Understanding the Limits to Ethnic Change: Lessons from Uganda’S “Lost Counties”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report of the Colonies. Uganda 1920

This document was created by the Digital Content Creation Unit University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign 2010 COLONIAL REPORTS—ANNUAL. No. 1112. UGANDA. REPORT FOR 1920 (APRIL TO DECEMBER). (For Report for 1919-1920 see No. 1079.) LONDON: PRINTED AND PUBLISHED BY HIS MAJESTY'S STATIONERY OFFICE. To be purchased through any T3ookscller or directly from H.M. STATIONERY OFFICE at the following addresses: IMPERIAL HOUSE, KINGSWAY, LONC-ON, W.C.2, and 28, ABINGDON STREET, LONDON, S.W.I; 37, PETER STREET, MANCHESTER; 1, ST. ANDREW'S CRESCENT, CARDIFF; 23, FORTH STREET, EDINBURGH; or from EASON & SON. LTD., 40-41, LOWER SACKVII.I-E STREET, DUBLIN. 1922. Price 9d. Net. INDEX. PREFACE I. GENERAL OBSERVATIONS II. GOVERNMENT FINANCE III. TRADE, AGRICULTURE AND INDUSTRIES IV. LEGISLATION V. EDUCATION VI. CLIMATE AND METEOROLOGY VII. COMMUNICATIONS.. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS' RECEIVED &0dUM£NT$ DIVISION -fTf-ViM-(Hff,>itmrtn«l,.ni ii ii in. No. 1112. Annual Report ON THE Uganda Protectorate FOR THE PERIOD 1st April to 31st December 1920.* PREFACE. 1. Geographical Description.—The territories comprising the Uganda Protectorate lie between Belgian Congo, the Anglo- Egyptian Sudan, Kenya, and the country known until recently as German East Africa (now Tanganyika Territory). The Protectorate extends from one degree of south latitude to the northern limits of the navigable waters of the Victoria Nile at Nimule. It is flanked on the east by the natural boundaries of Lake Rudolf, the river Turkwel, Mount Elgon (14,200 ft.), and the Sio river, running into the north-eastern waters of Lake Victoria, whilst the outstanding features on the western side are the Nile Watershed, Lake Albert, the river Semliki, the Ruwenzori Range (16,794 ft.), and Lake Edward. -

Resettlement Action Plan RCC Reinforced Cement Concrete RMNP Rwenzori Mount National Park Iii

RESETTLEMENT AND COMPENSATION ACTION PLAN FOR THE PROPOSED SINDILA MINI HYDROPOWER PROJECT IN SINDILA SUB-COUNTY, BUNDIBUGYO DISTRICT, UGANDA. Prepared for: Butama Hydro-Electricity Company Limited Plot 41, Nakasero Road P. O. Box 9566 Kampala, Uganda Prepared by: Following a Gap Analysis against IFC Performance Standards, identified gaps plugged in and RAP Updated by: Atacama Consulting Plot 23 Gloucester Avenue, Kyambogo P.O. Box 12130 Kampala, Uganda SEPTEMBER 2014 CERTIFICATION We, the undersigned, certify that we have participated in the preparation (Butama Hydro- Electricity Company) and update (Atacama Consulting) of the Resettlement and Compensation Action Plan (RAP) for the proposed Sindila Mini Hydropower Project, to be located on River Sindila in Sindila Sub-County, Bundibugyo District, Uganda. Updating of the RAP as undertaken by Atacama Consulting was focused on addressing the gaps identified following a gap analysis, bench-marking the RAP against the requirements of the International Finance Corporation (IFC) Performance Standards (PS). The integrity of the original RAP as prepared by Butama Hydro-Electricity Company Limited remains the same. We hereby certify that the particulars provided when addressing the identified gaps as included in this updated RAP are correct and true to the best of our knowledge. Name Key role Signature RAP Preparation by: Mr. LPD Dayananda Team Leader/Sociologist Mr. Joseph Ovon Land Surveyor Mr. Alex Katikiro (BSc) Surveyor/Land Valuer Specialist Mr. Sangeetha Environmental Officer Mr. Krishantha Project Manager RAP Update (this document) by: (Atacama Consulting) Team Leader Mr. Edgar Mugisha Miss Juliana Keirungi Report Review and Quality Control Dr. Dauda Waiswa Batega RAP Specialist/Sociologist Mr. -

