Pazhassi Raja : a Revisit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Particulars of Some Temples of Kerala Contents Particulars of Some

Particulars of some temples of Kerala Contents Particulars of some temples of Kerala .............................................. 1 Introduction ............................................................................................... 9 Temples of Kerala ................................................................................. 10 Temples of Kerala- an over view .................................................... 16 1. Achan Koil Dharma Sastha ...................................................... 23 2. Alathiyur Perumthiri(Hanuman) koil ................................. 24 3. Randu Moorthi temple of Alathur......................................... 27 4. Ambalappuzha Krishnan temple ........................................... 28 5. Amedha Saptha Mathruka Temple ....................................... 31 6. Ananteswar temple of Manjeswar ........................................ 35 7. Anchumana temple , Padivattam, Edapalli....................... 36 8. Aranmula Parthasarathy Temple ......................................... 38 9. Arathil Bhagawathi temple ..................................................... 41 10. Arpuda Narayana temple, Thirukodithaanam ................. 45 11. Aryankavu Dharma Sastha ...................................................... 47 12. Athingal Bhairavi temple ......................................................... 48 13. Attukkal BHagawathy Kshethram, Trivandrum ............. 50 14. Ayilur Akhileswaran (Shiva) and Sri Krishna temples ........................................................................................................... -

KERALA SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT PROJECT (KSWMP) with Financial Assistance from the World Bank

KERALA SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT Public Disclosure Authorized PROJECT (KSWMP) INTRODUCTION AND STRATEGIC ENVIROMENTAL ASSESSMENT OF WASTE Public Disclosure Authorized MANAGEMENT SECTOR IN KERALA VOLUME I JUNE 2020 Public Disclosure Authorized Prepared by SUCHITWA MISSION Public Disclosure Authorized GOVERNMENT OF KERALA Contents 1 This is the STRATEGIC ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT OF WASTE MANAGEMENT SECTOR IN KERALA AND ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL MANAGEMENT FRAMEWORK for the KERALA SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT PROJECT (KSWMP) with financial assistance from the World Bank. This is hereby disclosed for comments/suggestions of the public/stakeholders. Send your comments/suggestions to SUCHITWA MISSION, Swaraj Bhavan, Base Floor (-1), Nanthancodu, Kowdiar, Thiruvananthapuram-695003, Kerala, India or email: [email protected] Contents 2 Table of Contents CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION TO THE PROJECT .................................................. 1 1.1 Program Description ................................................................................. 1 1.1.1 Proposed Project Components ..................................................................... 1 1.1.2 Environmental Characteristics of the Project Location............................... 2 1.2 Need for an Environmental Management Framework ........................... 3 1.3 Overview of the Environmental Assessment and Framework ............. 3 1.3.1 Purpose of the SEA and ESMF ...................................................................... 3 1.3.2 The ESMF process ........................................................................................ -

Realm of the Black Panther

Realm of the Black Panther Naturetrek Tour Itinerary Outline itinerary Day 1 Depart London. Day 2 Arrive Bengaluru, transfer to Nagarhole. Day 3/8 Kabini River Lodge. Day 9 Bengaluru (Bangalore). Day 10 Fly London Wayanad Wildlife Sanctuary extension Day 9/11 Wayanad Wildlife Sanctuary. Day 12 Bengaluru. Day 13 Fly London. Single room supplement £595 (extension: £195) Grading Grade A. Easy to moderate with occasional day walks. Focus Black Panther, other mammals and birds. Highlights ● Seven nights at spectacular Kabini River Lodge. ● Small group – maximum six people plus an expert Naturetrek naturalist guide. ● Explore Kabini by jeep and boat, searching for Blackie and other Leopards. ● Fantastic supporting cast includes Asian Elephants, Tigers, Gaur, and a chance of Dhole (Indian Wild Dog). ● Amazing birdlife, including endemic Blue-winged From top: Blackie, Tiger, Asian Elephant Parakeet, Malabar Grey Hornbill & White-bellied Treepie. Naturetrek Mingledown Barn Wolf’s Lane Chawton Alton Hampshire GU34 3HJ UK T: +44 (0)1962 733051 E: [email protected] W: www.naturetrek.co.uk Tour Itinerary Realm of the Black Panther ● Fly in and out of Bengaluru, on direct British Airways flights. ● Expertly escorted by an Indian Naturetrek naturalist. ● Top tip: extend tour with a stay in Wayanad Wildlife Sanctuary. Dates and cost 2020 Sunday 15th November — Tuesday 24th November 2020 Cost: £3,395 Post-tour extension to Wayanad: till Friday 27th November Cost: £995 2021 Friday 5th February – Sunday 14th February 2021 Cost: £3,395 Wayanad extension: -

