Australians of Indian Origin in Politics: Interrogating the ‘Representation Gap’ in Australia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Disporia of Borders: Hindu-Sikh Transnationals in the Diaspora Purushottama Bilimoria1,2

Bilimoria International Journal of Dharma Studies (2017) 5:17 International Journal of DOI 10.1186/s40613-017-0048-x Dharma Studies RESEARCH Open Access The disporia of borders: Hindu-Sikh transnationals in the diaspora Purushottama Bilimoria1,2 Correspondence: Abstract [email protected] 1Center for Dharma Studies, Graduate Theological Union, This paper offers a set of nuanced narratives and a theoretically-informed report on Berkeley, CA, USA what is the driving force and motivation behind the movement of Hindus and Sikhs 2School of Historical and from one continent to another (apart from their earlier movement out of the Philosophical Studies, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia subcontinent to distant shores). What leads them to leave one diasporic location for another location? In this sense they are also ‘twice-migrants’. Here I investigate the extent and nature of the transnational movement of diasporic Hindus and Sikhs crossing borders into the U.S. and Australia – the new dharmic sites – and how they have tackled the question of the transmission of their respective dharmas within their own communities, particularly to the younger generation. Two case studies will be presented: one from Hindus and Sikhs in Australia; the other from California (temples and gurdwaras in Silicon Valley and Bay Area). Keywords: Indian diaspora, Hindus, Sikhs, Australia, India, Transnationalism, Diaspoetics, Adaptation, Globalization, Hybridity, Deterritorialization, Appadurai, Bhabha, Mishra Part I In keeping with the theme of Experimental Dharmas this article maps the contours of dharma as it crosses borders and distant seas: what happens to dharma and the dharmic experience in the new 'experiments of life' a migrant community might choose to or be forced to undertake? One wishes to ask and develop a hermeneutic for how the dharma traditions are reconfigured, hybridized and developed to cope and deal with the changed context, circumstances and ambience. -

Australian Foreign Policy the Hon Julie Bishop MP Senator the Hon

Australian Foreign Policy The Hon Julie Bishop MP Minister for Foreign Affairs Julie Bishop is Deputy Leader of the Liberal Party. She was sworn in as Australia’s first female foreign minister in September 2013 following four years as Shadow Minister for Foreign Affairs and Trade. She previously served in the Howard Government as Minister for Education, Science and Training, as Minister Assisting the Prime Minister for Women’s Issues and as Minister for Ageing. Prior to entering Parliament as the Member for Curtin in 1998, she was a commercial litigation lawyer at Clayton Utz, becoming a partner and managing partner. Senator The Hon Penny Wong Shadow Minister for Foreign Affairs Penny Wong is a Labor Senator for South Australia and Leader of the Opposition in the Senate, a position she has held since 2013. Senator Wong previously served as Minister for Climate Change and Water, before her appointment to the Finance and Deregulation portfolio. Born in Malaysia, her family moved to Australia in 1976. She studied arts and law at the University of Adelaide. Prior to entering federal politics, she worked for a trade union and as a Ministerial adviser to the NSW Labor government. The Hon Kim Beazley AC FAIIA National President, Australian Institute of International Affairs During 37 years in politics, Kim Beazley served as Deputy Prime Minister, Leader of the ALP and Leader of the Opposition. He has been Minister for Defence; Finance; Transport and Communications; Employment, Education and Training; Aviation; and Special Minister of State. After retiring from politics, he was Winthrop Professor at UWA and Chancellor of the ANU. -

Social Democracy and the Rudd Labor Government in Australia

Internationale Politikanalyse International Policy Analysis Andrew Scott Social Democracy and the Rudd Labor Government in Australia As the Rudd Labor Party Government in Australia celebrates two years in office following the Party’s many years in opposition, it is in a strong position. However, it needs to more clearly outline its social democratic ambitions in order to break free from the policies of the former right-wing government, from three decades of neo-liberal intellectual dominance and from association with the ineffectual policy approach of British Labour’s »Third Way«. This can be done with a greater and more sustained commitment to improve industrial relations in favour of working families, including by fur- ther expanding paid parental leave. There also need to be further increases in public investment, including in all forms of education, and policy action to broaden the nation’s economic base by rebuilding manufacturing in- dustry. Other priorities should be to better prevent and alleviate the plight of the unemployed, and to tackle the inadequate taxation presently paid by the wealthy. Australia needs now to look beyond the English-speaking world to en- visage social democratic job creation programs in community services, and to greatly reduce child poverty. Australia also needs better planning for the major cities, where the population is growing most. Consistent with the wish for a greater role as a medium-sized power in the world, Aus- tralia’s Labor Government needs to take more actions towards a humani- tarian -

