Download File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jerry Garcia Song Book – Ver

JERRY GARCIA SONG BOOK – VER. 9 1. After Midnight 46. Chimes of Freedom 92. Freight Train 137. It Must Have Been The 2. Aiko-Aiko 47. blank page 93. Friend of the Devil Roses 3. Alabama Getaway 48. China Cat Sunflower 94. Georgia on My Mind 138. It Takes a lot to Laugh, It 4. All Along the 49. I Know You Rider 95. Get Back Takes a Train to Cry Watchtower 50. China Doll 96. Get Out of My Life 139. It's a Long, Long Way to 5. Alligator 51. Cold Rain and Snow 97. Gimme Some Lovin' the Top of the World 6. Althea 52. Comes A Time 98. Gloria 140. It's All Over Now 7. Amazing Grace 53. Corina 99. Goin' Down the Road 141. It's All Over Now Baby 8. And It Stoned Me 54. Cosmic Charlie Feelin' Bad Blue 9. Arkansas Traveler 55. Crazy Fingers 100. Golden Road 142. It's No Use 10. Around and Around 56. Crazy Love 101. Gomorrah 143. It's Too Late 11. Attics of My Life 57. Cumberland Blues 102. Gone Home 144. I've Been All Around This 12. Baba O’Riley --> 58. Dancing in the Streets 103. Good Lovin' World Tomorrow Never Knows 59. Dark Hollow 104. Good Morning Little 145. Jack-A-Roe 13. Ballad of a Thin Man 60. Dark Star Schoolgirl 146. Jack Straw 14. Beat it on Down The Line 61. Dawg’s Waltz 105. Good Time Blues 147. Jenny Jenkins 15. Believe It Or Not 62. Day Job 106. -

The Influence of Louis Armstrong on the Harlem Renaissance 1923-1930

ABSTRACT HUMANITIES DECUIR, MICHAEL B.A. SOUTHERN UNIVERSITY AT NEW ORLEANS, 1987 M.A. THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY, 1989 THE INFLUENCE OF LOUIS ARMSTRONG ON THE HARLEM RENAISSANCE 1923–1930 Committee Chair: Timothy Askew, Ph.D. Dissertation dated August 2018 This research explores Louis Armstrong’s artistic choices and their impact directly and indirectly on the African-American literary, visual and performing arts between 1923 and 1930 during the period known as the Harlem Renaissance. This research uses analyses of musical transcriptions and examples of the period’s literary and visual arts to verify the significance of Armstrong’s influence(s). This research also analyzes the early nineteenth century West-African musical practices evident in Congo Square that were present in the traditional jazz and cultural behaviors that Armstrong heard and experienced growing up in New Orleans. Additionally, through a discourse analysis approach, this research examines the impact of Armstrong’s art on the philosophical debate regarding the purpose of the period’s art. Specifically, W.E.B. Du i Bois’s desire for the period’s art to be used as propaganda and Alain Locke’s admonitions that period African-American artists not produce works with the plight of blacks in America as the sole theme. ii THE INFLUENCE OF LOUIS ARMSTRONG ON THE HARLEM RENAISSANCE 1923–1930 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF CLARK ATLANTA UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF ARTS IN HUMANITIES BY MICHAEL DECUIR DEPARTMENT OF HUMANITIES ATLANTA, GEORGIA AUGUST 2018 © 2018 MICHAEL DECUIR All Rights Reserved ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My greatest debt of gratitude goes to my first music teacher, my mother Laura. -