Understanding REPORT of the WESTERNGHATS ECOLOGY EXPERT PANEL

Understanding REPORT OF THE WESTERNGHATS ECOLOGY EXPERT PANEL KERALA PERSPECTIVE KERALA STATE BIODIVERSITY BOARD Preface The Western Ghats Ecology Expert Panel report and subsequent heritage tag accorded by UNESCO has brought cheers to environmental NGOs and local communities while creating apprehensions among some others. The Kerala State Biodiversity Board has taken an initiative to translate the report to a Kerala perspective so that the stakeholders are rightly informed. We need to realise that the whole ecosystem from Agasthyamala in the South to Parambikulam in the North along the Western Ghats in Kerala needs to be protected. The Western Ghats is a continuous entity and therefore all the 6 states should adopt a holistic approach to its preservation. The attempt by KSBB is in that direction so that the people of Kerala along with the political decision makers are sensitized to the need of Western Ghats protection for the survival of themselves. The Kerala-centric report now available in the website of KSBB is expected to evolve consensus of people from all walks of life towards environmental conservation and Green planning. Dr. Oommen V. Oommen (Chairman, KSBB) EDITORIAL Western Ghats is considered to be one of the eight hottest hot spots of biodiversity in the World and an ecologically sensitive area. The vegetation has reached its highest diversity towards the southern tip in Kerala with its high statured, rich tropical rain fores ts. But several factors have led to the disturbance of this delicate ecosystem and this has necessitated conservation of the Ghats and sustainable use of its resources. With this objective Western Ghats Ecology Expert Panel was constituted by the Ministry of Environment and Forests (MoEF) comprising of 14 members and chaired by Prof. -

CPE Report 2011-12

ST.THOMAS COLLEGE, PALA ARUNAPURAM P.O. KOTTAYAM (DIST.) KERALA, PIN – 686574, Phone 04822-212317, Fax: 04822-216313 Website: www.stcp.ac.in Email: [email protected] , [email protected] (IDENTIFIED AS A COLLEEGE WITH POTENTIAL FOR EXCELLENCE) Annual Report regarding the steps taken under the CPE Programme of UGC during 2011-2012 The UGC has released a sum of Rs.50.00 lakhs in 2010-11 as first installment. A sum of Rs.40.00 lakhs has been sanctioned as second installment by UGC during 2011-12 but the amount has not yet been released. We have spent more than Rs.80.00 lakhs so far. Thanks to the CPE Programme of UGC, the college had introduced a number of innovative steps with regard to curriculum, teaching, evaluation etc. at undergraduate, post-graduate and research levels. The direct benefits have been obtained to more than 10000 students at UG and PG levels apart from 500 research scholars as well as 200 faculty members. Indirectly it has been beneficial to more than 50000 people in the Meenachil Taluk in Kottayam District which is an agricultural belt in Kerala. The Choice Based Credit and Semester System (CBCSS) has been introduced at UG level in all programmes by 2011 and this has been extended to PG programs by 2012. Continuous assessment as part of internal examinations was introduced with various components such as attendance, assignments, seminars and test papers. Each student has to prepare at least 2 assignments or term papers in each subject of study and present them in seminars. -

Power Politics in Kolathunadu (1663-1697)

