Associate Professor of Comparative Literature and Japanese Véronique M. Fóti Professor of Philosophy Monique Yaari Associate Professor of French Caroline D. Eckhardt Professor of Comparative Literature and English Head of the Department of Comparative Literature *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School iii Abstract This study expands the concept of reframing memory through reconciliation and revision by tracing the genealogy of a liminal supernatural entity (what I term the fantastic spirit and hereafter denote as FS) through works including Ovid’s Narcissus and Echo (AD 8), Dante Alighieri’s Vita Nuova (1292-1300), Yokomitsu Riichi’s Haru wa Basha ni notte (1915), Miyazawa Kenji’s Ginga tetsudo no yoru (1934), and James Joyce’s The Dead (1914). This comparative analysis differentiates, synthesizes, and advances upon conventional conceptions of the fantastic spirit narrative. What emerges is an understanding of how fantastic spirit narratives have developed and how their changes reflect conceptions of identity, alterity, and spirituality. Whether the afterlife is imagined as spatial relocation, transformation of consciousness, transformation of body, or hallucination, the role of the fantastic spirit is delineated by the degree to which it elicits a more profound relationship between the Self and Other. -

A Blue Cat on the Galactic Railroad: Anime and Cosmic Subjectivity

PAUL ROQUET A Blue Cat on the Galactic Railroad: Anime and Cosmic Subjectivity L OOKING UP AT THE STARS does not demand much in the way of movement: the muscles in the back of the neck contract, the head lifts. But in this simple turn from the interpersonal realm of the Earth’s surface to the expansive spread of the night sky, subjectivity undergoes a quietly radical transformation. Social identity falls away as the human body gazes into the light and darkness of its own distant past. To turn to the stars is to locate the material substrate of the self within the vast expanse of the cosmos. In the 1985 adaptation of Miyazawa Kenji’s classic Japanese children’s tale Night on the Galactic Railroad by anime studio Group TAC, this turn to look up at the Milky Way comes to serve as an alternate horizon of self- discovery for a young boy who feels ostracized at school and has difficulty making friends. The film experiments with the emergent anime aesthetics of limited animation, sound, and character design, reworking these styles for a larger cultural turn away from social identities toward what I will call cosmic subjectivity, a form of self-understanding drawn not through social frames, but by reflecting the self against the backdrop of the larger galaxy. The film’s primary audience consisted of school-age children born in the 1970s, the first generation to come of age in Japan’s post-1960s con- sumer society. Many would have first encountered Miyazawa’s Night on the Galactic Railroad (Ginga tetsudo¯ no yoru; also known by the Esperanto title Neokto de la Galaksia Fervojo) as assigned reading in elementary school. -

JBE Research Article

ISSN 1076-9005 Volume 5 1998: 241-260 Publication date: 26 June 1998 Appropriate Means as an Ethical Doctrine in the Lotus Såtra by Gene Reeves Rikkyo University [email protected] © 1998 Gene Reeves JBE Research Article Research JBE Copyright Notice Digital copies of this work may be made and distributed provided no charge is made and no alteration is made to the content. Reproduction in any other format with the exception of a single copy for private study requires the written permission of the author. All enquiries to [email protected]. Journal of Buddhist Ethics Volume 5, 1998:241-260 n this paper I claim that upàya or hben in the Lotus Såtra, con- Itrary to how it has often been translated and understood, is an ethi- cal doctrine, the central tenet of which is that one should not do what is expedient but rather what is good, the good being what will actually help someone else, which is also known as bodhisattva prac- tice. Further, the doctrine of hben is relativistic. No doctrine, teach- ing, set of words, mode of practice, etc. can claim absoluteness or finality, as all occur within and are relative to some concrete situation. But some things, doing the right thing in the right situation, can be efficacious, sufficient for salvation. As for the use of expedients in translations of upàya or hben: in the Lotus Såtra translations Hurvitz uses expedient devices, Murano expedients, and Watson expedient means. In the earlier translation from Sanskrit, Kern used skillfulness repeatedly, including in the title for the second chapter, but in a footnote he equates this with able man- agement, diplomacy, upàyakau÷alya. -

