Women Who Abuse”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Bestseller Experiment-Writers

!1 Welcome, brave writer… You’ve heard the podcasts, you’ve signed up to the mailing list, you’ve defeated the three-headed dragon at the gates of development hell (entirely optional… most people skip that part) and now you have access to the exclusive Writers’ Vault of Gold, the written repository of the best gems of wisdom from our wonderful guests on the Bestseller Experiment podcast. This book is our gift to you, a magic sword on your hero’s journey, as you too slay your demons of procrastination and goblins of, er, writer’s block* Whatever. It’s a free book full of writing tips from industry experts. Free! And it will continue to update and expand throughout the fifty-two weeks of the Bestseller Experiment challenge. Look out for future weekly summaries by email. You can download the latest version of the eBook at any time — completely free! — using the link on the Writers’ Vault of Gold email when you first subscribed. And if you’ve found this book useful and would like to contribute to the running of the podcast and this project, please visit our page at patreon.com/bestsellerexperiment !2 As supporters, we’ll include your name in a special acknowledgments section at the back of this book. So enjoy these top tips, take what you need from the vault to enrich your story and join us in the Bestseller Experiment Challenge to tell the world your story. *This metaphor is rapidly running out of steam. !3 About the Marks London-based author and screenwriter Mark Stay co-wrote the screenplay for Robot Overlords which became a movie with Sir Ben Kingsley and Gillian Anderson, and premiered at the 58th London Film Festival. -

29 September

“I know YOU shot him,Mick!” 2 CANCER AGONY! Chas & Paddy’s newborn daughter slips away... Sinead’s secret battle WHILE SALLY’S MARRIED AWAY... TIM & GINA KISS OF ATLAST! WILL PLAY! DEATH 39 FOR KEANU? 9 770966 849166 Issue 39 • 29 Sep – 5 Oct 2018 over the page, this is a highly charged episode, which even Yo u r s t a r s manages a few surprises ometimes it week’s Emmerdale. Paddy while the emotional truth plays this week! seems as if and Chas take in the joy out. As parents themselves, the soaps of their beautiful baby girl, it’s a hell of an ask for Dom 4 are all thrills and before watching her slip and Lucy to go to the places spills – affairs, they had to for this kidnappingsd episode, but both annd explosions “Dom and Lucy have have been totally haappen almost been totally dedicated” dedicated to this plot evvery second from the word go. episode. But once away – a tragic fact they I feel there may be some inn a while, they hit have spent months trying awards coming their way youy between the to come to terms with. after this week, and we eyes in a rather As Lucy Pargeter and deserved they’ll be. Lucy Pargeter different way, which Dominic Brunt, who play Steven Murphy, Editor “It’s a mixture of blind haappens in this Chas and Paddy, reveal [email protected] panic and excitement and anticipation” The BIG 6 16 stories... Coronation Street 8 Sinead has a cancer scare 20 Ryan is jailed for Cormac’s death 26 Carla & Johnny set a honey trap Put me a monkey 27 Ali urges Jude to come clean on that Lee Ryan being 28 Abi stays away from Tracy’s hen do first out of Strictly. -

Superman Iv Fx I Bowie ■ Ian Rush ■ Big Country ■ Death Stars ■ the Stranglers ■ Skiing Holidays

Wfi,. • '/: ?/■ As'-'i-: ■ SUPERMAN IV FX I BOWIE ■ IAN RUSH ■ BIG COUNTRY ■ DEATH STARS ■ THE STRANGLERS ■ SKIING HOLIDAYS ■ WINTER COATS ■ LP/VIDEO/BOOK REVIEWS ■ JOYSTICK ROUND—UP ■ WIN A VID! ■ WIN A TOMATO! ■ WIN A CURRY! ■ REVIEW OF THE YEAR T¥m IS LM WELCOME to this 80-page A NEWSFIELD PUBLICATION first issue of LMt, You've probably been JANUARY 1987 Joint Publishers Franco Frev. Oliver Published by Leisure Monthly Ltd reading Newsfield compu Frev Roaei Kean foi Newsfield Publications Ltd ter mags for some time Editor Rocrei Kean now, but you’ll find LM is Deputy Editor Paul Strange r 1986 Newsfield Publications quite different. Different, London Editor David Cheat Limited Features Editor Curtis Hutchinson because it has an aggres Sub-Editor Barnabv Paqe sively personal approach; Staff Writers Sue Dando Richard REVIEWS different because it is set Lowe IJoyd Mangram Simon Poultei Editorial Assistants Sally Newman ting out to cover the widest Mary Moms 39 Hot videos imaginable range of life's Art Director Oliver Frey aspects. Assistant Art Editor Gordon Drure (Annhilator, Back To The Future, Under LM’s strength lies in the Production Controller David The Cherry Moon, Rocky IV, hot platters Western outlook and attitude of its Pet Shop Boys, Paul Young, Spandau, Production Matthew Uffindell Mark writers, who have come China Crisis, The Stranglers, Billy, etc), and Kendnck Jonathan Rignall Nick together because they Orchard some great golden turkeys. Strong stuffing. share similar views on life. Group Advertisement Manager Roger Bennett However, sharing a gen National Sales Executive Barbara eral view is one thing — Gilliland REGULARS agreeing on the detail is Advertising Assistant Nick Wild another, especially when Circulations Manager Thm Hamilton Subscription* Manager Dcmsp 8 UPFRONT the specific covers such a Robert? generality of subject mate Editorial Offices Where it's at, the lowdown, and new bits. -