B. B. King (1925-2015) Homenatge Al Rei Del Blues Maig 2015

B. B. King (1925-2015) Homenatge al Rei del Blues Maig 2015 ■ INTRODUCCIÓN Riley B. King o Riley Ben King (Itta Bena, Misisipi, 16 de septiembre de 1925-Las Vegas, Nevada, 14 de mayo de 2015), más conocido como B.B. King, fue un músico, cantante y compositor estadounidense. Es ampliamente considerado uno de los músicos de blues más influyentes de todos los tiempos, ganando el apodo de «el Rey del Blues» y el renombre de «uno de los tres reyes (kings) de la guitarra blues» junto a Albert King y Freddie King. Según Edward M. Komara, King «introdujo un sofisticado estilo de solos basados en fluidas cuerdas [de guitarra] dobladas y brillantes vibratos que influirían prácticamente a todos los guitarristas de blues eléctrico que le siguieron». Los Beatles le mencionaron en la canción «Dig It» (1970). Además, la revista Rolling Stone lo situó en el puesto seis de la lista de los 100 mejores guitarristas de todos los tiempos y figura en el puesto 17 de la lista «Top 50 Guitarists of All Time» elaborada por Gibson. King fue introducido en el Salón de la Fama del Rock and Roll en 1987. Con los años, King desarrolló un estilo de guitarra identificable de su obra musical, con elementos prestados de Blind Lemon Jefferson, T-Bone Walker y otros y la fusión de géneros musicales como el blues, el jazz, el swing y el pop. Su guitarra eléctrica Gibson ES-335, apodada «Lucille», también da nombre a una línea de guitarras creada por la compañía en 1980. King es también reconocido por su prolífico directo, con un promedio de 250 ó 300 conciertos anuales durante la década de 1970. -

Bb King Albums Download B.B

bb king albums download B.B. King. Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article. B.B. King , byname of Riley B. King , (born September 16, 1925, near Itta Bena, Mississippi, U.S.—died May 14, 2015, Las Vegas, Nevada), American guitarist and singer who was a principal figure in the development of blues and from whose style leading popular musicians drew inspiration. What is B.B. King known for? American guitarist and singer B.B. King was a principal figure in the development of blues. Leading popular musicians drew inspiration from his style, and by the late 1960s rock guitarists were acknowledging his influence and priority; they introduced King and his guitar, Lucille, to a broader white public, who until then had heard blues chiefly in derivative versions. What is B.B. King's real name? B.B. King's real name is Riley B. King. What does the B.B. in B.B. King's name stand for? The B.B. in B.B. King's name stands for "Blues Boy." King acquired the name while working as a disc jockey in Memphis, Tennessee, in the United States. What was B.B. King's first number-one hit? B.B. King's first hit song was "Three O’Clock Blues" in 1951. What song is B.B. King famous for? "The Thrill Is Gone," recorded in 1969, was a major hit for B.B. King. The song earned King his first of the 15 Grammy Awards he received. King was reared in the Mississippi Delta, and gospel music in church was the earliest influence on his singing. -

Ð'ð¸ Ð'ð¸ Кð¸Ð½ð³

Би Би Кинг ÐÐ »Ð±ÑƒÐ¼ ÑÐ ¿Ð¸ÑÑ ŠÐº (Ð ´Ð¸ÑÐ ºÐ¾Ð³Ñ€Ð°Ñ„иÑÑ ‚а & график) Riding with the King https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/riding-with-the-king-921317/songs Deuces Wild https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/deuces-wild-1201643/songs Let the Good Times Roll https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/let-the-good-times-roll-779791/songs My Kind of Blues https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/my-kind-of-blues-3497480/songs Blues Summit https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/blues-summit-886042/songs Midnight Believer https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/midnight-believer-959384/songs B.B. King & Friends: 80 https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/b.b.-king-%26-friends%3A-80-3488082/songs King Size https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/king-size-6412043/songs Blues 'N' Jazz https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/blues-%27n%27-jazz-27818068/songs There Must Be a Better World https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/there-must-be-a-better-world-somewhere- Somewhere 7782768/songs Blues on the Bayou https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/blues-on-the-bayou-4930534/songs Ladies and Gentlemen... Mr. B.B. https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/ladies-and-gentlemen...-mr.-b.b.-king- King 24962990/songs Makin' Love Is Good for You https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/makin%27-love-is-good-for-you-4392018/songs L.A. -

ARSC Journal Encourages Recording Companies and Distributors to Send New Releases of Historic Recordings to the Recording Review Editor

