A Case of Self Reliant Irrigation Practice in Gaya

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Village & Townwise Primary Census Abstract, Yamunanagar, Part XII A

CENSUS OF INDIA 1991 SERIES -8 HARYANA DISTRICT CEN.SUS HANDBOOK PART XII - A & B VILLAGE & TOWN DIRECTORY VILLAGE &TOWNWISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT DISTRICT YAMUNANAGAR Direqtor of Census Operations Haryana Published by : The Government of Haryana. 1995 ir=~~~==~==~==~====~==~====~~~l HARYANA DISTRICT YAMUNANAGAR t, :~ Km 5E3:::a::E0i:::=::::i====310==::::1i:5==~20. Km C.O.BLOCKS A SADAURA B BILASPUR C RADAUR o JAGADHRI E CHHACHHRAULI C.D.BLOCK BOUNDARY EXCLUDES STATUTORY TOWN (S) BOUNDARIES ARE UPDATED UPTO 1.1.1990 W. R.C. WORKSHOP RAILWAY COLONY DISTRICT YAMUNANAGAR CHANGE IN JURI50lC TION 1981-91 KmlO 0 10 Km L__.j___l BOUNDARY, STATE ... .. .. .. _ _ _ DISTRICT _ TAHSIL C D. BLOCK·:' .. HEADQUARTERS: DISTRICT; TAHSIL; e.D. BLOCK @:©:O STATE HIGHWAY.... SH6 IMPORT ANi MEiALLED ROAD RAILWAY LINE WITH STATION. BROAD GAUGE RS RIVER AND STREAMI CANAL ~/--- - Khaj,wan VILLAGE HAVING 5000 AND ABOVE POPULATION WITH NAME - URBAN AREA WITH POPULATION SIZE-CLASS I,II,IV &V .. POST AND TElEGRAPH OFFICE. PTO DEGREE COLLEGE AND TECHNICAL INSTITUTION ... ••••1Bl m BOUNDARY, STATE DISTRICT REST HOUSE, TRAVELLERS' BUNGALOW, FOREST BUNGALOW RH TB rB CB TA.HSIL AND CANAL BUNGALOW NEWLY CREATED DISTRICT YAMuNANAGAR Other villages having PTO/RH/TB/FB/CB, ~tc. are shown as .. .Damla HAS BEEN FORMED BY TRANSFERRING PTO AREA FROM :- Western Yamuna Canal W.Y.C. olsTRle T AMBAl,A I DISTRICT KURUKSHETRA SaSN upon Survt'y of India map with tn. p.rmission of theo Survt'yor Gf'nf'(al of India CENSUS OF INDIA - 1991 A - CENTRAL GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS The publications relating to Haryana bear series No. -

Gaya Travel Guide - Page 1

Gaya Travel Guide - http://www.ixigo.com/travel-guide/gaya page 1 and Nagkut Mountain. Brahmayoni offers a Max: 31.0°C Min: Rain: 8.0mm 19.20000076 sensational view of the plains. Shopaholics 2939453°C Gaya must visit the famous G B Road and May One of the most important cities in Pleasant weather. Carry Light woollen. Reaching Gaya is easy as it is well-connected India, Gaya is also known as the Max: 34.0°C Min: Rain: 20.0mm to other regions through rail, road and air. 22.60000038 land of Vishnu and Buddhism. It 1469727°C Bodhgaya is the nearest airport from where Jun serves as the second largest city of a large number of international flights for Bihar after Patna and brings a lot of Pleasant weather. Carry Light woollen, Thailand, Japan and Myanmar ply on a daily umbrella. tourism to the state. Famous For : City basis. You can also travel to Patna, which is Max: 33.0°C Min: Rain: 137.0mm around 125 km from Gaya and has direct 21.89999961 8530273°C Gaya is of great religious importance to trains for Kolkata, Delhi and Mumbai. Jul Hindus and Buddhists and is home to Pleasant weather. Carry Light woollen, numerous ancient temples and When To umbrella. archaeological sites. An amalgamation of Max: 29.5°C Min: Rain: 315.0mm 21.10000038 age-old cultures and modern lifestyle, this 1469727°C city is a must-visit for all the travellers. From VISIT Aug three sides it is surrounded by small rocky Pleasant weather. -

1959(0Nline) 2348 – 9367 (Print) an Internationally Indexed Peer Reviewed & Refereed Journal