Miyazawa Kenji: Interpretation of His Literature in the Present Japan1

Asian Studies I (XVII), 2 (2013), pp. 89–104 Miyazawa Kenji: Interpretation of his Literature in the Present Japan1 Nagisa MORITOKI ŠKOF* Abstract This paper seeks an answer to the question of why Kenji Miyazawa is attracting people’s attention now more than ever, with particular focus on Miyazawa’s view on Buddhism and nature, as expressed in his literature, by considering its value in contemporary Japan. This paper takes three features as examples: “the true happiness”, changing phenomena, and interaction between human beings and nature; and it concludes that Miyazawa’s messages support people in present-day Japan and assure them that they are on the right path in the long flow of the universe’s historical timeline. Keywords: Buddhism, nature, literature, Japan, interaction Izvleček Članek poskuša najti odgovor na vprašanje, zakaj je delo Kenjija Miyazawe še vedno priljubljeno na Japonskem, danes bolj kot kadarkoli, članek osredotoča na Miyazawov pogled na budizem in naravo, kakor se odražata v njegovi književnosti, in poskuša oceniti njen pomen v sodobni Japonski. Za primer si vzame tri značilnosti iz njegovih del: »resnično srečo«, vedno spreminjajoče se pojave in medsebojni odnos med človekom in naravo, ter zaključi, da sporočilnost Miyazawovega dela nudi oporo ljudem na Japonskem tudi v današnjem času in jim zagotavlja, da je pot, po kateri grejo, pravilna pot znotraj dolgega toka vesoljske zgodovine. Ključne besede: Budizem, narava, literatura, Japonska, medsebojno vplivanje 1 This article is based on these two lectures about MIYAZAWA Kenji on “Teden UL” (Open day of the University of Ljubljana), December 6, 2012 and “Pozor, Znanje na Cesti!” (Warning, Knowledge is on the street!), December 19, 2012. -

2015Year Faculty of Education Year Faculty/Graduate School

Faculty/Graduate Year 2015Year Faculty of Education School Lecture Code CC334505 Subject Specialized Education Subject Name 日本の近現代文学 Subject Name ニホンノキンゲンダイブンガク (Katakana) Subject Name Modern and Contemporary Japanese Literature in English Instructor NISHIHARA DAISUKE Instructor ニシハラ ダイスケ (Katakana) Instructor's Office Faculty of Education A310 Extension Number 6877 E-mail Address [email protected] Campus HigashiHiroshima Semester 3Year First Semester Tuesday Period Day and Period Classroom Number 5,Period 6 Lesson Style Lesson Style Lecture Lecture (More Details) Language of Credits 2 Class Hours/Week 2 J:Japanese Instruction Although this class is mainly for students in the “Course in Teaching Japanese as a Second Language,” participation by Eligible Students students from other courses and other faculties is truly welcomed. Course Level 3:Undergraduate High-Intermediate Course Area(Area) 04:Humanities Course Area(Discipline) 04:Literature Keywords Reading poems from the Meiji Era and the Taisho Era Special Subject for Special Subject Teacher Education Class Status within Subject relating to Japanese culture in the program Educational Program 日本語教育プログラム Criterion referenced (知的能力・技能) Evaluation ・日本語教育6領域に関して個別的・専門的に研究する Class Objectives/Class In this class, students will read 76 excellent Japanese poems from the Meiji Era and the Taisho Era. Outline lesson1:Introduction lesson2:Shintaishisho lesson3:Kyukin Susukida・Ariake Kanbara lesson4:Toson Shimazaki lesson5:Bansui Doi lesson6:Bin Ueda lesson7:Hakushu Kitahara lesson8:Kafu Nagai lesson9:Takuboku Ishikawa Class Schedule lesson10:Kotaro Takamura lesson11:Sakutaro Hagiwara lesson12:Saisei Murou lesson13:Haruo Sato lesson14:Kenji Miyazawa lesson15:Review Two types of assignments will be given: 1) Copying the poems in the texts by hand and submitting the copy; and 2) submitting a term-end report Text/Reference Books, Documents will be handed out in class. -

Miyazawa Kenji: the Poet As Asura?