The Ali Rajas of Cannanore: status and identity at the interface of commercial and political expansion, 1663-1723 Mailaparambil, J.B. Citation Mailaparambil, J. B. (2007, December 12). The Ali Rajas of Cannanore: status and identity at the interface of commercial and political expansion, 1663-1723. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/12488 Version: Not Applicable (or Unknown) Licence agreement concerning inclusion of doctoral thesis in the License: Institutional Repository of the University of Leiden Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/12488 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). CHAPTER SIX POWER POLITICS IN KOLATHUNADU (1663-1697) In the month of October 1690, three Dutch soldiers deserted from the Dutch fortress in Cannanore and were caught by the Nayars of the Kolathiri prince, Keppoe Unnithamburan, in Maday—a place some twenty kilometres to the north of Cannanore.1 Although they tried to hide their real identity by claiming first that they were English and later Portuguese, the Nayars who were sent by the Company to track them successfully exposed their pretensions. Realizing the graveness of the situation, the soldiers desperately pleaded with the Prince not to extradite them to the Company for fear of capital punishment. Moved by their pathetic imploring, the Prince took them under his protection and ordered the Company Nayars to turn back, stating that he would take them to Cannanore personally, which, in fact, did not happen. The Company servants complained about this incident to the Ali Raja. The latter assured them he would settle the issue by promising to advise and caution the inexperienced young prince regarding this issue. -

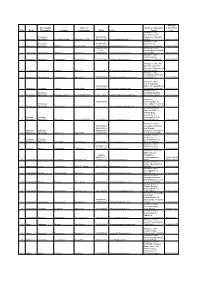

Sl.No. Block Panchayath/ Municipality Location Name of Entrepreneur Mobile E-Mail Address of Akshaya Centre Akshaya Centre Phone

Akshaya Panchayath/ Name of Address of Akshaya Centre Phone Sl.No. Block Municipality Location Entrepreneur Mobile E-mail Centre No Akshaya e centre, Chennadu Kavala, Erattupetta 9961985088, Erattupetta, Kottayam- 1 Erattupetta Municipality Chennadu Kavala Sajida Beevi. T.M 9447507691, [email protected] 686121 04822-275088 Akshaya e centre, Erattupetta 9446923406, Nadackal P O, 2 Erattupetta Municipality Hutha Jn. Shaheer PM 9847683049 [email protected] Erattupetta, Kottayam 04822-329714 9645104141 Akshaya E-Centre, Binu- Panackapplam,Plassnal 3 Erattupetta Thalappalam Pllasanal Beena C S 9605793000 [email protected] P O- 686579 04822-273323 Akshaya e-centre, Medical College, 4 Ettumanoor Arpookkara Panampalam Renjinimol P S 9961777515 [email protected] Arpookkara, Kottayam 0481-2594065 Akshaya e centre, Hill view Bldg.,Oppt. M G. University, Athirampuzha 5 Ettumanoor Athirampuzha Amalagiri Shibu K.V. 9446303157 [email protected] Kottayam-686562 0481-2730349 Akshaya e-centre, , Thavalkkuzhy,Ettumano 6 Ettumanoor Athirampuzha Thavalakuzhy Josemon T J 9947107199 [email protected] or P.O-686631 0418-2536494 Akshaya e-centre, Near Cherpumkal 9539086448 Bridge, Cherpumkal P O, 7 Ettumanoor Aymanam Valliyad Nisha Sham 9544670426 [email protected] Kumarakom, Kottayam 0481-2523340 Akshaya Centre, Ettumanoor Municipality Building, 8 Ettumanoor Muncipality Ettumanoor Town Reeba Maria Thomas 9447779242 [email protected] Ettumanoor-686631 0481-2535262 Akshaya e- 9605025039 Centre,Munduvelil Ettumanoor -