International Research Journal of Management Science & Technology ISSN 2250 – 1959(0nline) 2348 – 9367 (Print) An Internationally Indexed Peer Reviewed & Refereed Journal Shri Param Hans Education & Research Foundation Trust www.IRJMST.com www.SPHERT.org Published by iSaRa Solutions IRJMST Vol 10 Issue 6 [Year 2019] ISSN 2250 – 1959 (0nline) 2348 – 9367 (Print) Thought of B.R.Ambedkar in the context of Indian Industrial policy Md saad Uddin (Mirza Ghalib College, Gaya, Bihar) After long periods of disregard, the thoughts of B.R. Ambedkar appear to pick up money. While his considerations on Indian culture and governmental issues have collected more consideration, a portion of his financial thoughts also merit more prominent consideration. Referred to a great extent as the dad of the Indian Constitution and a pioneer of Dalits, Ambedkar started his vocation as a financial expert, making significant commitments to the major monetary discussions of the day. He was, truth be told, among the best taught financial experts of his age in India, having earned a doctorate in financial matters from Columbia University in the US and another from the London School of Economics. Ambedkar's London doctoral postulation, later distributed as a book, was on the administration of the rupee. Around then, there was a major discussion on the overall benefits of the best quality level opposite the gold trade standard. The highest quality level alludes to a convertible cash where gold coins are given, and might be supplemented with paper cash, which is swore to be completely redeemable in gold. Conversely, under the gold trade standard, just paper cash is given, which is kept replaceable at fixed rates with gold and specialists back it up with outside money stores of such nations as are on the highest quality level. -

University Faculty Details Page on DU Web-Site

University Faculty Details Page on DU Web-site Title Prof./Dr./Mr. First Name Arjumand Last Ara Photograph /Ms. Name Designation Sr. Assistant Professor Department Urdu Address Department of Urdu, Faculty of Arts, University (Campus) of Delhi, Delhi-7 (Residence) 5/3, University Road, University of Delhi, Delhi-7 Phone No (Campus) 91-011-27666627 (Residence)optional 91-011-27666266 Mobile 9810598859 Fax Email [email protected] Web-Page Education Subject Institution Year Details Ph.D. JNU, New Delhi 2001 Thesis topic: Editing of ‘Diwan-e Bayan’ with a Comprehensive Foreword M.Phil. JNU, New Delhi 1996 Editing of Masnavi Lakht-e Jigar, by Munshi Bal Mukund Besabr M.A. JNU, New Delhi 1994 Subjects: Urdu B.A. Meerut University, U.P. 1988 Subjects: Hindi, English, Geography Career Profile Organization / Institution Designation Duration Role University of Delhi Assistant Professor Since 2006 Teaching and research in Senior Scale University of Delhi Lecturer From Teaching and research 18.11.2002- 2006 National Council for Research Assistant 1999-2002 Editing of monthly Promotion of Urdu educational and literary Language, HRD, New Delhi magazine ‘Urdu Duniya’ Research Interests / Specialization www.du.ac.in Page 1 Research interests: Translations, Progressive Literature, Feminist writing. Teaching Experience ( Subjects/Courses Taught) Post-graduate: 1. History of Urdu Literature: Poetry in Delhi in 18th Century Delhi, Progressive Movement of 20th Century 2. Poetry (Ghazal & Nazm): Quli Qutub Shah, Khwaja Mir Dard, Aatish, Ghalib, Iqbal, Firaq Gorakhpuri, Majrooh Sultanpuri, Akhtarul Iman 3. Poetry (Masnavi and Qasida): Gulzar-e Nasim by Daya Shankar Nasim, Qasida Na’tiah Madih Khairul Mursalin by Mohsin Kakorvi 4. -

Gaya Water Supply Phase 1 (GWSP1) Subproject

Initial Environmental Examination Document Stage: Draft Project Number: 41603-024 May 2017 IND: Bihar Urban Development Investment Program — Gaya Water Supply Phase 1 (GWSP1) Subproject Prepared by Urban Development and Housing Department, Government of Bihar for the Asian Development Bank. This draft initial environmental examination report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. ABBREVIATIONS ADB — Asian Development Bank BOQ — bill of quantity BPLE — Bihar Public Land Encroachment Act BSPCB — Bihar State Pollution Control Board, BUIDCo — Bihar Urban Infrastructure Development Corporation BUDIP — Bihar Urban Development Investment Program C & P — consultation and participation CBO — community-based organization CFE — Consent for Establishment CFO — Consent for Operation CGWB — Central Ground Water Board CITES Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species — of Wild Fauna and Flora CMS — Convention on Migratory Species of Wild Animals CWR — clear water reservoir DFO — Divisional Forest Officer DSC — design and supervision consultants EAC — Expert Appraisal Committee EARF — environmental assessment -

