Historic Core Appraisal 2016 Chapter 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Delegates' Pre-Symposium Information Pack

2016 Joint BES and CCI Annual Symposium Making a Difference in Conservation: Improving the Links between Ecological Research, Policy and Practice 11 – 13 April 2016 David Attenborough Building, Cambridge Pembroke St, Cambridge CB2 3QY http://www.conservation.cam.ac.uk/ Delegates’ Pre-symposium Information Pack #BEScci Cambridge Cambridge is a university city and the county town of Cambridgeshire, England, on the River Cam about 50 miles (80 km) north of London. At the United Kingdom Census 2011, its population was 123,867, including 24,488 students. There is archaeological evidence of settlement in the area in the Bronze Age and in Roman Britain; under Viking rule, Cambridge became an important trading centre. The first town charters were granted in the 12th century, although city status was not conferred until 1951. Cambridge is the home of the University of Cambridge, founded in 1209 and one of the top five universities in the world. The university includes the Cavendish Laboratory, King's College Chapel, and the Cambridge University Library. The Cambridge skyline is dominated by the last two buildings, along with the spire of the Our Lady and the English Martyrs Church, the chimney of Addenbrooke's Hospital and St John's College Chapel tower. Cambridge is at the heart of the high-technology Silicon Fen with industries such as software and bioscience and many start-up companies spun out of the university. Over 40% of the workforce have a higher education qualification, more than twice the national average. Cambridge is also home to the Cambridge Biomedical Campus, one of the largest biomedical research clusters in the world, soon to be home to AstraZeneca, a hotel and relocated Papworth Hospital. -

Fuller's Hill Cottages Access Statement

Fuller’s Hill Cottages Access Statement CONTENTS: Contents page 2 Introduction 3 Accommodation: The Stables, The Tack Room & Garden 4 Useful, local telephone numbers 9 Local pubic transport 10 Visiting Cambridge 11 Parking in Cambridge 12 Other useful contacts 15 Restaurants, pubs and bars in Cambridge 19 Churches 33 Cinemas 37 Concert venues 40 Guided Tours 48 Museums & galleries in Cambridge 50 Parks & gardens 62 Places of interest outside Cambridge 65 Shopping in Cambridge 75 Sports centres 82 Theatres 85 Transport in Cambridge 91 University Colleges 94 For more information… 105 2 FULLER’S HILL COTTAGES’ ACCESS STATEMENT Fuller’s Hill Cottages is a large converted 1840 barn, made into four, luxury cottages, which were opened in 2012. Two of our cottages are disabled accessible; The Stables and The Tack Room. We have tried to provide as much information as possible in this statement but if you have any queries please do call Jenny Jefferies on 07544 208959. We look forward to welcoming you. Pre – Arrival Bookings/enquiries can be made via either website or by direct telephone to Jenny on 07544 208959. It is possible to do your grocery shopping through www.tesco.com or www.asda.co.uk or www.Sainsburys.co.uk. Delivery should be made after your arrival time. Alternatively we can arrange for a deluxe or standard breakfast hamper to be in your cottage for your arrival. We can also arrange for a personalised Supper Box to be delivered - please contact Jenny for further details. Arrival & Car Parking Facilities You may park your car directly in front of each apartment The Car Park is level and pebble-dashed, with space for around 12 cars The Car Park lighting at night is by remote sensors that come on automatically. -