Self Study Report of GOVERNMENT BRENNEN COLLEGE

Self Study Report of GOVERNMENT BRENNEN COLLEGE SELF STUDY REPORT FOR 3rd CYCLE OF ACCREDITATION GOVERNMENT BRENNEN COLLEGE GOVERNMENT BRENNEN COLLEGE DHARMADAM, THALASSERY 670106 www.brennencollege.ac.in Submitted To NATIONAL ASSESSMENT AND ACCREDITATION COUNCIL BANGALORE December 2019 Page 1/117 09-03-2020 10:53:36 Self Study Report of GOVERNMENT BRENNEN COLLEGE 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1.1 INTRODUCTION Government Brennen College, Dharmadam, Thalassery is one of the premier institutions of higher education in the state of Kerala. With a tradition of 130 years, the college is catering to the comprehensive advancement of the various sections of the society in the region. Developed out of the Free School established in 1862 by Edward Brennen, the institution was elevated to the status of Grade II College in1890. It has now emerged as a centre of excellence with the status of ‘Heritage College’ by the UGC, one among the 19 colleges in India. The College offers 18 UG, 12 PG and One M. Phil course. There are eight research departments. The selection process to the courses is transparent. Due weightage is given to the marginalised, the differently-abled and the like categories who are provided with ample emotional and economic support so as to bring them to the main stream. The teaching, learning and evaluation procedures are being revised and updated from time to time. Well- designed Tutorial System, transparent Internal Assessment, fruitful remedial coaching etc. are the highlights of the institution. The meritorious academic community, led by resourceful faculty of national and international reputation testify the vibrant academic ambience of the college. -

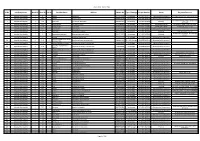

Sl No Localbody Name Ward No Door No Sub No Resident Name Address Mobile No Type of Damage Unique Number Status Rejection Remarks

Flood 2019 - Vythiri Taluk Sl No Localbody Name Ward No Door No Sub No Resident Name Address Mobile No Type of Damage Unique Number Status Rejection Remarks 1 Kalpetta Municipality 1 0 kamala neduelam 8157916492 No damage 31219021600235 Approved(Disbursement) RATION CARD DETAILS NOT AVAILABLE 2 Kalpetta Municipality 1 135 sabitha strange nivas 8086336019 No damage 31219021600240 Disbursed to Government 3 Kalpetta Municipality 1 138 manjusha sukrutham nedunilam 7902821756 No damage 31219021600076 Pending THE ADHAR CARD UPDATED ANOTHER ACCOUNT 4 Kalpetta Municipality 1 144 devi krishnan kottachira colony 9526684873 No damage 31219021600129 Verified(LRC Office) NO BRANCH NAME AND IFSC CODE 5 Kalpetta Municipality 1 149 janakiyamma kozhatatta 9495478641 >75% Damage 31219021600080 Verified(LRC Office) PASSBOOK IS NO CLEAR 6 Kalpetta Municipality 1 151 anandavalli kozhathatta 9656336368 No damage 31219021600061 Disbursed to Government 7 Kalpetta Municipality 1 16 chandran nedunilam st colony 9747347814 No damage 31219021600190 Withheld PASSBOOK NOT CLEAR 8 Kalpetta Municipality 1 16 3 sangeetha pradeepan rajasree gives nedunelam 9656256950 No damage 31219021600090 Withheld No damage type details and damage photos 9 Kalpetta Municipality 1 161 shylaja sasneham nedunilam 9349625411 No damage 31219021600074 Disbursed to Government Manjusha padikkandi house 10 Kalpetta Municipality 1 172 3 maniyancode padikkandi house maniyancode 9656467963 16 - 29% Damage 31219021600072 Disbursed to Government 11 Kalpetta Municipality 1 175 vinod madakkunnu colony -