Copyright by Indulata Prasad May 2016

Copyright by Indulata Prasad May 2016 THE DISSERTATION COMMITTEE FOR INDULATA PRASAD CERTIFIES THAT THIS IS THE APPROVED VERSION OF THE FOLLOWING DISSERTATION: LAND REDISTRIBUTION AND DALIT ASSERTION: MAPPING SOCIAL CHANGE IN GAYA, BIHAR, INDIA Committee: Charles R. Hale, Supervisor Kamala Visweswaran, Co-Supervisor Sharmila Rudrappa Shannon Speed João H. Costa Vargas Maria Franklin LAND REDISTRIBUTION AND DALIT ASSERTION: MAPPING SOCIAL CHANGE IN GAYA, BIHAR BY INDULATA PRASAD, P.G.D.; M.A. DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT AUSTIN MAY 2016 DEDICATION To my parents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation marks the culmination of a long and eventful journey and I want to thank everyone who has been a part of it. My deepest gratitude to my teacher, mentor and guide, Kamala Visweswaran, who has been very supportive of my work. I thank her for her immense patience in letting me “arrive” at my key arguments, interventions and conclusion. Without her consistent help, guidance and support, this dissertation would not have been possible. I thank Sharmila Rudrappa for her encouragement throughout the research process. I greatly benefitted from her advice that helped me identify and articulate some of the key concepts and intervention of my research. I thank Charlie Hale for his unconditional support and patience, particularly, towards the end of the writing phase that was critical to finishing the dissertation in a timely manner. I thank Shannon Speed, João Vargas, for their comments and feedback on this dissertation. -

Dr. Jugnu Jahan

1. Name :- Dr. Jugnu Jahan 2. Designation :- Assistant professor 3. Department :- History 4. Qualification :- Ph.D 5. Specialization in teaching :- History 6. Full Address :- C/o Late Md. Equbal Ashraf, Gewal Bigha,Munni Masjid, Near Boli Par, Gaya Pin-823001 7. Mobile No. :- 7870300931 8. Whatsapp No :- 7033785504 9. Email Id :- [email protected] 10.Activities in Research & :- 1. Participated in National Seminar on Academic fields “Role of Bihar In India’s Constitution Making”, held on 18th ,19th & 20th Dec 2018 at M.G University Bodh Gaya, Bihar. 2. Participated in National Seminar on “Atrocities Against Women ”, held on 1st Dec 2018 at M.G University Bodh Gaya, Bihar. 3. Participated in National Seminar on “Relevance of Dr.B.R Ambedkar in 21st Century ”, held On16thMarch2019 at M.G University Bodh Gaya,Bihar. 4. Participated in International Seminar on “Promotion of Buddhist Pilgrimage and Tourism ”, held On30thJanuary2020 at Bodh Gaya,Bihar. 5. Participated in “Training of Trainers Programme on Youth Leadership & People Skills” held from 23rd Aug 2014 to 27th Aug 2014 at Navjyoti Nikentan,Patna,Bihar . 6. Published Journal on“Family is an important institution in ancient Indian society” Published from Anand Abhinandan Publication Patna Bihar, Page No-116-118,UGC Approved Journal No- 2321-3116.Year 2018. 7. Published Journal “Analysis of Structure and form of Vedic Society” Published from Deptt. Of. Philosophy & Religion faculty of Arts ,B.H.U, Varanasi Page No-211-16,UGC Approved Journal No- 141/2004. Year 2010 11. Profile:- My Self Dr.Jugnu Jahan, Assistant Prof, have joined in Mirza Ghalib College,Gaya on 13th Sept 2014 in the Depeartment of History. -