The David Attenborough Building Pembroke St, Cambridge CB2 3QY

Venue The David Attenborough Building Pembroke St, Cambridge CB2 3QY http://www.conservation.cam.ac.uk/ Cambridge Cambridge is a university city and the county town of Cambridgeshire, England, on the River Cam about 50 miles (80 km) north of London. At the United Kingdom Census 2011, its population was 123,867, including 24,488 students. There is archaeological evidence of settlement in the area in the Bronze Age and in Roman Britain; under Viking rule, Cambridge became an important trading centre. The first town charters were granted in the 12th century, although city status was not conferred until 1951. Cambridge is the home of the University of Cambridge, founded in 1209 and one of the top five universities in the world. The university includes the Cavendish Laboratory, King's College Chapel, and the Cambridge University Library. The Cambridge skyline is dominated by the last two buildings, along with the spire of the Our Lady and the English Martyrs Church, the chimney of Addenbrooke's Hospital and St John's College Chapel tower. Cambridge is at the heart of the high-technology Silicon Fen with industries such as software and bioscience and many start-up companies spun out of the university. Over 40% of the workforce have a higher education qualification, more than twice the national average. Cambridge is also home to the Cambridge Biomedical Campus, one of the largest biomedical research clusters in the world, soon to be home to AstraZeneca, a hotel and relocated Papworth Hospital. Parker's Piece hosted the first ever game of Association football. The Strawberry Fair music and arts festival and Midsummer Fairs are held on Midsummer Common, and the annual Cambridge Beer Festival takes place on Jesus Green. -

Aaa Worldwise

AAA FALL 2017 WORLDWISE Route 66 Revival p. 32 Dressing for Access p. 38 South Africa: A Tale of Two Cities p. 48 TWO OF A KIND: THE ORIGINAL COLLEGE TOWNS Cambridge MASSACHUSETTS Just north of Boston and home to Harvard University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, this city oozes intellectualism and college spirit. COURTESY OF HARVARD UNIVERSITY HARVARD OF COURTESY Harvard and the Charles River STAY SEE When celebs come to Harvard, they’re put up at Harvard University’s three venerable art the AAA Four Diamond Charles Hotel. Just museums were brought under one roof in minutes from Harvard Yard, The Charles has a 2014 and collectively dubbed the Harvard well-stocked in-house library and one of the best Art Museums. Their collections include some breakfasts in town at Henrietta’s Table. The 250,000 art works dating from ancient times to 31-room luxury Hotel Veritas—described by the present and spanning the globe. The MIT a GQ magazine review as “a classic Victorian Museum, not surprisingly, focuses on science and mansion that went to Art Deco finishing technology. It includes the Polaroid Historical school”—boasts 24-hour concierge service Collection of cameras and photographs, the COURTESY OF HOTEL VERITAS HOTEL OF COURTESY and a location in Harvard Square. Those who MIT Robotics Collection and the world’s Hotel Veritas prefer to bed down near the Massachusetts most comprehensive holography collection. Institute of Technology (MIT) should check in Beyond the universities, visit the Longfellow at The Kendall Hotel, which brings boutique House–Washington’s Headquarters, the accommodations to a converted 19th-century preserved, furnished home of 19th-century poet firehouse. -

The Fen Edge Trail Walk

‘I love the mix on The Fen Edge Trail this walk.....the Walk: Cambridge to Fen Ditton history, the 4.1 miles (6.6 km) landscape, starting at especially the river’ a journey across a The Sedgwick Museum Penny, CGS Cambs Geosites Team landscape and time of Earth Sciences Peakirk: Lincs 20km 13.3f Leper Chapel border Isleham: Suffolk border 13.1f Stourbridge Common and River Cam 7.2f Darwin Garden Christ’s College Cambridge to Contours: 0m blue, 5m Fen Ditton walk yellow, 10m and above red. © Cambridgeshire Geological The route: ‘from revolutionary science to riverside meadows’ Society 2021 Contains OS data © Crown copyright and Fen Ditton database right 2017 Image N This walk, on the southern limit of the Fen Edge, takes you from the centre of Cambridge, one of Landsat Copernicus England’s most iconic cities, through characteristic water meadows to the riverside village of Fen Ditton. Starting at the famous Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences and with a short visit to the University of Cambridge Museum of Zoology, you pass the buildings that have witnessed some of the most remarkable work in the history of science from Darwin’s studies to Crick and Watson’s discovery of DNA. Both museums hold internationally important specimens and are worth extended visits themselves and the Sedgwick has published a Geology Trail featuring many of the building stones in the city. One of the other highlights of this walk to Fen Ditton is the journey along the River Cam. Rising from chalk springs in the hills to the south of the city, this important river flows north to join the River Ouse on its course to the Wash. -