Anglo-Mysore War

www.gradeup.co Read Important Medieval History Notes based on Mysore from Hyder Ali to Tipu Sultan. We have published various articles on General Awareness for Defence Exams. Important Medieval History Notes: Anglo-Mysore War Hyder Ali • The state of Mysore rose to prominence in the politics of South India under the leadership of Hyder Ali. • In 1761 he became the de facto ruler of Mysore. • The war of successions in Karnataka and Haiderabad, the conflict of the English and the French in the South and the defeat of the Marathas in the Third battle of Panipat (1761) helped him in attending and consolidating the territory of Mysore. • Hyder Ali was defeated by Maratha Peshwa Madhav Rao in 1764 and forced to sign a treaty in 1765. • He surrendered him a part of his territory and also agreed to pay rupees twenty-eight lakhs per annum. • The Nizam of Haiderabad did not act alone but preferred to act in league with the English which resulted in the first Anglo-Mysore War. Tipu Sultan • Tipu Sultan succeeded Hyder Ali in 1785 and fought against British in III and IV Mysore wars. • He brought great changes in the administrative system. • He introduced modern industries by bringing foreign experts and extending state support to many industries. • He sent his ambassadors to many countries for establishing foreign trade links. He introduced new system of coinage, new scales of weight and new calendar. • Tipu Sultan organized the infantry on the European lines and tried to build the modern navy. • Planted a ‘tree of liberty’ at Srirangapatnam and -

Anglo-Mysore Wars

ANGLO-MYSORE WARS The Anglo-Mysore Wars were a series of four wars between the British and the Kingdom of Mysore in the latter half of the 18th century in Southern India. Hyder Ali (1721 – 1782) • Started his career as a soldier in the Mysore Army. • Soon rose to prominence in the army owing to his military skills. • He was made the Dalavayi (commander-in-chief), and later the Chief Minister of the Mysore state under KrishnarajaWodeyar II, ruler of Mysore. • Through his administrative prowess and military skills, he became the de- facto ruler of Mysore with the real king reduced to a titular head only. • He set up a modern army and trained them along European lines. First Anglo-Mysore War (1767 – 1769) Causes of the war: • Hyder Ali built a strong army and annexed many regions in the South including Bidnur, Canara, Sera, Malabar and Sunda. • He also took French support in training his army. • This alarmed the British. Course of the war: • The British, along with the Marathas and the Nizam of Hyderabad declared war on Mysore. • Hyder Ali was able to bring the Marathas and the Nizam to his side with skillful diplomacy. • But the British under General Smith defeated Ali in 1767. • His son Tipu Sultan advanced towards Madras against the English. Result of the war: • In 1769, the Treaty of Madras was signed which brought an end to the war. • The conquered territories were restored to each other. • It was also agreed upon that they would help each other in case of a foreign attack. -

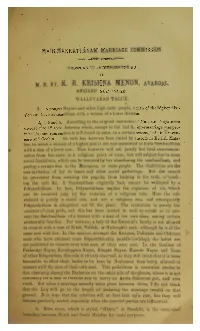

M. R Ry. K. R. Krishna Menon, Avargal, Retired Sub-Judge, Walluvanad Taluk

MARUMAKKATHAYAM MARRIAGE COMMISSION. ANSWERS TO INTERROGATORIES BY M. R RY. K. R. KRISHNA MENON, AVARGAL, RETIRED SUB-JUDGE, WALLUVANAD TALUK. 1. Amongst Nayars and other high caste people, a man of the higher divi sion can have Sambandham with a woman of a lower division. 2, 3, 4 and 5. According to the original institutes of Malabar, Nayars are divided into 18 sects, between whom, except in the last 2, intermarriage was per missible ; and this custom is still found to exist, to a certain extent, both in Travan core and Cochin, This rule has however been varied by custom in British Mala bar, in Avhich a woman of a higher sect is not now permitted to form Sambandham with a man of a lower one. This however will not justify her total excommuni cation from her caste in a religious point of view, but will subject her to some social disabilities, which can be removed by her abandoning the sambandham, and paying a certain fine to the Enangans, or caste-people. The disabilities are the non-invitation of her to feasts and other social gatherings. But she cannot be prevented from entering the pagoda, from bathing in the tank, or touch ing the well &c. A Sambandham originally bad, cannot be validated by a Prayaschitham. In fact, Prayaschitham implies the expiation of sin, which can be incurred only by the violation of a religious rule. Here the rule violated is purely a social one, and not a religious one, and consequently Prayaschitham is altogether out of the place. The restriction is purely the creature of class pride, and this has been carried to such an extent as to pre vent the Sambandham of a woman with a man of her own class, among certain aristocratic families.