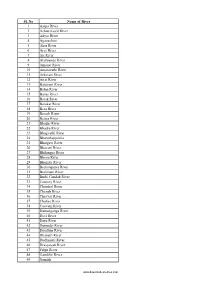

List of Rivers in India

Sl. No Name of River 1 Aarpa River 2 Achan Kovil River 3 Adyar River 4 Aganashini 5 Ahar River 6 Ajay River 7 Aji River 8 Alaknanda River 9 Amanat River 10 Amaravathi River 11 Arkavati River 12 Atrai River 13 Baitarani River 14 Balan River 15 Banas River 16 Barak River 17 Barakar River 18 Beas River 19 Berach River 20 Betwa River 21 Bhadar River 22 Bhadra River 23 Bhagirathi River 24 Bharathappuzha 25 Bhargavi River 26 Bhavani River 27 Bhilangna River 28 Bhima River 29 Bhugdoi River 30 Brahmaputra River 31 Brahmani River 32 Burhi Gandak River 33 Cauvery River 34 Chambal River 35 Chenab River 36 Cheyyar River 37 Chaliya River 38 Coovum River 39 Damanganga River 40 Devi River 41 Daya River 42 Damodar River 43 Doodhna River 44 Dhansiri River 45 Dudhimati River 46 Dravyavati River 47 Falgu River 48 Gambhir River 49 Gandak www.downloadexcelfiles.com 50 Ganges River 51 Ganges River 52 Gayathripuzha 53 Ghaggar River 54 Ghaghara River 55 Ghataprabha 56 Girija River 57 Girna River 58 Godavari River 59 Gomti River 60 Gunjavni River 61 Halali River 62 Hoogli River 63 Hindon River 64 gursuti river 65 IB River 66 Indus River 67 Indravati River 68 Indrayani River 69 Jaldhaka 70 Jhelum River 71 Jayamangali River 72 Jambhira River 73 Kabini River 74 Kadalundi River 75 Kaagini River 76 Kali River- Gujarat 77 Kali River- Karnataka 78 Kali River- Uttarakhand 79 Kali River- Uttar Pradesh 80 Kali Sindh River 81 Kaliasote River 82 Karmanasha 83 Karban River 84 Kallada River 85 Kallayi River 86 Kalpathipuzha 87 Kameng River 88 Kanhan River 89 Kamla River 90 -

F ENVIRONMENTAL CLIMATIC CHALLENGES in BIHAR 1,*Reshma Perween and 2 Mohammad Adil Hassan

ss zz Available online at http://www.journalcra.com INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF CURRENT RESEARCH International Journal of Current Research Vol. 13, Issue, 06, pp.18006-18010, June, 2021 ISSN: 0975-833X DOI: https://doi.org/10.24941/ijcr.41503.06.2021 RESEARCH ARTICLE OPEN ACCESS A STUDY OF ENVIRONMENTAL CLIMATIC CHALLENGES IN BIHAR 1,*Reshma Perween and 2 Mohammad Adil Hassan 1 2Assistant Professor, Department of Botany, Mirza Ghalib College, Gaya, Bihar, India ARTICLE INFO Senior Municipal &ABSTRACT Environmental Engineer, Town Council, Bodhgaya, Bihar, India Article History: The present research paper outlines the environmental climatic challenges in Bihar, highlighted the Received 29th March, 2021 climatic environmental issues describes the measures undertaken by Government of Bihar and Received in revised form reviews an extensive number of studies to address the environmental issues of different districts of 17th April, 2021 Bihar state. The major aim of and objective to this present dissertation of environmental issue and Accepted 24th May, 2021 challenges is to provide a sound foundation for the framework of future strategies to came out with th Published online 30 June, 2021 these environmental issues to secure clean environment for future generations. Furthermore, the Government of India has also introduced the National Rural Drinking Water Supply Program in order Key Words: to address the environmental issues in Bihar. The present dissertation highlights the potential future, Citizen Awareness, risk and justifies a comprehensive research effort directed to obtaining definitive results. Indeed, a Environmental Challenges, quick assessment, and adoption of remedial measures without delay, is imperative for the future of Drinking Water, this aquatic system. -