COMPILED BY CHRISTINA MOORE Recordings Received This column lists historic recordings which have been defined as 20 years or older. Historic recordings with one or two recent selections may be included as well. The ARSC Journal encourages recording companies and distributors to send new releases of historic recordings to the Recording Review Editor. Arhoolie Productions, Inc.: Au Bal Antillais. Franco-Creole Biguines from Martinique. Selections by Orchestre Antillais de Alexandre Stellio; Orchestre Creole "Kaukira Boys" de C. Martial; Alphonso et son Orchestre Typique Antillais; Orchestre "Tagada-Biguine" de Alexandre Stellio; Orchestre Creole Delvi; Don Barreto et son Orchestre Cubain; Orchestre Du Bal Antillais; Sam Castandet et son Orchestre Antillais; Orchestre de la Boule Blanche; Orchestre Typique Martiniquais Charlery-Delouche; Orchestre Del's Jazz Biguine; Stellio et son Orchestre Creole. Arhoolie Folklyric CD-7013 (1992). CD, recorded 1929-51. Beto Villa. Father of Orquesta Tejana. Madre Mia; Rosita; En Mi Ranchito; Morir So:iiando; La Mensajera; Blanco y Negro; Las Gaviotas; Rosalia; Rock and Rye Polka; Un Rato No Mas; La Mucura; Yo Tuve un Amor; La Rielera; Consentida; Amor Que Malo Eres; Ya Viene Mi Amor; Rio Grande; Ni Por Favor; El Palco; San Buena Ventura; Ramona; Adi6s Mi Chaparrita; La Chapaneca; Mi Gabriela. Arhoolie CD-364 (1992). CD, recorded 1947-54. Big Maceo. The King of Chicago Blues Piano. Worried Life Blues; Ramblin' Mind Blues; County Jail Blues; Can't You Read; So Long Baby; Texas Blues; Tuff Luck Blues; I Got the Blues; Bye Bye Baby; Poor Kelly Blues; Some Sweet Day; Anytime For You; My Last Go Round; Since You Been Gone; Kidman Blues; I'm So Worried; Things Have Changed; My Own Troubles; Maceo's 32-20; Texas Stomp; Winter Time Blues; Detroit Jump; Won't Be a Fool No More; Big Road Blues; Chicago Breakdown. -

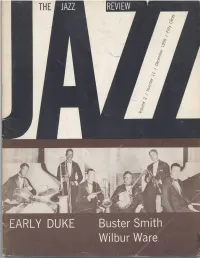

JREV2.11Full.Pdf

SPIRITUALS to SWING FROM THE FAMOUS CARNEGIE HALL CONCERTS — with such artists as: COUNT BASIE ORIGINAL ORCHESTRA • BENNY GOODMAN SEXTET • LESTER YOUNG • BUCK CLAYTON • SIDNEY BECHET • TOMMY LADNIER • JOE TURNER • HELEN HUMES • BIG BILL BROONZY • CHARLIE CHRISTIAN • JO JONES • JAMES P. JOHNSON • ALBERT AMMONS • "LIPS" PAGE • MEADE LUX LEWIS • PETE JOHNSON • Mitchell's Christian Singers • Fletcher Henderson • Ida Cox • Harry Edison • Herschel Evans • Lionel Hampton • Ed Lewis • Golden Gate Quartet • Sonny Terry • Bull City Red • Shad Collins • Kansas City Six • Earl Warren • Dickie Wells • Benny Morton • Arthur Bernstein • Jack Washington • Nick Fatool • Walter Page • Freddie Greene • Dan Minor Regular List Price $7.96 Special Jazz Collectors Price; 39 FOR THE TWO- RECORD SET Postage Prepaid on this item CHESTERFIELD MUSIC SHOPS, INC. 12 WARREN STREET NEW YORK 17, N. Y. for your Please send sets of John Hammond's Spirituals To Swing at the convenience special Collectors Price of $6.39 per set. $ enclosed. in Send FREE LP Catalog. ORDERING Name BY MAIL Address use this City Zone State handy blank Sorry no C.O.D. Discount Records—262 Sutter St., San Francisco, Calif. Special offer also available Discount Records—201 North La Salle, Chicago, Illinois from coast to coast at: Discount Records—202 Michigan Ave., Detroit, Michigan Chesterfield Music Shops—485 Madison Avenue, New York City, N. Y. Or take the next paragraph, same col• Naturally, when I speak of jazz, I speak umn, when I wrote, "the following prop• of a band style, an instrumental and LETTERS ositions are offered for consideration," orchestral style. It is not merely a use and what came out was "the following of blues scales nor for a notable proportions". -