The Australian Labor Party Response

2 May 2019 Arthur Moses SC President Law Council of Australia GPO Box 1989 CANBERRA ACT 2601 [email protected] Dear Mr Moses Thank you for writing to the Australian Labor Party (ALP), providing your 2019 Federal Election Call to Parties roadmap and requesting our response to the issues raised. We commend the Law Council of Australia on the comprehensive and thoughtful nature of the Call to Parties. Please find below the ALP’s response under each of the broad themes you have identified. This is not all inclusive, and Labor looks forward to continuing to work closely with the Law Council on law reform. Labor has long considered many of the issues identified in the Call to Parties, and we have given attention to many in our National Platform, and in our election commitments to date, the detail of which are incorporated into this response. Access to Justice Labor believes that for Australia to remain a fair and democratic nation, justice must be accessible to all Australians, rather than only to wealthy individuals and companies who can afford to hire lawyers. Labor believes that all Australians, not just the wealthy, should have the right to a fair go under the law. Providing access to justice for all Australians has been a Labor priority for over a generation, when the Whitlam Government established Legal Aid. Since that time, Labor has championed and strengthened the legal assistance sector. Our priority is to strengthen the legal assistance sector, ensuring that all Australians, not just the wealthy, have access to justice. Our policies in this area include: • Expanding the financial rights legal assistance sector from 40 lawyers to 240 lawyers across Australia, using $120 million from the Banking Fairness Fund. -

Liberal Nationals Released a Plan

COVID-19 RESPONSE May 2020 michaelobrien.com.au COVID-19 RESPONSE Dear fellow Victorians, By working with the State and Federal Governments, we have all achieved an extraordinary outcome in supressing COVID-19 that makes Victoria – and Australia - the envy of the world. We appreciate everyone who has contributed to this achievement, especially our essential workers. You have our sincere thanks. This achievement, however, has come at a significant cost to our local economy, our community and to our way of life. With COVID-19 now apparently under a measure of control, it is urgent that the Andrews Labor Government puts in place a clear plan that enables us to take back our Michael O’Brien MP lives and rebuild our local communities. Liberal Leader Many hard lessons have been learnt from the virus outbreak; we now need to take action to deal with these shortcomings, such as our relative lack of local manufacturing capacity. The Liberals and Nationals have worked constructively during the virus pandemic to provide positive suggestions, and to hold the Andrews Government to account for its actions. In that same constructive manner we have prepared this Plan: our positive suggestions about what we believe should be the key priorities for the Government in the recovery phase. This is not a plan for the next election; Victorians can’t afford to wait that long. This is our Plan for immediate action by the Andrews Labor Government so that Victoria can rebuild from the damage done by COVID-19 to our jobs, our communities and our lives. These suggestions are necessarily bold and ambitious, because we don’t believe that business as usual is going to be enough to secure our recovery. -

Legislative Council- PROOF Page 1

Tuesday, 15 October 2019 Legislative Council- PROOF Page 1 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL Tuesday, 15 October 2019 The PRESIDENT (The Hon. John George Ajaka) took the chair at 14:30. The PRESIDENT read the prayers and acknowledged the Gadigal clan of the Eora nation and its elders and thanked them for their custodianship of this land. Governor ADMINISTRATION OF THE GOVERNMENT The PRESIDENT: I report receipt of a message regarding the administration of the Government. Bills ABORTION LAW REFORM BILL 2019 Assent The PRESIDENT: I report receipt of message from the Governor notifying Her Excellency's assent to the bill. REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH CARE REFORM BILL 2019 Protest The PRESIDENT: I report receipt of the following communication from the Official Secretary to the Governor of New South Wales: GOVERNMENT HOUSE SYDNEY Wednesday, 2 October, 2019 The Clerk of the Parliaments Dear Mr Blunt, I write at Her Excellency's command, to acknowledge receipt of the Protest made on 26 September 2019, under Standing Order 161 of the Legislative Council, against the Bill introduced as the "Reproductive Health Care Reform Bill 2019" that was amended so as to change the title to the "Abortion Law Reform Bill 2019'" by the following honourable members of the Legislative Council, namely: The Hon. Rodney Roberts, MLC The Hon. Mark Banasiak, MLC The Hon. Louis Amato, MLC The Hon. Courtney Houssos, MLC The Hon. Gregory Donnelly, MLC The Hon. Reverend Frederick Nile, MLC The Hon. Shaoquett Moselmane, MLC The Hon. Robert Borsak, MLC The Hon. Matthew Mason-Cox, MLC The Hon. Mark Latham, MLC I advise that Her Excellency the Governor notes the protest by the honourable members. -

Still Anti-Asian? Anti-Chinese? One Nation Policies on Asian Immigration and Multiculturalism