The Long Road to the Lubiri Attack by Yoga Adhola

The long road to the Lubiri attack by Yoga Adhola. While the Mengo establishment has been telling its story, there is another side of this story. It is the UPC story which I would like to tell. As they used to teach us in secondary school, there is always the long term causes and the immediate causes of any historic event. The long term cause of the attack lie way back in history. Professor Kiwanuka, himself a Muganda tells us Buganda became a dominant identity in the region from around 1600. He did this in an article,Kiwanuka, "The Emergence of Buganda as a dominant power in the interlacustrine region of East Africa, 1600- 1900," he published Makerere Historical Journal Volume 1 No. 1975 pages 19-32. Up to that point the Kingdom of Bunyoro-Kitara had been the most powerful nationality in the region. As a result of Bunyoro-Kitara's preoccupation with an attempted secession on her western borders, a situation, which rendered her eastern frontiers relatively undefended; and Buganda's recovery over a period of time, Buganda was able to accumulate adequate military strength with which to effectively launch an offensive against Bunyoro. (Kiwanuka, M.S.M. 1975: 19-30) Being rather limited, these advantages only enabled Buganda to recover her previously lost territory. However, in due course, from the reign of Kabaka Mawanda (1674-1704), as a result of annexing the tributary of Kooki from Bunyoro, Buganda acquired immense advantage. These territories Buganda had acquired had very important consequences: "until then Buganda had been very short of iron and weapons, and had to buy their iron from Bunyoro. -

———— “Mudo”: the Soga 'Little Red Riding Hood'

LILLIAN BUKAAYI TIBASIIMA ———— º “Mudo”: The Soga ‘Little Red Riding Hood’ ABSTRACT This essay analyses the social underpinnings of the oral tale of “Mudo,” which belongs to the Aarne–Thompson tale type 333, along with a group of similar tales that resemble the action and movement of “Little Red Riding Hood.” Basic to the exposition is Adolf Bastian’s assertion of the fundamental similarity of ideas between all social groups. In the “Mudo” story and its Ugandan variants, the victim is a solitary little girl and the villain a male ogre who devises ways of eating her; the ogre is mostly successful, although in some variants the girl manages to escape. Although these tales come from a great range of cultures and different geographical locations, and the counterpart of the ogre in the European tales is a wolf in disguise, they share elements of plot, characteriza- tion, and motif, and address similar concerns. Introduction USOGA IS PART OF EAS TERN UGANDA, surrounded by water. The B Rev. Fredrick Kisuule Kaliisa1 notes: To the west is river Kiira (Nile) marking the boundary between Buganda and Busoga. To the East is river Mpologoma separating Busoga from Bukedi. To the North are river Mpologoma and Lake Kyoga, forming the boundary be- tween Busoga and Lango. To the south, is Lake Victoria (Nalubaale). It might be the result of the geographical location of Busoga that ogre stories were composed to warn the people against impending harm if they went out alone and stayed in secluded places. Nnalongo Lukude emphasizes this: Historically, Busoga was surrounded by bodies of water and forests, it was very bushy and as a result harboured many wild animals, some of which were man-eaters. -

The Rwenzururu Movement and the Struggle for the Rwenzururu Kingdom in Uganda

DISCUSSION PAPER / 2016.01 ISSN 2294-8651 The Rwenzururu Movement and the Struggle for the Rwenzururu Kingdom in Uganda Arthur Syahuka-Muhindo Kristof Titeca Comments on this Discussion Paper are invited. Please contact the authors at: [email protected] and [email protected] While the Discussion Papers are peer- reviewed, they do not constitute publication and do not limit publication elsewhere. Copyright remains with the authors. Instituut voor Ontwikkelingsbeleid en -Beheer Institute of Development Policy and Management Institut de Politique et de Gestion du Développement Instituto de Política y Gestión del Desarrollo Postal address: Visiting address: Prinsstraat 13 Lange Sint-Annastraat 7 B-2000 Antwerpen B-2000 Antwerpen Belgium Belgium Tel: +32 (0)3 265 57 70 Fax: +32 (0)3 265 57 71 e-mail: [email protected] http://www.uantwerp.be/iob DISCUSSION PAPER / 2016.01 The Rwenzururu Movement and the Struggle for the Rwenzururu Kingdom in Uganda Arthur Syahuka-Muhindo* Kristof Titeca** March 2016 * Department of Political Science and Public Administration, Makerere University. ** Institute of Development Policy and Management (IOB), University of Antwerp. TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT 5 1. INTRODUCTION 5 2. ORIGINS OF THE RWENZURURU MOVEMENT 6 3. THE WALK-OUT FROM THE TORO RUKURATO AND THE RWENZURURU MOVEMENT 8 4. CONTINUATION OF THE RWENZURURU STRUGGLE 10 4.1. THE RWENZURURU MOVEMENT AND ARMED STRUGGLE AFTER 1982 10 4.2. THE OBR AND THE MUSEVENI REGIME 11 4.2.1. THE RWENZURURU VETERANS ASSOCIATION 13 4.2.2. THE OBR RECOGNITION COMMITTEE 14 4.3. THE OBUSINGA AND THE LOCAL POLITICAL STRUGGLE IN KASESE DISTRICT. -