Yates, C.(2010)RE2(2).Pdf

University of East London Institutional Repository: http://roar.uel.ac.uk This paper is made available online in accordance with publisher policies. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item and our policy information available from the repository home page for further information. To see the final version of this paper please visit the publisher’s website. Author(s): Yates, Candida Title: Turning to Flirting: Politics and the Pleasures of Boris Johnson Year of publication: 2010 Citation: Yates, C. (2010) ‘Turning to Flirting: Politics and the Pleasures of Boris Johnson’ Rising East, Vol 2 Series 1 No. 2. Link to published version: http://www.uel.ac.uk/risingeast/essays/2010-02-17.htm Candida Yates Submission to Rising East Journal (See: Rising East, Vol. 2, Series 1, No.2, Feb 17, 2010) ‘Ping Pong’s Coming Home’; Political flirtation and the Pleasures of Boris Johnson (Not to be quoted without Author’s permission) ‘Ping pong was re-invented on the dining tables of England’ (Boris Johnson, the Chinese Olympic games hand-over party, 2009). Boris Johnson’s now notorious ‘ping pong’s coming home’ speech remains extremely popular on YouTube, with 163,358 hits to date - presumably from Johnson’s fans, whose postings can be found in various dedicated websites and newspaper columns in digital and print media.i In that Olympic hand-over speech, Johnson performed his usual shtick to great effect, and as sports journalist Matt Dickinson (2008) reported, he resembled a rather untidy, portly ‘sixth former’ from an earlier age, escaped from the pages of The Dandy. -

Eastenders Goes Live

explore.gateway.bbc.co.uk/ariel THE BBC NEWSPAPER 09·02·10 Week 6 PHOTOGRAPH: ADRIAN WEINBRECHT PHOTO COMPOSITION: JAMIE CURREY a Happy birthday? EastEnders goes live - p8-9 216 News aa 00·00·08 09·02·10 a Collaboration and better use of social media will alter ways of working Horrocks tells journalists Room 2316, White City 201 Wood Lane, London W12 7TS 020 8008 4222 Editor change is coming, embrace it Candida Watson 02-84222 Deputy editor by Kate Arkless Gray Cathy Loughran 02-27360 Chief writer PETER HORROCKS, DIRECTOR of Global News, Sally Hillier 02-26877 has issued a challenge to BBC journalists – em- Features editor brace change, accept collaboration and make Clare Bolt 02-27445 use of new information sources like social Broadcast Journalists media, or re-consider what you are doing. Claire Barrett 02-27368 Delivering the keynote speech at the Global Adam Bambury 02-27410 News Creative Network ‘Fit for the Future’ ses- AV Manager sion in Bush House, (run in conjunction with Peter Roach 02-24622 the College of Journalism) Horrocks said BBC Art editor journalism needed to be more collaborative and make better use of the resources offered by Ken Sinyard 02-84229 sites like Twitter. He said there must be a cul- Digital Design Executive tural shift to take account of the way technol- David Murray 02-27380 ogy is changing both the job and the way audi- ences relate to output. He drew on his experiences as a former News- night editor to highlight the contrast between Guest contributors this week the programme-based mindset, and his vision of a more open and sharing culture in future. -