Still Anti-Asian? Anti-Chinese? One Nation policies on Asian immigration and multiculturalism 仍然反亚裔?反华裔? 一国党针对亚裔移民和多元文化 的政策 Is Pauline Hanson’s One Nation party anti-Asian? Just how much has One Nation changed since Pauline Hanson first sat in the Australian Parliament two decades ago? This report reviews One Nation’s statements of the 1990s and the current policies of the party. It concludes that One Nation’s broad policies on immigration and multiculturalism remain essentially unchanged. Anti-Asian sentiments remain at One Nation’s core. Continuity in One Nation policy is reinforced by the party’s connections with anti-Asian immigration campaigners from the extreme right of Australian politics. Anti-Chinese thinking is a persistent sub-text in One Nation’s thinking and policy positions. The possibility that One Nation will in the future turn its attacks on Australia's Chinese communities cannot be dismissed. 宝林·韩森的一国党是否反亚裔?自从宝林·韩森二十年前首次当选澳大利亚 议会议员以来,一国党改变了多少? 本报告回顾了一国党在二十世纪九十年代的声明以及该党的现行政策。报告 得出的结论显示,一国党关于移民和多元文化的广泛政策基本保持不变。反 亚裔情绪仍然居于一国党的核心。通过与来自澳大利亚极右翼政坛的反亚裔 移民竞选人的联系,一国党的政策连续性得以加强。反华裔思想是一国党思 想和政策立场的一个持久不变的潜台词。无法排除一国党未来攻击澳大利亚 华人社区的可能性。 Report Philip Dorling May 2017 ABOUT THE AUSTRALIA INSTITUTE The Australia Institute is an independent public policy think tank based in Canberra. It is funded by donations from philanthropic trusts and individuals and commissioned research. Since its launch in 1994, the Institute has carried out highly influential research on a broad range of economic, social and environmental issues. OUR PHILOSOPHY As we begin the 21st century, new dilemmas confront our society and our planet. Unprecedented levels of consumption co-exist with extreme poverty. Through new technology we are more connected than we have ever been, yet civic engagement is declining. -

2010 Victorian State Election Summary of Results

2010 VICTORIAN STATE ELECTION 27 November 2010 SUMMARY OF RESULTS Introduction ............................................................................................................. 1 Legislative Assembly Results Summary of Results.......................................................................................... 3 Detailed Results by District ............................................................................... 8 Summary of Two-Party Preferred Result ........................................................ 24 Regional Summaries....................................................................................... 30 By-elections and Casual Vacancies ................................................................ 34 Legislative Council Results Summary of Results........................................................................................ 35 Incidence of Ticket Voting ............................................................................... 38 Eastern Metropolitan Region .......................................................................... 39 Eastern Victoria Region.................................................................................. 42 Northern Metropolitan Region ........................................................................ 44 Northern Victoria Region ................................................................................ 48 South Eastern Metropolitan Region ............................................................... 51 Southern Metropolitan Region ....................................................................... -

David Bartlett, MP PREMIER Dear Premier in Accordance with The

David Bartlett, MP PREMIER Dear Premier In accordance with the requirements of Section 36(1) of the State Service Act 2000 and Section 27 of the Financial Management and Audit Act 1990, I enclose for presentation to Parliament, the 2007-08 Annual Report of the Department of Premier and Cabinet. Yours sincerely Rhys Edwards Secretary 17 October 2008 The Department of Premier and Cabinet (DPAC) is a central agency of the Tasmanian State Government. The Department is responsible to the Premier and the Minister for Local Government as portfolio ministers, and also provides support to the Parliamentary Secretary and other members of Cabinet. The Department provides a broad range of services to the Cabinet, other members of Parliament, Government agencies and the community. The Department works closely with the public sector, the community, local government, the Australian Government and other state and territory governments. The Department also provides administration support to the State Service Commissioner and the Tasmania Together Progress Board, each of which is separately accountable and reports directly to Parliament. Department of Premier and Cabinet Annual Report 2007-08 2 Content Secretary’s Report 5 Departmental Overview 7 Governance 8 Activity Report 2007-08 12 Output Group 1 - Support for Executive Decision Making 13 Output 1.1: Strategic Policy and Advice 14 Output 1.2: Climate Change 18 Output 1.3: Social Inclusion 21 Output Group 2 - Government Processes and Services 23 Output 2.1: Management of Executive Government Processes -

Alan Tudge's Contempt Seems to Know No Bounds. Why Is He Still a Minister?

