Anstey,, Hormede, Meesden, Pelham & Wyddial in The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Herts Archaeology -- Contents

Hertfordshire Archaeology and History contents From the 1880s until 1961 research by members of the SAHAAS was published in the Society’s Transactions. As part of an extensive project, digitised copies of the Transactions have been published on our website. Click here for further information: https://www.stalbanshistory.org/category/publications/transactions-1883-1961 Since 1968 members' research has appeared in Hertfordshire Archaeology published in partnership with the East Herts Archaeological Society. From Volume 14 the name was changed to Hertfordshire Archaeology and History. The contents from Volume 1 (1968) to Volume 18 (2016-2019) are listed below. If you have any questions about the journal, please email [email protected]. 1 Volume 1 1968 Foreword 1 The Date of Saint Alban John Morris, B.A., Ph.D. 9 Excavations in Verulam Hills Field, St Albans, 1963-4 Ilid E Anthony, M.A., Ph.D., F.S.A. 51 Investigation of a Belgic Occupation Site at A G Rook, B.Sc. Crookhams, Welwyn Garden City 66 The Ermine Street at Cheshunt, Herts. G R Gillam 68 Sidelights on Brasses in Herts. Churches, XXXI: R J Busby Furneaux Pelham 76 The Peryents of Hertfordshire Henry W Gray 89 Decorated Brick Window Lintels Gordon Moodey 92 The Building of St Albans Town Hall, 1829-31 H C F Lansberry, M.A., Ph.D. 98 Some Evidence of Two Mesolithic Sites at Bishop's A V B Gibson Stortford 103 A late Bronze Age and Romano-British Site at Thorley Wing-Commander T W Ellcock, M.B.E. Hill 110 Hertfordshire Drawings of Thomas Fisher Lieut-Col. -

Buntingford Community Area Neighbourhood Plan Buntingford Community

BUNTINGFORD COMMUNITY AREA NEIGHBOURHOOD PLAN BUNTINGFORD COMMUNITY AREA NEIGHBOURHOOD PLAN 2014 - 2031 1 Six Parishes – One Community BUNTINGFORD COMMUNITY AREA NEIGHBOURHOOD PLAN Contents Page Foreword 3 Introduction 5 What is the Neighbourhood Plan? 5 How the Neighbourhood Plan fits into the Planning System 5 The Buntingford Community Area Today 7 Aspenden 7 Buckland and Chipping 8 Buntingford 9 Cottered 11 Hormead 12 Wyddial 14 Issues that have influenced the development of the 15 Neighbourhood Plan The Vision Statement for the Neighbourhood Plan 22 Neighbourhood Plan Policies 24 Introduction 24 Business and Employment (BE) 25 Environment and Sustainability (ES) 34 Housing Development (HD) 40 Infrastructure (INFRA) 47 Leisure and Recreation (LR) 54 Transport (T) 57 Monitoring 64 The Evidence Base 64 Appendices Appendix 1 - Buntingford and the Landscape of the East Herts Plateau 65 Appendix 2 - Spatial Standards in Buntingford since 1960 73 Appendix 3 - Housing Numbers in the BCA since 2011 77 Appendix 4 - Design Code 83 Appendix 5 - Impact of insufficient parking spaces in the BCA 86 Appendix 6 - Environment & Sustainability - BCA Local Green Spaces 89 2 Six Parishes – One Community BUNTINGFORD COMMUNITY AREA NEIGHBOURHOOD PLAN Foreword The popularity and attraction of the Market Town of Buntingford and the surrounding Villages of Aspenden, Buckland & Chipping, Cottered, Hormead, Wyddial, (referred to hereafter as the Buntingford Community Area (BCA) is principally based on the separate characters of the six parishes and their settlements. This includes their geographical location within and overlooking the Rib Valley, with the open landscape of arable fields and hedgerows which surround the settlements (see BCA Map of the Neighbourhood Plan area), and the presence of patches and strips of ancient woodland throughout the area. -

People Around the Diocese the Diocese of St Albans in Bedfordshire, Hertfordshire, Luton & Barnet