Central Cambridge: a Guide to the University and Colleges: Second Edition Kevin Taylor Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-88876-9 - Central Cambridge: A Guide to the University and Colleges: Second Edition Kevin Taylor Frontmatter More information Central Cambridge A Guide to the University and Colleges SECOND EDITION Kevin Taylor © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-88876-9 - Central Cambridge: A Guide to the University and Colleges: Second Edition Kevin Taylor Frontmatter More information University Printing House, Cambridge CB2 8BS, United Kingdom Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York Cambridge University Press is part of the University of Cambridge. It furthers the University’s mission by disseminating knowledge in the pursuit of education, learning and research at the highest international levels of excellence. www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521717182 © Cambridge University Press 2008 This publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First edition published 1994 (reprinted 1996, 1997, 1999, 2003, 2004) Second edition published 2008 (reprinted 2011) 5th printing 2015 Printed in the United Kingdom by Bell and Bain Ltd, Glasgow A catalogue record for this publication is available from the British Library ISBN 978-0-521-88876-9 hardback ISBN 978-0-521-71718-2 paperback II © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-88876-9 - Central Cambridge: A Guide to the University and Colleges: Second Edition Kevin Taylor Frontmatter More information Contents General map of Cambridge Inside front cover Foreword by H.R.H. -

Expenditure by Institution (Summary)

18 January 2011 CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY REPORTER 17 Section C: Expenditure by Institution (summary) Note that this analysis takes into account financial accounting adjustments in respect of: the elimination of internal charges; capital expenditure; and depreciation. Costs by activity 2009–10 (£000) Costs by type 2009–10 (£000) Research Adminis- grants tration and Other Total costs Academic Academic and Other central Staff operating Deprec- Interest Total costs 2008–09 departments services contracts activities services Premises costs expenses iation payable 2009–10 (£000) ACADEMIC DEPARTMENTS SCHOOL OF ARTS AND HUMANITIES 231 – – – 7 (13) 197 28 – – 225 277 Anglo-Saxon, Norse and Celtic 634 6 79 10 20 – 669 80 – – 749 763 Architecture 1,309 1 1,547 87 (8) 5 1,725 1,216 – – 2,941 2,933 Architecture and History of Art 458 62 2 16 – 88 417 182 27 – 626 727 Classics and Classical Archaeology 2,927 183 526 83 250 38 3,386 621 – – 4,007 3,808 Divinity 2,319 130 717 29 184 70 2,562 887 – – 3,449 3,305 East Asian Studies 1,266 – – 16 8 – 1,101 189 – – 1,290 1,297 English 3,239 203 240 23 89 78 3,509 351 12 – 3,872 3,726 French 1,302 – 162 8 2 – 1,411 63 – – 1,474 1,438 German 852 3 38 – 5 – 873 25 – – 898 908 History of Art 517 – 29 17 7 – 528 42 – – 570 496 Italian 544 – 44 2 – – 574 16 – – 590 549 Linguistics 508 – 304 31 – – 719 124 – – 843 810 Middle Eastern Studies 961 1 – 1 78 – 840 201 – – 1,041 983 Modern and Medieval Languages 674 188 – 18 77 2 733 226 – – 959 889 Music 1,438 114 134 134 36 67 1,527 372 24 – 1,923 1,619 Oriental Studies -