Table of Contents List of Tables

TABLE OF CONTENTS 6 PROJECT IMPACTS ................................................................................................................ 138 Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 138 Summary of Impacts ................................................................................................................. 138 Impacts on Land ....................................................................................................................... 143 6.3.1 Land Requirements and Land Use Context ......................................................................... 143 Impacts on houses – Physical Displacement ........................................................................... 149 Impacts on other structures ...................................................................................................... 153 Impacts on Communal Buildings .............................................................................................. 159 Graves and Cultural Heritage Assets ....................................................................................... 160 Impacts on Crops and Economic Trees .................................................................................... 160 Impacts on Livelihood Activities – Economic Displacement ..................................................... 166 Impacts on Public Utilities/Infrastructure .................................................................................. -

Mapping Uganda's Social Impact Investment Landscape

MAPPING UGANDA’S SOCIAL IMPACT INVESTMENT LANDSCAPE Joseph Kibombo Balikuddembe | Josephine Kaleebi This research is produced as part of the Platform for Uganda Green Growth (PLUG) research series KONRAD ADENAUER STIFTUNG UGANDA ACTADE Plot. 51A Prince Charles Drive, Kololo Plot 2, Agape Close | Ntinda, P.O. Box 647, Kampala/Uganda Kigoowa on Kiwatule Road T: +256-393-262011/2 P.O.BOX, 16452, Kampala Uganda www.kas.de/Uganda T: +256 414 664 616 www. actade.org Mapping SII in Uganda – Study Report November 2019 i DISCLAIMER Copyright ©KAS2020. Process maps, project plans, investigation results, opinions and supporting documentation to this document contain proprietary confidential information some or all of which may be legally privileged and/or subject to the provisions of privacy legislation. It is intended solely for the addressee. If you are not the intended recipient, you must not read, use, disclose, copy, print or disseminate the information contained within this document. Any views expressed are those of the authors. The electronic version of this document has been scanned for viruses and all reasonable precautions have been taken to ensure that no viruses are present. The authors do not accept responsibility for any loss or damage arising from the use of this document. Please notify the authors immediately by email if this document has been wrongly addressed or delivered. In giving these opinions, the authors do not accept or assume responsibility for any other purpose or to any other person to whom this report is shown or into whose hands it may come save where expressly agreed by the prior written consent of the author This document has been prepared solely for the KAS and ACTADE. -

Environmental Decentralization and the Management of Forest Resources in Masindi District, Uganda

ENVIRONMENTAL GOVERNANCE IN AFRICA WORKING PAPERS: WP #8 COMMERCE, KINGS AND LOCAL GOVERNMENT IN UGANDA: DECENTRALIZING NATURAL RESOURCES TO CONSOLIDATE THE CENTRAL STATE by Frank Emmanuel Muhereza Febuary 2003 EDITORS World Resources Institute Jesse C. Ribot and Jeremy Lind 10 G Street, NE COPY EDITOR Washington DC 20002 Florence Daviet www.wri.org ABSTRACT This study critically explores the decentralizing of forest management powers in Uganda in order to determine the extent to which significant discretionary powers have shifted to popularly elected and downwardly accountable local governments. Effective political or democratic decentralization depends on the transfer of local discretionary powers. However, in common with other states in Africa undergoing various types of “decentralization” reforms, state interests are of supreme importance in understanding forest-management reforms. The analysis centers on the transfer of powers to manage forests in Masindi District, an area rich in natural wealth located in western Uganda. The decentralization reforms in Masindi returns forests to unelected traditional authorities, as well as privatizes limited powers to manage forest resources to licensed user-groups. However, the Forest Department was interested in transferring only those powers that increased Forest Department revenues while reducing expenditures. Only limited powers to manage forests were transferred to democratically elected and downwardly accountable local governments. Actors in local government were left in an uncertain and weak bargaining position following the transfer of powers. While privatization resulted in higher Forest Department revenues, the tradeoff was greater involvement of private sector actors in the Department’s decision making. To the dismay of the Forest Department, in the process of consolidating their new powers, private-sector user groups were able to influence decision making up to the highest levels of the forestry sector. -