People around the Diocese The Diocese of St Albans in Bedfordshire, Hertfordshire, Luton & Barnet is to become Vicar in the benefice of on Faith & Science. Clergy Appointments Norton. Kate Peacock, has been appointed as Dean of Women’s Ministry. She presently holding Public Arun Arora, will continue with her roles as Rector Preacher’s License in the diocese Diocesan Appointments of Hormead, Wyddial, Anstey, Brent and Director of Communications for Pelham and Meesden, and Rural Dean the National Institutions of the Church Peter Crumpler has been appointed of Buntingford. of England is to become Vicar of St SSMs’ Officer for the Archdeaconry of Nicholas’ Church, Durham. St Albans and continues as Associate Minister at St Leonard’s Church James Faragher, presently Assistant Obituaries Sandridge. Curate at St Paul’s Church, St Albans is to become Priest-in-Charge in the Dr Nicholas Goulding presently SSM It is with sadness that we announce Benefice of St Oswald with St Aldate’s with PtO in the diocese is to become the death of James Wheen, Reader churches, Coney Hill, Oxford diocese. Public Preacher and Diocesan Advisor Emeritus from Redbourn. Michelle Grace, previously Curate in the benefice of St Oswald’s, Oswestry Reader Licensing and Rhydycroesau in Lichfield diocese, is to become Team Vicar in Tring Team (with special responsibility for St John’s Aldbury). Ben Lewis, presently Assistant Curate in Training in the benefice of Goldington, is to become Vicar of St Mark’s Church Wellingborough, in Peterborough diocese. Margaret Marshall, presently Rector in the Riversmeet benefice is to retire to Ely diocese. -

Final Recommendations on the Future Electoral Arrangements for East Hertfordshire

LOCAL GOVERNMENT COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND FINAL RECOMMENDATIONS ON THE FUTURE ELECTORAL ARRANGEMENTS FOR EAST HERTFORDSHIRE Report to the Secretary of State for the Environment, Transport and the Regions February 1998 LOCAL GOVERNMENT COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND LOCAL GOVERNMENT COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND This report sets out the Commission’s final recommendations on the electoral arrangements for East Hertfordshire. Members of the Commission are: Professor Malcolm Grant (Chairman) Helena Shovelton (Deputy Chairman) Peter Brokenshire Professor Michael Clarke Robin Gray Bob Scruton David Thomas O.B.E Adrian Stungo (Chief Executive) ©Crown Copyright 1998 Applications for reproduction should be made to: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office Copyright Unit The mapping in this report is reproduced from OS mapping by The Local Government Commission for England with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, © Crown Copyright. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown Copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. Licence Number: GD 03114G. ii LOCAL GOVERNMENT COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND CONTENTS page LETTER TO THE SECRETARY OF STATE v SUMMARY vii 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 CURRENT ELECTORAL ARRANGEMENTS 3 3 DRAFT RECOMMENDATIONS 7 4 RESPONSES TO CONSULTATION 9 5 ANALYSIS AND FINAL RECOMMENDATIONS 11 6 NEXT STEPS 25 APPENDICES A Final Recommendations for East Hertfordshire: Detailed Mapping 27 B Draft Recommendations for East Hertfordshire (August 1997) 35 LOCAL GOVERNMENT COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND iii iv LOCAL GOVERNMENT COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND Local Government Commission for England 3 February 1998 Dear Secretary of State On 10 December 1996 the Commission commenced a periodic electoral review of the district of East Hertfordshire under the Local Government Act 1992. -

Appendix C – Regulation 18 Consultees Specific Consultation Bodies • Anglian Water • British Waterways • Communication O

