A Management Guide to Software Maintenance in COTS-Based Systems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ASSESSING the MAINTAINABILITY of C++ SOURCE CODE by MARIUS SUNDBAKKEN a Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requireme

ASSESSING THE MAINTAINABILITY OF C++ SOURCE CODE By MARIUS SUNDBAKKEN A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Computer Science WASHINGTON STATE UNIVERSITY School of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science DECEMBER 2001 To the Faculty of Washington State University: The members of the Committee appointed to examine the thesis of MARIUS SUNDBAKKEN find it satisfactory and recommend that it be accepted. Chair ii ASSESSING THE MAINTAINABILITY OF C++ SOURCE CODE Abstract by Marius Sundbakken, M.S. Washington State University December 2001 Chair: David Bakken Maintenance refers to the modifications made to software systems after their first release. It is not possible to develop a significant software system that does not need maintenance because change, and hence maintenance, is an inherent characteristic of software systems. It has been estimated that it costs 80% more to maintain software than to develop it. Clearly, maintenance is the major expense in the lifetime of a software product. Predicting the maintenance effort is therefore vital for cost-effective design and development. Automated techniques that can quantify the maintainability of object- oriented designs would be very useful. Models based on metrics for object-oriented source code are necessary to assess software quality and predict engineering effort. This thesis will look at C++, one of the most widely used object-oriented programming languages in academia and industry today. Metrics based models that assess the maintainability of the source code using object-oriented software metrics are developed. iii Table of Contents 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................1 1.1. Maintenance and Maintainability....................................................................... -

Software Maintenance Maintenance Is Inevitable Types of Maintenance

SoftWindows 8/18/2003 Software Maintenance • Managing the processes of system change Reverse Engineering (Software Maintenance & Reengineering) © SERG Maintenance is Inevitable • The system requirements are likely to change while the system is being developed because the environment is changing. • When a system is installed in an environment it changes that environment and therefore changes the system requirements. Reverse Engineering (Software Maintenance & Reengineering) © SERG Types of Maintenance • Perfective maintenance – Changing a system to make it meet its requirements more effectively. • Adaptive maintenance – Changing a system to meet new requirements. • Corrective maintenance – Changing a system to correct deficiencies in the way meets its requirements. Reverse Engineering (Software Maintenance & Reengineering) © SERG Distributed Objects 1 SoftWindows 8/18/2003 Distribution of Maintenance Effort Corrective maintenance (17%) Adaptive maintenance Perfective (18%) maintenance (65%) Reverse Engineering (Software Maintenance & Reengineering) © SERG Evolving Systems • It is usually more expensive to add functionality after a system has been developed rather than design this into the system: – Maintenance staff are often inexperienced and unfamiliar with the application domain. – Programs may be poorly structured and hard to understand. – Changes may introduce new faults as the complexity of the system makes impact assessment difficult. – The structure may be degraded due to continual change. – There may be no documentation available to describe the program. Reverse Engineering (Software Maintenance & Reengineering) © SERG The Maintenance Process • Maintenance is triggered by change requests from customers or marketing requirements. • Changes are normally batched and implemented in a new release of the system. • Programs sometimes need to be repaired without a complete process iteration but this is dangerous as it leads to documentation and programs getting out of step. -

System Software Maintenance and Support 24X7

SYSTEM SOFTWARE MAINTENANCE AND SUPPORT SERVICES - PREMIUM These Premium System Software Maintenance and Support Service terms and conditions (“Terms and Conditions”) apply to any quote, order, order acknowledgment, and invoice, and any sale or provision of Premium System Software Maintenance and Support Services as defined herein provided to Customer by Viavi Solutions Inc. (“Viavi”), in addition to Viavi’s General Terms (“General Terms”) and/or Software License Terms, which are incorporated by reference herein and are either attached hereto, available at www.viavisolutions.com/terms or available upon request. k) Severity Level means classification of a problem determined by Viavi personnel 1. PURPOSE AND SCOPE based upon the Customer’s assessment of business impact. The three (3) Severity Levels that apply to the Services are as follows: These Terms and Conditions describe the Services that Viavi will provide to, and perform for, Customer. These Terms and Conditions apply to Services for standard Software, as 1) Problem Report – Critical means conditions that severely affect the defined herein, and are limited to the System configuration specified in a Statement of primary functionality of the System and because of the business impact to the Work (“SOW”) or other ordering document (i.e., a quote, order, order acknowledgment customer requires non-stop immediate corrective action, regardless of time of day or invoice) which contains a description of the System. All Services and Documentation or day of the week as viewed by a customer -