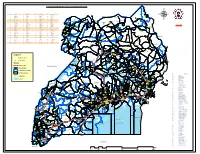

Legend " Wanseko " 159 !

CONSTITUENT MAP FOR UGANDA_ELECTORAL AREAS 2016 CONSTITUENT MAP FOR UGANDA GAZETTED ELECTORAL AREAS FOR 2016 GENERAL ELECTIONS CODE CONSTITUENCY CODE CONSTITUENCY CODE CONSTITUENCY CODE CONSTITUENCY 266 LAMWO CTY 51 TOROMA CTY 101 BULAMOGI CTY 154 ERUTR CTY NORTH 165 KOBOKO MC 52 KABERAMAIDO CTY 102 KIGULU CTY SOUTH 155 DOKOLO SOUTH CTY Pirre 1 BUSIRO CTY EST 53 SERERE CTY 103 KIGULU CTY NORTH 156 DOKOLO NORTH CTY !. Agoro 2 BUSIRO CTY NORTH 54 KASILO CTY 104 IGANGA MC 157 MOROTO CTY !. 58 3 BUSIRO CTY SOUTH 55 KACHUMBALU CTY 105 BUGWERI CTY 158 AJURI CTY SOUTH SUDAN Morungole 4 KYADDONDO CTY EST 56 BUKEDEA CTY 106 BUNYA CTY EST 159 KOLE SOUTH CTY Metuli Lotuturu !. !. Kimion 5 KYADDONDO CTY NORTH 57 DODOTH WEST CTY 107 BUNYA CTY SOUTH 160 KOLE NORTH CTY !. "57 !. 6 KIIRA MC 58 DODOTH EST CTY 108 BUNYA CTY WEST 161 OYAM CTY SOUTH Apok !. 7 EBB MC 59 TEPETH CTY 109 BUNGOKHO CTY SOUTH 162 OYAM CTY NORTH 8 MUKONO CTY SOUTH 60 MOROTO MC 110 BUNGOKHO CTY NORTH 163 KOBOKO MC 173 " 9 MUKONO CTY NORTH 61 MATHENUKO CTY 111 MBALE MC 164 VURA CTY 180 Madi Opei Loitanit Midigo Kaabong 10 NAKIFUMA CTY 62 PIAN CTY 112 KABALE MC 165 UPPER MADI CTY NIMULE Lokung Paloga !. !. µ !. "!. 11 BUIKWE CTY WEST 63 CHEKWIL CTY 113 MITYANA CTY SOUTH 166 TEREGO EST CTY Dufile "!. !. LAMWO !. KAABONG 177 YUMBE Nimule " Akilok 12 BUIKWE CTY SOUTH 64 BAMBA CTY 114 MITYANA CTY NORTH 168 ARUA MC Rumogi MOYO !. !. Oraba Ludara !. " Karenga 13 BUIKWE CTY NORTH 65 BUGHENDERA CTY 115 BUSUJJU 169 LOWER MADI CTY !. -