Appendix C – Regulation 18 Consultees Specific Consultation Bodies Anglian Water British Waterways Communication Operators (including; British Telecommunications plc, Hutchinson 3G UK Limited, Orange Personal Communications Services, T- Mobile, Telefonica O2 UK Ltd, Vodafone) Department for Transport Rail Group East and North Hertfordshire NHS Trust East of England Development Agency East of England Local Government Association East of England Regional Office English Heritage (now Historic England) Environment Agency Government Office for the East of England Greater Anglia Hertfordshire Constabulary Hertfordshire County Council Hertfordshire Highways Hertfordshire Local Enterprise Partnership Highways Agency (now Highways England) Homes and Communities Agency Lee Valley Regional Park Authority Mobile Operators Association National Grid Natural England Neighbouring Authorities (including; Broxbourne Borough Council, Epping Forest District Council, Essex County Council, North Hertfordshire District Council, Harlow District Council, Stevenage Borough Council, Uttlesford District Council, Welwyn Hatfield Borough Council) Network Rail NHS East of England NHS Hertfordshire NHS West Essex Other Hertfordshire Authorities (including; Dacorum Borough Council, Hertsmere Borough Council, St Albans District Council, Three Rivers District Council, Watford Borough Council) Thames Water The Coal Authority The Princess Alexandra Hospital NHS Trust Veolia Water East Herts Town and Parish Councils Bishop’s Stortford Town Council -

Brent Pelham & Meesden 2015

Brent Pelham & Meesden Map East Herts Ref(s) Wildlife & Countryside Act 1981 The Definitive Map & Statement of Public Rights of Way in Hertfordshire 2015 Statement 001 BR HCC 16 Commences from county road at Meesden Green thence S along Willoughby Lane to join county road near the Kennels. Width Limitations 003 FP HCC 16 Commences at county road S of Parish Room thence SE to join BR1. Width Limitations 006 FP HCC 16 Commences at Meesden Green thence W, S and W to parish boundary. Width Limitations 007 FP HCC 16 Commences at the "Fox" P.H. Meesden Green thence generally NW to parish boundary E of Five Acre Wood. Width Limitations 008 FP HCC 16 Commences at FP7 west of the "Fox" P.H. thence S to join FP6. Width Limitations 009 FP HCC 16 Commences from Anstey Road, Meesden Green, E of "Fox" P.H. thence NE to Wood Lane at Meesden Manor Entrance. Width Limitations 04 December 2015 Page 1 Brent Pelham & Meesden Map East Herts Ref(s) 010 BR HCC 16 Commences at county road, Meesden Green, thence NE along Wood Lane past entrance to Meesden Manor to junction with FP's 11 and 12 E of Manor House. Width Limitations 011 FP HCC 16 Continuation of BR10 thence NE to county road at Meesden Bury. Width Limitations 012 FP HCC 16 Commences at BR10 (Wood Lane) thence N passing E of Meesden Manor to parish boundary. Width Limitations 013 FP HCC 16 Commences at Clavering Road N of Meesden Bury thence NE and N running parallel with county boundary thence NW to meet boundary S of New Farm, Lower Green. -

St Edmund's Area

0 A10 1 9 A Steeple Litlington Little Morden A505 ChesterfordA St Edmund’s College B184 120 A1 Edworth & Prep School Royston Heydon Hinxworth Strethall Ashwell Littlebury Great Old Hall 1039 Chishill Elmdon Saffron A505 B GreenChrishall M11 Walden Astwick Caldecote B1039 DELIVERIES Church End Little Littlebury Therfield Chishill EXIT Green Newnham Wendens B184 A507 Stotfold Slip End Bridge Ambo 10 Duddenhoe Green Bygrave Kelshall Reed End B1052 B1383 Radwell 0 1 Langley A1(M) A10 MAIN A Sandon DELIVERIES Upper Green Langley ENTRANCE Norton B Arkesden Newport Buckland 1 Lower Green Baldock Roe 3 Wallington 6 Green 8 Wicken Mill End Meesden Bonhunt LETCHWORTH Chipping Clavering A5 Widdington Clothall 07 Rickling Willian Rushden Wyddial 9 Starlings Green Throcking Hare B1038 Nurseries Quendon Walsworth Weston Street Brent Pelham Berden M11 HITCHIN Cottered Stocking Henham Hall’s Cromer Buntingford Pelham B1383 Green Ugley Graveley Aspenden Ardeley East End Ugley Green 8 B1037 B1368 Manuden 1 St Westmill A10 105 Ippollytts Walkern Hay Street B Patmore Heath ( ) Wood End Stansted Elsenham A1 M Braughing B656 Clapgate Mountfitchet STEVENAGE Nasty Albury Great Munden Farnham Aston Benington Albury End End Little Haultwick Levens Puckeridge Hadham STANSTED Langley Green BISHOP’S AIRPORT B651 Wellpond 7 Aston Green A120 STORTFORD St Paul’s Dane End Standon Walden INSET Hadham 8 8a A120 Whempstead Ford Bury Green B1256 Takeley A602 Collier’s End Latchford Old Knebworth Street Knebworth Watton B1004 Thorley Street Datchworth at Stone Sacombe A10 -