Software Engineering Software Maintenance

SOFTWARE ENGINEERING SOFTWARE MAINTENANCE Software maintenance is the process of modification or making changes in the system after delivery to overcome errors and faults in the system that were not uncovered during the early stages of the development cycle. LEARNING OBJECTIVES • To study on why maintenance is an issue. • To study on reverse engineering and limitations. • To organize data. • To check what the system does. SOFTWARE MAINTENANCE The IEEE Standard for Software Maintenance (IEEE 1219) gave the definition for software maintenance as “The process of modifying a software system or component after delivery to correct faults, improves performance or other attributes, or adapt to a changed environment.” Maintenance Principles 100 Hardware Development 60 Software 20 Maintenance Percent of total cost total of Percent 1995 2000 2010 The IEEE/EIA 12207 Standard defines maintenance as modification to code and associated documentation due to a problem or the need for improvement. Nature of Maintenance Modification requests are logged and tracked, the impact of proposed changes are determined, code and other software artifacts are modified, testing is conducted, and a new version of the software product is released. Maintainers can learn from the developer´s knowledge of the software. Need for Maintenance Maintenance must be performed in order to: • Correct faults. • Improve the design. • Implement enhancements. • Interface with other systems. • Adapt programs so that different hardware, software, system features, and telecommunications facilities can be used. • Migrate legacy software. • Retire software Tasks of a maintainer The maintainer does the following functions: • Maintain control over the software´s day-to-day functions. • Maintain control over software modification. -

Read Ms. Shaw's First Amended Complaint

Janet L. Goldstein Peter W. Chatfield THE MARTYN FIRM, PLLC PHILLIPS & COHEN LLP 1054 31st Street, NW 2000 Massachusetts Ave., NW Washington, D.C. 20007 Washington, D.C. 20036 Tel: (202) 965-3060 Tel: (202) 833-4567 Fax: (202) 965-3063 Fax: (202) 833-1815 Jonathan A. Willens (JW-9180) JONATHAN A. WILLENS LLC 217 Broadway, Suite 707 New York, New York 10007 Tel: (212) 619-3749 Fax: (800) 879-7938 Attorneys for qui tam plaintiff Ann-Marie Shaw UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ) 06 CV 3552 (DLI) (SMG) ex rel. ANN-MARIE SHAW ) and ) AMENDED COMPLAINT ) FOR VIOLATIONS OF STATE OF CALIFORNIA ex rel.ANN-MARIE SHAW ) FEDERAL AND STATE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA ex rel.ANN-MARIE SHAW ) FALSE CLAIMS ACTS STATE OF FLORIDA ex rel.ANN-MARIE SHAW ) STATE OF HAWAII ex rel.ANN-MARIE SHAW ) STATE OF ILLINOIS ex rel.ANN-MARIE SHAW ) COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS ) ex rel.ANN-MARIE SHAW ) STATE OF NEVADA ex rel.ANN-MARIE SHAW ) COMMONWEALTH OF VIRGINA ) ex rel.ANN-MARIE SHAW ) STATE & CITY OF NEW YORK ) ex rel.ANN-MARIE SHAW, ) ) JURY TRIAL DEMANDED Plaintiffs, ) ) FILED UNDER SEAL v. ) ) CA, INC., ) ) Defendant. ) _______________________________________________ ) Through her attorneys, plaintiff and qui tam relator Ann-Marie Shaw, for her Amended Complaint against Defendant CA, Inc. (“CA”), formerly known as Computer Associates International, Inc. or “Computer Associates,” alleges as follows: FACTS COMMON TO ALL COUNTS A. Introduction 1. This is a civil action to recover damages and civil penalties arising from false and/or fraudulent statements, records, and claims made and caused to be made by the Defendant CA and/or its agents and employees in violation of the Federal Civil False Claims Act, 31 U.S.C. -