Centeal Chanceey of the Oedees of Knighthood

THE EDINBURGH GAZETTE, JUNE 6, 1924. 773 '.To be Officers of the'Civil Division of the said David George Goonewardena, Esq., Crown Most Excellent Order: — Proctor of Galle, Ceylon. Ernest Adams, Esq., Comptroller of Customs Selim Hanna, Esq., Assistant District Com- and -Custodian of Enemy Property, Tan- mandant of Police, Northern District, Palesr gonyika Territory. tine. Kitoyi Ajasa, Esq., Unofficial Member of the Georgiana, Mrs. Humphries, Headmistress of Legislative Council, Nigeria. the Central School Eldoret, Kenya Colony. •Charles Edward Woolhouse Bannerman, Esq., Samuel Benjamin Jones, Esq., Medical Officer Police Magistrate, Gold Coast. and Magistrate, and Coroner, Anguilla, Lieutenant-Colonel Edward Bell, M.B.E., Leeward Islands. Chief Inspector of Police, Leeward Islands. The Eeverend Father Christopher James Kirk, Captain Walter Henry Calthrop Calthrop, of the Mill Hill Mission, Uganda Protec- E.N. (retired), Master Attendant, Straits torate; in recognition of his sendees to the Settlements. Administration. Stanley York Bales, Esq., M.B.E., Custodian Miss Annie Landau, Principal of Evelina de of Enemy Property, Union of South Africa. Eothschild's School, Jerusalem; in recog- Harington Gordon Forbes, Esq., lately Secre- nition of her public services. tary of the British North Borneo Company. John Vincent Leach, Esq., Eesident Magis- .James Alfred Galizia, Esq., Superintendent trate, Parish of St. Catherine, Jamaica. of the Public Works Department, Island of Joseph Henry Levy, Esq., Chairman of the Malta. Parochial Board of St. Ann, Jamaica. •Charles Herbert Hamilton, Esq., of the Office Charles Neale, Esq., First Inspector of Civil of the General Manager of Eailways, Union Jails, Iraq. of South Africa. Sister Emma Ollerenshaw, of the Deaconess's Lieutenant-Colonel Melville David Harrel, Society of Wesleyans, Johannesburg, Union Inspector-General of Police and Com- of South Africa; in recognition of her public mandant of the Local' Forces, Barbados. -

Characterisation of the Livestock Production System and Potential for Enhancing Productivity Through Improved Feeding in Kiboga

Characterisation of the livestock production system and potential for enhancing productivity through improved feeding in Kiboga West DFBA, Kyankwanzi district, Uganda By: Jane Kugonza, Ronald Wabwire, Pius Lutakome, Ben Lukuyu and Josephine Kirui East African Dairy Development Project (EADD) The Feed Assessment Tool (FEAST) is a systematic method to assess local feed resource availability and use. It helps in the design of intervention strategies aiming to optimize feed utilization and animal production. More information and the manual can be obtained at www.ilri.org/feast FEAST is a tool in constant development and improvement. Feedback is welcome and should be directed [email protected]. The International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) is not responsible for the quality and validity of results obtained using the FEAST methodology. The Feed Assessment Tool (FEAST) was used to characterize the livestock production system and in particular feed‐related aspects in Kiboga West dairy farmers association (DFBA) of Kyankwanzi, Kyankwanzi district, Uganda. The assessment was carried out through structured group discussions and completion of short questionnaires by key farmers’ representatives1. The following are the findings of the assessment and conclusions for further action. Farming system Kyankwanzi was formerly in Kiboga district but obtained district status in 2004 and is located in the extreme part of Buganda region. The travel distance by road is approximately 220 kilometres from the capital city of Uganda, Kampala. Households in this area are composed of approximately 14 (range 6-20) members and utilise on average 15 acres of pastoral land. Table 1 shows farmers perceptions about average land sizes for different categories of farmers. -

A History of Ethnicity in the Kingdom of Buganda Since 1884

Peripheral Identities in an African State: A History of Ethnicity in the Kingdom of Buganda Since 1884 Aidan Stonehouse Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Ph.D The University of Leeds School of History September 2012 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. Acknowledgments First and foremost I would like to thank my supervisor Shane Doyle whose guidance and support have been integral to the completion of this project. I am extremely grateful for his invaluable insight and the hours spent reading and discussing the thesis. I am also indebted to Will Gould and many other members of the School of History who have ably assisted me throughout my time at the University of Leeds. Finally, I wish to thank the Arts and Humanities Research Council for the funding which enabled this research. I have also benefitted from the knowledge and assistance of a number of scholars. At Leeds, Nick Grant, and particularly Vincent Hiribarren whose enthusiasm and abilities with a map have enriched the text. In the wider Africanist community Christopher Prior, Rhiannon Stephens, and especially Kristopher Cote and Jon Earle have supported and encouraged me throughout the project. Kris and Jon, as well as Kisaka Robinson, Sebastian Albus, and Jens Diedrich also made Kampala an exciting and enjoyable place to be.