Volume 5 | Issue 9 | Article ID 2526 | Sep 03, 2007 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus Miyazawa Kenji: The Poet as Asura? Hiroaki Sato Miyazawa Kenji: The Poet as Asura? Hiroaki SATO Do they still require schoolchildren to memorize Miyazawa Kenji’s poem Ame ni mo makezu? I ask my young friend Donald Howard who is teaching English in Iwate, where his wife Saori is from. Donald and Saori had also visited the Miyazawa Memorial Museum for me a few years earlier, when they still lived in New York, and brought back a CD of Kenji’s musical compositions orchestrated and sung. After Hanamaki checking with a couple of teachers, Donald responds: Yes, they do. Nonetheless, when I had the first opportunity to translate a group of Kenji’s poems into I asked because, though I myself do not English for publication, the translations later remember ever being required to memorize the gathered in Spring & Asura: Poems of Kenji poem in school during the 1950s, I’ve learned Miyazawa (Chicago Review Press, 1973), I did the requirement was in force in some places, at not include Ame ni mo makezu in my selection. various times. And if it still is, it must be in Why? I’ve since wondered, from time to time. Iwate, I thought, where Kenji was born, in 1896, grew up, spent most of his life, and died, Was I intimidated by its fame? Or was I put off in 1933. I learned, years ago, itsby it? Or, finding myself in New York in the last extracurricular popularity, as it were: itphase of the Hippie Era, did I decide that the appears on all sorts of souvenirs – towels, kind of sentiment expressed in the poem was mugs, fans, etc. -

KENJI MIYAZAWA׳S NIGHT on the GALACTIC RAILROAD Is a March

KENJI MIYAZAWA’S NIGHT ON THE GALACTIC RAILROAD is a March, 2016 dvd upgrade, now available to borrow from the Hugh Stouppe Memorial Library of the Heritage United Methodist Church of Ligonier, Pennsylvania. Below is Kino Ken’s review of it. 16 of a possible 20 points **** of a possible ***** Japan 1985 color 107 minutes English-dubbed version of a feature animation fantasy Asahi Shimbun / Asahi National Broadcasting Co. Ltd. / Nippon Herald Films Producers: Masato Hara, Atsumi Tashiro Key: *indicates outstanding technical achievement or performance Points: Direction: Gisaburô Sugii English-Language Direction: Arlen Tarlofsky 1 Editing 2 Cinematography: Yasuo Maeda* 1 Lighting 2 Writing: Minoru Betsuyaku from an idea by Hiroshi Masumara, based on a novel by Kenji Miyazawa 2 Animation Direction: Marisuke Eguchi Animators: Marisuke Eguchi, Nobuko Abe, Makiko Futaki, Kazuyuki Kobayashi, Yasunari Maeda, Sayuri Matsumoto, Kaoru Nakajima, Yasuhiro Nakura, Hidekazu Ohara, Yutaka Oka, Takaya Ono, Michiyo Sakurai, Yukiya Senda, Tamotsu Tanaka, Tsukasa Tannai, Takamitsu Yukawa, Kazushige Yusa 2 Music: Haruomi Hosono (Yellow Magic Orchestra member) 2 Art Direction: Mihoko Magoori* Character Design: Takao Kodama Stage Design: Minoru Aoki* 2 Sound 0 English Voices Cast Acting 2 Creativity 16 total points English-Language Voices Cast: Amy Birnbaum (Tadashi), Scott Cargle (Conductor), Crispin Freeman (Campanella), Tatsuyuki Jinnai (Campanella’s Father), Rachael Lillis (Marceau / Dairy Woman), Eric Moo (Wireless Operator), Lisa Ortiz (Kaoru), Scott Rayow (Dairy Man), Sam Riegel (Young Man), Ryuji Saikachi (Store Owner), Eric Schussler (Father), Eric Stuart (Lighthouse Keeper), Veronica Taylor (Giovanni), Greg Wolfe (Teacher / Scientist), Oliver Wyman (Zanelli, heron catcher) NIGHT ON THE GALACTIC RAILROAD concerns that most fearsome of phantoms, death. -