FOI Ref 6871 Response Sent 17 March Can You Please Provide The

FOI Ref 6871 Response sent 17 March Can you please provide the following details from the most recent records which you hold under The Licensing Act 2003: On-trade alcohol licensed premises, including: Premises Licence Number Date Issued Premises Licence Status (active, expired etc.) Premises Name Premises Address Premises Postcode Premises Telephone Number Premises on-trade Category (e.g. Cafe, Bar, Theatre, Nightclub etc.) Premises Licence Holder Name Premises Licence Holder Address Premises Licence Holder Postcode Designated Premises Supervisor Name Designated Premises Supervisor Address Designated Premises Supervisor Postcode The information you have requested is held and in the attached. However the personal information relating to Designated Premises Supervisors you have requested is refused under the exemption to disclosure at Section 40(2) of the Act Further queries on this matter should be directed to [email protected] Full address Telephone number Licence type Status Date issued Licence holder 1 and 1 Rougamo Ltd, 84 Regent Street, Cambridge, 07730029914 Premises Licence Current Licence 10/03/2020 Yao Qin Cambridgeshire, CB2 1DP 2648 Cambridge, 14A Trinity Street, Cambridge, 01223 506090 Premises Licence Current Registration 03/10/2005 The New Vaults Limited Cambridgeshire, CB2 1TB 2nd View Cafe - Waterstones, 20-22 Sidney Street, Premises Licence Current Registration 17/09/2010 Waterstones Booksellers Ltd Cambridge, Cambridgeshire, CB2 3HG ADC Theatre, Park Street, Cambridge, Cambridgeshire, CB5 01223 359547 Premises Licence -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Environment Scrutiny Committee

Public Document Pack Cambridge City Council ENVIRONMENT SCRUTINY COMMITTEE To: Scrutiny Committee Members: Gawthrope (Chair), Bird (Vice-Chair), Bick, Ratcliffe, Sargeant, Sheil and Tunnacliffe Alternates: Councillors Abbott, Adey and Sinnott Executive Councillors: Blencowe (Executive Councillor for Planning Policy and Transport) and R. Moore (Executive Councilor for Environmental Services and City Centre) Despatched: Thursday, 15 June 2017 Date: Tuesday, 27 June 2017 Time: 5.30 pm Venue: Committee Room 1 & 2, The Guildhall, Market Square, Cambridge, CB2 3QJ Contact: Claire Tunnicliffe Direct Dial: 01223 457013 AGENDA 1 Apologies To receive any apologies for absence. 2 Declarations of Interest Members are asked to declare at this stage any interests that they may have in an item shown on this agenda. If any member of the Committee is unsure whether or not they should declare an interest on a particular matter, they should seek advice from the Monitoring Officer before the meeting. 3 Minutes (Pages 7 - 20) To approve the minutes of the meeting held on 17 January and 25 May 2017 as a correct record. 4 Public Questions Please see information at the end of the agenda. i 5 Decision Taken by Executive Councillor 5a Planning Application Fees-The Government’s Offer Director of Planning and Economic Development (Pages 21 - 44) Record of Urgent Decision taken by the Executive Councillor for Planning Policy and Transport. To note decision taken by the Executive Councillor for Planning Policy and Transport since the last meeting of the Environment Scrutiny Committee. Items for Decision by the Executive Councillor, Without Debate These Items will already have received approval in principle from the Executive Councillor. -

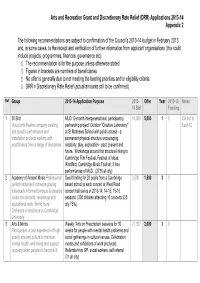

Arts and Recreation Grant and Discretionary Rate Relief (DRR) Applications 2013-14 Appendix 2

Arts and Recreation Grant and Discretionary Rate Relief (DRR) Applications 2013-14 Appendix 2 The following recommendations are subject to confirmation of the Council’s 2013-14 budget in February 2013 and, in some cases, to the receipt and verification of further information from applicant organisations (this could include projects, programmes, finances, governance etc). § The recommendation is for the purpose unless otherwise stated § Figures in brackets are numbers of beneficiaries § No offer is generally due to not meeting the funding priorities and/or eligibility criteria § DRR = Discretionary Rate Relief (actual amounts still to be confirmed) Ref Group 2013-14 Application Purpose 2013- Offer Year 2012-13 Notes 14 Bid Funding 1 30 Bird MUD 12-month intergenerational, participatory, 10,000 5,000 1 0 £5k bid to Visual arts theatre company creating partnership project. Outdoor "Creative Laboratory" East AC site specific performance and at St Matthews School with public access - a installation projects working with permanent physical structure encouraging practitioners from a range of disciplines creativity, play, exploration - past, present and future. Workshops around this structure linking to Cambridge Film Festival, Festival of Ideas, Wordfest, Cambridge Music Festival; 3 free performances of MUD. (2736 all city) 2 Academy of Ancient Music Professional Seed funding for 20 pupils from a Cambridge 3,500 1,500 3 0 period instrument orchestra playing based school to each concert at West Road historically informed baroque & classical concert hall series in 2013-14; 14-15; 15-16 music via concerts, recordings and seasons. (300 children attending 15 concerts 225 educational work. World tours. city 75%) Orchestra in residence at Cambridge University. -