Alan Tudge’s contempt seems to know no bounds. Why is he still a minister? Scott Morrison has not said a word about why he is maintaining in his cabinet a minister so disgraced. That, too, is a disgrace. MICHAEL BRADLEY OCT 08, 2020 It is fair to conclude that acting Immigration Minister Alan Tudge has a deep contempt for the law. What else could motivate him, when the Federal Court has just declared in explicit terms that he committed one form of contempt (wilful disobedience of court orders), to just double down on what the court may see as another — the one it calls “scandalising the court”? Bear in mind that Tudge’s original contempt was a triple: he refused to comply with an order by the Administrative Appeals Tribunal (AAT) to release a man from immigration detention, and then ignored orders by two Federal Court judges before finally relenting after five days of maintaining an imprisonment that was completely illegal. Justice Geoffrey Flick of the Federal Court called Tudge’s conduct “disgraceful” and “criminal”, noting that it exposed him to “civil and potentially criminal sanctions, not limited to a proceeding for contempt”. That was a couple of weeks ago; Tudge has not resigned or been sacked. Instead he has been layering on the contempt, telling the ABC that Flick’s findings were “comments by a particular judge, which I strongly reject … We’re looking at our appeal rights, presently.” This seems to be the law according to Tudge: sort of an opt-in thing. As his lawyers had unsuccessfully argued to several judges, his reason for ignoring the AAT’s original order was that he disagreed with it, intended to appeal it and therefore didn’t really need to comply with it. -

Digital Edition

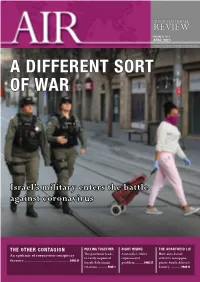

AUSTRALIA/ISRAEL REVIEW VOLUME 45 No. 4 APRIL 2020 AUSTRALIA/ISRAEL & JEWISH AFFAIRS COUNCIL A DIFFERENT SORT OF WAR Israel’s military enters the battle against coronavirus THE OTHER CONTAGION PULLING TOGETHER RIGHT RISING THE APARTHEID LIE An epidemic of coronavirus conspiracy The pandemic leads Australia’s white How anti-Israel to vastly improved supremacist activists misappro- theories ............................................... PAGE 21 Israeli-Palestinian problem ........PAGE 27 priate South Africa’s relations .......... PAGE 7 history ........... PAGE 31 WITH COMPLIMENTS NAME OF SECTION L1 26 BEATTY AVENUE ARMADALE VIC 3143 TEL: (03) 9661 8250 FAX: (03) 9661 8257 WITH COMPLIMENTS 2 AIR – April 2020 AUSTRALIA/ISRAEL VOLUME 45 No. 4 REVIEW APRIL 2020 EDITOR’S NOTE NAME OF SECTION his AIR edition focuses on the Israeli response to the extraordinary global coronavirus ON THE COVER Tpandemic – with a view to what other nations, such as Australia, can learn from the Israeli Border Police patrol Israeli experience. the streets of Jerusalem, 25 The cover story is a detailed look, by security journalist Alex Fishman, at how the IDF March 2020. Israeli authori- has been mobilised to play a part in Israel’s COVID-19 response – even while preparing ties have tightened citizens’ to meet external threats as well. In addition, Amotz Asa-El provides both a timeline of movement restrictions to Israeli measures to meet the coronavirus crisis, and a look at how Israel’s ongoing politi- prevent the spread of the coronavirus that causes the cal standoff has continued despite it. Plus, military reporter Anna Ahronheim looks at the COVID-19 disease. (Photo: Abir Sultan/AAP) cooperation the emergency has sparked between Israel and the Palestinians. -

Spotlight on Democracy ANNUAL REPORT 2018–2019 About the VEC

Spotlight on Democracy ANNUAL REPORT 2018–2019 About the VEC Our vision Our history and functions All Victorians actively participating in their democracy. Elections for the Victorian Parliament began when Victoria achieved independence from New South Wales in 1851. In 1910, Victoria’s first Chief Electoral Inspector was Our purpose appointed to head the new State Electoral Office. To deliver high quality, accessible electoral services with The State Electoral Office existed as part of a public innovation, integrity and independence. service department for 70 years. However, it became increasingly clear that it was inappropriate for the Our values conduct of elections to be subject to ministerial direction. On 1 January 1989, legislation established the • Independence: acting with impartiality and integrity independent statutory office of Electoral Commissioner • Accountability: transparent reporting and effective who was to report to Parliament instead of a Minister. stewardship of resources In 1995, the State Electoral Office was renamed the • Innovation: shaping our future through creativity Victorian Electoral Commission. and leadership The VEC’s functions and operations are governed by six • Respect: consideration of self, others and main pieces of legislation: the environment • Electoral Act 2002 - establishes the VEC as an • Collaboration: working as a team with partners independent statutory authority, sets out the and communities functions and powers of the VEC and prescribes processes for State elections • Constitution Act 1975 - sets out who is entitled to Our people and partners enrol as an elector, who is entitled to be elected to The Victorian Electoral Commission (VEC) has a core staff Parliament, and the size and term of Parliament of dedicated and highly skilled people whose specialised • Financial Management Act 1994 - governs the way the knowledge ensures the success of its operations.