ANALYSIS of LEXICON in JAPANESE ADULT and CHILDREN’S LITERATURE Comparison of Kawauso and Serohiki No Gauche

INSTITUTIONEN FÖR SPRÅK OCH LITTERATURER ANALYSIS OF LEXICON IN JAPANESE ADULT AND CHILDREN’S LITERATURE Comparison of Kawauso and Serohiki no Gauche Mimmi Widestrand Uppsats/Examensarbete: 15 hp Program och/eller kurs: Japanska Nivå: Grundnivå Termin/år: Vt/2016 Handledare: Yasuko Nagano-Madsen Examinator: Martin Nordeborg Rapport nr: xx (ifylles ej av studenten/studenterna) 1 Abstract Uppsats/Examensarbete: 15hp Program och/eller kurs: Japanska Nivå: Grundnivå Termin/år: Vt/2016 Handledare: Yasuko Nagano-Madsen Examinator: Martin Nordeborg Rapport nr: xx (ifylles ej av studenten/studenterna Japanese vocabulary, native Japanese words, Sino- Japanese words, Nyckelord: foreign loan words, onomatopoeia, Mukōda, Miyazawa This paper investigates the usage of Japanese vocabulary in two different texts: Kawauso (The Otter) by Kuniko Mukōda and Serohiki no Gauche (Gauche the cellist) by Kenji Miyazawa. Japanese vocabulary is commonly divided into three main lexical classes: Native Japanese words (NJ, 和語), Sino-Japanese Words (SJ, 漢語) and foreign loan words (FL, 外来語). In addition, many scholars consider onomatopoeia as a fourth lexical class. It has therefore been considered as such in this study. The framework for this study is based on the work of Yamaguchi (2007) and the frequency of appearance of the four lexical classes in each of the texts is measured and compared between each other. The results show that with respect to the total number of words in each respective text, Mukōda more frequently used NJ, SJ than Miyazawa while FL was used more frequently by Miyazawa. Both authors however used many hybrid words, which were not included in this study. Nonetheless, when comparing the number of appearance of NJ, SJ and FL with respect to the appearance of those three categories in the texts, the results show very similar results between both texts. -

Proper Names in Translational Contexts

ISSN 1799-2591 Theory and Practice in Language Studies, Vol. 6, No. 1, pp. 1-10, January 2016 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17507/tpls.0601.01 Proper Names in Translational Contexts Eriko Sato Department of Asian and Asian American Studies, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, New York, USA Abstract—Rendering of proper names in translational contexts may be a simple and automatic procedure that only involves minor sound adjustments. However, translators take, and sometimes have to adopt, all kinds of strategies with proper names, especially in fictional texts, where names almost always carry auctorial meanings that implicitly support the theme of the story. Names, in fact, bear a variety of connotative meanings and also serve as cultural identifiers of texts. Accordingly, rendering of names in translational contexts often has to deal with many issues such as their phonological, orthographical, morpho-semantic, and pragmatic idiosyncrasies, their accessibility to the target language readers, and their socio-political implications. Following the framework of descriptive translation studies, this paper first examines some English translations of Japanese literary texts from primary and secondary sources, and then provides a qualitative analysis of English translations of a novel by Kenji Miyazawa (1896-1933), Ginga Tetsudō no Yoru (Night of the Milky Way Railway), focusing on proper names. The latter novel is filled with fictional and non-fictional names whose cultural identities are deliberately made unclear or paradoxical to support the theme of the novel. The analysis provided in this paper empirically shows that translation of proper names plays a pivotal role for sustaining the cultural orientation of the text and the theme of the story. -