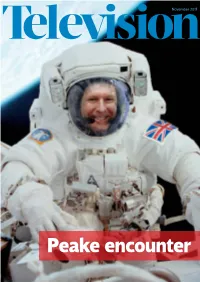

Peake Encounter BBRITAINN’S NEXTT TOPM MODEL

November 2017 Peake encounter BBRITAINN’S NEXTT TOPM MODEL A UK PRODUCTION FROM Journal of The Royal Television Society November 2017 l Volume 54/10 From the CEO I think I can safely say knowledgeable and experienced in television’s infatuation with what is that everyone who negotiating Premier League rights loosely called “swords and sandals” attended our recent than any other media executive in the drama. I love these shows and am joint event with the UK, and possibly in the world. I was looking forward to the upcoming, IET came away buzz- thrilled when he agreed to write an eight-part Troy: Fall of a City, made for ing. Astronaut Tim analysis for Television, setting out some the BBC and Netflix, as well as Sky’s Peake was a brilliant likely scenarios of how Sky might Britannia and the returning Vikings. guest, full of charm and endlessly react to a bid from one of the tech Also inside, don’t miss Simon Bucks, informative. I want to thank him for giants. This is essential reading for Our Friend in the Forces. The former finding the time to speak to us in the anyone interested in what is at stake Sky News executive explains what it truly splendid setting of the audito- when the bidding begins in earnest. is like to leave Civvy Street and to rium at the IET. He is a true star. Of late, our screens have been broadcast from the front line. Thanks, too, to BBC Worldwide CEO blessed by some brilliant factual TV, Google is never far away from Tim Davie for hosting the evening and not least Bake Off and the amazing Blue the headlines, so I am delighted that to our producer Helen Scott. -

A Critical Social Semiotic Study of the Word Chav in British Written Public Discourse, 2004-8

A CRITICAL SOCIAL SEMIOTIC STUDY OF THE WORD CHAV IN BRITISH WRITTEN PUBLIC DISCOURSE, 2004-8 by JOE BENNETT A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of PhD in English. Department of English School of EDACS University of Birmingham March 2011 AHRC award no. 2007/134908 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract This thesis explores the use of the word chav in written discourse in Britain published between 2004 and 2008. Taking a critical social semiotic approach, it discusses how chav as a semiotic resource contributes to particular ways of using language to represent the world – Discourses – and to particular ways of using language to act on the world – Genres – suggesting that, though the word is far from homogenous in its use, it is consistently used to identify the public differences of Britain as a class society in terms of personal dispositions and choices, and in taking an ironic, stereotyped stance towards such differences. It is suggested that these tendencies can be viewed as ideological, as contributing to social domination and inequality. -

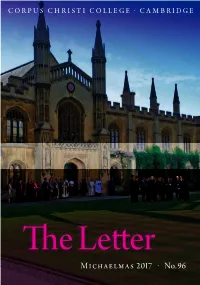

Michaelmas 2017 · No. 96

CORPUS CHRISTI COLLEGE · CAMBRIDGE The Letter Michaelmas 2017 · No. 96 Cover photo: The Chapel Choir sing motets on New Court Lawn, Corpus Christi Day, June 2017. Photo: Elizabeth Abusleme. The Letter (formerly Letter of the Corpus Association) Michaelmas 2017 No. 96 Corpus Christi College Cambridge Corpus Christi College The Letter michaelmas 2017 Editors The Master Paul Davies Brian Hazleman Assisted by John Sargant Contact The Editors The Letter Corpus Christi College Cambridge cb2 1rh [email protected] Production Designed by Dale Tomlinson ([email protected]) Typeset in Arno Pro and Cronos Pro Printed by Lavenham Press, Lavenham, Suffolk on 90gsm Sovereign Silk (Forest Stewardship Council certified) The Letter on the web http://www.corpus.cam.ac.uk/about-us/publications/the-corpus-letter News and Contributions Members of the College are asked to send to the Editors any news of themselves, or of each other, to be included in The Letter, and to send prompt notification of any change in their permanent address. Cover photo: The Chapel Choir sing motets on New Court Lawn, Corpus Christi Day, June 2017. Photo: Elizabeth Abusleme. 2 michaelmas 2017 The Letter Corpus Christi College Contents The Society Page 5 Domus 8 The College Year Senior Tutor’s report 11 Leckhampton life 12 Bursary matters 13 College staff 14 The Chapel 15 Music 17 The Libraries 19 Development and Communications 20 The Chapel Choir tour to Singapore, New Zealand and Hong Kong 22 Features, addresses and a recollection The Ahmed Lecture 24 Commemoration -

The Recording and Broadcasting Team Work Continually to Improve the Accuracy of the Recording and Session Information We Hold