A Happy Christmas to Us All and Let's Hope That Our New Year to Come

- . DECEMBER 2020 to JANUARY 2021 Diary of Events Date Event (unless cancelled in the meantime!) Dec 7th - Yew Tree Alpacas Christmas Shop 10.30 am to 4.30 pm each 12th day A Happy Christmas to us all and let’s hope that our New Year to come will see the back of Covid and lockdowns! Editor: Dave Oxley 2 Castle Cottages, Anstey [email protected] 01763 848584 Please send in your own news to: Jackie Godfrey on 01763 848732 or [email protected] (for Anstey) ; Martin Hugi [email protected] (for Brent Pelham): Meesden material for the time being direct to the editor; and for last minute material, direct to the editor. The next deadline is 15th January 2021 Cherry Blossom Time in Japan – some colours to cheer us up through the winter months and a link (press Ctrl plus click on the link below) to a few minutes of blossom magic: - https://www.bing.com/videos/search?q=japanese+bloosom+video&view=detail&mid=80C41C3B32A77FEA C9B780C41C3B32A77FEAC9B7&FORM=VIRE THE EDITORSHIP OF THIS NEWSLETTER. As announced earlier the current editors are standing down and this edition is their last. We are so grateful to Dave Oxley, of Castle Cottages, Anstey, for taking over and ensuring the survival of the Newsletter, and we wish him well for the future. A VERY SAD LOSS. You will no doubt have heard the news that Margaret Beach, who acted as the Meesden local editor and correspondent for this newsletter (among many other village roles) sadly died on the 26th October. She will be really missed by so many and our sincere condolences go to husband Stephen and daughters Heather and Wendy and all the rest of her family and to her many friends. -

Area 143.Qxd

WYDDIAL PLATEAU summary assessment evaluation guidelines area143 area 143 Buntingford County Map showing location of LANDSCAPE CHARACTER AREA Stevenage ©Crown copyright .All rights reserved. Puckeridge Hertfordshire County Council /Standon Bishops Stortford 100019606 2004 Watton -at- Stone Ware Sawbridgeworth Hertford LOCATION at Buntingford. The area is located on the elevated plateau between the valleys of the River Quin to the east and the River Rib to KEY CHARACTERISTICS the west. It stretches from Wyddial in the north to Hay • gently undulating plateau Street in the south. • predominantly arable land use • field sizes generally medium to large with some historic LANDSCAPE CHARACTER continuity but locally interrupted The character area comprises an elevated arable landscape • isolated but distinctive country houses set in small with extensive views over a gently undulating plateau. parklands There is a moderately strong historic character to the north • small to medium discrete woods resulting from the winding lanes, retained field patterns • plateau crossed by sinuous lanes from east to west and scattered woodland cover while to the south the character is more open. Settlement typically comprises DISTINCTIVE FEATURES isolated farms and occasional cottage groups. The most • Wyddial Hall and relic parkland distinctive areas are located near the larger houses including • Owles Hall - castellated Alswick and at Wyddial where the hall and core of the • Sainsbury's distribution depot village retain an important focus. The major detractors are • high voltage electricity pylons the high voltage electricity cables and pylons that dwarf • ponds local features on the plateau and the Sainsbury's warehouse • Power lines near Brown’s Corner (J.Billingsley) East Herts District Landscape Character Assessment pg 212 WYDDIAL PLATEAU summary assessment evaluation guidelines area 143 PHYSICAL INFLUENCES The area is characterised by isolated farmsteads and houses, Geology and soils. -