The Gospel Ship Baptist Hymns & White Spirituals from the Southern

THE GOSPEL SHIP New World Records 80294 The Gospel Ship Baptist Hymns & White Spirituals from the Southern Mountains by Alan Lomax My years of field work in this country convince me that at least half our English-language musical heritage was religious. Indeed, until the rise of the modern entertainment industry most organized musical activity in most American communities centered on the church--for example, the backwoods singing schools discussed below (also see New World Records 80205, White Spirituals from the Sacred Harp) were usually church-sponsored. Today, as modernization wipes out the settings in which secular folk songs were created, the church continues to provide theaters in which new song styles arise to meet the needs of changing forms of worship. The religious revolution that began in the Reformation has continued in wave after wave of revivals, some large, some small, but most expressing the determination of some group to have the kind of music in church that they preferred and in which they could participate. This folk process has enriched the repertory of Protestantism with the patterns of many subcultures and many periods. Sometimes the people held on to old forms, like lining hymns (in which the preacher sings the first line and the congregation follows; see Track etc.) or spirituals, which the whole church sings, preferring them to a fancier program by the choir, to which the congregation passively listens. Bringing choirs and organs and musical directors into the southern folk church silenced the congregation and the spiritual in the once folky Baptist and Methodist churches, so that the folk moved out and founded the song-heavy sects of the Holiness movement. -

11469 Songs, 35.2 Days, 75.18 GB

Page 1 of 54 Music 11469 songs, 35.2 days, 75.18 GB Artist Album # Items Total Time Bryan Adams So Far So Good 13 59:05 Ryan Adams Easy Tiger 13 38:58 Adele 21 12 51:40 Aerosmith Aerosmith 8 35:51 Aerosmith Draw The Line 9 35:18 Aerosmith Get Your Wings 8 38:04 Aerosmith Honkin' On Bobo 12 43:55 Aerosmith Just Push Play 12 50:49 Aerosmith Pump 10 47:46 Aerosmith Toys In The Attic 9 37:11 Jan Akkerman Blues Root 1 3:03 Alice Cooper Welcome To My Nightmare 11 43:24 Luther Allison Blue Streak 12 53:32 Mose Allison Seventh Son 1 2:50 The Allman Brothers Band The Allman Brothers Band 6 33:23 The Allman Brothers Band Brothers And Sisters 7 38:24 The Allman Brothers Band Dreams [Disc 2] 10 1:16:00 The Allman Brothers Band Eat A Peach 9 1:09:56 The Allman Brothers Band An Evening With The Allman Brothers Band [1st Set] 9 1:14:08 The Allman Brothers Band An Evening With The Allman Brothers Band [2nd Set] 8 1:11:55 The Allman Brothers Band The Fillmore Concerts 2 41:36 The Allman Brothers Band Hittin' The Note 11 1:15:01 Music Page 2 of 54 Artist Album # Items Total Time The Allman Brothers Band Idlewild South 7 30:54 The Allman Brothers Band Live at the Fillmore East 10 1:32:44 The Allman Brothers Band Shades Of Two Worlds 8 52:36 The Allman Brothers Band Where It All Begins 10 56:02 Gregg Allman Laid Back 8 36:01 America Here & Now [Disc 1] 12 44:16 America Here & Now [Disc 2] 12 40:38 Tori Amos Crucify 1 3:11 Trey Anastasio Trey Anastasio 12 1:00:07 Eric Andersen Blue River 11 46:54 Ian Anderson The Secret Language Of Birds [Bonus Tracks] 18 -

Sommaire Catalogue Jazz / Blues Octobre 2011

SOMMAIRE CATALOGUE JAZZ / BLUES OCTOBRE 2011 Page COMPACT DISCS Blues .................................................................................. 01 Multi Interprètes Blues ....................................................... 08 Jazz ................................................................................... 10 Multi Interprètes Jazz ......................................................... 105 SUPPORTS VINYLES Jazz .................................................................................... 112 DVD Jazz .................................................................................... 114 L'astérisque * indique les Disques, DVD, CD audio, à paraître à partir de la parution de ce bon de commande, sous réserve des autorisations légales et contractuelles. Certains produits existant dans ce listing peuvent être supprimés en cours d'année, quel qu'en soit le motif. Ces articles apparaîtront de ce fait comme "supprimés" sur nos documents de livraison. BLUES 1 B B KING B B KING (Suite) Live Sweet Little Angel – 1954-1957 Selected Singles 18/02/2008 CLASSICS JAZZ FRANCE / GEFFEN (SAGAJAZZ) (900)CD 18/08/2008 CLASSICS JAZZ FRANCE / SAGA (949)CD #:GACFBH=YYZZ\Y: #:GAAHFD=VUU]U[: Live At The BBC 19/05/2008 CLASSICS JAZZ FRANCE / EMARCY The birth of a king 10.CLASS.REP(SAGAJAZZ) (899)CD 23/08/2004 CLASSICS JAZZ FRANCE / SAGA (949)CD #:GAAHFD=U[XVY^: #:GACEJI=WU\]V^: One Kind Favor 25/08/2008 CLASSICS JAZZ FRANCE / GEFFEN Live At The Apollo(ORIGINALS (JAZZ)) (268)CD 28/04/2008 CLASSICS JAZZ FRANCE / GRP (899)CD #:GACFBH=]VWYVX: -