Techniques for Software Maintenance 57 02 58

01 Techniques for Software Maintenance 57 02 58 03 59 04 60 Kostas Kontogiannis 05 61 Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, National Technical University of Athens, 06 62 Athens, Greece 07 63 08 64 09 65 10 66 Abstract 11 Software maintenance constitutes a major phase of the software life cycle. Studies indicate that software 67 12 maintenance is responsible for a significant percentage of a system’s overall cost and effort. The software 68 13 engineering community has identified four major types of software maintenance, namely, corrective, 69 14 perfective, adaptive, and preventive maintenance. Software maintenance can be seen from two major points 70 15 of view. First, the classic view where software maintenance provides the necessary theories, techniques, 71 16 methodologies, and tools for keeping software systems operational once they have been deployed to their 72 17 operational environment. Most legacy systems subscribe to this view of software maintenance. The second 73 18 view is a more modern emerging view, where maintenance is an integral part of the software development 74 19 process and it should be applied from the early stages in the software life cycle. Regardless of the view by 75 which we consider software maintenance, the fact is that it is the driving force behind software evolution, a 20 76 very important aspect of a software system. This entry provides an in-depth discussion of software 21 77 Q1 maintenance techniques, methodologies, tools, and emerging trends. 22 78 23 79 24 80 25 INTRODUCTION type of software maintenance is referred to as Adaptive 81 26 82 Software Maintenance and refers to activities that aim to 27 83 Software maintenance is an integral part of the software modify models and artifacts of existing systems so that 28 84 life cycle and has been identified as an activity that affects these systems can be integrated with new systems or 29 85 in a major way the overall system cost and effort. -

Empirical Studies Concerning the Maintenance of UML Diagrams and Their Use in the Maintenance of Code: a Systematic Mapping Study ⇑ Ana M

Information and Software Technology 55 (2013) 1119–1142 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Information and Software Technology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/infsof Empirical studies concerning the maintenance of UML diagrams and their use in the maintenance of code: A systematic mapping study ⇑ Ana M. Fernández-Sáez a,c, , Marcela Genero b, Michel R.V. Chaudron c,d a Alarcos Quality Center, University of Castilla-La Mancha, Spain b ALARCOS Research Group, Department of Technologies and Information Systems, University of Castilla-La Mancha, Spain c Leiden Institute of Advanced Computer Science, LeidenUniversity, The Netherlands d Joint Computer Science and Engineering Department of Chalmers University of Technology and University of Gothenburg, SE-412 96 Gõteborg, Sweden article info abstract Article history: Context: The Unified Modelling Language (UML) has, after ten years, become established as the de facto Received 1 December 2011 standard for the modelling of object-oriented software systems. It is therefore relevant to investigate Received in revised form 12 December 2012 whether its use is important as regards the costs involved in its implantation in industry being worth- Accepted 14 December 2012 while. Available online 4 February 2013 Method: We have carried out a systematic mapping study to collect the empirical studies published in order to discover ‘‘What is the current existing empirical evidence with regard to the use of UML dia- Keywords: grams in source code maintenance and the maintenance of the UML diagrams themselves? UML Results: We found 38 papers, which contained 63 experiments and 3 case studies. Empirical studies Software maintenance Conclusion: Although there is common belief that the use of UML is beneficial for source code mainte- Systematic mapping study nance, since the quality of the modifications is greater when UML diagrams are available, only 3 papers Systematic literature review concerning this issue have been published. -

Constructing a Shared Infrastructure for Software Architecture Analysis and Maintenance