The Recording and Broadcasting Team work continually to improve the accuracy of the recording and session information we hold. We believe we may have incomplete performer line-up information for the below recordings. If you have line-up information you can provide on the below titles, please contact us at: [email protected] Held Rec ID Recording Type Artist / Programme Track Title Reference / Notes Monies 7 Television Popstars Theme Tune 8 Television The National Lottery Theme Tune Yes 40 Television The Singing Detective Series Yes 124 Live Gary Barlow feat. James Corden Pray Live 223 Television Parkinson Sammy Davis Jnr "Candy Man" 225 Television Meet Sammy Davis Jnr "Be Myself" & "Mr Wonderful (intro) 253 Commercial Audio Shirley Bassey Don't Cry For Me Argentina (1993) 268 Television Gordon Franks Ensemble Citizen James (Series) 517 Television A Tale of Two Cities Series Chris Gradwell 542 Television Pickwick Papers Series Alan Merrick Yes 588 Television The Pointer Sisters Slow Hand Russell Harty Show 614 Television University Challenge Theme Tune (Original) College Boy 617 Television Treasure Hunt Theme Tune Peak Performance 619 Television Three-Two-One Theme Tune 'Speedy Gonzalez' Variety 620 Television Three-Two-One Performance 621 Television Family Fortunes Theme Tune (1980-85) 623 Television The Golden Shot Theme Tune 638 BBC Bing Crosby The Final Chapter Don't Push Your Foot on the 731 Television Kate Bush from 'Sounds Like Friday' Heartbreak 755 Television One Man & His Dog Theme Tune BBC 776 Commercial Audio The Little Match -

THE WORLD ACCORDING to CLARKSON Jeremy Clarkson Made His Name Presenting a Poky Motoring Programme on BBC2 Called Top Gear

PENGUIN BOOKS THE WORLD ACCORDING TO CLARKSON Jeremy Clarkson made his name presenting a poky motoring programme on BBC2 called Top Gear. He left to forge a career in other directions but made a complete hash of everything and ended up back on Top Gear again. He lives with his wife, Francie, and three children in Oxfordshire. Despite this, he has a clean driving licence. The World According to Clarkson JEREMY CLARKSON PENGUIN BOOKS PENGUIN BOOKS Published by the Penguin Group Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA Penguin Group (Canada), 10 Alcorn Avenue, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4V 3B2 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.) Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd) Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd) Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi – 110 017, India Penguin Group (NZ), cnr Airborne and Rosedale Roads, Albany, Auckland 1310, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd) Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank 2196, South Africa Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England www.penguin.com These articles first appeared in the Sunday Times between 2001 and 2003 This collection first published by Michael Joseph 2004 Published in Penguin Books 2005 -

University of Southampton Research Repository

University of Southampton Research Repository Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis and, where applicable, any accompanying data are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis and the accompanying data cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content of the thesis and accompanying research data (where applicable) must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder/s. When referring to this thesis and any accompanying data, full bibliographic details must be given, e.g. Thesis: Author (Year of Submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University Faculty or School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. Data: Author (Year) Title. URI [dataset] University of Southampton Faculty of Arts and Humanities School of Humanities East End Jewish Involvement in Unity Theatre and Post-War British Entertainment: A Study of Second Generation Identity by Isabelle Seddon MRes Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy October 2018 University of Southampton Abstract Faculty of Arts and Humanities School of Humanities Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy East End Jewish Involvement in Unity Theatre and Post-War British Entertainment: A Study of Second Generation Identity by Isabelle Seddon This thesis is the first study of second generation Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe who took part in left-wing political theatre groups in the first half of the twentieth century. -

Much of the Written Material on the Media Coverage of the Second

‘A Dismal and Dangerous Occupation’ An investigation into the discourses in the television news and documentary coverage of the British military in Iraq from 2004-2009, examining how the coverage plays out in the specific genres Janet Harris School of Journalism, Media and Cultural Studies Cardiff University This thesis is submitted to Cardiff University in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2012 1 Abstract This study looks at the dominant discourses in the news and documentary coverage of the British military in the occupation of Iraq. It is in these discourses that the justification for the war and occupation rests and in this justification lies the interpretation of the function, efficacy and cost of the military. To do this I have examined the genres of news, news and current affairs documentaries and traditional documentaries to see how these genres favour certain discourses and circumstances which allow certain questions to be asked, but resist others. Evidence from the Chilcot Inquiry is used to illustrate what themes and questions have been silenced in the television coverage. The dominant discourse of coverage is that of the suffering, heroic soldier, taking part in a ‘humanitarian’ war, although what this actually entails is not examined in depth. In this study it is the news and NCA documentaries and not traditional documentaries which provide a deeper context, a wider range of voices, and a more critical view of the military’s role and strategy in Iraq. The nature of the occupation is confused, the junior nature of the British military’s relationship with the Americans is not explained, the financial cost of the occupation is ignored in the elision with the moral cost of death, and the political and governing role of a military occupation is not considered.