The Memphis and Shelby County Room Music Listening Station Guide

The Memphis and Shelby County Room Music Listening Station Guide 1 The Memphis and Shelby County Room Music Listening Station Guide Instructions for Use Sign in at the Reference Desk for a pair of headphones Use this Guide to determine which album(s) you would like to listen to Power on the Receiver and the CD Changer Use the scroll wheel to select you album Push “Play” If others are waiting to listen, please limit your time to 2 hours After listening, turn off the Changer/ Receiver and return headphones to the Reference Desk Please do not open the Disc Changer or change any settings on the Changer or Receiver 2 CD Genre Artist Album Title Track Listing # Memphis blues / W. C. Handy - Tiger rag / D. J. LaRocca - Good news / Traditional spiritual, arr. Allen Todd II - A mess of blues / D. Pomus and M. Shuman - Let's stay together / Willie Mitchell, Al Green, Al Jackson - Fight song / Tom Ferguson - String quartet no.3, DRequiem : Oro Supplex/Lacrimosa ; Dies irae / John Baur - Ol' man The University 90 Years of making music river / Jerome Kern, arr. by James Richens - Allie call the beasts : Allie ; To be called Classical of Memphis in Memphis The 1 a bear / John David Peterson - Tender land : Stomp your foot upon the floor / Aaron Band University of Memphis Copland - I'm in trouble / Joe Hicks - MKG variations / Kamran Ince - Pockets : Three solos for double bass : number 1 / John Elmquist - Scherzo no.3 in c-sharp minor, op.39 / Frederic Chopin - Brass quintet : Intrada ; Finale / James Richens - Lucia di Lamermoor / Chi me frena in tal momento / Gaetano Donizetti. -

Gardenhire Defends Failed Voucher Bill

FRIDAY 161st YeAR • NO. 13 MAY 15, 2015 ClevelAND, TN 22 PAGeS • 50¢ Gardenhire defends failed voucher bill State senator provides Two senators respond updates on legislation to critics of ‘no’ votes By CHRISTY ARMSTRONG summary, the bill would have By TONY EUBANK accepting additional federal funds as Banner Staff Writer allowed a public school student Banner Staff Writer provided under the Affordable Care attending a school “in the bottom 5 Act. State Sen. Todd Gardenhire is still percent of schools in overall achieve- Local state senators Mike Bell and In a news release, Walter Davis, maintaining his support for bills ment” to receive a voucher they could Todd Gardenhire fired back against executive director accusations of hypocrisy after a state which did not pass in this year’s use to go to private school. of the Tennessee General Assembly session in agency released documents detailing Health Care “It doesn’t affect Bradley County,” the cost of health insurance premi- Nashville. Gardenhire said. Campaign, stated, Among the issues the proposed ums paid on behalf of the two law- “These numbers He explained the schools in the makers who voted against expanding bills addressed are wanting parents state falling in the bottom 5 percent reveal a stunning TennCare. hypocrisy. The to have the ability to send their kids are currently located in counties with According to reports, Tennessee to private schools with publicly fund- larger cities. loudest opponents taxpayers have paid about $5.8 mil- of a legislative ed vouchers and wanting to offer in- Gardenhire, whose District 10 lion in premiums since 2008, while state college tuition rates to children includes parts of Bradley and debate on Insure lawmakers have paid in about $1.4 Tennessee receive of “undocumented immigrants.” Hamilton counties, said Chattanooga million themselves.