Constructing a Shared Infrastructure for Software Architecture Analysis and Maintenance Joshua Garcia? , Mehdi Mirakhorliy , Lu Xiaoα , Yutong Zhaoα , Ibrahim Mujhidy , Khoi Phamβ , Ahmet Okutany , Sam Malek? , Rick Kazmanγ , Yuanfang Caiδ , and Nenad Medvidovic´β ? University of California Irvine, fjoshug4,[email protected] y Rochester Institute of Technology, fmxmvse,ijm9654,[email protected] α Stevens Institute of Technology, flxiao6,[email protected] β University of Southern California, fkhoipam,[email protected] γ University of Hawaii, [email protected] δ Drexel University, [email protected] Abstract—Over the past three decades software engineering problem, and engineers are forced to guess—and they very researchers have produced a wide range of techniques and tools often actually ignore—the architectural implications of their for understanding the architectures of large, complex systems. choices and decisions. However, these have tended to be one-off research projects, and their idiosyncratic natures have hampered research collaboration, To overcome this problem, for over the past two decades, extension and combination of the tools, and technology transfer. software architecture research has yielded many different tools The area of software architecture is rich with disjoint research and techniques [9]. However, empirical studies and technology and development infrastructures, and datasets that are either pro- prietary or captured in proprietary formats. This paper describes transfer are impeded by disjoint research and development a concerted effort to reverse these trends. We have designed and environments, lack of a shared infrastructure, high initial costs implemented a flexible and extensible infrastructure (SAIN) with associated with developing and/or integrating robust tools, and the goal of sharing, replicating, and advancing software architec- a dearth of datasets. -

Software Maintenance Costs

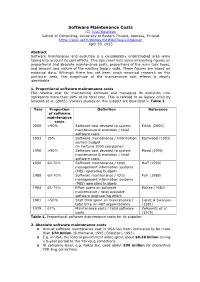

Software Maintenance Costs (C) Jussi Koskinen School of Computing, University of Eastern Finland, Joensuu, Finland https://wiki.uef.fi/display/tktWiki/Jussi+Koskinen April 30, 2015 Abstract Software maintenance and evolution is a considerably understudied area while taking into account its cost effects. This document lists some interesting figures on proportional and absolute maintenance costs, proportions of the main task types, and amount and nature of the existing legacy code. These figures are based on empirical data. Although there has not been much empirical research on this particular area, the magnitude of the maintenance cost effects is clearly identifiable. 1. Proportional software maintenance costs The relative cost for maintaining software and managing its evolution now represents more than 90% of its total cost. This is refered to as legacy crisis by Seacord et al. (2003). Various studies on this subject are described in Table 1. Year Proportion Definition Reference of software maintenance costs 2000 >90% Software cost devoted to system Erlikh (2000) maintenance & evolution / total software costs 1993 75% Software maintenance / information Eastwood (1993) system budget (in Fortune 1000 companies) 1990 >90% Software cost devoted to system Moad (1990) maintenance & evolution / total software costs 1990 60-70% Software maintenance / total Huff (1990) management information systems (MIS) operating budgets 1988 60-70% Software maintenance / total Port (1988) management information systems (MIS) operating budgets 1984 65-75% Effort spent on software McKee (1984) maintenance / total available software engineering effort. 1981 >50% Staff time spent on maintenance / Lientz & Swanson total time (in 487 organizations) (1981) 1979 67% Maintenance costs / total software Zelkowitz et al. -

How to Save on Software Maintenance Costs an Omnext White Paper on Software Quality