District Profile

Ministry of Micro, Small & Medium Enterprises Government of India DISTRICT PROFILE GAYA 2019-20 Carried out by MSME-Development Institute (Ministry of MSME, Govt. of India,) Patliputra Industrial Estate, Patna-13 Phone:- 0612-2262719, 2262208, 2263211 Fax: 06121 -2262186 e-mail: [email protected] Web- www.msmedipatna.gov.in Mahabodhi Temple, Bodhgaya Vishnupad Temple, Gaya Mangala Gauri Temple, Gaya 2 FOREWORD At the instance of the Development Commissioner, Micro, Small & Medium Enterprises, Government of India, New Delhi, District Industrial Profile containing basic information about the district of Gaya has been updated by MSME-DI, Patna under the Annual Plan 2019-20. It covers the information pertaining to the availability of resources, infrastructural support, existing status of industries, institutional support for MSMEs, etc. I am sure this District Industrial Profile would be highly beneficial for all the Stakeholders of MSMEs. It is full of academic essence and is expected to provide all kinds of relevant information about the District at a glance. This compilation aims to provide the user a comprehensive insight into the industrial scenario of the district. I would like to appreciate the relentless effort taken by Shri Ravi Kant, Assistant Director (EI) in preparing this informative District Industrial Profile right from the stage of data collection, compilation upto the final presentation. Any suggestion from the stakeholders for value addition in the report is welcome. Place: Patna Date: 31.03.2020 3 Brief Industrial Profile of Gaya District 1. General Characteristics of the District– Gaya formed a part of the district of Behar and Ramgarh till 1864. -

Government of India Ministry of Water Resources, River Development & Ganga Rejuvenation Lok Sabha Unstarred Question No

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES, RIVER DEVELOPMENT & GANGA REJUVENATION LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO. 1980 ANSWERED ON 27.07.2017 INTER-LINKING OF RIVERS 1980. SHRI ASHWINI KUMAR CHOUBEY Will the Minister of WATER RESOURCES, RIVER DEVELOPMENT AND GANGA REJUVENATION be pleased to state: (a) the current status of the interlinking of rivers project; (b) whether the Government plans to merge Phalgu river situated in Gaya district of Bihar with Ganga river; and (c) if so, the details thereof along with the timeframe of the same? ANSWER THE MINISTER OF STATE FOR WATER RESOURCES, RIVER DEVELOPMENT AND GANGA REJUVENATION (DR. SANJEEV KUMAR BALYAN) (a) Under the National Perspective Plan (NPP) for water resources development through inter basin transfer of water prepared by this Ministry, National Water Development Agency (NWDA) has identified 30 links (16 under Peninsular Component & 14 under Himalayan Component) for preparation of Feasibility Reports (FRs). After survey and investigations, FRs of 14 links under Peninsular Component and 2 links in the Himalayan component have been prepared. Present status, States concerned and States benefited of Inter Basin Water Transfer Links are given in Annexure. Based on the concurrence of concerned states four priority links for preparation of Detailed Project Reports (DPRs) have been identified viz; Ken-Betwa link project Phase-I & II, Damanganga- Pinjal link, Par-Tapi-Narmada link and Mahanadi-Godavari link. The DPRs of Ken-Betwa Phase I & II, Daman-Ganga-Pinjal, Par-Tapi-Narmada have been prepared and shared with the respective States. Further, various Statutory Clearances have been obtained for KBLP Phase-I. -

District Wise Activities That Can Be Taken up for Rejuvenation of Rivers with Focus for Support for Migrant Workers Returning Home

District wise activities that can be taken up for Rejuvenation of Rivers with focus for support for migrant workers returning home Various works and activities involved in rejuvenation of small river in Ganga basin which are tributaries of River Ganga can be taken up under MGNREGA for generation of employment for migrant workers returning home. Accordingly, a total of 68 districts located in Ganga basin have been identified and small rivers and tributaries of River Ganga/ its tributaries have been shortlisted. Rejuvenation of these small tributaries forms an important component of rejuvenating River Ganga. Various activities have also been identified which can be implemented during pre-monsoon periods in the catchment of these rivers which will also help in rejuvenating these rivers. The potential areas for works programs to provide employment opportunities to them can be through MGNREGA, CAMPA & other funds for small river rejuvenation and afforestation. The components of work for small river rejuvenation may include desilting, construction of clean dam & other structures for water harvesting & storage, afforestation in the catchment, protection work for water bodies. The list of these activities have also been identified and given in the enclosed statement. The list of activities are not exhaustive but is illustrative as applicable for concept. These activities are such that they may not involve highly skilled manpower for their implementation. Even unskilled or semi-skilled manpower can be utilized for their implementation. Out of 73 districts, 34 districts (S No 1 to 34) fall in Uttar Pradesh while 20 are in Bihar (S No 35 to 54). Similarly, 5 in Jharkhand (S No 55 to 59), 12 districts are located in Madhya Pradesh (S No 60 to 71), and 2 in Rajasthan (S No 72-73).