162912442.Pdf

Emily Mitchell Patronage and Politics at Barking Abbey, c. 950 - c. 1200 Abstract This thesis is a study of the Benedictine abbey of Barking in Essex from the tenth to the twelfth centuries. It is based on a wide range of published and unpublished documentary sources, and on hagiographie texts written at the abbey. It juxtaposes the literary and documentary sources in a new way to show that both are essential for a full understanding of events, and neither can be fully appreciated in isolation. It also deliberately crosses the political boundary of 1066, with the intention of demonstrating that political events were not the most significant determinant of the recipients of benefactors’ religious patronage. It also uses the longer chronological scale to show that patterns of patronage from the Anglo-Saxon era were frequently inherited by the incoming Normans along with their landholdings. Through a detailed discussion of two sets of unpublished charters (Essex Record Office MSS D/DP/Tl and Hatfield, Hatfield House MS Ilford Hospital 1/6) 1 offer new dates and interpretations of several events in the abbey’s history, and identify the abbey’s benefactors from the late tenth century to 1200. As Part III shows, it has been possible to trace patterns of patronage which were passed down through several generations, crossing the political divide of 1066. Royal patronage is shown to have been of great significance to the abbey, and successive kings exploited their power of advowson in different ways according to the political atmosphere o f England. The literary sources are discussed in a separate section, but with full reference to the historical narrative. -

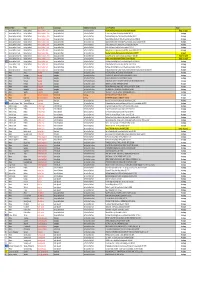

Copy of Polling Scheme Summary Current Provision.Xlsx

PD Ref Parish Ward Parish District Ward County Division Parliamentary Constituency Current Polling Place Change CD Bishops Stortford - All Saints Bishops Stortford Bishops Stortford All Saints Bishops Stortford East Hertford and Stortford All Saints JMI School, Parsonage Lane, Bishops Stortford CM23 5BE Change - see page 1 CE Bishops Stortford - All Saints Bishops Stortford Bishops Stortford All Saints Bishops Stortford East Hertford and Stortford All Saints Vestry, Stanstead Road, Bishops Stortford CM23 2DY No change CF Bishops Stortford - All Saints Bishops Stortford Bishops Stortford All Saints Bishops Stortford East Hertford and Stortford Thorn Grove Primary School, Thorn Grove, Bishops Stortford CM23 5LD No change CG Bishops Stortford - Central Bishops Stortford Bishops Stortford Central Bishops Stortford West Hertford and Stortford Wesley Hall, Methodist Church, 34B South Street, Bishops Stortford CM23 3AZ No change CH Bishops Stortford - Central Bishops Stortford Bishops Stortford Central Bishops Stortford West Hertford and Stortford Havers Community Centre, 1 Knights Row, Waytemore Road, Bishops Stortford CM23 3GR No change CI Bishops Stortford - Central Bishops Stortford Bishops Stortford Central Bishops Stortford West Hertford and Stortford Thorley Community Centre, Frieberg Avenue, Bishops Stortford CM23 4RF No change CJ Bishops Stortford - Central Bishops Stortford Bishops Stortford Central Bishops Stortford West Hertford and Stortford Rhodes Arts Complex, South Road, Bishops Stortford CM23 3JG No change CA Bishops Stortford -

Section 5: Admission Rules for Community and Voluntary-Controlled

Cheshunt School Admission arrangements for 2016/17 The school will have a published admission number of 150 Section 324 of the Education Act 1996 requires the governing bodies of all maintained schools to admit a child with a statement of special educational needs that names their school. All schools must also admit children with an Education, Health and Care Plan (EHCP) that names the school. Rule 1 Children looked after and children who were previously looked after, but ceased to be so because they were adopted (or became subject to a child arrangement order or a special guardianship order). Rule 2 Medical or Social: Children for whom it can be demonstrated that they have a particular medical or social need to go to the school. A panel of Hertfordshire Admissions and Transport Officers will determine whether the evidence provided is sufficiently compelling to meet the requirements for this rule on behalf of the Governors. The evidence must relate specifically to the school applied for under Rule 2 and must clearly demonstrate why it is the only school that can meet the child’s needs. Rule 3 Sibling: Children who have a sibling at the school at the time of application (including children looked after and/or previously looked after), unless the sibling is in the last year of the normal age-range of the school. Note: the ‘normal age range’ is the designated range for which the school provides, for example Years 7 to 11 in a 11-16 secondary school, Years 7 to 13 in a 11-18 school.