How to save on software maintenance costs An Omnext white paper on software quality November 2014 © 2014 Omnext BV All rights reserved. No part of the contents of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior written permission of Omnext BV. Trademarked names may appear in this document. Rather than use a trademark symbol with every occurrence of a trademarked name, we use the names only in an editorial fashion and to the benefit of the trademark owners, with no intention of infringement of the trademark. Postbus 114, 3900 AC Veenendaal Koningsschot 45, Veenendaal The Netherlands Tel. +31 (0) 318 592 322 Omnext white paper How to save on software maintenance costs Abstract The cost of software maintenance is rising dramatically and it has been estimated in [1] that nowadays software maintenance accounts for more than 90% of the total cost of software, whereas it was around 50% a couple of decades ago. There are several reasons for this. We can see that software systems become hard to maintain over time, while every day more and more software is being produced. Documentation is lacking or incomplete and the people who know the software leave or retire without being replaced. Furthermore, systems tend to become increasingly complex. This makes extending a system difficult and costly. Rebuilding a system is usually not an option because the system that needs to be replaced is large, the test coverage unknown and the original and modified requirements are not well documented. Figure 1: Development of Software maintenance costs as percentage of total cost Given the enormous costs and efforts involved in software maintenance, every company should consider ways to make savings here, as also observed in [15]. -

Software Reengineering: Technology a Case Study and Lessons Learned U.S

Computer Systems Software Reengineering: Technology A Case Study and Lessons Learned U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE National Institute of Mary K. Ruhl and Mary T. Gunn Standards and Technology NIST NIST i PUBUCATiONS 100 500-193 1991 V DATE DUE '11// fr . — >^c"n.u, jnc. i(8-293 ~ 1— NIST Special Publication 500-193 Software Reengineering: A Case Study and Lessons Learned Mary K. Ruhl and Mary T. Gunn Computer Systems Laboratory National Institute of Standards and Technology Gaithersburg, MD 20899 September 1991 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE Robert A. Mosbacher, Secretary NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF STANDARDS AND TECHNOLOGY John W. Lyons, Director Reports on Computer Systems Technology The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) has a unique responsibility for computer systems technology within the Federal government. NIST's Computer Systems Laboratory (CSL) devel- ops standards and guidelines, provides technical assistance, and conducts research for computers and related telecommunications systems to achieve more effective utilization of Federal information technol- ogy resources. CSL's responsibilities include development of technical, management, physical, and ad- ministrative standards and guidelines for the cost-effective security and privacy of sensitive unclassified information processed in Federal computers. CSL assists agencies in developing security plans and in improving computer security awareness training. This Special Publication 500 series reports CSL re- search and guidelines to Federal agencies as well as to organizations in industry, government, and academia. National Institute of Standards and Technology Special Publication 500-193 Natl. Inst. Stand. Technol. Spec. Publ. 500-193, 39 pages (Sept. 1991) CODEN: NSPUE2 U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON: 1991 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. -

Partially Automated In-Line Documentation (PAID): Design and Implementation of a Software Maintenance Tool

Partially Automated In-Line Documentation (PAID): Design and Implementation of a Software Maintenance Tool Jane E. Huffman Clifford G. Burgess Science Applications University of Southem International Carporation Mississippi Technical documentation refers to information on the ABSTRACT various phases of the software life cycle. It includes design specifications, performance specifications, Large scale budget and schedule overruns of software functional specifications, development information, etc. projects have sparked interest in software maintenance. This documentation is usually Written by the system The importance of accurate technical documentation to designers or programmers. It is found in-line in the the maintenance pmcess is presented. A possible solution source program, on-line,or in had copy form. It is often to the lack of adequate technical documentation is used as referem material for maintenance of a suggested -- a partially automated in-line documentation progradsystem. system. This system uses software merrics to determine where comments should be placed in source programs. Unfortumely, quite often no technical documentation The system can be used as a tool in software development is produced.. In addition, when documentation is and/or softwm maintenance. produced, it IS often poorly or incompletely Written, and may not be kept current. These factors contribute to the KEY WORDS: Software Engineering difficulty of maintaining the software at a later time. Software Maintenance Software Tools Software Metrics Documentation In-Line Documentation 2. RESEARCH RATIONALE This paper will show that undocumented (or poorly documented) source code can be documented with the 1. INTRODUCTION help of a partially automated in-line documentation system, PAID. This system seeks to improve software maintenance by facilitating the in-line documentation of Large budget and schedule overruns on many software programs.