Cambridge City Council and South Cambridgeshire District Council

CAMBRIDGE CITY COUNCIL AND SOUTH CAMBRIDGESHIRE DISTRICT COUNCIL INDOOR SPORTS FACILITY STRATEGY 2015-2031 JUNE 2016 OFFICIAL-SENSITIVE The table below lists the changes applied to the May 2016 version of the Indoor Sports Facility Strategy. Section of the Indoor Changes to the Indoor Sports Facility Strategy (RD/CSF/200) Sports Facility Strategy Whole document Reference to Indoor Facility/Facilities Strategy changed to Indoor Sports Facility Strategy Whole document Acronym IFS (for Indoor Facility/Facilities Strategy) changed to ISFS (for Indoor Sports Facility Strategy) Paragraph 2.11 Delete final sentence of paragraph as no map is provided. South Cambridgeshire District completely encircles Cambridge. South Cambridgeshire District is bordered to the northeast by East Cambridgeshire District, to the southeast by St Edmundsbury District, to the south by Uttlesford District, to the southwest by North Hertfordshire District, to the west by Central Bedfordshire and to the northwest by Huntingdonshire District. The neighbouring counties are shown on Map 2.2 below: Paragraph 5.320 Add additional sentence to the end of paragraph 5.320 to clarify the usage of squash facilities. All the pay and play squash facilities across Cambridge and South Cambridgeshire District are located on education sites; all but Kelsey Kerridge therefore have limited day time access. However, the majority of squash is played in evenings and weekends, so this is less of an issue than it is for sports hall provision. CAMBRIDGE CITY COUNCIL AND SOUTH CAMBRIDGESHIRE DISTRICT COUNCIL INDOOR SPORTS FACILITY STRATEGY TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 CAMBRIDGE AND SOUTH CAMBRIDGESHIRE DISTRICT - INDOOR SPORTS FACILITY STRATEGY (ISFS) 3 VISION 3 AIMS 3 NEEDS, PRIORITIES AND OPPORTUNITIES 4 NEW SETTLEMENTS BEYOND 2031 7 RECOMMENDATIONS 13 CAMBRIDGE AND SOUTH CAMBRIDGESHIRE DISTRICT COUNCIL - PLAYING PITCH STRATEGY (PPS) 16 2. -

MCR Handbook 2019

Information for New Graduates Murray Edwards College Information for New Graduates 2016-2017 Murray Edwards MCR MCR 2019 Dear new graduate, Welcome to Murray Edwards College! At this moment, our graduate community or “MCR” (see below) consists of over 200 Master’s and PhD students, coming from over 50 different countries and studying more than 90 different subjects. We are abso- lutely delighted to welcome you into this diverse, friendly and vibrant community. At the start of a Cambridge graduate degree, you are at the beginning of an exciting journey – both academically and personally. As your College “travel companions”, we would love to help make your Cambridge expe- rience the most enjoyable it can be. As you’re juggling the challenges of your degree and the numerous other opportunities Cambridge has to of- fer, your College is your home. It is a place where you can relax, socialise, make friends and receive the personal support you need. Our elected graduate Committee (or “MCR Committee”, see below) or- ganises a range of regular social events for Murray Edwards graduates and offers a wealth of support for your everyday graduate life. Addition- ally, at the beginning of your time in Cambridge, the Committee arranges two weeks of Freshers’ events to help you get to know Cambridge, the College and, most importantly perhaps, your fellow graduates. This booklet is the first part of this introduction. It aims to make your arrival that little bit easier, with useful information on getting settled in Cambridge and tips previous generations of students wanted to pass on.