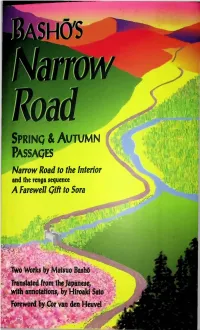

Spring &Autumn

Spring & Autumn Passages Narrow Road to the Interior and the renga sequence A Farewell Qift to Sora iV-y, . p^: Two Works by Matsuo BasM Translated from the Japanese, with annotations, by Hiroaki Sato Foreword by Cor van den Heuvel '-f BASHO'S NARROW ROAD i j i ; ! ! : : ! I THE ROCK SPRING COLLECTION OF JAPANESE LITERATURE ; BaSHO'S Narrow Road SPRINQ & AUTUMN PASSAQES Narrow Road to the Interior AND THE RENGA SEQUENCE A Farewell Gift to Sora TWO WORKS BY MATSUO BASHO TRANSLATED FROM THE JAPANESE, WITH ANNOTATIONS, BY Hiroaki Sato FOREWORD BY Cor van den Heuvel STONE BRIDGE PRESS • Berkeley,, California Published by Stone Bridge Press, P.O, Box 8208, Berkeley, CA 94707 510-524-8732 • [email protected] • www.stoncbridgc.com Cover design by Linda Thurston. Text design by Peter Goodman. Text copyright © 1996 by Hiroaki Sato. Signature of the author on front part-title page: “Basho.” Illustrations by Yosa Buson reproduced by permission of Itsuo Museum. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher. Printed in the United States of America 10 987654321 LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOG1NG-1N-PUBL1 CATION DATA Matsuo, BashO, 1644-1694. [Oku no hosomichi. English] Basho’s Narrow road: spring and autumn passages: two works / by Matsuo Basho: translated from the Japanese, with annotations by Hiroaki Sato. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. Contents: Narrow road to the interior and the renga sequence—A farewell gift to Sora. ISBN 1-880656-20-5 (pbk.) 1- Matsuo, Basho, 1644-1694—Journeys—Japan. -

Home to the Dreamer: Kenji Miyazawa and Hanamaki City

Feature Sharing Japanese Literature with the World Home to the Dreamer: Kenji Miyazawa and Hanamaki City YOKO KOIZUMI Three hours by bullet train from Tokyo Station, Hanamaki City is known as the place where one of Japan’s most prominent and prolific Japanese authors, Kenji Miyazawa, was born and lived. Unsung in his short lifetime, the highly intellectual writer left behind a legacy of imaginative worlds that have enchanted readers for decades. 1 INGA Tetsudo no Yoru (Night on the Galactic poems, and also wrote tanka poems, plays, song Railroad), Chuumon no Ooi Ryouriten (The lyrics and more. He wrote such an enormous number GRestaurant of Many Orders), Sero Hiki no of tanka that many are not well-known.” Goshu (Gauche the Cellist), Yodaka no Hoshi (The Miyazawa’s erudition was the foundation of this Nighthawk Star)—most Japanese people can name immense body of work. He was knowledgeable about these Kenji Miyazawa literary works, many of which various fields and quick to pounce on the latest in are read in elementary schools. world news. “Night on the Galactic Railroad, for During his lifetime, however, Miyazawa was example, has a scene about people who died on the an unknown who wrote his fiction while working Titanic. Although he lived in a remote region, he had a day job. From 1921, Miyazawa was a teacher at a tremendously sensitive antenna for world events,” Hanamaki Agricultural School (currently Iwate notes the curator. Prefectural Hanamaki Agricultural High School) The Miyazawa Kenji Museum divides its exhibits for six years from the age of twenty-five.